Emma Dorothy Conley is an artist, designer and also a producer at the Center For Genomic Gastronomy. Concerned by newspaper stories about the microbiome and how we shed bits of it wherever we go, she decided to investigate the future of microbiome privacy.

The microbiome is a unique collection or community of microbes that live inside and outside our bodies (and pretty much everywhere else on our planet.) Your own microbiome functions as a record that reveals information about the people you’ve met, the places you’ve been to and the food you’ve eaten. In the future, microbial residues collected at crime scene could even help track down criminals. “All you need is an extensive database than currently exists,” explains Jack Gilbert, a microbiologist at Argonne National Laboratory.

Of course, the idea that the microscopic organisms that cover our body might one day be used to identify us raises a series of privacy and ethical concerns. The Microbiome Security Agency proposes to create a toolkit of DIY biological information manipulation tactics that would enable us to protect and secure our own data.

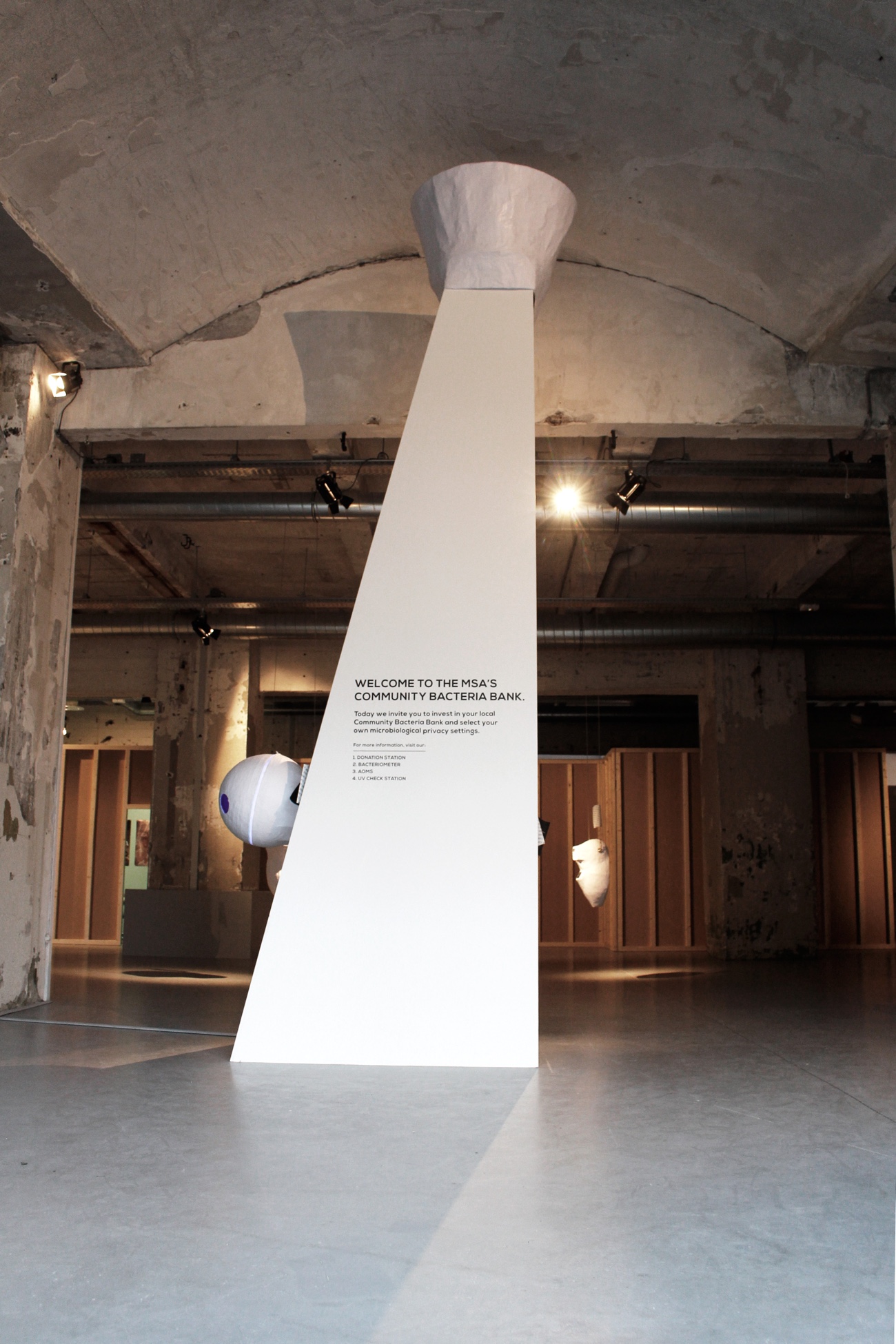

The Microbiome Security Agency (The MSA) investigates the future of microbiome privacy issues and prepares citizens for a future where our personal information is at risk through our biological datasets.

The MSA is one of the winning works of this year’s edition of the Bio Art & Design Award. The international competition invites young artists and designers to collaborate with Dutch science centers in order to develop thought-provoking art and design projects that engage directly with life sciences. The winning projects are currently part of Body of Matter, an exhibition that interrogates our ideas about the body.

The website of the MSA is packed with super useful and interesting information but i still wanted to ask Emma a few questions about the work:

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

Hi Emma! What inspired you to work on the Microbiome Security Agency? Did you read any news stories related to the human microbiota and loss of privacy, for example?

