In this age of mass extinction, a growing number of animal and plant species can no longer be found in the wild. They survive exclusively under human care, far away from their original habitat. Encephalartos woodii, Wood’s cycad is one of them. Encephalartos woodii is not only one of the rarest plants in the world, it has also been called the loneliest plant in the world.

You can find it in botanic gardens and cycad collections throughout the world. Each and every one of the specimens, however, is a clone of a single male specimen found in 1895 in the Ngoye Forest, South Africa. The cycad was removed from the wild and its offsets have since been propagated worldwide. Because both sexes are needed for reproduction, botanists have gone on several expeditions specifically looking for a female specimen. So far, with no success. Without it, the cycad is condemned to continued assisted reproduction and survival on the edge of extinction.

C-Lab, Living Dead: On the Trail of the Female, 2022

The Ngoye Forest is vast and most of it is difficult to access. In the hope that a female is growing in areas that have not been inspected yet, artist and researcher Laura Cinti from C-Lab has been working on a project that uses a drone to map and survey unexplored part of the forest where a specimen of the elusive female cycad might be growing.

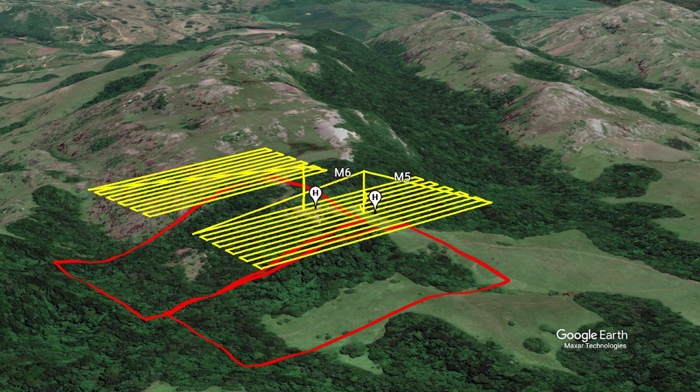

Called Living Dead: On the Trail of a Female, the project used a drone equipped with a multispectral camera and programmed to fly in a grid over two selected areas each around 40 acres collecting a total of 4000 images. Flying 80 metres above the otherwise inaccessible parts of the Ngoye Forest, the drone captured images with a ground resolution of 8 and a half cm. The mission was conducted by Dr Debbie Jewitt of Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife that manages the Ngoye Forest and 120 other protected areas.

The drone missions and aerial flights provided a wealth of photos that were stitched together to form a map that could be analysed.

I talked with the artist about the drone research and about AI in the Sky, the follow-up project that aims to expand the exploration and use machine learning analysis together with synthetic data to improve how the maps are searched.

Dr Laura Cintiis a research-based artist working with biology, co-founder and co-director, together with Howard Boland, of C-LAB – a transdisciplinary bio art collective and organisation.

Two of the remaining stems of Encephalartos woodii at Ongoye Forest. The smaller one on the right is presumably the one which was collected in 1916 to be moved to Pretoria, early 1900’s (photo)

Two of the remaining stems of Encephalartos woodii at Ongoye Forest. The smaller one on the right is presumably the one which was collected in 1916 to be moved to Pretoria, early 1900’s (photo)

Hi Laura! How did you find out about the Encephalartos woodii and what made you want to work with that plant in particular?

I came across the story of the Encephalartos woodii whilst doing research on our current biodiversity crisis focusing on plants. What captivated me was how it acts as a poignant reminder of just how easily we can lose species and it highlights the relationship between human intervention and the survival of plant life. The story illustrates how its inability to survive in the wild is linked to its isolation from the ecosystems it relies on and its confinement in human-made habitats for its protection.

I was able to develop the project (The Living Dead – On the Trail of a Female) after a successful response to the European-funded initiative Roots & Seeds XXI Biodiversity Crisis and Plant Resistance. The initiative consisted of five organisations across Europe – Ars Electronica (AT) Leonardo / Olats (FR), Universitat de Barcelona (ES) in collaboration with Institut Botànic de Barcelona – IBB (ES) and Quo Artis (ES) as lead partner, with the overall aim to generate projects that reflect on the biodiversity emergency and to raise awareness about these issues.

