Tears have a fairly complex composition. They contain water, of course, but also electrolytes (hence the saltiness), lipids and proteins. That liquid is pretty useful. It lubricates and protects the cornea of the eye, removes irritants and helps focus light so you can see clearly. Tears also contribute to protecting the immune system.

But can tears have any use outside of our own human body? Could they be “harvested” and used in a way that would connect us more intimately with the living world?

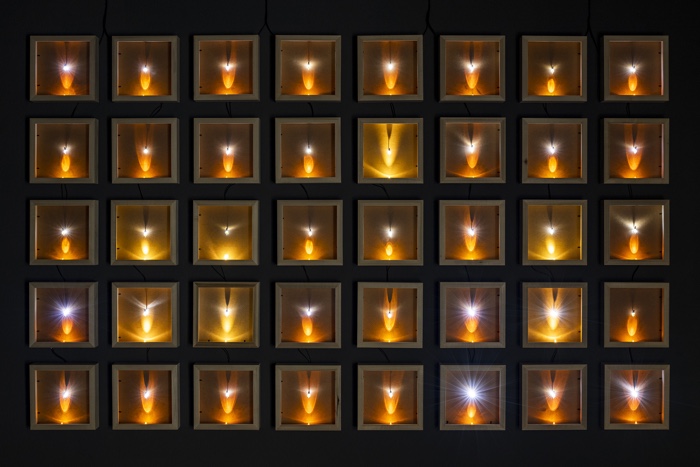

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Gosia Siwiec

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Falk Wenzel

In Autumn 2019, Kasia Molga experienced the loss of loved ones. She shed so many tears that she decided to collect them in a small container. The pandemic, along with the already present anxieties about the environmental meltdown, only increased her sense of unease.

“With so many tears I started to wonder whether it is possible to cultivate some marine life in them,” the designer and artist writes. “To make something life-affirming was my way to deal with this devastating loss – not only personal or caused by pandemic, but also environmental.”

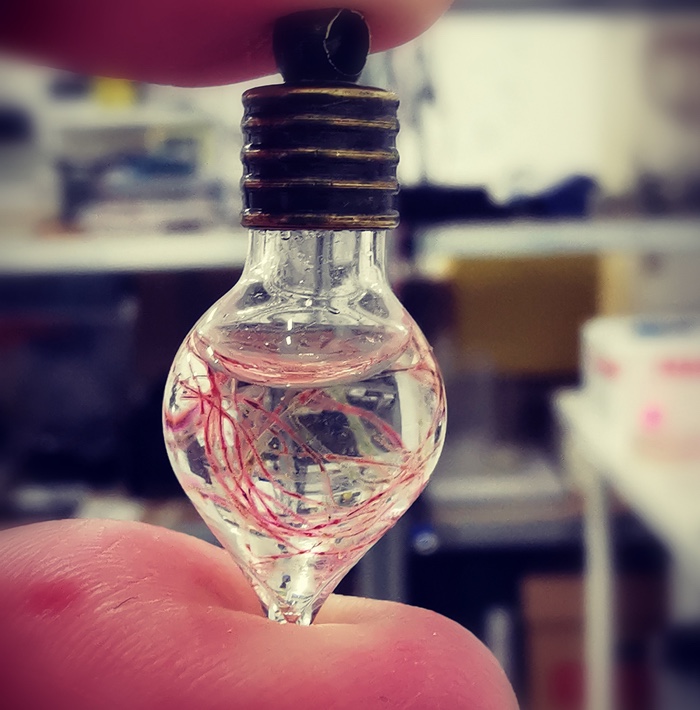

Molga soon started collecting her tears and designing a series of spoons, glass containers and other objects that made the operation easier. She then experimented with growing algae inside the tiny tears containers. The result is How to Make an Ocean, an installation that allows the audience to look at the collection of tears and life present in them. Participants, with help of the AI Moirologist Bot, are also invited to contribute to the growth of my mini-oceans by adding their own tears to the collection.

