Since the coronavirus has put a stop to my visits of exhibitions, conferences and festivals, I thought I’d use the pause as an opportunity to share with you some of the artworks that I keep babbling about whenever I give a workshop or a talk but that I never took the time to write about.

Starting with Yann Mingard‘s Deposit. The photo series investigates the Western drive to secure our genetic, cultural, biological and digital patrimony behind heavy doors.

Yann Mingard, The French Horse and Riding Institute (National Stud Farm), Landivisiau, France, 2011. Dummy mare for harvesting stallion sperm © Yann Mingard

Yann Mingard, Entrance to Bahnhof.se, “Pionen”, a data center in Stockholm, Sweden, 2011

The photos mostly focus on Europe, a continent that now lives on its past glories, a region clinging to the spoils of colonialism and afraid of environmental disasters, low birthrates, globalisation and of losing its significance in the world.

The new gold, jewellery and antiques, the new treasured possessions that need to be kept safe for future generations are now seeds of food crops, tissues of endangered animal species, human genetic material and electronic data.

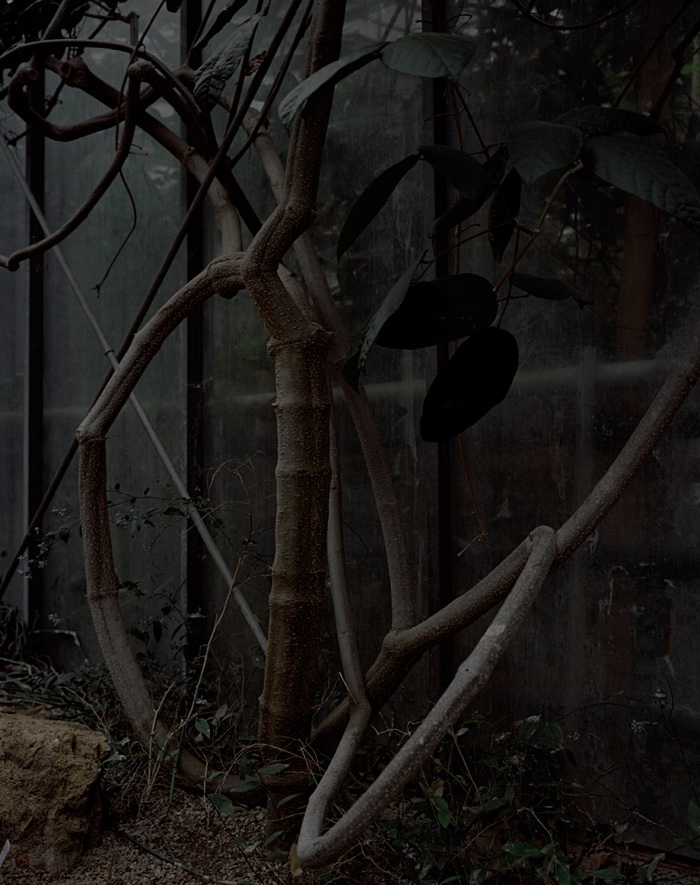

Mingard’s portrait of a society that tries to protect its heritage is disquieting. If the images are dark and almost always devoid of any human figure, it’s because most of that precious material is being preserved in dark, claustrophobic places. Often under the earth and away from public scrutiny.

Deposit suggests a future in which the ingredients that make our planet such a wonderful place have been stored (often with the assistance of mysterious private interests) in bits and pieces inside vaults and labs, to be reanimated whenever we desperately need them. Let’s hope it’s as simple as that.

The research project is articulated around four chapters ”Plants”, ”Animals”, ”Humans” and ”Data”. The chapter dedicated to animals was the one i found most moving and, at times also, infuriating.

Yann Mingard, Creavia, Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, France. Bull sperm bank. Covering room, 2011

Yann Mingard, Creavia, Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, France. Bull sperm bank. Laboratory, 2011

