Every day, reports about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine mention drone strikes, both inside and outside the battlefield. It seems (to me at least) that their use by Kyiv has even led to a change in the perception of the technology. Military drones used to be associated with the idea of an unjust war. In the framework of this invasion, however, they appear as high-tech guerrilla tools that disrupt imperialism and allow civilians and soldiers to defend their country.

In this context, the book Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest, edited by Sarah Tuck and Louise Wolthers, invites readers to reassess the ambiguous role, visibility and significance that drone technology plays in artistic and political praxis.

In this context, the book Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest, edited by Sarah Tuck and Louise Wolthers, invites readers to reassess the ambiguous role, visibility and significance that drone technology plays in artistic and political praxis.

Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest is based on a two-year research project between 3 major cultural institutions in Pakistan , Sweden and Cyprus. The publication accompanies the exhibitions and round tables related to critical engagement with drone technologies. The research, both curatorial and artist-led, investigates the impacts that drones have on our understanding of operations of warfare, surveillance and protest, and the ways in which seeing at a distance without being seen disrupts geographies of proximity, distance and visibility.

The exhibition ‘Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest’ opened across three cultural institutions located in Nicosia in Cyprus, Lahore in Pakistan and Gothenburg in Sweden. The geopolitical context of each city called for a different perspective on drone technologies.

In Lahore, the exhibition focused on artists who themselves had been under the surveillance of a drone and had personally experienced the violence and consequences of drone warfare. Their work reflects the horror that American drone strikes cause because of the number of civilian casualties and the fact that the strikes became the justification for terrorist bombing.

Ran Slavin, Battlefields, 2018

Ran Slavin, Battlefields (excerpt), 2018

Ran Slavin, Battlefields, 2018

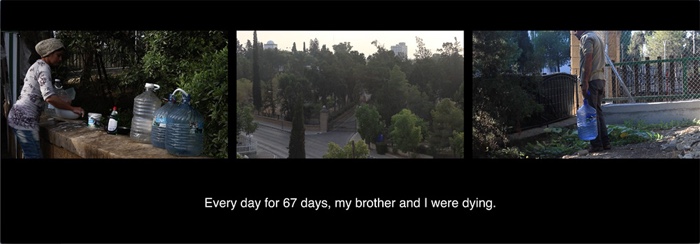

Efi Savvides, Judgement Day (video stills), 2018

In Nicosia, a city divided in two on an island where relics of war and British colonisation abound, the artists looked at the infrastructures of surveillance and control.

In Gothenburg, the artists explored how Sweden, a country with a peace-loving image, is implicated in the production of violence. Their works bring drone war ‘home’ by shedding light on refugee camps in Sweden, the Swedish military industry, as well as the exploitation of the Sámi people.

Stelios Kallinikou, Parachuters. Over The Horizon, 2018

The book includes many texts by artists, curators, thinkers and art critics. Many of them comment on the exhibitions which makes for quite a few repetitions. The standout essay for me was Sehr Jalil‘s text in which she explains how pigeons have been used as “living drones.” The birds were trained to be diligent spies for the CIA in the Soviet Union or for the British in WW2. Ravens were even used during the Cold War to drop bugging devices on window sills. Recent stories even report on pigeons being held in custody in Pakistan and India on charges of spying.

The three exhibitions were preceded by a series of roundtables that hosted debates on the ethics, verticality, politics of control and the adoption of drones as a tool of protest and counter-surveillance. The transcript of the debates were, for me, the most interesting part of the book.

The question of vocabulary was raised several times during the discussions. Either illuminating how terms are being used to “sanitise” the use of lethal machines (in Western sources, the strikes of armed drones are ‘surgical’, ‘precise’ or ‘virtuous’ which give an aura of efficiency and even caring) or revealing words and expressions I had never heard of. The “soda straw perspective”, for example, renders the drone operator’s pinpointed point of view. They see the world through a soda straw and lack the broader perspective of what’s happening which leads to errors when shooting. Tomas van Houtryve made the problem obvious to all when commenting on his photographic series Blue Sky Days. When seeing one of his photos showing yoga classes in a park in San Francisco, many people believe that what they are seeing is people doing a Muslim prayer. Stephen Graham also explains the emergence of “subterranean insurgencies” in Gaza and elsewhere to escape the intensification of vertical scrutiny facilitated by satellites, drones and other surveillance technologies.

