The MAINTENANT Festival in Rennes is probably going to be my favourite digital art event of 2020. First, because it’s been one of the very very few cultural festivals I attended physically this year. Second, because of its accompanying conference, AMBIVALENCES #1, which looked at art and digital culture in the context of the environmental crisis.

Yannick Jacquet & Fred Penelle, Mécaniques Discursives. Place Sainte Anne. Photo: Gwendal Le Flem

The scholars, curators and artists participating to Ambivalences #1 examined the wide spectrum of creative practices that engage with pollution, invasive species, sea-level rise, fossil fuel, mass extinctions, etc. Can artists explore those issues in a way that is meaningful and impactful? Which strategies do they develop in order to break through the wall of attention fatigue? Can their work ignite a public (or even institutional) desire to change our relationship to the living?

I discovered so many interesting ideas and artworks at the conference that I’m going to translate my notes (the event was in French) and share them with you below.

I’m going to start with Bénédicte Ramade‘s talk. Next week, I’ll write about Manuela de Barros’ keynote and later I’ll sum up some of the key moments from the panel with philosopher and curator Loïc Fel and with artists Claire Bardainne and Joanie Lemercier.

Bénédicte Ramade at Ambivalences #1 – Espace Tambour, Université Rennes 2. Photo: © Gwendal Le Flem / Association Electroni[k]

Bénédicte Ramade at Ambivalences #1 – Espace Tambour, Université Rennes 2. Photo: © Gwendal Le Flem / Association Electroni[k]

In her History of Ecological Art talk, art historian and curator Bénédicte Ramade explored the differences between ecological art, environmental art, green art, ecologist art, Anthropocene art, etc.

The word ecology, Ramade reminded us, was coined in 1866 by Ernst Haeckel. The German zoologist applied the term oekologie to the “relation of the animal both to its organic as well as its inorganic environment.” From this scientific origin, the term rapidly mutated and became synonymous with “environment” in the 1920s. It later took on a political dimension by becoming an “ecologism” in the sense of environmental politics, including the protection of nature. Over time, the word became almost synonymous with nature and lost some of its essence.

The 3 types of artistic practices Bénédicte Ramade presented are:

– ecological art practices with a focus on the scientific,

– ecologist art practices that have more social and political dimensions,

– and Anthropocene art practices that establish partnerships with the living.

The first category, ecological art, is anchored in science and in the ambition to solve pollution problems technically and tangibly. It is what Timothy Morton calls an ecology without nature, it’s a philosophical approach that sees nature as one of the possible territories of ecology but not as its exclusive breeding ground.

Dennis Oppenheim, Annual Rings, 1968

Not all artists engaging with nature can be regarded as ecological artists. Arte Povera artists, for example, use natural elements but do not claim any environmental position. The same goes for Land artists who have no desire for a scientific intervention on nature. They operate in the landscape, but without any environmental purpose, any intention to heal or repair any environmental malfunction.

Ecological artists have a much stronger connection with scientific research. They started working in the 1960s but it’s only in 1992 that they got their first collective exhibition, Fragile Ecologies, at the Queens Museum in New York.

Alan Sonfist, Becoming the Animal Within, 1972-73

The exhibition gathered artists who worked in urban settings and were interested in science. Alan Sonfist, for example, was looking into ethology in order to forge connections with the living, including the botanical.