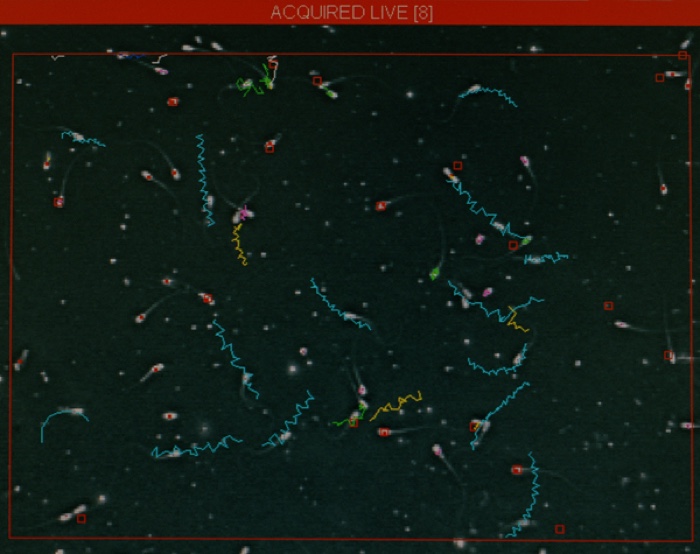

Yann Mingard, Creavia, Saint-Aubin-du-Cormier, France. Bull sperm bank. Spermiogram, 2011

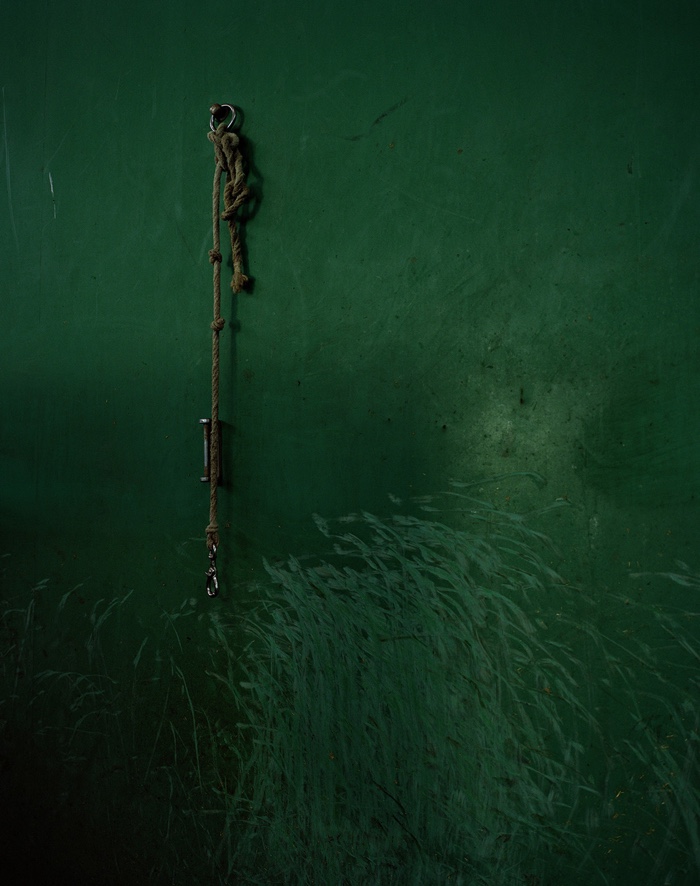

Yann Mingard, Swiss National Stud Farm, Avenches, Switzerland. Harness for a mare in heat to be used as a stimulus for assisted reproduction when a stallion mounts a breeding dummy, 2011

Swiss National Stud Farm, Avenches, Switzerland, 2011

Swiss National Stud Farm, Avenches, Switzerland, 2011

On the one hand, it shows how the sperm of bulls and stallions is collected almost daily to be then put inside straws that will be sold for artificial insemination. Most of these animals never see a cow or a mare. Instead, they get, a plastic dummy, an aerosol spray that reproduces the smell of a female on heat, an artificial vagina (if ever you were curious about the size of the contraption, i was shameless enough to search it for you), etc. I read that a few “lucky” fellows get to mount and inseminate females in the natural way, and the semen is then extracted from the cow. Bull and hose semen are a big business.

Yann Mingard, Deposit. Frozen Ark, The University of Nottingham, United Kingdom, 2013

Organic material from animals is also collected in the hope that we can save, using cloning or gene-editing technology, some of the many species that are not safe in the wild anymore and that disappear at an unprecedented rate.

Nottingham University’s Frozen Ark project holds 48,000 DNA and cell samples from 5,500 of the most endangered species. In some cases, it also hosts the actual species including this critically endangered snail, found on just one mountain top in Japan.