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Falk Wenzel

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean

I discovered How to Make an Ocean while visiting one of the ISEA2022 exhibitions at the arts center Santa Mònica in Barcelona. I recently emailed the artist to get more details and background about the project:

Hi Kasia! Your work made me wonder about the cultural dimension of tears. Your text mentions the Japanese crying therapy called rui-katsu and the figure of the moirologists whose job consisted in crying and helping others cry at funerals and wakes. In contemporary Western culture, do tears still have a role and significance? Tears tend to be something you have to hide, something that is “too feminine”. For example, I cry very easily and mostly when I’m happy for someone else. I find it embarrassing and difficult to justify when caught in the act.

Tears are involuntary and, apparently, only humans cry out of emotions. So, in my opinion, whether we (in Western culture) want it or not – they always will be present and are significant. Just think about how many people you know who never cry? I guess there are individual cases who cannot cry, but not many. When I was researching tears for How to Make an Ocean, I learnt that mostly we cried when we felt powerless. Perhaps that is the reason why the act of crying to so many of us is “embarrassing” and shouldn’t be on display – a very primal instinct not to show any vulnerability – regardless of the reason for the tears.

On the other hand, some research has argued that it is very beneficial to cry – because not only does it help people relieve some of the emotions, but most importantly gets rid of toxins produced in our bodies when under stress. Darwin was fascinated by tears and had a theory that although it is firstly a reaction to an obstruction of the tear duct or irritation of an eye, we humans evolved further and the inability of expressing some of the feelings was “perceived” by the brain or the nervous system as obstructions too – hence tears as a reaction to sadness, anger or pain. So excess toxins such as adrenaline or cortisol can be thought of as irritations which have to be cleared.

Moirologists were people who, in my opinion, in a way were demystifying crying out of sadness and grief – thus helping others to “let themselves go” and cry and get rid of the toxins, find some clarity and embrace loss.

Coming back to western culture nowadays – through the research I made I found that it is true that tears are not very present in the wider public domain. But for example, there are methods of creating a narrative to make people shed tears, to evoke empathy. This is used in advertisements very often. Or in animated movies. PIXAR is a master at creating vignettes, playing with how scenes are framed, lightened and animated and the sound is composed, to make it as “tear-jerking” as possible.

And I think with so much uncertainty and anxiety which has been around for the last few years, we need to allow ourselves to cry and not be embarrassed. We should actively keep creating spaces where we can hold our grief or anxiety and encourage ourselves to cry. We connect through the act of crying in a very empathic way. Just like with good, friendly laughter.

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Falk Wenzel

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Falk Wenzel

One of the initial objectives of the project was to investigate the chemical and physical properties of human tears and what marine species they could support. What have you discovered? Can tears sustain any form of marine life?

What does a tear contain exactly and does it differ from one person to another depending on their health or what they’ve eaten that day?

The tears contain some waste from our organisms – protein and hormones which differ depending on the reason for crying. But naturally, the most basic ingredient is H2O. I find it miraculous that our human body can make water out of, well, emotions (in a semi – metaphorical sense, biology, chemistry and physics are much more complex). I have talked a lot in my work about growing up on the open ocean and my love towards seas, so although the grief was a catalyst, to look at water produced by me as a possible ingredient of the future mini marine ecosystem was a logical progression. I wondered whether that water full of my hormones and other human substances would have any sort of influence on the growth of algae.

One day I placed in my tears a really beautiful, vivid pink algae from the North Sea called Callophyllis laciniata. To my despair, it lost its beautiful red colour and became very pale. I found out that one of the reasons for their vivid colour is beta-carotene, so I started to eat more carrots to see whether that has any influence. I must add here that my “research” is inconclusive as some algae lost their colour and some not, but it started a new line of inquiry in my work – how to look after my own body to “serve” marine ecosystems?

Unfortunately, while I was researching for How to Make an Ocean, we were in the middle of the pandemic so any access to biolabs was impossible. But now I would love to continue it and I have already started a new body of work “How to Become Wholesome?” where I use various bodily waste for setting up my small marine ecosystem.