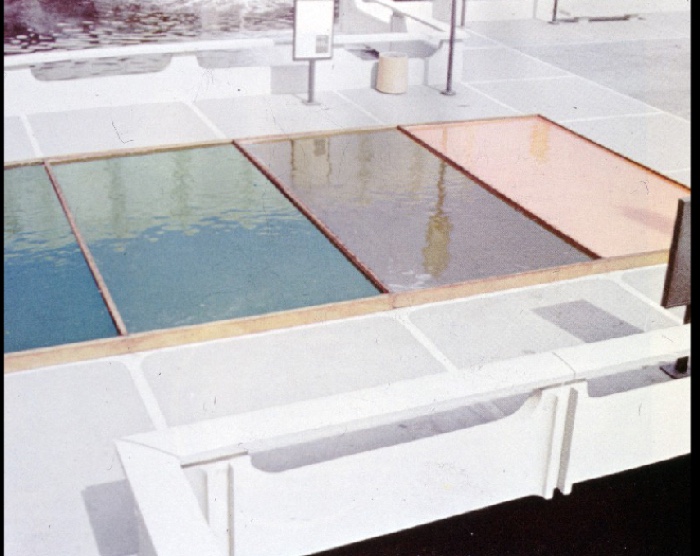

Helen and Newton Harrison, Survival Piece #2: Notations on the Ecosystem of Wester Salt Works (with inclusion of Brine Shrimp), 1971

Helen and Newton Harrison are other ecological artists. Their Survival Piece #2 consisted in a series of pools filled with water of different salinity, from seawater to brine ten times saltier than seawater. The Dunaliella salina, an alga that produces carotenoids as a response to increasing salinity, was introduced into each pond. Hence the different colours of the water in the pools. The artists then added brine shrimps which, as they were eating the algae, gradually depolluted the water and lowered its salinity. The work demonstrates the possibility of setting up filtration mechanisms that are totally ecological and based on scientific research.

Alan Sonfist, Time Landscape, 1965-1978

To rehabilitate an infertile piece of land in the north of New York SoHo, Alan Sonfist planted ancestral plants from NYC which he had identified in ancient documents dating back to the first colonisation wave. Having determined which trees and vegetation had been decimated by European colonisers, the artist grew a “time landscape”, a piece of lost nature that is still thriving today. Only non-human animals can enter the “precolonial forest.” Far from being some kind of Disneyland nature, the garden hosts rats, squirrels and other forms of wildlife that human neighbours might not like very much.

Patricia Johanson, Leonhardt Lagoon, Dallas, 1981-1985

Patricia Johanson was invited to Dallas to breathe new life into a badly degraded lake in the middle of the city. The water was murky and covered in algal bloom and the whole area was so polluted that barely any animal or vegetation lived there. Even the (human) inhabitants of the city avoided it. The artist used local and specially selected plants to activate various systems of water filtration and create microhabitats for wildlife. Big orange structures doubled as pathways for human visitors and refuges for frogs, turtles and marine wildlife. Today migratory species stop by to feed in this healthy environment. This is one of the earliest examples of art as bioremediation. Johanson collaborated with a variety of scientists, engineers, city planners and local citizen groups to ensure the success of the project.

