A review of Art and Creativity in an Era of Ecocide. Embodiment, Performance and Practice, edited by lecturer in Human Geography Anna Pigott, Professor of Environmental Humanities Owain Jones and Reader in Art, Environment and Social Practice Ben Parry. Published by Bloomsbury.

The book uses the term ecocide in its ecological and in its broader cultural senses. It not only covers the decimation of biological complexity but also alludes to Félix Guattari’s 3 ecologies which include not only the eradication of biodiversity but also the eradication of difference, alterity and creativity at the collective and individual levels.

The book uses the term ecocide in its ecological and in its broader cultural senses. It not only covers the decimation of biological complexity but also alludes to Félix Guattari’s 3 ecologies which include not only the eradication of biodiversity but also the eradication of difference, alterity and creativity at the collective and individual levels.

As the editors acknowledge, the book collects essays from people enjoying relatively privileged positions and living in fairly rich parts of the world. But even though their texts do not reflect the full spectrum of human and non-human experiences, they cast a very critical glance at western modernity and its legacy of colonial-capitalism.

Art and Creativity in an Era of Ecocide looks at the emergence of diverse forms of artistic practice and subjectivities that respond to environmental destruction and guide us towards a more considerate, multi-species world view. The contributors ask questions such as:

How are artists and creative practitioners rethinking art and creativity when life on Earth is being slowly suffocated? How do they reinvent methods, materials and practices to illuminate hidden power structures, imagine alternative modes of action, suggest new forms of collective intelligence and even become agents of change? What are the skills and responsibilities that artists can develop in the present socio-ecological context?

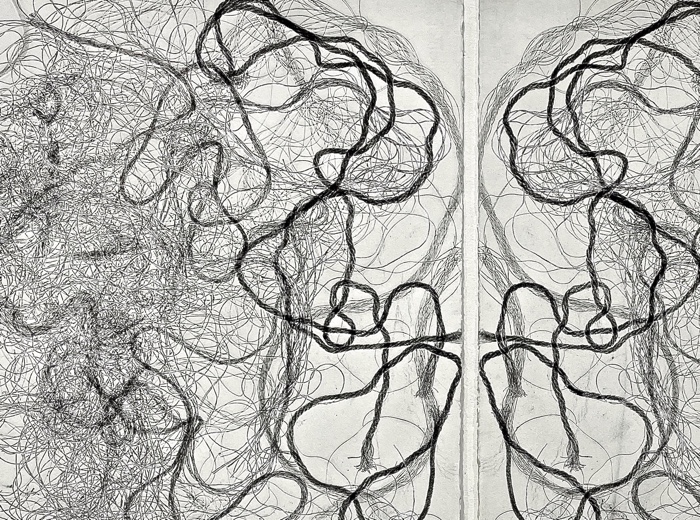

Lydia Halcrow, Ghost Nets (Strandline), 2021. Photo: Owain Jones

Artworks that raise awareness are crucial (the editors give the example of Angela Palmer’s Ghost Forest) but, often, all they generate is despair and defeatism. Hence, the book spotlight on creative initiatives that help us manage or transform our individual and collective grief by channelling our capacity for creation, empathy and repair.

I liked the publication for its interesting perspectives and uplifting mindset. Part of its content is great. Part feels like a paraphrase of ideas that deserve to be spread widely but that have been explored again and again over the past 10 to 15 years. Still, some of the essays are worth a read:

431art, botanoadopt.org, 2009-ongoing

431art, botanoadopt.org, 2009-ongoing

Carsten Höller and Stefano Mancuso, The Florence Experiment, 2018. Photo: Martino Margheri

Carsten Höller and Stefano Mancuso, The Florence Experiment, 2018. Photo: Martino Margheri

Philosopher and curator Sue Spaid delineates the history of scientific research and artistic experiments that illuminate the intelligence and otherwise difficult to perceive life of plants. I learnt so many fascinating facts and ideas from her essay. Such as the backlash to Carl Linnaeus’ revelation that flowers have sexual organs. It was 1753 and his classification of about 7000 plants in terms of their sexual reproduction sparkled horrified comments from his critics (who were referred to as “anti-sexualists”.) Some even described his systems as “loathsome harlotry.”

It took decades before philosophers stopped mischaracterising plants as being sexually indifferent. Even nowadays, with Plant Neurobiologists and other researchers helping us better comprehend the otherwise imperceptible events that define plant life, most people (outside indigenous traditions, as the author notes) find it difficult to acknowledge plant agency.

Spaid also surveys art projects that attempt to reveal what our flawed human senses fail to notice. From Rob Carter’s co-creations with GM soybeans to 431art’s adoption programme for abandoned plants, the artists manage to draw us closer to the vegetal universe. These artistic practices add affective and intuitive layers to scientific findings, making us mindful of plants, reminding us that even life that we assumed to be “immobile” is worthy of care and protection. Which perhaps constitutes the first barrier against ecocides.

Silent Trail on the Cuifeng Lake in Paiping Mountain, Taiwan

Some of the texts in the book focused on the use, by artists, of an embodied, multisensory engagement with the surrounding in order to help us re-wild all our senses and better perceive and acknowledge the more-than-human worlds.

Field recordist Laila Chin-Hui Fan, for example, convinced a government agency in Taiwan to set up a special trail dedicated to listening. Located along the shores of Cuifeng Lake in Paiping Mountain, the Silent Trail opened in 2018. Since then, it has been guiding the public towards recreational behaviour that take into account all their senses and make them more likely to be mindful of the fauna and flora that surround them.

In her essay, Patricia Brien explains how she used her curator role to be a cultural agent of social change in her community. In 2019, she invited artists to respond to the opening of a waste incinerator in a green rural area near Stroud, UK. Called Incendiary, the exhibition not only highlighted the social inequalities engendered by ecocide (and in particular by the release of small invisible particle matter), it also highlighted the importance of collaborations between artists, scientists and environmental activists to exchange situated knowledge and draw strength from it.

Artist and environmental activist Alison Harper and researcher Sarah Chave from the University of Exeter write about deep materialism as a strategy to resist toxic over-consumption and reappraise the value of all matter, even matter we would normally consider to be waste. The concept of deep materialism is illustrated by Harper’s use of industrially processed material in her practice. She unmakes, largely by hand, objects and matters that have lost their value and transforms them into new artefacts. By doing so and by carefully assessing the carbon footprint of the artistic process, she deepens her connections with the material world and thus repairs her relationship with it.

Image on the homepage: The Florence Experiment, 2018. At Palazzo Strozzi, Florence. Photo: Attilio Maranzano.

Related books and stories: The Funambulist: Forest Struggles, Oliver Ressler. Barricading the Ice Sheets, Vegetal Entwinements in Philosophy and Art, Green Revisited: Encountering Emerging Naturecultures, “Have we met?” A multispecies approach to the planet, PlateauResidue: the artists whose daily life reflects their fight for the climate, etc.