Another important theme that emerged several times throughout the pages was the ongoing normalisation of drone technologies and the decision-making when it comes to killing people.

Stephen Graham explained how the drone lobby group he has studied as part of his academic research “were very aware that the drone has ‘something of an image problem’. Understatement. They were saying we need to civilianise them, make them friendly, make them brightly coloured and obviously domesticate them in things like environmental hazards and disaster response and Amazon deliveries.”

The third preoccupation that kept surfacing in the book is the difficulty for communities victim of drone strikes and surveillance to communicate their suffering to those of us who live in Europe and elsewhere. How can they generate empathy? Focusing on connections between individuals, between communities and between bodies might offer one solution to the problem. People are rarely killed alone. Drone operators tend to shoot when they see gatherings of people such as weddings, funerals and other celebrations. It might be easier for Western audiences to relate to strangers’ death when they perceive that the violence affects whole families.

Debates about the ethics and politics of drones have lost some of their prominence in art exhibitions and publications. I’m glad that Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest reminds us of the necessity to maintain robust and nuanced conversations about a technology that keeps killing civilians across the world today.

Here are some of the artworks presented in the book:

Stelios Kallinikou, View 5. Over The Horizon, 2018

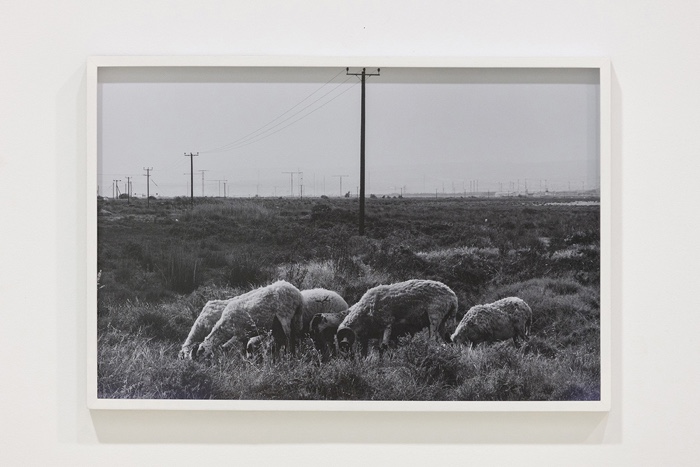

Stelios Kallinikou, Sheep, 2018. Over the Horizon

In Over the Horizon, Stelios Kallinikou dives into the pieces of British colonial heritage that dot the Cypriot landscape. On the small Mediterranean island, HAARP, British sovereign bases, guarded British military base, wide-field telescope of the British National Space Centre, gigantic British radio-listening communication antennae and other surveillance infrastructure coexist with diverse cultural, historical, geographic and natural elements.

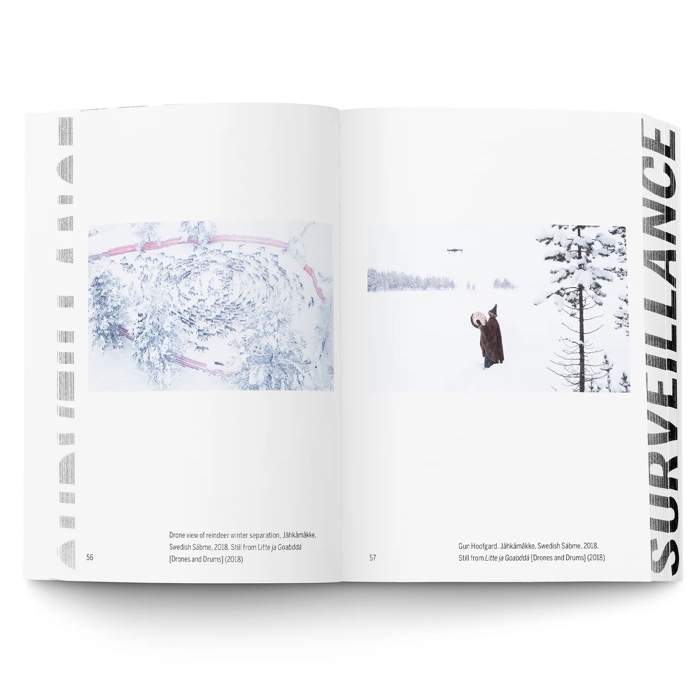

Ignacio Acosta, still from Litte ja Goabddá [Drones and Drums], Jåhkåmåhkke [Jokkmokk], Norrbotten, Swedish Sábme, 2018

Litte ja Goabddá [Drones and Drums] resists the vertical, top-down, military control associated with drone technologies. In the hands of Sami communities, who are resisting pacifically against deforestation and extractive industries, the drone’s capacity to generate accurate image-based mapping and analytics, the done is associated with a traditional drum to monitor the activities of the mining industry but also to reconcile the technological and the spiritual in the counter-protest against settler colonialism.