Yann Mingard, Zoo Basel, Switzerland. Malayan sun bear, or “honey bear”, 2013

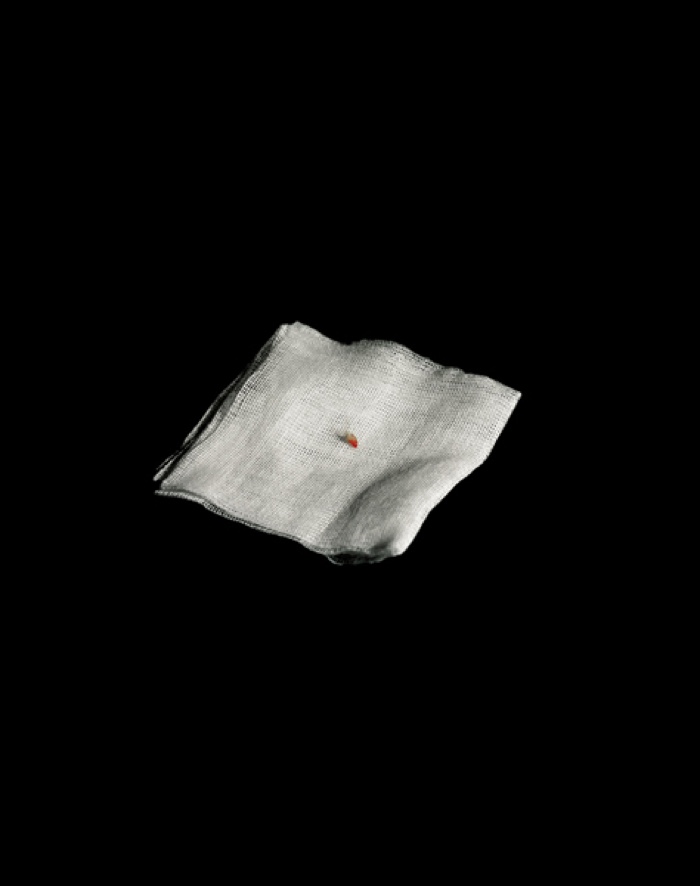

Yann Mingard, Zoo Basel, Switzerland. Malayan sun bear biopsy. Sample of tissue and hair for low-temperature preservation, 2013

The Malayan sun bear above was undergoing a biopsy to provide a sample for preservation in Zoo Basel’s blood and tissue bank. In the wild, the bear is threatened by deforestation and commercial hunting.

Around the world, our food future is preserved in the form of vast quantities of seeds inside bunkers, vaults, plastic bags, aluminium boxes and other non-organic containers and architecture.

Yann Mingard, Le Conservatoire Botanique National de Brest, France, 2011

Yann Mingard, Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Arctic Svalbard Archipelago, Norway. Mountain location of the seed vault, 2009

Yann Mingard, Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Arctic Svalbard Archipelago, Norway, 2009

Svalbard Global Seed Vault offers a striking example of how seeds are stored in some of the most inhospitable places for food crops. Buried inside a mountain in the Norwegian Arctic, the “doomsday vault” uses permafrost and deep rock to freeze our food future and preserve it from the threats of nuclear fallout, war, natural disaster or the ongoing mass extinction of plant species.

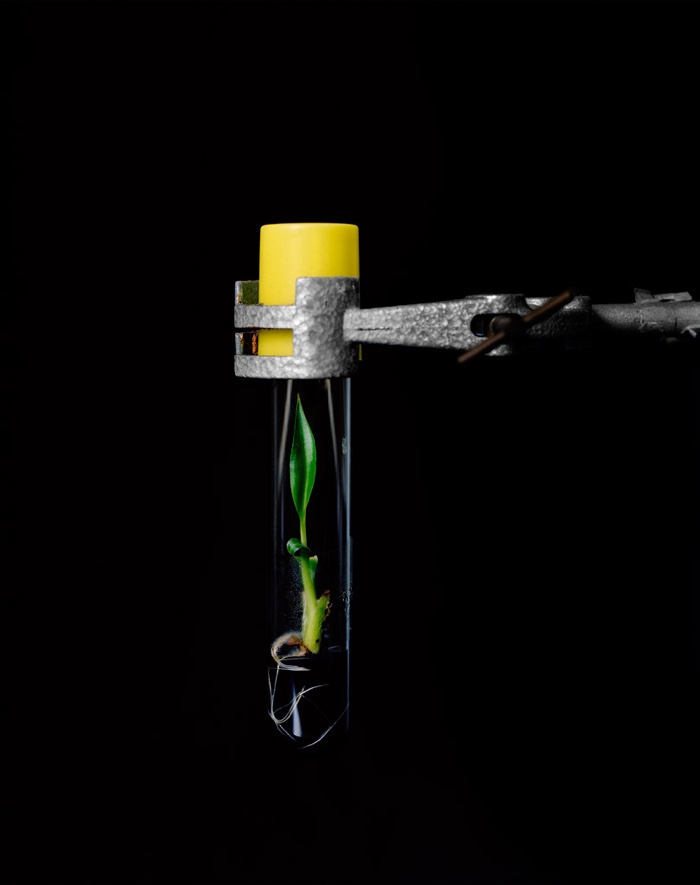

Yann Mingard, Deposit. Laboratory of Tropical Crop Improvement, Catholic University of Leuven,Belgium, 2010