Coming back to the question of whether tears can sustain any forms of marine life: the water in seas and oceans are in perpetual movement and contain certain elements / minerals needed to sustain various organisms and food chains. So naturally, it is an incredibly complex and delicate system. Marine aquariums have pumps which filter water (needed in such small containers) and make it flow, so that this very simplified ecosystem can be managed by humans – either for pure aesthetic pleasures, conservation or marine biology research. I used professional marine aquarium equipment in “How to Become Wholesome”.

But How to Make an Ocean is made out of tiny containers with static water, so as such at the moment it resembles more of a pond water. However human teardrop dries quite fast (it is quite thick), so in order to “preserve it” I mixed it with a drop of sea water – which also then provides some basic nutrients for algae. Algae of the North Sea are not so demanding (perhaps except the aforementioned red algae), and so far they seem very happy in those small containers – some of them even grew.

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean

What impact did this project have on your grief? Did it interfere with it? Prolong it? Turn it into a kind of habit and “job”? Or did it help provide some catharsis or distance from the pain?

This project helped me to really embrace grief and come to terms not so much with the loss, but with my own emotions surrounding the loss. It was cathartic – allowing myself to very consciously and slowly go through the pain. It also gave me the courage to talk publicly about grief and my own anxiety and the importance of sharing such experiences publicly – all of which was quite empowering. Naturally not everyone wants to do that – grief can be very private, but in times of great extinction, environmental anxiety and loss, it is important to create a space for such emotions.

It never became a “job”. However, I worried that when my tears dry up, I would be left with nothing to feed my mini-oceans. And so I started looking into ways to make myself cry. Which was very interesting research on its own – what sort of audio/visual stimuli are the most tear-inducing? I guess it can be summed up as creating an audio-visual narrative which evokes a deep sense of empathy – as I mentioned before Pixar mastered that in their animated movies – through storyline, music, image composition and colour, lighting, character expressions or camera movement. Of course one of the most powerful prompts is the real stories and other people crying.

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean – Performance (fragment of the audio-visual performance), 2021

Kasia Molga, Moirologist Bot

It is highly unusual to invite people to cry at an art exhibition. You can shock, amuse, surprise an audience but asking them to cry and reflect on their own pain is not something I’ve encountered very often. Do you know if people were seduced or maybe upset by this appeal to share a moment of intimacy in a cultural setting? And how did you make sure that they would be comfortable enough to engage with your invitation to cry and donate their tears?

I was quite self-conscious when I decided to make the whole set-up “participatory”. But I realised the invitation to cry was the best method to engage visitors and therefore help to understand the connection between their tears and oceans; and how the digital realm comes into this equation with its huge impact on our psyche – hence the AI Moirologist Bot.

The most important thing was to make a space where a visitor could be alone and feel intimacy, hence the cinema room for one person only, with the 15 minutes intervals of Moirologist’ screening. In a manned setting, there are tearspoons and bottles available to capture tears. Frankly, I don’t know if during the expositions anyone has cried, although I have been told on a few occasions that the whole display moved a few people so strongly they did shed some tears.

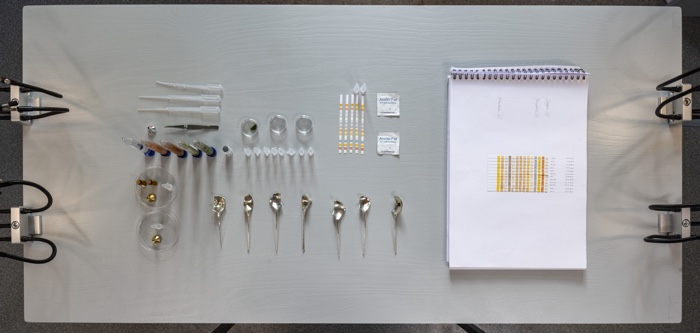

But in 2021 I was invited to make a How to Make an Ocean workshop performance by Jasmin Grim – an artistic director of the New Now Festival in Essen. Together with the New Now Festival team, we designed a setting so that around 10 to 12 people, even if together in the same room, could feel safe and intimate enough to let themselves cry. Each participant had one mini-ocean tool set – with tearspoons, algae, seawater, pipettes, tiny bottles, etc. Each person also had headphones – so I hope it felt like my and Moirologist Bot voices guided everyone individually. And naturally, the light was very dimmed. To my surprise and delight, quite a few people shed some tears. Some participants told me that they really needed such a session – slow and in a way relaxing – to let them embrace their anxieties, anger, loss or whatever else they were dealing with. But the audience came to this workshop-performance expecting that to happen. The weirdest thing however was that there was also an audience – people who didn’t take an active part in this. But participants didn’t mind it and the audience sat quietly, seemingly captivated.

