A review of Censored Art Today, by journalist and Chief Contributing Editor of The Art Newspaper Gareth Harris. Published by Lund Humphries.

Cleon Peterson, MAGA Republicans Want to Control Your Body, 2022. Billboard Companies Have Censored Artists’ ‘Inflammatory’ Designs for a Pro-Voting Campaign in Georgia

Emin Alper, Burning Days (Kurak Günler), 2022. Photo

In March 2022, Russian artist Sasha Skochilenko swapped price tags in a supermarket in Saint Petersburg with little paper labels containing information about the invasion of Ukraine. She was arrested and remains in custody, facing a 10 year sentence. More recently, Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism demanded that filmmaker Emin Alper pay back the funds the ministry had given to support the film — with interest. The film is Kurak Günler (Burning days) and the spurious pretext for the governmental request is that the film is an “LGBTQ propaganda film.”

Unfortunately, Skochilenko and Alper are not the only artists who have been punished for expressing their views or simply for tackling issues that some authorities find unpalatable. A growing number of creative practitioners across the world have been censored, attacked, arrested or otherwise silenced in recent years. In its State of Artistic Freedom Report 2022 (PDF of the report), Freemuse, an international NGO advocating for freedom of artistic expression and cultural diversity, details the extent of oppression and violations of artistic freedom.

In 2021, more than 1,200 violations of creative freedom were documented. Among them is a record number of 39 artists who were reportedly killed that year. More than 500 artists faced legal consequences for challenging the authorities, public figures and religious and traditional values. Women, the LGBTQIA+ community and artists of a minority ethnic background are disproportionately victims of this deterioration of artistic freedom.

Why is censorship on the rise? What forms does it take? Who are the censors and who are their targets? What are the consequences of blacklisting art?

In Censored Art Today, Gareth Harris attempts to explore some of these questions. His research concentrates on 5 main areas: political censorship in China, Cuba and the Middle East; the suppression of LGBTQ+ artists in ‘illiberal democracies’; the algorithms policing art online; Western museums and ‘cancel culture’; and the narratives around ‘problematic’ monuments.

Wang Xingwei New Beijing, 2001. One of the paintings removed from an exhibition at M+ Sigg Collection, Hong Kong

Chapter 1 looks at the rising subjugation of artists and museums in Hong Kong and Cuba just as their inhabitants had been experiencing wider freedom both physically and virtually. In Hong Kong, the Chinese Communist Party is not only clamping down on freedom of expression but also is also intent on rewriting history. In Cuba, the government of Miguel Díaz-Canel has passed Decree 349 and Decree 370. The first one prohibits artists, including collectives, musicians and performers, from operating in public or private spaces without prior approval by the Ministry of Culture. The second curbs communications on social media.

Instead of silencing artists, conservative, autocratic and oil-rich Middle Eastern states are adopting a more insidious approach. In order to boost their soft power credentials, they deploy cultural institutions for political ends, ‘artwash’ their national brands and detract attention from human rights issues.

Elżbieta Podleśna, Black Madonna of Częstochowa with rainbow halos, 2019

Dorota Nieznalska, Pasja/Passion, 2001 (photo)