What inspired me with the extinct-in-the-wild male cycad – E. woodii, was how it reflects our biodiversity crisis by bringing us face to face with the experience of species loss while at the same time carrying a romantic hope of finding a female. This hope has been central to developing the work and has taken me on a journey through research archives, journals and diaries but more importantly into a physical search in a dense forest near the southern tip of Africa.

The only known single male was discovered in 1895 in the Ngoye Forest of Kwa-Zulu-Natal in South Africa. It was feared that this plant would be destroyed so stems were removed and propagated in botanical gardens. The final damaged stem of the original plant was removed in 1916 by the Forestry Department rendering the tree extinct-in-the-wild. All existing specimens are clones of this plant and, like the last wild specimen, all are male.

E. Woodii and Laura Cinti, Temperate House, Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, September 2021. Photo: Howard Boland. The E. Woodii in Kew Gardens is an offset of the only plant of this specimen ever found in the wild. It was sent to Kew in 1899

As each individual plant is either female or male, they produce cones – the female cones being wider and more egg-shaped while male cones are generally longer and more narrow – and the pollen travels from the male plant to the female via insects. Cloning is currently the only way the species survives as a “true species” and since both sexes are needed for reproduction, without a female, the E. woodii may never naturally reproduce again.

Male cone of Encephalartos woodii. Photo by Maurice Levin, 2008

The story of the Encephalartos woodii made me think of Remembering Sudan, a documentary about the last known male northern white rhino. I couldn’t watch the film till the end because it was heartbreaking and because, in general, I care so much about animals. I can’t say that I don’t care about plants of course but it is harder to empathise or to understand the tragedy of what you call the loneliest plant on Earth. What are we missing when we overlook the loss of a plant species? Is there a way to make us care more for their fate when they have no obvious and direct interest for us (like being edible and delicious for example)?

That is an important question and for most of us, it is probably right to say plants don’t generate the same level of empathy as endangered animals. I spent much of my PhD arguing how this really comes down to a human issue in terms of how we read the world and something that is problematic as we try to take on a custodian role in our environment.

Display of Encephalartos woodii at Kirstenbosch. Photo by Melanie Boehi

Cycads are fascinating, they are the oldest surviving seed plant that once covered the planet and they also appeared before the age of dinosaurs around 300 million years ago. They have changed very little since the Jurassic Era/Age of Dinosaurs and that is the reason why they are often referred to as ‘living fossils’.

Today, however, it is cycads (and not rhinos) that are the most endangered living organisms on Earth. They are threatened with extinction and a huge part of this is the impact of poaching as they are worth millions of dollars annually in illegal plant trade. To put it in perspective, some individual specimens are selling for hundreds of thousands to millions of pounds each – a contrast compared to the black rhino horn which usually goes for around £70,000. Cycads are seen as status symbols worldwide. South Africa, being the hotspot for cycad diversity, has a devastating issue with cycads being dug up from the wild by poachers and even botanical gardens are targeted. The rarer the specimens, the more sought after and that’s why the most valuable cycad -the E.woodii – in Kirstenbosch Botanical Garden (South Africa) is secured inside a cage to prevent poachers from digging it up. Rare cycads, especially E.woodii that are extinct-in-the-wild, are very appealing to collectors. Perhaps, because of their sheer rarity and being prehistoric they are sometimes seen as the equivalent of a botanical version of a dinosaur.

The project, in its search for a female partner for the lonely male, attempts to make an empathic plea and raise awareness of the devastating impact on the conservation and challenges facing these plants.

What impresses me the most about Living Dead is that it is mindful, meaningful and caring but it is also a very ambitious project with, potentially, real and important outcomes. How did you build up the alliances and collaborations with institutional actors in several European countries and in South Africa?