It feels weird to say that I am happy that it was “successful” – I made people cry. But those tears were for a good purpose. And some of them became a part of How to Make an Ocean display.

Kasia Molga, How to Make an Ocean. Photo: Malgorzata Siwiec

Can you tell us something about the visual identity of the installation? The display you use to showcase the bottles and the spoons modified to collect tears? How did you balance the scientific and the intimate elements of the work?

When one is passionate about something, however, scientific work might be, it will always be at least a little bit intimate. There will be a very personal relationship to the subject, and care to conduct the research in the best possible way. That is what I gathered from conversations with a few scientist friends. They were so deeply invested emotionally (as well as intellectually) in their tiny colonies of bacteria, or slime mould or baby corals.

I found it very difficult to stay unbiased. Because I wanted my grief so badly to be turned into something positive and in a way life-affirming. I wanted to see not only algae thriving in my tearst but also copepods, shrimps or rotifers – which are extremely important elements of the ecosystem. And I wanted them to do well! My marine biologist friend – Seb Prejsner from The DEEP in Hull kept me grounded – we were discussing the ethics of keeping tiny species in tiny containers, salt balance or other nutrients, while questioning whether we have rights to decide that some organism is “happy” or not based only on its physical wellbeing.

The tearspoons as I called them were created from pure need. I found that it was not easy to capture tiny teardrops. Lab sample bottles, normal spoons or pipettes didn’t really work. I studied the shapes of old lachrymatory bottles and some of them had a kind of tiny basin on top shaped in such a way so that one could place it against the cheek. That inspired me to create special tools – easy to handle, which wouldn’t let anything spill and can easily transmit the tear to a container. It is made out of silver – apparently silver possesses antibacterial qualities and it was important to me to preserve the purity of tears. I wanted to make sure that it didn’t look like a lab tool – because of the intimacy of an act of crying.

A lot of scientific work happened before – and tearspoons are the result of it. So are the tiny glass containers. Having the ambition to make an ocean at the start I didn’t realise that crying produces such a small amount of liquid. In order to collect 0.5 litres, I would have to cry non stop for months. Some tears were “donated” by friends and I wanted to preserve the tears’ individuality. The tiny bottle was a natural solution.

Each teardrop holds the memory of someone or something, and by mixing it with a drop of seawater and enclosing it in a tiny container I wanted to preserve this memory and give it the power to sustain a new life.

You discovered that the way your social media news feeds are curated by algorithms has a huge impact on your mental wellbeing. Did you take any measures to stop social media from interfering with your mental well-being?

I certainly limited my “intake” – both social media scrolling and reading the news first thing in the morning. But in terms of social media I am not really a good user – posting extremely occasionally on FB and Twitter, being more active on Instagram which I use as a sort of visual record/research for my work.

But it doesn’t matter how much I limit myself. People around me – sometimes those closest to me aka family members are exposed to so much negative information or fake news and, especially in the case of elederly relatives, often they don’t have the tools to deal with it. That has the spillover effect – regardless of how super tech savvy I might be, the anxiety is there because I am running out of ideas on how to protect them (the elderly rarely want to learn from younger ones). So social media still affects my mental health – indirectly maybe, but very effectively.

How can art and creativity, in general, contribute to the issue of the environmental crisis?

In so many ways – but I feel that whatever I type here will be a repetition of what greater and wiser than me had said. From a personal perspective, I can only add that for me the most important thing is a compelling narrative – a story-telling via various media which can be accessed by audiences outside the regular peer network (media / tech art, critical design, academics). Those narratives for me are about revealing those frail and almost unnoticeable but vital inherent interconnections between us (humans and non-humans), hopefully inducing deeper understanding, wonder, empathy and care. “Care” is the main keyword here.

Thanks Kasia!