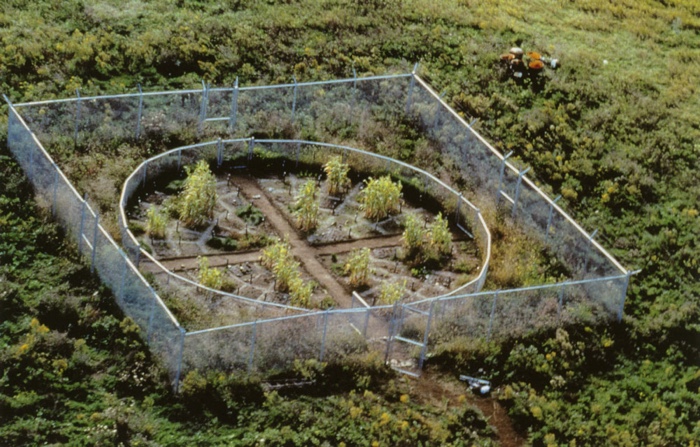

Mel Chin, Revival Field Pig’s Eye Landfill, 1990-1993, Saint Paul Minnesota

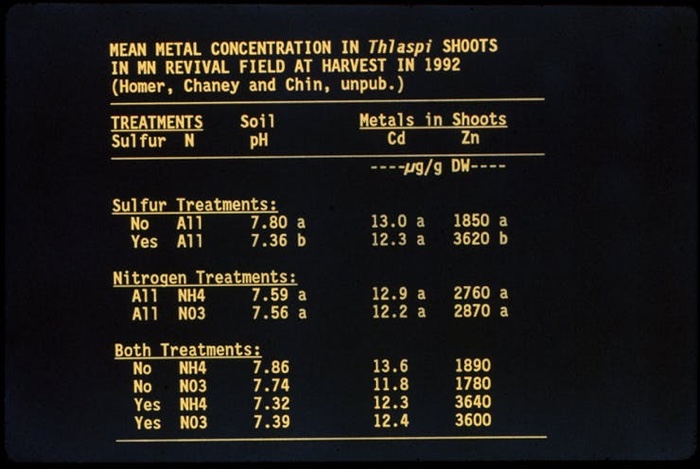

Revival Field results: amounts of zinc and cadmium absorbed by Thlaspi caerulescens

Mel Chin’s Revival Field Pig’s Eye Landfill never opened to the public. The work allowed scientists from a Texas University to develop and test out the effect of hyperaccumulator plants on very polluted soils, at Pig’s Eye Landfill, a State Superfund site in St. Paul, Minnesota. Scientific analysis of biomass samples from this field confirmed that six varieties of the hyperaccumulator plants could extract heavy metals from contaminated soil, proving thus the potential of “Green Remediation” as a low-tech alternative to costly remediation methods.

This scientific dimension characterises ecological art in the U.S. Aesthetics comes second. Chin’s work could not be seen by the public. Both Sonfist and Johanson’s parks look rather bleak in Winter. Which might explain why ecological art didn’t immediately capture the imagination of curators and audiences. The main objective of ecological art is not to please the public but to help ecosystems heal.

The next type of artistic practices Ramade presented belongs to “ecologist art”. More militant, more politically-engaged than ecological art, ecologist art is also more inclined to connect with the broad public of citizens. Previous works also tried to engage with the public but their main preoccupation was an ecological solution in the scientific sense, a knowledge-based rehabilitation of an environmental dysfunction.

Joe Hawley, Mel Henderson, Alfred Young, Oil, 20 September 1969. Performance event at the Standard Oil docks, Richmond, California. Photo: Robert Campbell / Chamois Moon

In 1969, Joe Hawley, Mel Henderson and Alfred Young drew the word “OIL” in biodegradable green dye in the San Francisco bay to call attention to a massive oil spill that had taken place a few months earlier along the Santa Barbara coast. The location of their action was the coast of Richmond, California, home to the Standard Oil refinery.

Nicolas Uriburu, Venice, Grand Canal, 1969

Nicolas Uriburu, Buenos Aires, 22 March 2010. Photo: Greenpeace / Martin Katz

That same year, Nicolas Uriburu embarked on a gondola and dyed Venice’s Grand Canal acid green, using a pigment that turns green when synthesised by water microorganisms. Concerned with environmental issues (and perhaps also by the art world’s indifference to them), his performance aimed at raising awareness about air and water pollution. Uriburu organised similar actions in Buenos Aires, Paris, Brussels, London and other locations. Sometimes even in collaboration with Greenpeace.

Gustav Metzger, Mobbile, 1970-2015. Centre Pompidou Metz

Gustav Metzger put plants and bits of meat inside a plexiglass box for one week. The only air they could breathe came from the exhaust fumes of a car. The work, first staged in 1970, reflects on the danger of a society that relies heavily on cars and fossil fuels. After one week, the plants inside the box were completely asphyxiated, a proof of the deleterious effect that air pollution has on living organisms.

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982. Photo: John McGrall

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982

Agnes Denes planted two-acre of wheat on a landfill at the feet of the Twin Towers in New York City. The terrain was estimated to be worth around 4,5 billion dollars. Her crops, however, earned her only 154 dollars in profit. The price of crops is fixed in Wall Street, physically located a mere block away from the field but billions of km away in terms of vision of world priorities. The work calls attention to the tensions between agricultural production and the estate value of land, between the world’s economy and the state of the Earth itself.