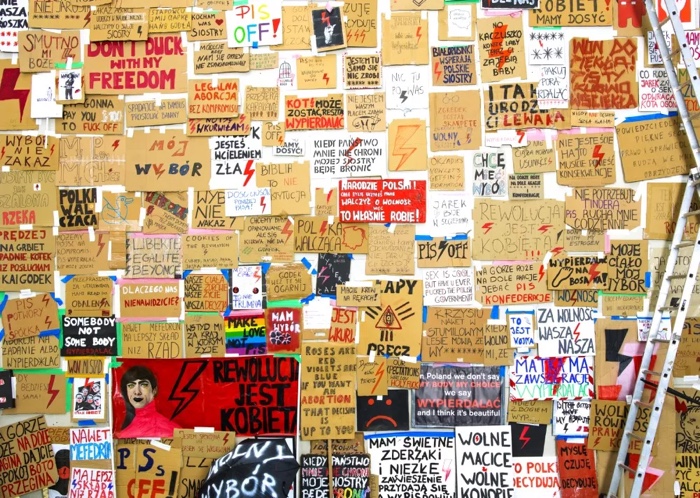

The work “Banners from Plac Wilsona – 30.10.2020” by Krzysztof Powierza consisted of banners from protests against the tightening of the abortion law in Poland was censored for being too politically-charged (photo)

The chapter dedicated to the Suppression of LGBTQ+ Artists in ‘Illiberal Democracies” examines how governments and religious groups in Turkey, Brazil and Poland use legislation and other tactics to quash LGBTQ+ artists and art institutions hosting shows focused on gender, sexuality and anti-racist themes.

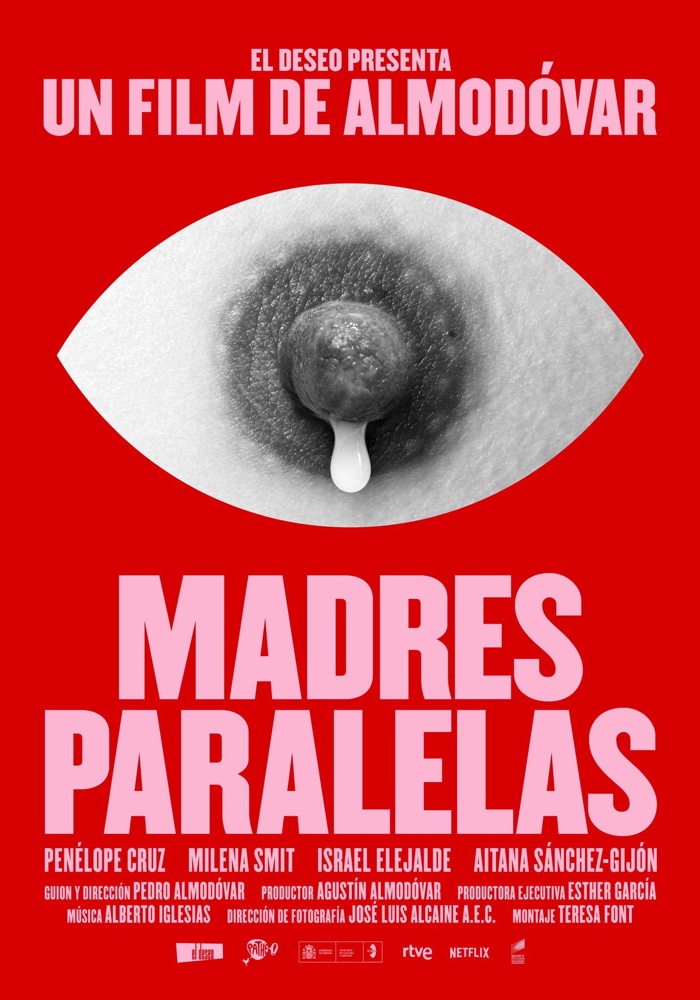

Instagram eventually decided to override its nudity ban for a poster designed by Javier Jaén to promote Pedro Almodóvar’s film, Madres Paralelas. Unfortunately, says The National Coalition Against Censorship, “most artists are not Pedro Almodóvar”

Vienna strips on OnlyFans. Vienna museums open adult-only OnlyFans account to display nudes

“Cultural capital, or the soft power of art, seems to hold little currency among companies such as Facebook and YouTube, whose appeals procedures have become only slightly more transparent over time,” writes Harris in chapter 3. That section of the book attempts to make sense of the pervasiveness of censorship on social media, a space where artists build critical profiles and where art institutions promote their programmes. Unfortunately, social media are also rife with technological flaws and with ambiguous, if not downright opaque and shifting, community guidelines.

