With considerable delay and only pitiful excuses to justify it, here’s the second part of the notes I scribbled down during the conference AMBIVALENCES #1 which took place in early October in Rennes in the framework of the Maintenant digital art festival.

Joanie Lemercier and Pierre Vanni, Visual identity of the Festival Maintenant

Part 1 of my report summed up Bénédicte Ramade’s overview of the History of Ecological Art. Today, I’m sharing the notes I took during the round table “Digital Arts and Environmental Awareness” that discussed the ambivalent relationship between digital artists and the environmental crisis. Contemporary art has a massive ecological footprint. Contemporary art that uses -and sometimes even champions- digital tools also relies on technologies that generate extractivism, e-waste, human misery and unbridled energy consumption.

The participants to the panel were curator and COAL co-founder Loïc Fel, artist Claire Bardainne as well as artist and activist Joanie Lemercier.

Ambivalences #1 – Espace Tambour, Université Rennes 2. Photo: © Gwendal Le Flem / Association Electroni[k]

Let’s start this overview of the discussions with Joanie Lemercier. His experience as a digital artist who was not involved in activism and environmental struggles until recently will hopefully demonstrate that we can all put our skills and technological tools -even the ones that come with a calamitous carbon footprint- at the service of environmental activism.

Lemercier is an extremely successful artist. Together with digital art curator and producer Juliette Bibasse and sometimes other collaborators, he develops interactive installations that escape from screens and play with architecture, with viewers’ perception, with space geometry.

Daniel Chatard, from the series Niemandsland (No man’s land)

Daniel Chatard, from the series Niemandsland (No man’s land)

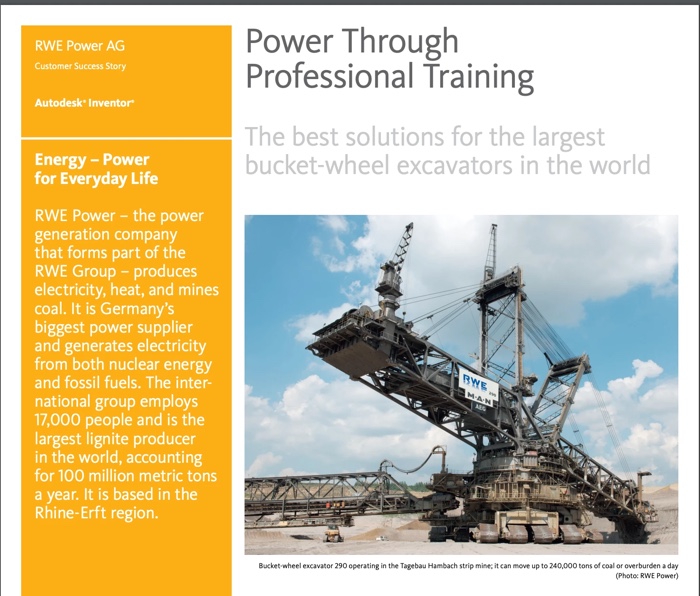

This year, he was showing one of his interactive pieces at the Maintenant exhibition but he also worked on the visual identity of the festival together with Pierre Vanni. Lemercier described the images they created as being half artistic projects and half militant works that build on his first-hand discoveries of the coal mining industry in Germany. Two years ago, after many years spent working inside a comfortable bubble, he got to visit the gigantic Hambach open-pit coal mine. The surface mine is operated by RWE to extract lignite, the dirtiest type of coal. Some call this open cast exploitation the ‘wandering’ hole because of the way it eats up the German landscape at the speed of 2,3 cm per hour. Nothing can stop the machines’ steady march. Not its disastrous ecological impacts. Nor the people who protest because their villages find themselves on the way of the excavating machines and have to be relocated.

Today 33% of electricity in Germany relies on coal. “When I do an exhibition and Germany and I connect a video projector, I burn coal,” commented Lemercier. The experience was eye-opening. Since then he has been trying to reduce his carbon footprint; taking fewer planes, cycling, recycling, etc. But, he believes, all these efforts pale in comparison with the magnitude of the CO2 emissions generated by the Hambach mine. And it is especially frustrating to realise how governments, fossil fuel energy lobbies and other important organisations attempt to put the blame on individuals.