A research legacy from the Belgian Congo, the Laboratory of Tropical Crop Improvement at the Catholic University of Leuven, is home to the world’s largest collection of banana samples. The image above shows the in vitro cultivation of banana plants over a period of 30 to 45 days.

Yann Mingard, N.I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2012

Russia’s largest seed bank is the Vavilov Research Institute established in 1921 in St Petersburg.

Nikolai Vavilov, the head of this institute from 1924 to 1936, disagreed with agronomist Trofim Lysenko‘s anti-Mendelian doctrines and pseudoscientific ideas. Unfortunately, Lysenko’s beliefs won Stalin’s favours.

Scientists who refused to renounce genetics were dismissed from their posts. Many were imprisoned. Vavilov was one of them. He died in prison in 1943.

The institute is also famous because, during the 28-month-long siege of Leningrad, some of the botanists lived inside the building to protect its extensive seed collection from rats and from their own hunger. Many of them died of starvation when they could have sprouted and eaten the seeds.

The research institute has now to face new threats: shocking underfunding and real estate development.

A third chapter in Mingard’s work investigates how (mostly wealthy) humans attempt to ensure a long and healthy life for themselves.

Yann Mingard, Swiss Stem Cells (SSC), Lugano, Switzerland. Private umbilical cord blood bank. Kit for umbilical cord stem cell collection, 2011

Yann Mingard, Deposit. deCODE genetics, Reykjavik, Iceland, 2013

500,000 pipettes of blood are stored at -25°C in the basement of deCODE genetics, an Icelandic biopharmaceutical company that aims to use population genetics studies to identify variations in the human genome associated with common diseases, and to apply these discoveries “to develop novel methods to identify, treat and prevent diseases.”

Yann Mingard, CRYOS International, Aarhus, Denmark. Private human sperm bank. Semen straw ready for freezing in liquid nitrogen, 2010

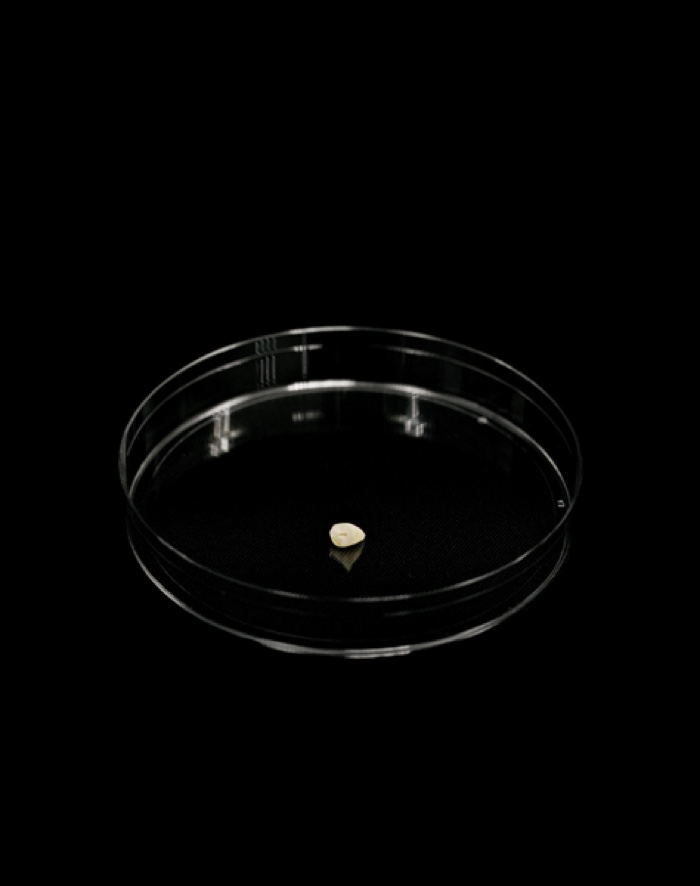

Yann Mingard, Future Health Biobank (FHB), Nottingham, United Kingdom. Milk tooth, 2013

Future Health Biobank is a private company that processes and stores cord blood, cord tissue and dental pulp. These sources of stem cells may one day be used to treat a number of health conditions conditions suffered by the donor (or their mother.)