Microbiome research is quite prevalent in popular science news, so over the last few years I’ve

been seeing lots of articles every week about emerging research in the field. There were lots of articles that discussed the uniqueness of an individual’s composition of bacteria, however I never found anyone pointing exactly to emerging privacy issues. It seemed like a gap in the conversation that needed to be investigated farther.

People love to read and talk about poop, so pieces on the topic of fecal transplants were constantly popping up, and being shared and debated online. In fecal transplantation for medical purposes, the donor has a healthy composition of gut bacteria, while the recipient doesn’t. We know our compositions of gut bacteria are fairly unique to us, so I started to wonder, what does it mean to give away or take on elements of someone else’s microbiome?

Investigating this idea of ”uniqueness,” I started looking up different papers on the subject and different research groups that take bacteria samples from the general public in exchange for a report of their microbial makeup. I thought maybe I’d send in a fecal sample and see what my composition looked like and how it changed over time. While reading the marketing material from these microbiome research groups, I started to seriously question the collection and databasing processes that these groups use. The company UBiome, for example, advertises, “Sequence your microbiome through citizen science!”

In exchange for a payment and sending in your fecal sample, along with loads of personal information about your daily habits, diet, and demographics, you receive a report of your microbial composition, with little to no actionable information. Is this citizen science? And what do they do with all of this personal information—and personal biological information? That’s where the project began.

Can you tell us about the MSA DIY toolkit? Which kind of tactics will it provide citizens with? And how affordable and easy to use will it be for everyone?