Mhairi Sutherland, Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest. Installation view Topographical Evidence. Photograph Cecilia Sandblom

Mhairi Sutherland, Drone Vision: Warfare, Surveillance, Protest. Detail Escalate, 2018t.

Mhairi Sutherland undertook an investigation into the industrial activity of Saab. Saab, known to most of us as a car manufacturer, also produces new fighter jets involved in the global arms trade.

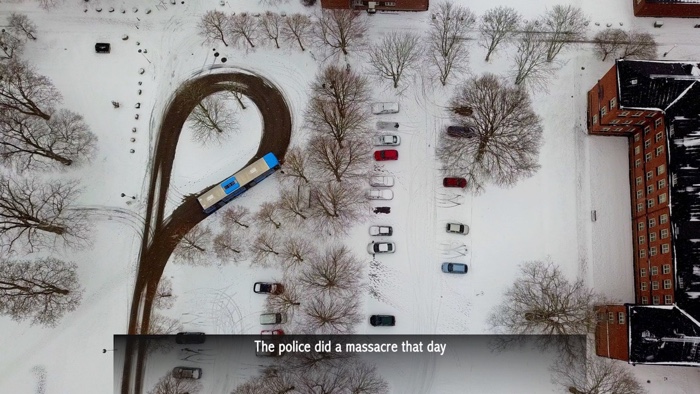

Behjat Omer Abdulla, It’s Your Turn, Doctor (film still), 2018

Behjat Omer Abdulla, It’s Your Turn, Doctor, 2018

Behjat Omer Abdulla’s work combines a series of drawings and a video. The drawings are based on stills from youtube footage that record the immediate aftermath of an aerial bombing on May 24, 2013, on the city of Daraa in Syria and the rescue of Mohammed Al Maani from the rubble. As for the film, a drone flies above the ‘asylum reception centre’ at Restad Gård, about 60 kilometres north of Gothenburg.

Taken together, the artworks connect, on the one hand, the violence that leaves people homeless, stateless and forced to plead for their rights to exist in a foreign country they have risked their lives trying to reach and, on the other hand, our inability to fully comprehend and thus empathise with what they have endured.

“There was a very interesting moment in Behjat Omer Abdulla’s project”, Daniel Jewesbury explains in an essay that comments on the work. “The artist was concerned about using a commercial drone in the context of Restad Gärd, where many of the residents have PTSD from the consequences of drone war and violence. Despite the sonic difference between a military and a commercial drone the artist was mindful about the use of drones but was reassured when some of the residents explained how commercial drones had been used to map safe routes out of danger. So while the view from above has historically been aligned to an imperial gaze, the use of commercial drones has co-opted this sightline as a part of protest against imperialism and colonisation.”

Book spreads:

Related books: The Drone Chronicles 2001-2016, Sudden Justice: America’s Secret Drone Wars, Book review: Drone. Remote Control Warfare, Book review: A Theory of the Drone.

Related stories: The Living Dead – How drones and AI could help “the loneliest plant in the world”, Tales from the Crust. Portraits of extractive violence and resistance, Tanks, drones, rockets and other sound machines. An interview with Nik Nowak, Drones with Desires. A machine with inbuilt human memories, Eyes from a distance. Personal encounters with military drones, A screaming comes across the sky. Drones, mass surveillance and invisible wars, The Grey Zone. On the (il)legitimacy of targeted killing by drones, Tracking Drones, Reporting Lives, Drones, pirates, everyday racism. An interview with graphic designer Ruben Pater, Under the Shadow of the Drone, A dystopian performance for drones, KGB, CIA black sites and drone performance. This must be an exhibition by Suzanne Treister, The Digital Now – ‘Drones / Birds: Princes of Ubiquity’, etc.