Joanie Lemercier, projection to support the work of Ende Gelände, a civil disobedience movement occupying coal mines in Germany to raise awareness for climate justice

Joanie Lemercier, Autodesk earth impact, 2020

Instead of just feeling crushed and impotent, the artist decided to use his usual technological tools, his lasers, drones, cameras and projectors to get access to places that people would normally not be allowed to visit. He thus started filming the mining activities, documented the actions of activists, the police interventions, the destruction of forests and churches, the families forced to abandon their villages, etc.

While wondering who was responsible for these environmental disasters, Lemercier stumbled upon a company called Autodesk that makes software for architects. Autodesk is proud of its commitment to environmental sustainability. Yet, its tools are used by fossil fuel companies. The artist contacted them and exchanged with the CEO who was happy enough to chat about the company’s great environmental policy, about how they give free software to start-ups that produce electric bikes, etc. After a few exchanges of emails in which the artist asked them why they also work for the fossil fuel industry, they stopped answering. They even cancelled his account and erased their exchanges from their forums.

Joanie Lemercier, pop-up exhibition at Autodesk offices, 2019

After Autodesk cut all communications, Lemercier went to their offices in Montreal and installed a small photo exhibition at the entrance. It gave him and fellow climate justice activists the opportunity to discuss with employees, to comment on a number of unpleasant realities and enter into a dialogue. The company called the police.

RWE’s Tagbau Hambach coal mine with the famous bucket-wheel excavator, Germany. Photo: Joanie Lemercier

Autodesk’s RWE case study (via Drilled News)

Lemercier later designed Autodesk.earth, a website that exposes Autodesk’s impact on the environment. Not only did the website attract almost 3 million views but the artist also received emails from Autodesk employees concerned about the issue.

Joanie Lemercier, Climate Action in London

Joanie Lemercier, Climate Action in London. Photo: Anthony Jarman

He also used his own artistic skills to directly support the work of the activists. I think he did a great job at amplifying their voices and making their civil disobedience more visually impactful. For example, Lemercier used portable projectors to assist the actions of Extinction Rebellion, projecting their logos on Buckingham Palace and on Parliament Square in London. These were improvised, almost risk-free, ephemeral actions. The images of the interventions, however, remain. Sometimes, they even got used by the mainstream press and as such, they contribute to an aestheticisation of the climate justice protests.

Ambivalences #1 – Espace Tambour, Université Rennes 2. Photo: © Gwendal Le Flem / Association Electroni[k]

Loïc Fel‘s talk was packed with interesting ideas and artistic works that were new to me. Fel is a Doctor of Environmental Philosophy, an expert in sustainable development and the cofounder of COAL – COALition for art and sustainable development created in 2008 to connect artists and cultural actors working on environmental issues with institutions, NGOs, scientists and enterprises. If you’ve never heard of the COAL Prize, do check out the finalists of this year’s call dedicated to the erosion of biodiversity.

Fel focused his talk on the ambivalence in the relation between artists investigating ecological issues and the digital tools at their disposal. He explained that what distinguishes ecology from the other natural sciences, like zoology or biology, is that it is not exploring objects. Instead, ecology investigates the relationships between the elements. It is much trickier to represent or analyse relationships than to describe elements that can be isolated from one another and studied in lab settings. You cannot isolate an ecosystem to study it. Besides, studying relationships involves a notion of temporality. Works that involve ecosystem might be “finished” when we won’t be there anymore to experience them. Agnes Denes’ Tree Mountain, for example, will reach its maturity in 400 years time. It is thus sometimes difficult to make tangible the perception of the phenomena underway. The notion of space is challenging too. Ecology is made of hyperobjects (climate change, biodiversity erosion….), of phenomena that are immaterial in our daily perception of the world and that necessitate an exercise of critical thinking.

