Very little is known about Emilie Rosalie Saal. She was born in Estonia, studied in Russia and lived from 1899 until 1920 in Indonesia with her husband Andres Saal who was the head of the military cartography department of the Dutch colonial army. At the end of Andres’ mission in Indonesia, the couple moved to Los Angeles.

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

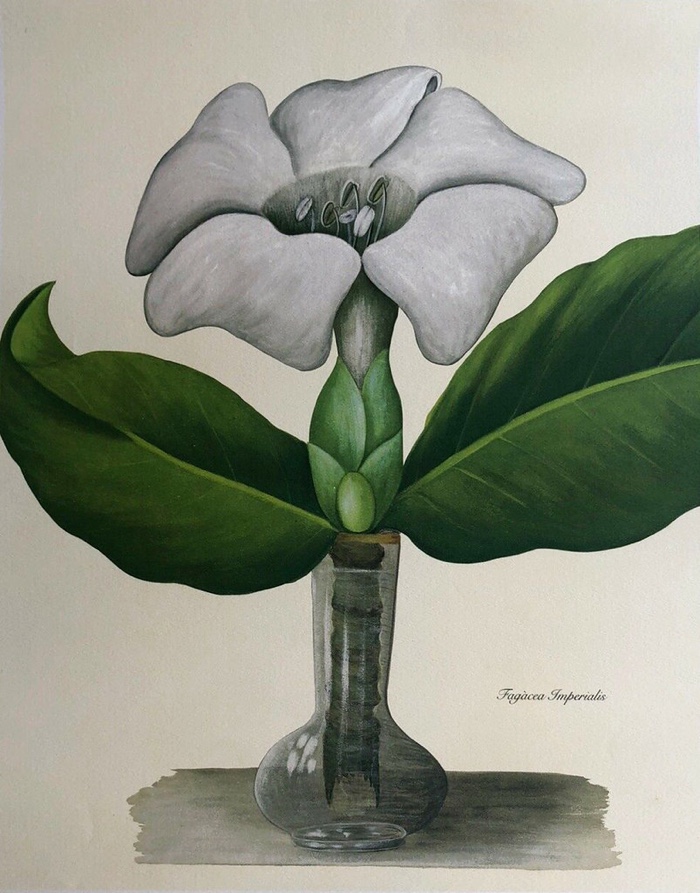

Emilie Rosalie Saal, Michelia Campaca, original ca 1910, newly printed 1995

Emilie Saal and Andres Saal on their mansion veranda in Java, c. 1910. Courtesy of the Estonian Literary Museum

