Notes about A screaming comes across the sky. Drones, mass surveillance and invisible wars , Laboral’s new exhibition that addresses the ethical and legal ambiguity of drones, mass surveillance and war at a distance.

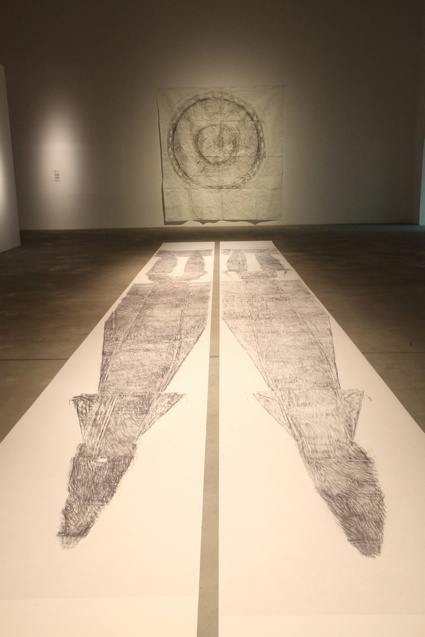

Hito Steyerl, Strike

Hito Steyerl, Strike

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers. Creech AFB, Nevada, 21.6.2011

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers. Creech AFB, Nevada, 21.6.2011

Drones are very much part of today’s culture. You can buy one on amazon and fly it as if it were a sophisticated kite. You also probably read how they are (or will be) used to deliver urgent medical supplies, shoot movies, monitor crops, track wildlife or gather information after a natural or manmade disaster.

In many people’s minds, hobbyist and civilian uses of UAVs have overtaken the military role and origins of drones. No surprise here as what governments are doing with drones, who they are killing and how is a mystery for the public. And even often for government officials, as this video shown by curator Juha van’ t Zelfde during Laboral’s drone conference illustrates:

Last Week Tonight with John Oliver: Drones

Drones have been operating and killing since the early 2000s. Yet, we still have fairly few or no statistics regarding civilian casualties. The Bureau of Investigative Journalist does a great job at counting strikes and casualties in Yemen, Somalia and Pakistan. Data gets blurry when it comes to attacks in other countries such as Afghanistan. And a lack of transparency goes hand in hand with a lack of accountability. The wars are fought in remote countries by invisible technologies operated in the name of people who have only a very limited knowledge of what is happening ‘on the war front’ and this situation contrasts with the ability that satellite images have given us to see and explore the world. The irony is illustrated by James Bridle’s ongoing series of aerial photographs of military surveillance drones, found via online maps accessible to everyone.

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers. Dryden Research Center California, 2011

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers. Dryden Research Center California, 2011

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers

James Bridle, Watching the Watchers

The title A screaming comes across the sky is taken from Thomas Pynchon’s novel, Gravity’s Rainbow, which explores the social and political context behind the development of the V-2 rocket, the first long-range ballistic missile and the first man-made object to enter the fringes of space. The rocket was developed by the German military during World War II to attack Allied cities as a form of retaliation for the ever-increasing Allied bombings against German cities. Today’s technologies of war, such as the MQ-1 Predator and MQ-9 Reaper drones, and their laser-guided Hellfire missiles, bear resemblance to the V-2 in their ability to operate unseen and to strike without warning.

In the post-PRISM age of mass surveillance and invisible war, artists, alongside journalists, whistleblowers and activists, reveal the technological infrastructures that enable events like drone-strikes to occur.

I’ve now seen quite a few exhibitions that explored the politics, ethics and meanings of drones. A screaming comes across the sky manages to bring a fresh and compelling perspective on the issue by taking sometimes a more oblique, metaphorical approach to drones. While the curator selected some of the most iconic works dealing directly with drones today, he also looked at artists who are interested in questions of surveillance and control but in a rather poetical, symbolic or even sometimes humourous way.

Martha Rosler, Theater of Drones

Martha Rosler, Theater of Drones

Martha Rosler, Theater of Drones, 2013

Martha Rosler, Theater of Drones, 2013

Martha Rosler’s Theater of Drones is a great introduction to the subject of drone warfare. The banner installation was first exhibited in Charlottesville, the first city in the United States to pass a law restricting the use of drones in its airspace

Talking about the drones, Rosler said: “They appear to make war invisible, but of course in the countries that we’re bombing, and where people are being killed, they are a terror fact of everyday life. They don’t terrorize us, because we have this classic split, which we also had during the Vietnam War of over here and over there are two different worlds, and they’re not really connected.”

The banners list a series of chilling facts about drones: “The Air Force has plotted the drone future to 2047. The Pentagon plans to increase funding by 700% over the next decade.” “Since 2004, drone strikes have killed an estimated 3,115 people in Pakistan. Fewer than 2 percent of the victims are high-profile targets. The rest are civilians, and alleged combatants. ” And this little gem of a quote by a Pentagon official:

“They don’t get hungry. They’re not afraid. They don’t forget their orders. They don’t care if the guy next to them has just been shot. Will they do a better job than humans? Yes.”

The same room also showed works developed by fabLAB Asturias. The prototypes, platforms and maps bring the drone issue into a context closer to citizens’ daily interests and experiences (a dedicated post about fabLAB’s drone experiments is coming up!) Their projects also remind the public that the U.S> military doesn’t have the monopoly of questionable use of drones. Using them for surveillance, border control and in military contexts is very much part of the European agenda as well.