Tue Greenfort, Milk Heat, 2009, Wanas estate, Sweden. Photo: Anders Norrsell

Tue Greenfort excels at highlighting the contradictions at the heart of ecological promises. Invited to work at an organic farm that doubles as an art centre and sculpture park in Sweden, the artist quickly identified the energy cost necessary to produce organic milk.

At the time of milking, cows’ milk is 38°C, but the liquid needs to be cooled down to 4°C before it can be transported to the dairy. Greenfort realised that since Sweden is a cold country, the milk could be cooled at low energetic cost by having it go through a pipe system outside the barn.

The installation also shows how we heat up the environment through our consumption choices:

“The artist wants to highlight the effects of livestock on the environment, regardless of whether it is organic. He questions if dairy products can be seen as ecologically sustainable, when the methane emissions from cows result in a negative impact on the climate.”

Olafur Eliasson and Minik Rosing, Ice Watch, Place du Panthéon, Paris, 2015

A few years ago, Olafur Eliasson brought blocks of ice all the way from Greenland to a few European capitals at a huge environmental cost. The installation gave rise to heated debates around the CO2 cost of the transport of the ice to Paris which, even if it was compensated by the plantation of trees, remained jarring. On the other hand, one shouldn’t underestimate the emotional effect of being confronted with this ice. Not only were people crying in front of the ice knowing they were about to disappear but even museum institutions were challenged to intensify the conversation around the need to reduce the environmental impact of their cultural events. Maybe the level of awareness Ice Watch raised made up for its environmental price tag?

Now can we talk about “green art”? In his book on the green colour (the cover for the English edition of the essay is a bit off-putting but I can’t recommend Michel Pastoureau‘s books enough), Michel Pastoureau explains how the association of green with nature has mostly been a marketing invention. That’s one of the reasons why Ramade would rather talk about an “Anthropocene art”, an art that establishes partnerships with the living and recognises its agency.

Lois Weinberger, Cut, 37 meters, 1999. Innsbruck university

Lois Weinberger made a cut in the pavement of the campus of Innsbruck University. He then let the cut evolve by itself, trusting the living to continue the transformation. Soon, seeds brought by birds and wind, turned the long strip into a mini green garden.

Jérémy Gobé, Corail Artefact, 2019

A couple of years ago, Jérémy Gobé discovered a traditional lace pattern that is structurally similar to that of a coral skeleton. He worked with lace-makers to make organic cotton lace that will be used as potential support for coral development. The tests in the Pacific have been postponed due to the outbreak of the pandemic.

The work not only allies art, science and remediation, it also has the kind of aesthetic ambitions that were sometimes lacking in early ecological art.

Maria Thereza Alves and Gitta Gschwendtner, Seeds of Change: A Floating Ballast Seed Garden, 2012-2016, Bristol

Maria Thereza Alves and Gitta Gschwendtner worked on ballast flora, the plants brought to England in the stabilisation water and soil that were used to weigh down trading boats. Between 1680 and the early 1900s, ships entering the port of Bristol unloaded many tons of ballast along the river and the harbour. This ballast often contained seeds from where the ship had sailed. Some of these seeds are still found growing around Bristol today. Ballast flora are symbolic of the complexity of world history and, as Seeds of Change: A Floating Ballast Seed Garden demonstrates, they have the potential to challenge our definitions of “native landscape”. The work also raises questions about the point at which an ‘alien’ species becomes ‘native’, and how we determine our sense of national identity and belonging.

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, Sissel Tolaas and Gingko Bioworks, Digital reconstruction of the extinct Hibiscadelphus wilderianus Rock, on the southern slopes of Mount Haleakala, Maui, Hawaii, around the time of its last sighting in 1912 (Resurrecting the Sublime), 2019

I wrote about Resurrecting the Sublime a few weeks ago, in my review of the show Survival of the fittest. Nature and high-tech in contemporary art.

The next editions of Demain’s Conferences dedicated to the issue of environmental change will take place in Caen (April 2021) and in Nantes (September 2021). A collaboration between Stereolux, Oblique/s and Electroni[k].