What makes digital tool interesting for artists is that they not only integrate the issue of time but they can also accelerate it or even extend it, making it easier to materialise otherwise intangible phenomena.

Environmentalist James Lovelock’s Daisyworld computer simulation imagine the simplest ecosystem and make it easier to explain the dynamic relationships between biodiversity and climate change.

Another important point raised by Fel is that, from the point of view of art criticism, we are confronted with a cultural movement that cannot be defined using formal elements or a style. What defines the artistic movement around ecological issues is not a series of formal aspects but the commitment, the involvement of the artists. The works are often (but not always) characterised by a certain level of eco-design and in particular by a desire not to rely on energy & resource-hungry digital technology.

Fel illustrated his points with a few artworks:

Olga Kisseleva, Urban Datascape, 2015

In 2015, during the COP21, Olga Kisseleva installed a gigantic QR code made of wood on the Banks of the river Seine in Paris. When passersby opened the QR code with their phone and started moving around, an Augmented Reality tool superimposed data about climate change and the environment onto the panoramic view of Paris. The project integrated the impacts of climate perturbations directly into the daily experience of the city and helped people visualise phenomena that they otherwise wouldn’t see. Urban DataScape also offered a non-commercial and socially-engaged reappropriation of the QR-code.

Stéfane Perraud, Sylvia, 2019

Stéfane Perraud‘s installationSylvia explored biodiversity in the Risoux forest located in the Haut Jura Regional Nature Park. Over the past few years, scientists have been recording the soundscape of the park. The aim of their efforts is to bring to the light the kind of biodiversity that we struggle to observe. The artist used this bioacoustics material along with scientific data related to biodiversity erosion and climate change to speculate on the soundscape of this natural forest habitat through time depending on how harsh environmental impacts will be in hundreds, even thousands of years from now. Will the forest become quieter and quieter to the point of being totally silent over time?

Elise Morin, Spring Odyssey, 2019-2020

Elise Morin, Spring Odyssey, 2019-2020

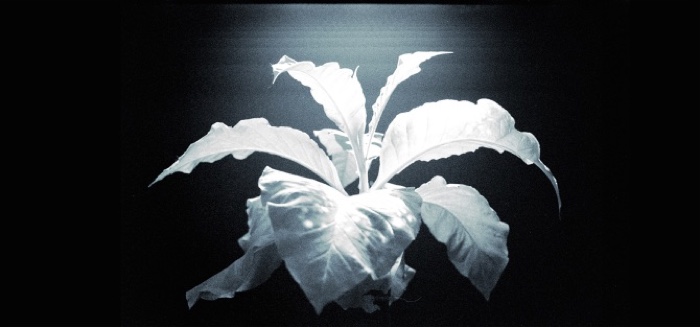

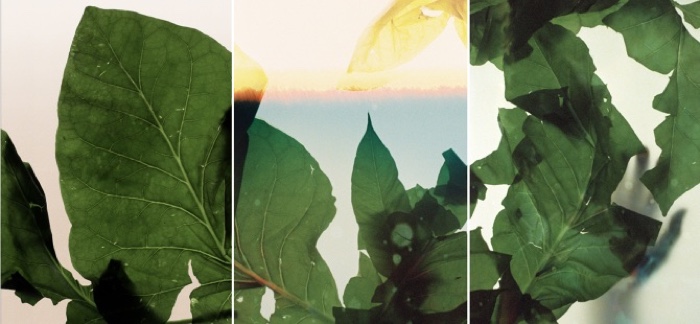

Biologists and NASA scientists are trying to discover the secret of resistance to radioactivity. Without it, there is no long-term future for humanity in outer space.

This secret might be hidden in terrestrial radioactive landscapes such as the area surrounding the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. The Ukrainian Red Forest, in particular, has become a space where plants had to adapt and develop forms of resistance. It is also an open-air laboratory where potential solutions can be tested out and where concepts of progress and nature can be confronted.

With Spring Odyssey, Elise Morin proposes to study scientifically the plants and stage the research but also to place it inside a digital simulation in order to test its effects.