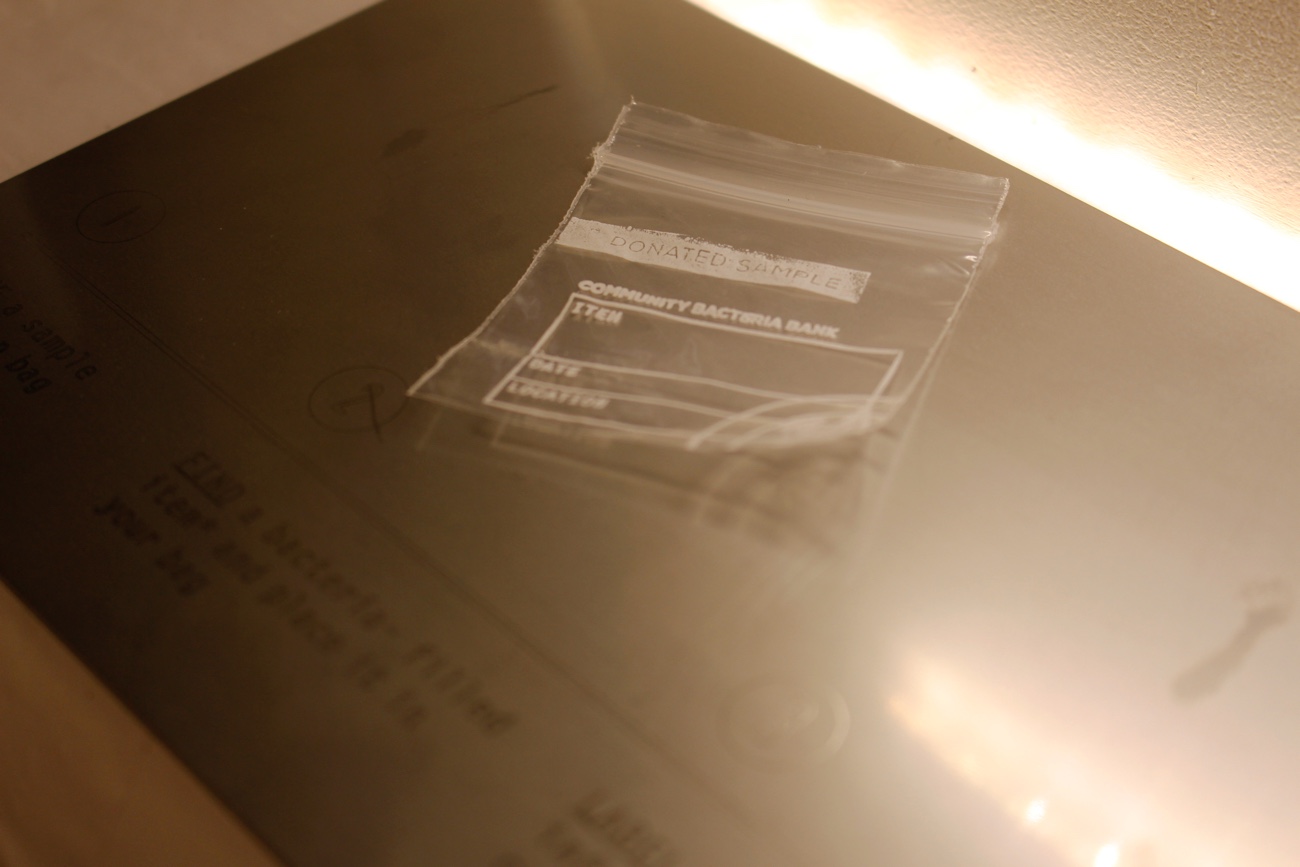

We set out to find a do-it-yourself means for manipulating your microbiome in an effort to protect the information it might reveal. This is very tricky. For many health reasons, you really don’t want to change a healthy microbiome very much. Your bacteria help in lots of important bodily processes. It’s widely thought, for example, that the overuse of antibiotics has led to many current health issues plaguing the western world. So, instead of a toolkit for DIY microbiome manipulation, we created a system that asks citizens to support each other by investing in their microbiological privacy together. The MSA created a Community Bacteria Bank. Individuals invest in the bank by donating bacteria-rich samples (pretty much anything). These samples are processed into an “obscuration solution” to be applied to the skin—anonymizing the pre-existing bacteria. The Community Bacteria Bank functions as a working prototype, testing out one possible future scenario or system, along with products and processes, for securing our microbiological data.

Leading up to the creation of the bank, we decided to organize the project into two research

categories: destroying and obscuring. Destroying eliminates important information, while obscuring adds noise and anonymizes important information.

In our destroying experiments we treated fecal samples with household cleaning products, attempting to eliminate the traces of DNA of the bacteria from these samples. Three people donated six fecal samples each, which were treated with:

1. Microwaving

2. Alcohol

3. Peroxide

4. Aceton

5. Ammonia

6. Bleach

Eliminating the DNA would mean that the bacteria would be unidentifiable. We found that it was actually quite difficult to destroy all the DNA from these samples. It was often lessened by the cleaning product, but in equal parts, so the composition was still clear. Peroxide was the most successful, so if you need to destroy a fecal sample in a hurry, it’s your best bet.