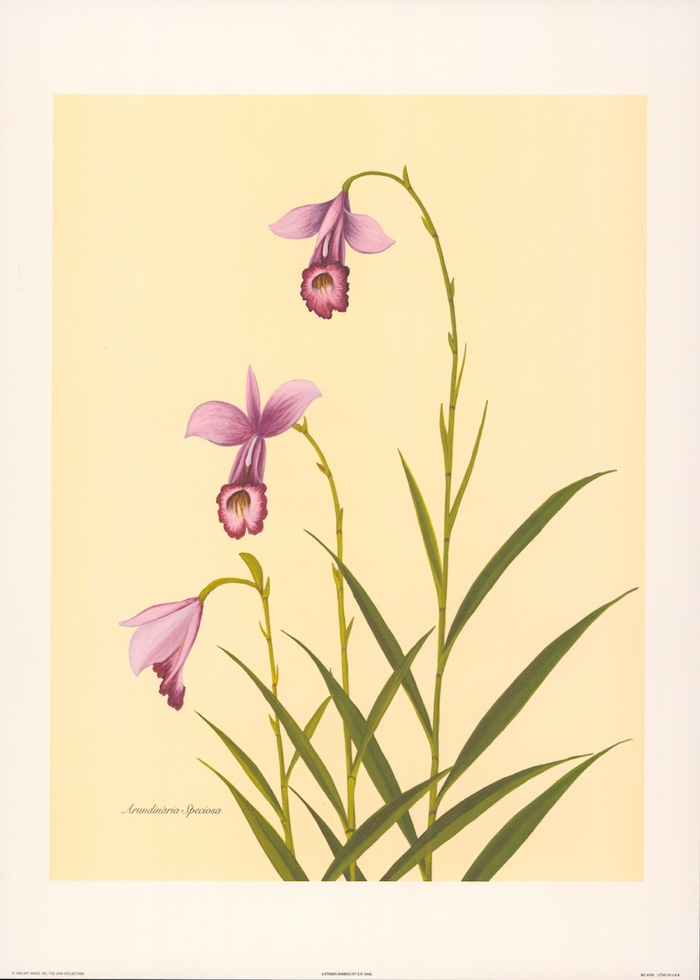

Emilie Rosalie Saal drew botanical artworks during their stay in Indonesia. She would go on expeditions, hunting for tropical flora and in particular for orchids. Today, you can buy orchids online or in supermarkets but at that time, they were very rare and only the elite could afford to collect them.

Emilie Saal was an ambiguous figure. Once a colonial subject in Estonia —then part of the Russian Empire, she eventually became an elite member of Dutch colonial society and enjoyed the privileges only white people could aspire to in Indonesia. As a woman living in a patriarchal society, she was merely a footnote in the biography of her husband who has a place in Estonian history as a romantic writer. However, as a member of the colonising community, she could rely on the labour of Indonesian servants to give her enough free time to pursue her activities of painting, studying botany and travelling around the country looking for sought-after exotic flora.

While Andres was mapping the exotic land, Emilie mapped the exotic nature. As such, both made a significant contribution to the colonial system in the Dutch East Indies. Maps have always been a form of political control by Western colonial powers. They were evidence that the colonisers owned a territory. Just like the Europeans rarely used information from local communities to draw their maps, Emilie Saal depicted rare plants against abstract backgrounds, erasing their place of origin, their context and indigenous knowledge of nature.

Andres Saal and servant on a rubber plantation. Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

Kristina Norman, Orchidelirium (film still), 2022. Photo: Erik Norkroos

Emilie Saal in collaboration with Andres Saal, Tropical fruit still-life, overpainted photograph, c. 1910-1920. Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

Even though Emilie Rosalie Saal is a rather obscure figure in Estonian history, artists Kristina Norman and Bita Razavi, in close collaboration with curator Corina L. Apostol, have made her the focus of the Estonian pavilion at the Venice Biennial.

Titled Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance, the exhibition uses Saal’s artistic work and personal story as a case study to expose entangled histories of colonialism, neo-colonial structures, ecological exploitation and their enduring socio-political ramifications in Estonia and Indonesia. The word Orchidelirium refers to the orchid craze that gripped Europe over a century ago. The subtitle An Appetite for Abundance was inspired by a painted photograph from Java (taken by Andres Saal and overpainted by Emilie) that depicted a opulent still life of fruit and vegetables. The orchid fever was part of the tradition of collecting “exotic” curiosities in the colonies, trafficking them and showing them in zoos and botanical gardens in imperial metropoles.

Orchidelirium illustrates the history of colonial and ecological exploitation hidden behind the beauty of tropical plants. Today, the exploitation of palm oil and deforestation in Indonesia is happening at the same time as local companies are creating so-called shelters for rare orchids which they wish to save from extinction. And at the same time as wildlife contraband is growing to be an extremely lucrative business. The rarer (or the most endangered) the species, the more profitable they are, dead or alive.

Emilie Rosalie Saal, Bamboo Orchid, ca. 1910-1920

Bita Razavi, Kratt. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance, the Estonian Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 2022. Photo by Luke Walker

Bita Razavi, KRATT: DIABOLO №3 (detail), 2022. Orchidelirium. An Appetite for Abundance, the Estonian Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 2022. Photo by Luke Walker

Bita Razavi’s installations inside the pavilion critically address who and why should speak about privilege and in what context and engage audiences to reflect on their own.