Quick tour of the other works on show:

Lot Amoros, Dronism, 2013

Lot Amoros, Dronism, 2013

Lot Amoros, Dronism, 2013

Lot Amoros, Dronism, 2013

Lot Amoros, Dronism, whitedesert

Lot Amoros, Dronism, whitedesert

As part of his ongoing research on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), Lot Amoros placed posters around Egypt to inform people how to protect themselves from Israel’s Heron drones. Israel is the world’s leading exporter of military drones. As this video shows, Israeli drones and other weapons meet with great success on the international market as they have been repeatedly tried and tested on Palestinians.

The instructions of the Dronism document were directly quoted from real Al-Qaida drone documents. All al-Qaida references or aggressive languages were removed and replaced with peaceful instructions for the sole purpose of offering innocent civilians a series of tools to protect themselves from unmanned aerial vehicles, using common materials and trash to construct frequency inhibitors, camera blinders, etc.

Amoros also intended to send the instructions to Palestine on board a tiny DIY drone. It turned out that flying the quadcopter over the border into Palestinian territory was too dangerous. The artist and activist did however succeed to send the instructions via underground tunnels.

Laurent Grasso, On Air (still)

Laurent Grasso, On Air (still)

I was so glad to get another chance to see Grasso’s wonderful On Air again. , The film, shot in 2009 in The United Arab Emirates, looks at traditional hawk hunting. The bird in the movie is equipped with light and sophisticated surveillance equipment. Once let to roam free above the land, it becomes a spying tool, recording every dune and village it flies over. The images are fascinating but they are also threatening.

The movie and its paranoia-inducing music reminds us that a technique to use pigeons for aerial photography of enemy lines during wars was developed as early as 1907. The practice might not have vanished completely. A few years ago, articles reported that Iranian security forces had captured a pair of “spy pigeons,” not far from one of the country’s nuclear processing plants.

Alicia Framis, History of Drones

Alicia Framis, History of Drones

Alicia Framis, Pigeon photographers

Alicia Framis, Pigeon photographers

Which brings us nicely to Alicia Framis’s History of Drones. Her taxidermied work presents the pigeon as the predecessor of today’s drones. In 1908, German apothecary Julius Neubronner patented aerial photography by means of a pigeon photographer. The invention was tried out for military air surveillance in the First World War and later.

Besides actually being used in military contexts as a means of surveillance and collecting intelligence, they were indeed unmanned aerial instruments, which might had a different historical importance if it wasn’t for the quick and strong progress in the field of aviation. In this new work, Framis creates a light-hearted reminder of the evolution of aerial espionage.

Preparing James Bridle’s Drone Shadow drawing in Gijón, 2014

Preparing James Bridle’s Drone Shadow drawing in Gijón, 2014

James Bridle, Drone Shadow drawing in Gijón, 2014

James Bridle, Drone Shadow drawing in Gijón, 2014

MQ1 Predator Drone Shadow

located in the port of Gijón. The work has been painted by local practitioners using James Bridle’s: Drone Shadow Handbook, which can be found here. A brilliantly simple and poignant reminder of military technologies, as James Bridle reminds us: “We all live under the shadow of the drone, although most of us are lucky enough not to live under its direct fire.”

Check out the video below for more details about Bridle’s interest in drones:

The talk is available in spanish as well.

Marielle Neudecker, The Air Itself is One Vast Library

Marielle Neudecker, The Air Itself is One Vast Library

Really like this work. I wrote about it Here.

Roger Hiorns, Untitled (view of the exhibition)

Roger Hiorns, Untitled (view of the exhibition)

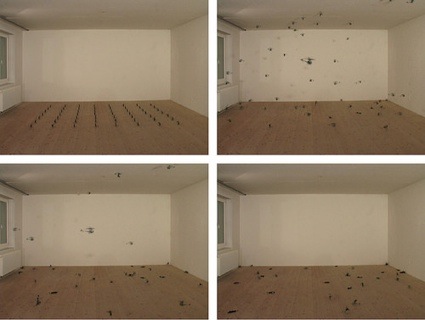

Roman Signer, 56 kleine Helikopter, 2008

Roman Signer, 56 kleine Helikopter, 2008

A video showing 56 remote-controlled toy helicopters taking to the sky to great chaos.

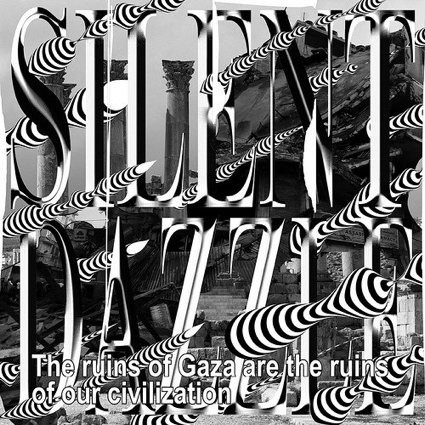

Metahaven, Silent Dazzle, 2014

Metahaven, Silent Dazzle, 2014

Metahaven, Silent Dazzle

Metahaven, Silent Dazzle

Hito Steyerl, Strike

Hito Steyerl, Strike

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

AeraCoop (Lot Amorós, Cristina Navarro y Alexandre Oliver), Flone

A screaming comes across the sky. Drones, mass surveillance and invisible wars is at LABoral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial (Art and Industrial Creation Centre) until 12 April 2015. In collaboration with Lighthouse.

Related stories: Flone, The Flying Phone, A dystopian performance for drones, KGB, CIA black sites and drone performance. This must be an exhibition by Suzanne Treister, Under the Shadow of the Drone and The Digital Now – ‘Drones / Birds: Princes of Ubiquity’.