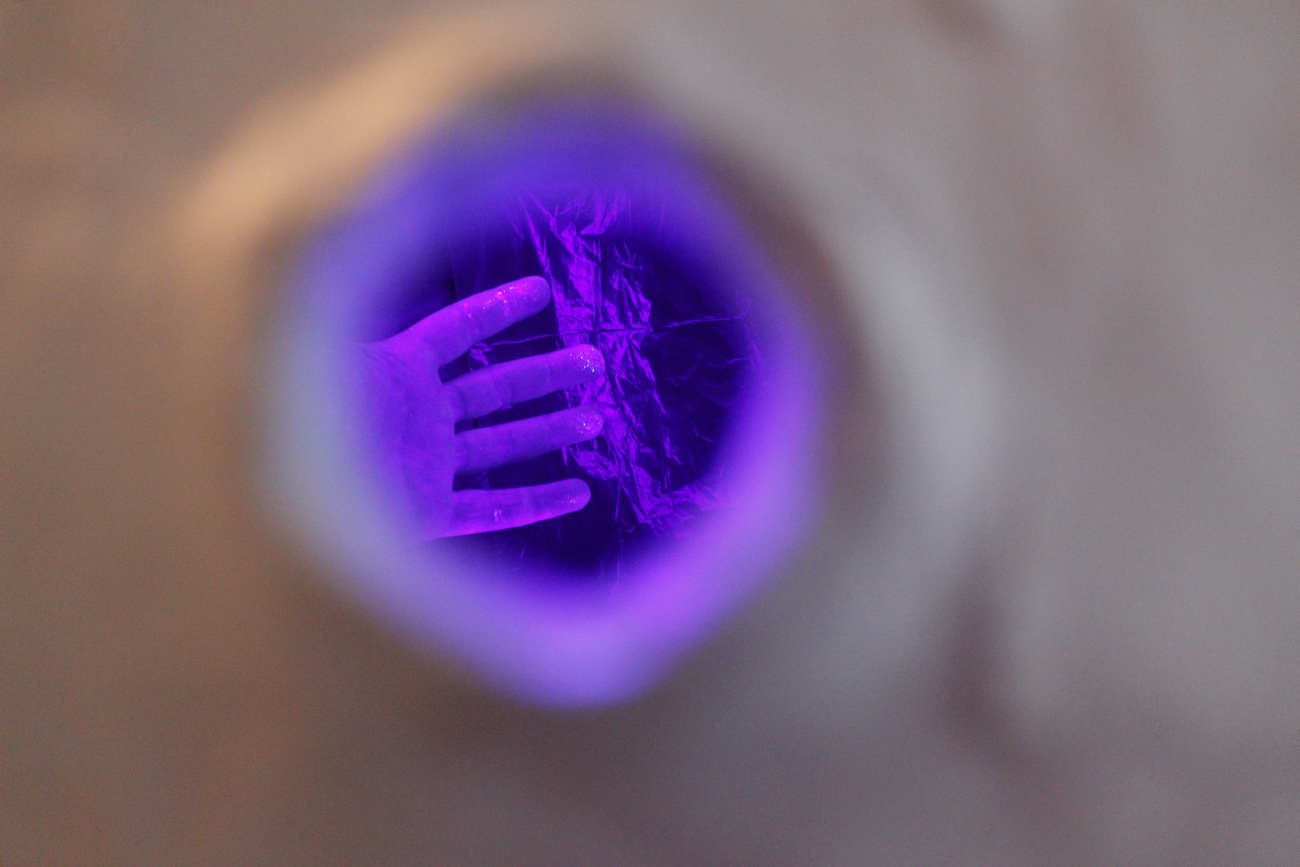

From there we moved on to obscuring the DNA of skin bacteria, which turned out to be a much more successful approach. In this experiment, we wanted to create an “Obscuration Solution” that could be applied to the skin microbiome to add noise and make your own bacteria unidentifiable. We wanted to create a bizarre, fake microbiome that would hide your own.