I spent a significant amount of time reaching out and researching. This ranged from getting in touch with botanical gardens that either have or used to have E.woodii specimens in their collection and enquiring about conservation strategies for E.woodii, researching scientific papers, accessing historical archives and lengthy correspondences with relevant experts worldwide, and also speaking to those who in the past had been on expeditions in search of the female. It revealed a diverse set of conservation approaches – such as hopes of creating a female through induced sex change and hybridisations with closely related species.

My approach was focused on how we could use remote sensing technologies to search for the female. While sourcing papers where remote sensing technologies had been specifically used in cycad identification, I came across an interview with Dr Debbie Jewitt who expressed an interest in using drones to count threatened species, mentioning cycads as one example. Jumping on this opportunity of using drones as a visual search and mapping tool I immediately got in touch, which was the seed for our collaboration. Debbie is a conservation scientist and drone pilot for Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, a governmental organisation that manages both the Ngoye Forest Reserve and 120 other protected areas in KwaZulu-Natal.

To conduct the drone search, the project was officially registered as a research project with the Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, flight permits and other important paperwork as the we were flying over protected areas. An application was also put forward for a manned flight with The Bateleurs, a non-governmental organisation who provide aerial support services to environmental missions in South Africa. One of the pilots, Steve McCurrach, offered to fly over the Ngoye Forest. This initial aerial search provided a view of the forest from above and it allowed us to assess the viability of future missions and define search areas for drone flights.

Aerial photograph over Ngoye Forest. Photo: Steve McCurrach, The Bateleurs, 2021

How easy or difficult is it to get your hands on a Encephalartos woodii clone? On the one hand, i imagine that clones of an almost disappeared species might be valuable. On the other hand, it is “just” clones…. Can anyone clone the plant and grow it in their garden?

Not quite! E. Woodii can only be propagated by tissue samples (i.e. offsets) – all originating from this one single plant found in the wild. Seeds cannot be produced because no female plant is known to exist and being extinct-in-the-wild, the clones survive in cultivation in botanical gardens (or private collections). And, with their genetic diversity being zero – they are highly sought after!

As E. woodii is protected by law – a permit is needed to move, purchase, sell, donate, receive, cultivate and own them. Artificially cultivated Encephalartos plants, pieces of a plant, cone or even pollen being carried over an international border requires a specialised permit issued by the authority of the exporting country, and an import permit issued by the authority of the importing country. While South Africa has some of the world’s strictest cycad legislation, these plants are still under threat from illegal collection where they are seized in an unidentifiable condition (i.e. misdeclaring them as palm trees which are not protected).

Living Dead uses remote sensing technologies to access previously inaccessible parts of the Ngoye Forest. How can the use of multispectral capturing help identify the presence of the plant among a multitude of other plants. Could you explain how it works?

The multispectral camera, in addition to the standard red, green, blue colour sensors, has two additional bands it collects information from: Red edge and Near InfraRed. The sensor measures the light reflected in five different bands – more bands equals more sensitivity which increases the potential for picking up variations in vegetal conditions. These bands are very useful for vegetation studies and are often used in the agricultural sector.

Every plant has its own unique spectral signature (the radiation reflected as a function of the wavelength) and it is hoped that multispectral imaging can be used to more easily spot a cycad in the forest.

For the search missions that took place, the drone was equipped with a multispectral sensor and each time the sensor was triggered, it took 5 photos of the same scene and each of them at a particular wavelength band – so one band of blue, green, red (these bands are visible to us), Red edge and Near InfraRed (these bands are invisible us).

Each band is good at distinguishing different features. For example: the blue band is good for deep water imaging, smoke plumes, atmospheric haze, clouds, snow and rock. The green band can show plant vigour and discriminate plant material. The red band can distinguish geological features or chlorophyll absorption, the Red-edge is used for plant health and age status and Near Infrared can be used for biomass content or separating water and vegetation. So, one can choose different band combinations depending on the type of feature one would like to identify. The individual bands are typically shown in grey scale, however, they can be combined in software packages and assigned a colour ramp to visualise the information they contain.