Young shoots of tobacco plant carrying a natural mutation are grown in a laboratory to become bioindicators of radioactivity. A kind of organic version of the Geiger counter. The plant is also part of a VR environment: The red forest VR experience is a way to break a border that the body could not support naturally. A rite of passage to a new physical reality that blends myths, science and technology around a powerful invisible phenomenon and to question the fluctuating limits of our intuitions.

Rocio Berenguer, G5 Interespèces

Rocio Berenguer, G5 Interespèces

G5 Interespèces stages an important summit of big powers. However, this is not the G8 or the G20 summit: no governments nor financial powers are invited to join the discussions. The participants are the different kingdoms that share the planet: animal, mineral, vegetal, human and machine kingdoms (I want to apologise to the members of the Fungi Kingdom who, once again, have been cast aside.) They must debate on the possibilities of collaboration, fusion, determination, autonomy or independence of the different kingdoms in order to ensure the survival of life on a damaged planet.

Rocio Berenguer‘s project uses speculations and futuristic scenarios to open up perspectives for humans. It also relies on an AI that analyses in real time a questionnaire about the future of life filled in by the human members of the public.

The AI acts as a translation bridge between the different signals of each species. The problem is to translate the right signals into a language that each species can understand. The main issue is communication. How can we be understood without risking anthropocentrism?

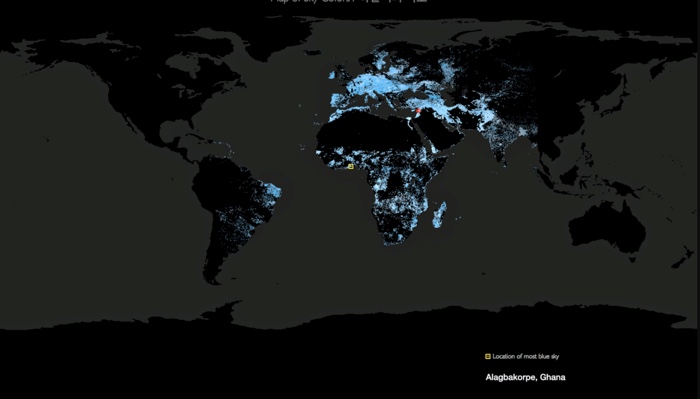

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Most Blue Skies

As Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway’s Most Blue Skies demonstrates, poetry too can play an important role in the desire to protect the environment. Raising awareness around problems is not enough, it has to be turned into action. The poetical can move us to the point that we want to act. Most Blue Skies is connected to a satellite system that analyses the colour of the sky in real-time. Satellite system and an AI identify the precise spot on Earth where the sky is perfectly blue. Combining atmospheric research, environmental monitoring and sensing technologies with the romantic history of the blue sky, the installation addresses our changing relationship to the skyspace as the subject for scientific and symbolic representation.

Ambivalences #1 – Espace Tambour, Université Rennes 2. Photo: © Gwendal Le Flem / Association Electroni[k]

Compagnie Adrien M & Claire B, L’ombre de la vapeur, 2018

Claire Bardainne, an artist, art director and co-founder of the Compagnie Adrien M & Claire B, told us about a work her collective developed around the Torula, or Baudoinia compniacensis, a mushroom native to the Cognac region that feeds on the vapours of the famous cognac brandy. Found on the walls of buildings near brandy maturation warehouses in Cognac, it’s been nicknamed “the whiskey fungus.”

Invited to create an interactive installation inside a building which walls were blackened by the fungus, Compagnie Adrien M & Claire B decided to pay homage to the fungus with an immersive installation that used digital tech to reveal the shadow of the vapour.

Visitors of the installation found themselves immersed in the dark and walking among tiny luminous cells. The particles moved in response to the visitors’ movements. Notes from “Cantique du champignon” (Canticle of the mushroom) accompanied the piece. The sound work, composed by Olivier Mellano, drew its inspiration from the DNA interpretation of the Torula mushroom. The protein music technique, aka DNA music, composes music by converting protein sequences or genes to musical notes.