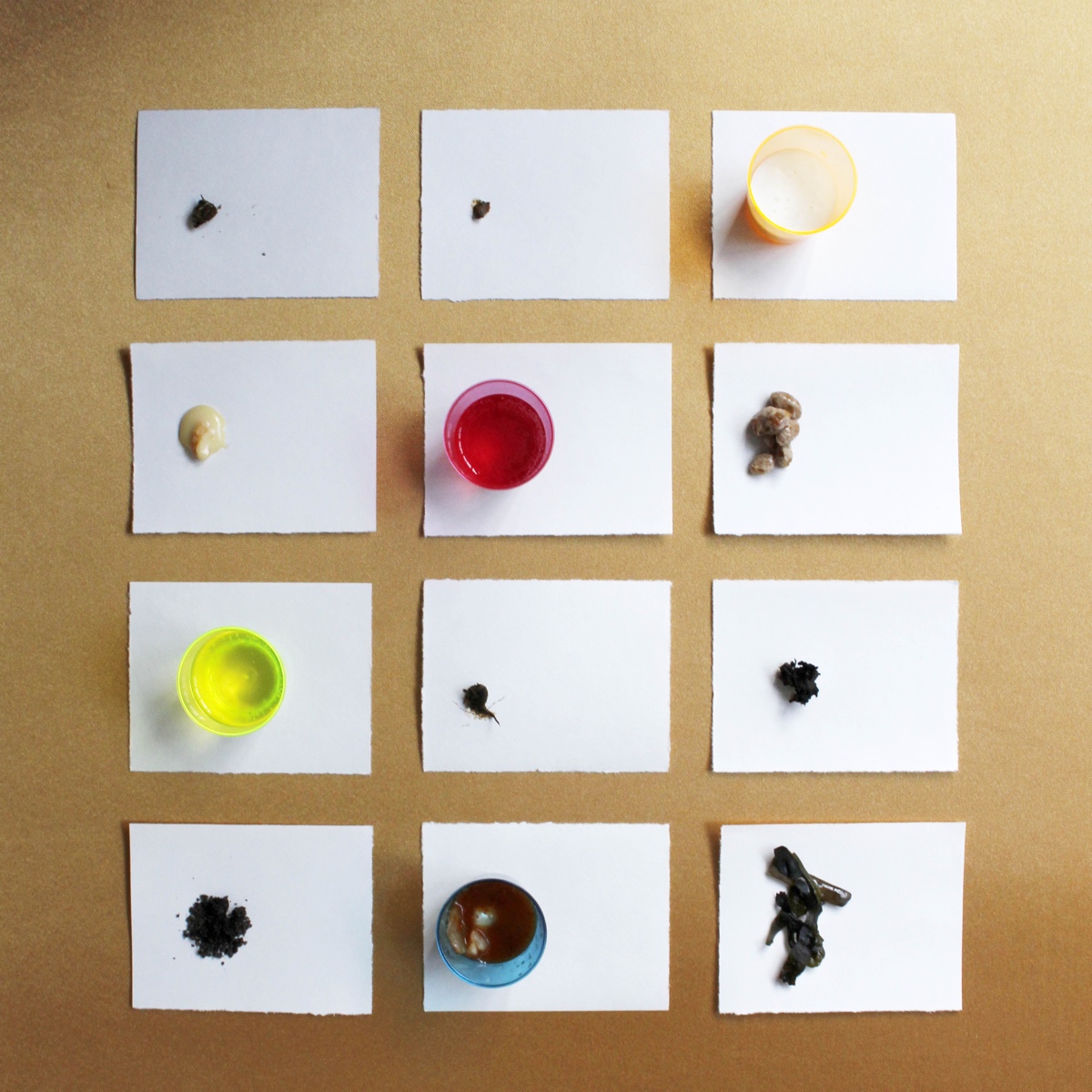

To do this, we collected samples of bacteria-rich items from all over and blended them together. We randomly selected different foods, feces, soils, etc. containing what we knew would be a diverse selection of microorganisms:

> red ruffed lemur feces

> greater rhea feces

> white-faced saki feces

> kefir

> epoisse cheese

> kombucha 1

> kombucha 2

> natto

> compost

> kimchi

> soil

> seaweed

Samples of the blended mix were sent to the lab and the DNA from the bacteria was sequenced and amplified, resulting in a synthetic DNA mix resembling a completely new and unique ecosystem of bacteria. This DNA solution was placed in different mediums that could be applied to the skin: a powder, a mist, and a gel.