Yann Mingard, KrioRus, Alabushevo, near Moscow, Russia, 2010

This fibreglass vat is used for the cryopreservation of human bodies or brains

KrioRus, founded in 2005 by the Russian Transhumanist Movement, stores full bodies (or just the head) of its patients — dead people and animals, in liquid nitrogen, in the hope that someday it might be possible to revive them using technologies that still need to be invented.

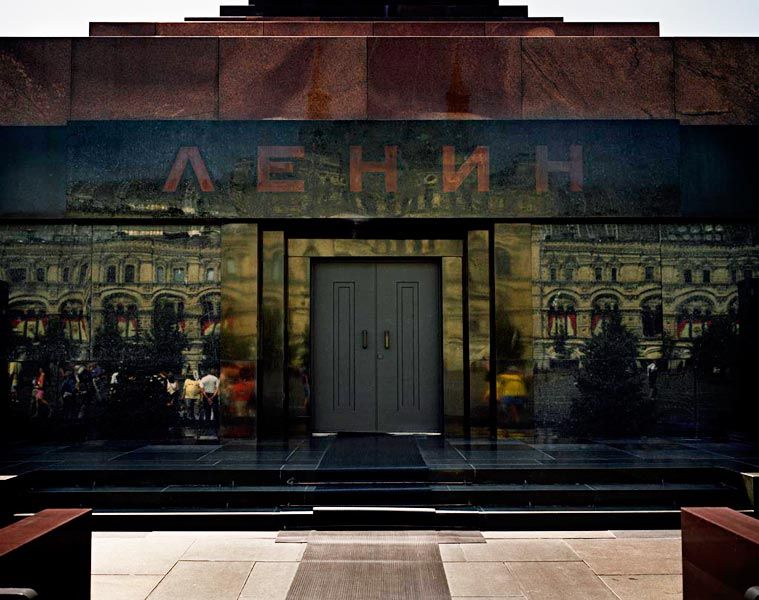

Yann Mingard, Lenin’s Mausoleum, Red Square, Moscow, Russia. The embalmed body of Lenin has been on display in this mausoleum since his death in 1924, 2010

Yann Mingard, The European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI), Hinxton, Cambridge, UK, 2013

Acting as a bridge between organic and digital storage, this test-tube contains Shakespeare’s sonnets, the audio of Martin Luther King’s I Have A Dream speech, a jpeg photo and a copy of the 1953 article by Crick and Watson describing the structure of DNA. This information was encoded and stored in synthesized DNA form back in 2013 at the European Bioinformatics Institute in the UK. DNA data storage could potentially be an energy-efficient way to archive digital data. All you need is a cold, dry and dark space. A bit like the seeds then.

Sensitive data have to be stored in super secure servers and hard drives. Who better than the Swiss know how to keep the secret of the rich…

Yann Mingard, Mount10, in Saanen-Gstaad, Switzerland, 2010.

A guard waiting for the armoured door to open inside Mount10. Different uniforms are used and adapted or omitted for client visits to accommodate the sensibilities of the client and the situation in the client’s country (war, dictatorship, coup d’état) (via.)

Known as “The Swiss Fort Knox”, Mount10 is a former Alpine military bunker converted into a super secure data centre. The clients are nation states, banks, corporations, individuals and other wealthy people or entities.

Yann Mingard, Bahnhof.se, “Pionen”, a data center in Stockholm, Sweden, 2011

Yann Mingard, Server cabinets, Bahnhof.se, “Pionen”, Stockholm, Sweden, 2011

A former Cold War military bunker refurbished in 2008 by Swedish Internet service provider Bahnhof, this data center is built to withstand a nuclear explosion and its backup generators are made from German submarine engines. It used to host Wikileaks servers.

Now I really need to get my hands on Mingard’s latest book: Everything is up in the air, thus our vertigo.

More information about the project in DEPOSIT, Wired, Financial Times, The Eye of Photography, Centre d’art GwinZegal youtube video.

Related story: Tomorrow’s tailor-made cows and The Seed Journey to preserve plant genetic diversity. An interview with Amy Franceschini.