Just like what happens with the forms of censorship described in previous chapters: artists often have to self-censor by carefully filtering and modifying their works.

Philip Guston, Riding Around, 1969. More background in Artists Speak against the Postponement of ‘Philip Guston Now’

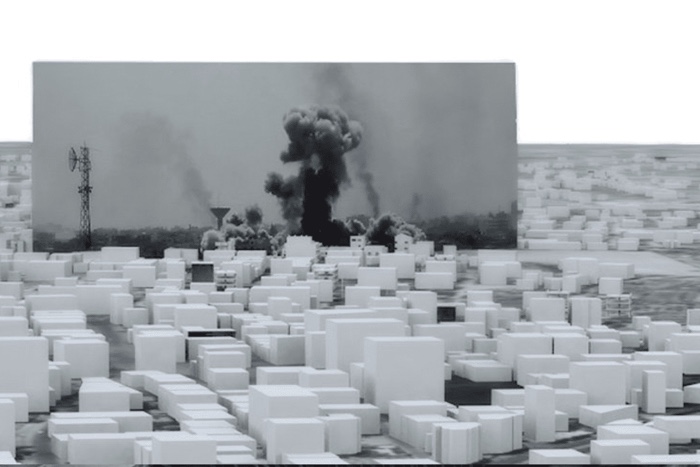

A legal smear campaign against Alistair Hudson, the museum director of the Whitworth art gallery in Manchester after he refused to remove a statement of solidarity displayed in Cloud Studies, a show by Forensic Architecture

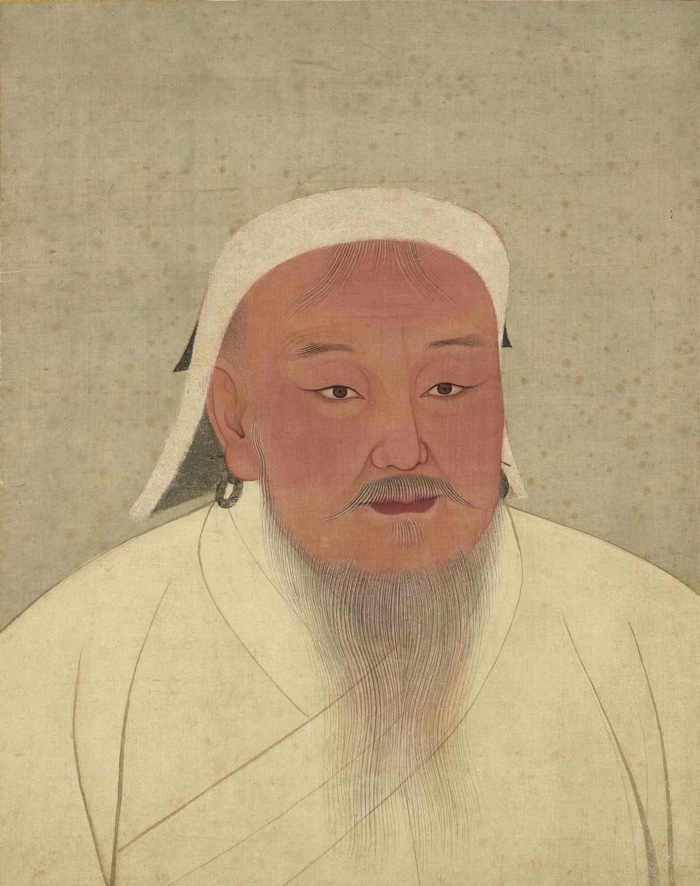

Imaginary portrait of Genghis Khan (14th century), National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Genghis Khan exhibition in France postponed after Chinese authorities demand words including ‘Genghis Khan’, ‘Empire’ and ‘Mongol’ be removed from the show

The chapter about Western Museums and ‘Cancel Culture’ gives a critical overview of the dilemmas and pressures that public institutions face today. Museums are expected to act as platforms for artists, enabling creative practitioners to express themselves freely without external constraints. They should also respect a series of diversity and inclusion imperatives, be more sensitive to the concerns of an increasingly engaged activist audience and keep an eye on the necessity to retain public and private funding.