What’s with the fecal sampling? Why would people try to collect fecal matter at the zoo? and why the zoo, why not from our pets? or from a public park?

Pets, parks, zoo animals, everything is good! The beautiful thing about bacteria is that they are just about everywhere. We collected fecal samples from a zoo for two reasons: the gut microbiome contains a diverse selection of bacteria, so you get a dense, varied assortment in just a small fecal sample. Gut bacteria compositions also change based on what we eat and where we live, so stool samples from exotic zoo animals can add a lot of diversity to the blended mix.

What were the biggest challenges you encountered while developing the project?

In terms of the research, one challenge was performing a difficult experiment in tracking and tracing the changes of the skin microbiome over time. Could we begin to put stories together about where someone has been and who they’ve been around by comparing their makeup of bacteria to those people and places? We tried sampling the skin microbiome as well as different environments by using tape to grab bacteria off different surfaces. We haven’t been successful in proving or disproving traceability yet, but I think it is very important research and I hope there is a lab or research group interested in doing a full study.

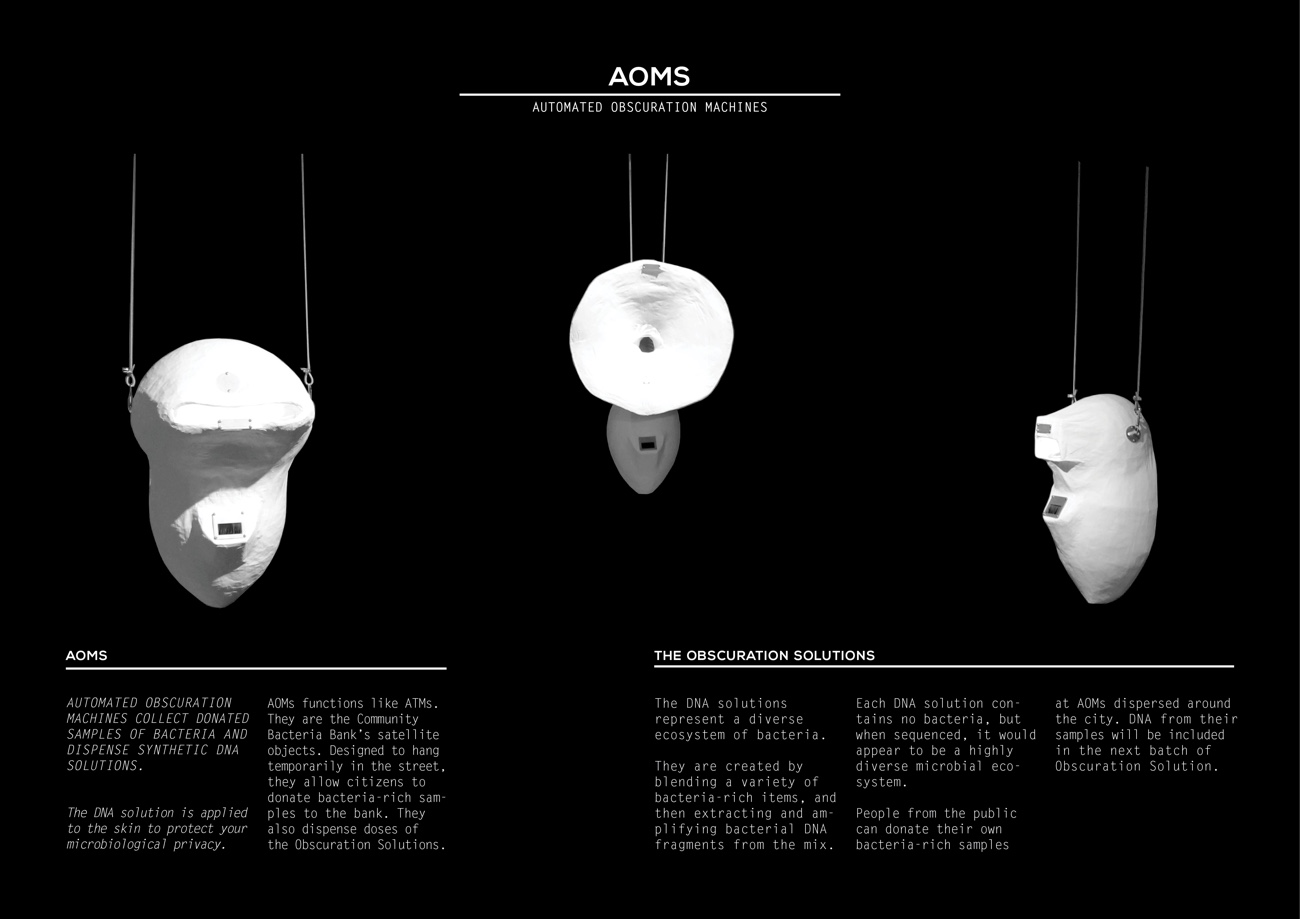

Bacteria Bank. How It Work: AOMs

In terms of the project, realizing that a DIY solution was not (and rarely is) as good as a do-it-together solution was one of the biggest challenges and revelations. We wanted to design something that empowered individual’s to help themselves and to help each other. We wanted to find a clever solution that loudly out-smarted an unfavorable system, rather than encouraging others to silently hide in the shadows of that system. The Community Bacteria Bank was designed to do this. It houses the diverse bacteria samples donated by the public, but it also includes satellite-objects, called AOMs, that function like ATMs. These AOMs are designed to be temporary receptacles on the street. Citizens can donate a small bacteria-rich sample at an AOM, but they can also received a dose of the “Obscuration Solution” in the form of a mist, powder or gel. When applied to the skin, this “Obscuration Solution” adds a layer of DNA (not bacteria, just DNA) that obscures the bacteria on the user’s skin. The idea is that if we all donate samples to the mix, it becomes very diverse and adds a lot of noise to the Obscuration Solutions. If we all use the same Obscuration Solutions, our skin microbiomes will all look the same and our microbiological information will be secure.