False Colour 431 (Photosynthesis and Biomass): Drone Mission Search for Encephalartos Woodii, Ngoye Forest, South Africa. Mosaic map: Dr Debbie Jewitt, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, 2022

When applying false colours using the Red edge band, photosynthesising vegetation can be seen and it also provides information about dying vegetation. For example, in the above image, we can see a blue tree. It is blue because it has died and the bare branches are showing through.

False Colour 523 – bare areas, geology types, discriminating plant material: Drone Mission Search for Encephalartos Woodii, Ngoye Forest, South Africa. Mosaic map: Dr Debbie Jewitt, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife, 2022

In the image above, the colour composite allows us to see the different geological bands running through the rocks and we can clearly see the unique spectral signatures of the different tree species. If we were to use machine learning and AI, we would train a computer to automatically identify different tree species and count them. Instead of doing it manually and to speed up the search process, we are also particularly interested in using tree shape detection and here the future proposal would be to use synthetic data as this data actually doesn’t exist.

Drone Mission Search for Encephalartos Woodii, Matrice 210 in flight over Ngoye Forest, South Africa. Photo: Dr Debbie Jewitt, Ezemvelo KZN Wildlife

Have you already done surveys in the forests and what have you learned from them?

Yes, the images above are from the surveys of the forest that we did for the search.

Larger tracks of the forest were covered using aerial imagery taken from a manned aircraft (Cessna 182) by using two camera operators: one east and the other west facing. The drone missions were conducted over several days using a DJI Matrice 210 drone equipped with a Micasense RedEdge-MX multispectral sensor in February 2022. The drone captured over 4000 images covering an area of 80 acres.

Two areas of the forest were surveyed – see image below, labelled M5 and M6. We covered a small portion of the forest – less than 1% with the drone search. While this may sound daunting, it also makes me feel hopeful as there may be an E.woodii out there.

Drone Mission Search for Encephalartos woodii: Drone flight paths of the two areas of the forest that were surveyed. Image: Howard Boland / Google Earth.

Although an E. woodii was not located during these missions, we did learn that these methods we used showed the potential of using drone technology to locate rare and endangered species and it also provided helpful information on how we could enhance and streamline the search.

I’d like to address the premise of AI in the Sky, your most recent project. The work “merges generative AI with sustainability to address the critical issue of biodiversity loss.” As I’m sure you know, vast quantities of energy and water are required to train the complex programs and models of AI. And, yet, as your project clearly demonstrates, AI can play a crucial role in the fight against deforestation, climate disruption, biodiversity loss, etc. How do you balance your concern for the environment and the use of a technology which development comes at a cost for the environment?

Good question! The balancing act between the environmental impact of AI and its potential benefits is a tricky one generally – in that it simultaneously has the ability to benefit and damage the environment. I am not sure I am yet in a position to answer this question adequately as AI in the Sky is a work in progress and one of its core aims is to open discourses around the critical issue of biodiversity loss and technology’s role in environmental conservation. AI and drones are two rapidly evolving technologies and also the most promising in terms of their abilities to enhance wildlife conservation. I think we are already seeing the benefits of machine learning and AI in other aspects of the climate crisis such as in climate predictions, agriculture, transportation and energy management.

Thanks Laura!

Both Living Dead and AI in the SKY were developed in collaboration with Conservation Scientist and Drone Pilot Debbie Jewitt and with researcher and artist Howard Boland. AI in the SKY is the winner of COAL’s NOVA_XX mention. The work will be exhibited at the NOVA_XX 2023 International Biennial (Dec 2023 – Feb 2024) at the Centre Wallonie Bruxelles in Paris. Founded in 2017, NOVA_XX is an international biennial dedicated to artistic, scientific and technological entanglement in a feminine and non-binary mode and in the 4.0 era.