Harris gives examples of institutions that manage to navigate the various challenges and expectations. In 2018, for example, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia kept an exhibition of Chuck Close photographs open in spite of allegations of sexual misconduct against him. Instead of shunning debate, PAFA added a parallel show of acclaimed women artists called The Art World We Want and invited the public to share their opinions about the necessary steps that would lead to a more equitable and diverse art world.

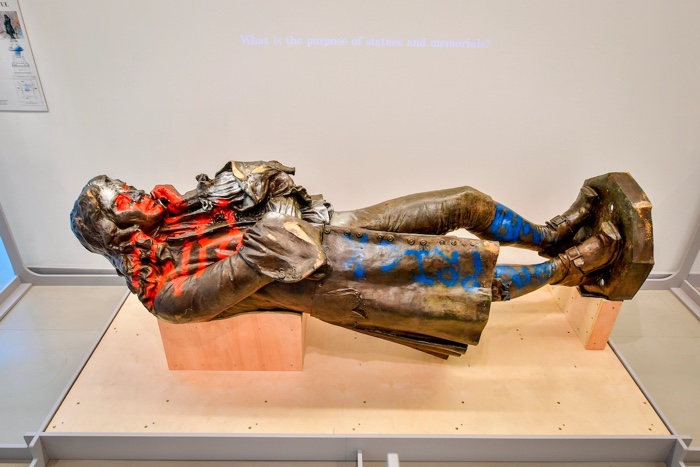

The statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston, which was retrieved from the water after being toppled during a Black Lives Matter protest, is on view at the M Shed museum in Bristol

The final section, The Narratives around ‘Problematic’ Monuments, explores the tensions between what constitutes, for some people, a source of national pride and what remains, for others, a cruel reminder of colonialism and a testimony to the continuity between the injustices of the past and the present.

The movement to tear down controversial historical monuments presents a reversal of the power dynamic discussed in earlier chapters. Statues do not fall because those in power say so. They fall because citizens take the initiative. The other difference is that removing monuments do not necessarily amount to censoring. The request to remove a monument is accompanied by debates on how and whether it should be moved elsewhere, put in a broader context or accompanied with nuanced narratives.

Monster Chetwynd, A Monument to the Unstuffy and Anti-Bureaucratic, 2019, from Testament at Goldsmiths CCA. Photo: Rob Harris

Censored Art Today is insightful, easy to read and packed with analyses of episodes of art suppression from all over the world. I particularly welcomed the balanced/careful perspective in the evaluation of the examples studied in chapters 5 and 6.

Censored Art Today is both disheartening and comforting. The silencing of artistic expression results not only in loss of professional opportunities for artists but also in widespread self-censoring. On the bright side, audiences seem to be more attuned than ever to the concerns behind the artworks or exhibitions judged by some to be contentious. Many of the challenges that artists encounter today are also relayed in online art publications, and in particular blogs like Hyperallergic or Harris’ own Trigger Warning. I’d also recommend anyone interested in the issue to follow the work of Artists at Risk Connection, an organisation that safeguards the right to artistic freedom of expression and shares the stories of persecuted artists.

Related (and somewhat related) stories: Nonument, the hidden, abandoned and forgotten monuments of the 20th century (part 1) and (part 2: How artists deal with old monuments that polarise opinions); Whistleblowing for Change. Exposing Systems of Power & Injustice; Global Control And Censorship. A quick tour of the RIXC festival exhibition; János Brückner. Making visible the influence of politics on culture; La Movida. Or the need for countercultural movements; Unauthorized images: when absurd gag laws call for absurd (but witty) artworks, etc.