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

I’m also curious about your collaboration with Guus Roeselers and his research team. How hands-on did you manage to be with the scientific protocols and process? Were you allowed to get inside the labs and work along with the scientists?

I was very lucky to work with Dr. Guus Roeselers. In addition to being extremely knowledgeable in regards to the science, he is incredibly creative and interested in important cultural and ethical questions. He was always willing to imagine and explore different futures scenarios, regardless of whether they were controversial or even likely. For many reasons, it was not possible for me to work in the lab at TNO. In some ways, this was very fitting given the idea of the project. I prepared many of the samples at my home or in my studio: an average citizen, creating an “Obscuration Solution” to protect the average citizen. The samples were processed and sequenced and the DNA was amplified by technicians in the lab, but Guus and I designed and executed all other aspects using effective and safe at-home practices.

The masks and outfits you were on the homepage of the project are quite striking. Can you tell us something about them?

The MSA has agents who run the organization. They help in collecting bacteria-rich samples, and also manage the AOMs and maintain the bank. They show citizens how to collect and donate samples and explain how the Obscuration Solutions work. MSA Agents wear shimmering, colorful uniforms and large white masks to protect their faces and protect their samples and solutions. The uniforms are designed to be bold and noticeable to reinforce the idea that this is a project about empowerment, inspiration and fun, rather than fearfulness.

Our goal is to create more options for individuals, to test out possible futures, and to challenge the notion that we should fear those with power rather than be empowered ourselves. The MSA is interested in a proactive approach to building a future we want to inhabit, by creating options to work with,in a complex world filled with unknowns and promise.

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency, Body of Matter, Installation view, MU, Eindhoven. Photo courtesy of the artist

Thanks Emma!

MSA: Microbiome Security Agency is part of Body of Matter. Body based bio art & design which opens at MU in Eindhoven on 27 November. The show will be running until 7 February 2016. Also part of the exhibition: The Art of Deception by Isaac Monté and Drones with Desires.

Related story: Matter of Life. Growing new Bio Art & Design.