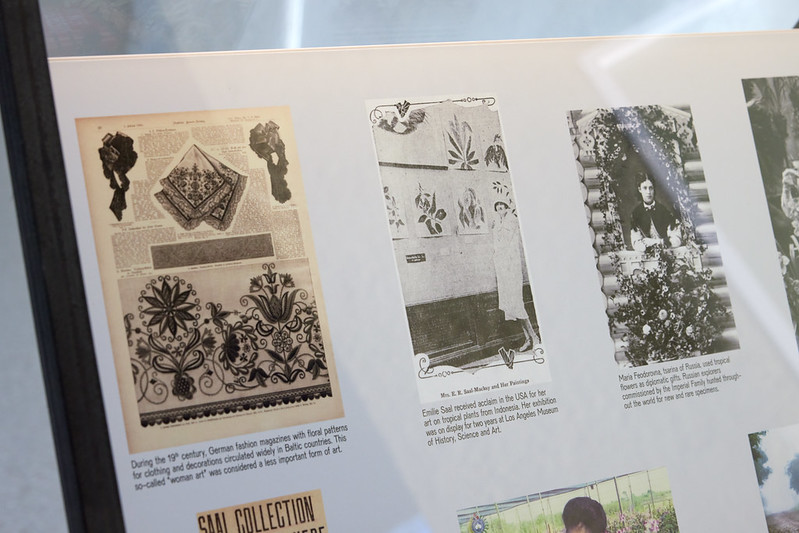

Razavi’s most stunning installation in the pavilion evokes the Kratt, a mythological creature from Estonia. Its master forced the Kratt to work without respite, making it mostly steal and bring various goods for him. In Razavi’s work, the Kratt is a huge spider-like sculpture that constantly reprints Emilie Rosalie Saal’s botanical drawings.

The work highlights the role that modern printing technology played in making the colonial worldview more tangible and acceptable for Western audiences. They enabled the wide distribution of botanical images, maps and accounts that promoted a positive narrative about the colonies.

According to the artist’s website, the version of the work at the biennial has been censored: the archival images of destroyed landscapes that document conditions of colonial extraction of labour and soil that should have appeared on the lower belts of the sculpture have been removed without the artist’s consent. The censored images would have completed Emilie’s representation of exotic flora by replacing it in its original and extractivist context.

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Teaser for the Estonian Pavilion 2022. Artist Kristina Norman is introducing her works

Kristina Norman addresses the relentless exploitation of distant landscapes by the Global North in her film trilogy. “Rip-off” looks at the invisible labour necessary to enable rich Europeans to indulge in the orchid craze at the time of Emilie Saal. “Thirst” and “Shelter” are set in the present day. The former reveals how peat is extracted at low costs from Estonian bogs and used as a substrate to grow orchids in the Netherlands. “Shelter” looks at the ongoing exploitation of orchids grown, cloned and mass packaged in nurseries in the Netherlands.

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Dancer Eko Supriyanto contributes to the pavilion with ANGGREK, a video work that is looking at the histories of sites, like the botanical garden of Bogor, where Emilie Saal went to paint orchids. The lush garden was built on a sacred forest of trees on indigenous land, despite local protests. It was razed and replaced with a European botanical institute.

The exhibition also charts gestures of resistance and remembrance of the sites that have been forever altered. For examples, several images document how local communities protest against the neocolonial extraction of marble without consent. Aleta Braun, for example, led women of the indigenous Mollo community in Indonesia to symbolically weave intricate tapestries to protect their land from mining companies. The women of Kendeng set their feet in cement and protested outside the presidential palace in Jakarta to stop a mine in their lands. they feared would pollute their community’s water and damage their ancestral land.

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

This year, Estonia is a guest of the Rietveld Pavilion (aka the Dutch pavilion) in the Giardini della Biennale in Venice. This is not the first time Estonia hacked its way inside the famous garden where it doesn’t have a permanent pavilion. In 2008, during the Architecture Bienniale, the country took over part of the garden by joining the German and the Russian pavilion with a bright yellow section of a natural gas pipe in reference to Nord Stream, which was then a controversial Gazprom project many neighbouring countries were concerned would result in unpleasant political and ecological impacts.

More images from the Estonian pavilion:

Emilie Rosalie Saal, Fagacea Imperialis II, original ca 1910, newly printed 1995, litography

Emilie Rosalie Saal on horseback on Java Island. Stereo photo: Andres Saal, ca. 1910-1920. Courtesy of the Estonian Literature Museum

Gardener packing plants inside Wardian cases at the Buitenzorg Botanical Garden (Kebun Raya Bogor), 1913. Courtesy of the Tropenmuseum Collection, Amsterdam

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance. Installation view. Photo by Luke Walker. CCA Estonia

Related stories: Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest, Biopiracy, the new colonialism, How do we make our genetic, biological and digital heritage future-proof?, Propositions for Non-Fascist Living. Tentative and Urgent, etc.