Invisible Colors. The Arts of the Atomic Age, by Gabrielle Decamous, Associate Professor in the Faculty of Languages and Cultures at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan.

Publisher MIT Press describes the book: The effects of radiation are invisible, but art can make it and its effects visible. Artwork created in response to the events of the nuclear era allow us to see them in a different way. In Invisible Colors, Gabrielle Decamous explores the atomic age from the perspective of the arts, investigating atomic-related art inspired by the work of Marie Curie, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the disaster at Fukushima, and other episodes in nuclear history.

[…]

Emphasizing art by artists who were present at these nuclear events—the “global Hibakusha”—rather than those reacting at a distance, Decamous puts Eastern and Western art in dialogue, analyzing the aesthetics and the ethics of nuclear representation.

Shiga Lieko, Child’s Play, 2012

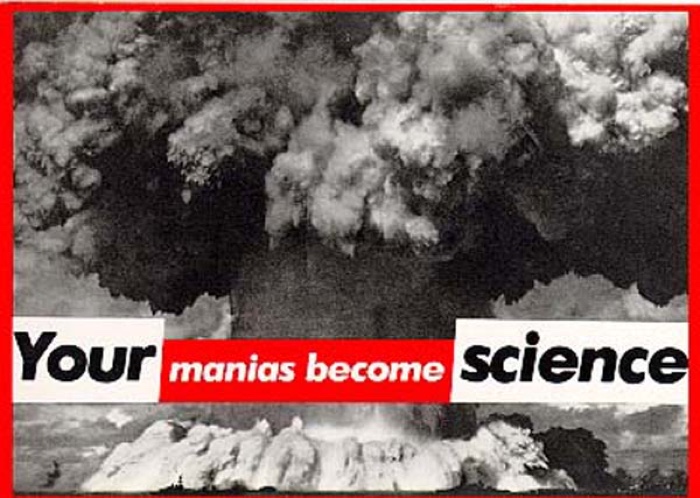

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Your manias become science) , 1981

Homma Takashi, Mushrooms from the Forest, 2011

Invisible Colors explores how artists make palpable the imperceptible, the intangible, the unthinkable. The catastrophic accidents, the lethal weapons, the impoverishment of ecosystems, but also the invisible ‘everyday’ radioactivity.

Gabrielle Decamous’ book is not the first publication about art and the nuclear but it expands the observation field to artworks and perspectives that the West has often neglected. The scope of her investigation is vast in terms of the geography, time frame and creative disciplines examined.

In terms of geography, the analysis is looking both East and West. With Chernobyl, Fukushima, Nagasaki and Hiroshima of course. With the Three Mile Island accident and the nuclear tests in the Pacific and in Nevada. But the author also looks at regions across the world that have been affected by the nuclear and yet remain under the radar. The Namibian communities living around the Rössing open pit mine, for example, don’t get much attention nor compensation for the high cost their bodies and environment pay to ensure that the West has access to the dangerous mineral resource. Or the people living in the South Pacific islands where the French carried out nuclear tests they insisted were “clean” in the 1960s and 1970s. That’s when you realize how much the colonial legacy endures into our complex globalized world.

Critical Art Ensemble, Radiation Burn, 2010

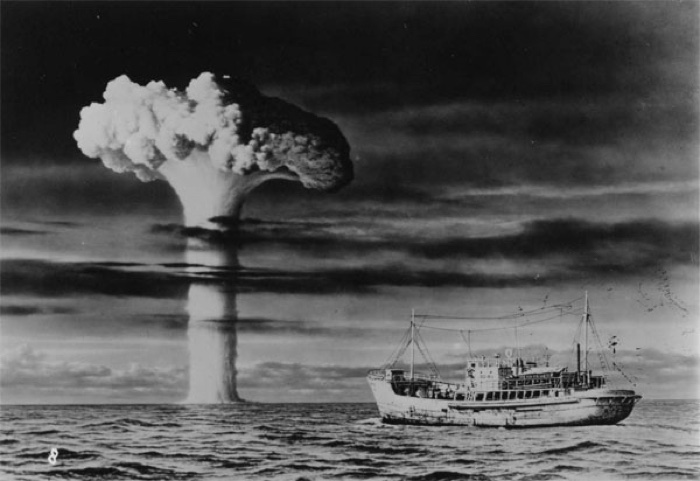

Kaneto Shindo, Lucky Dragon No. 5, 1959

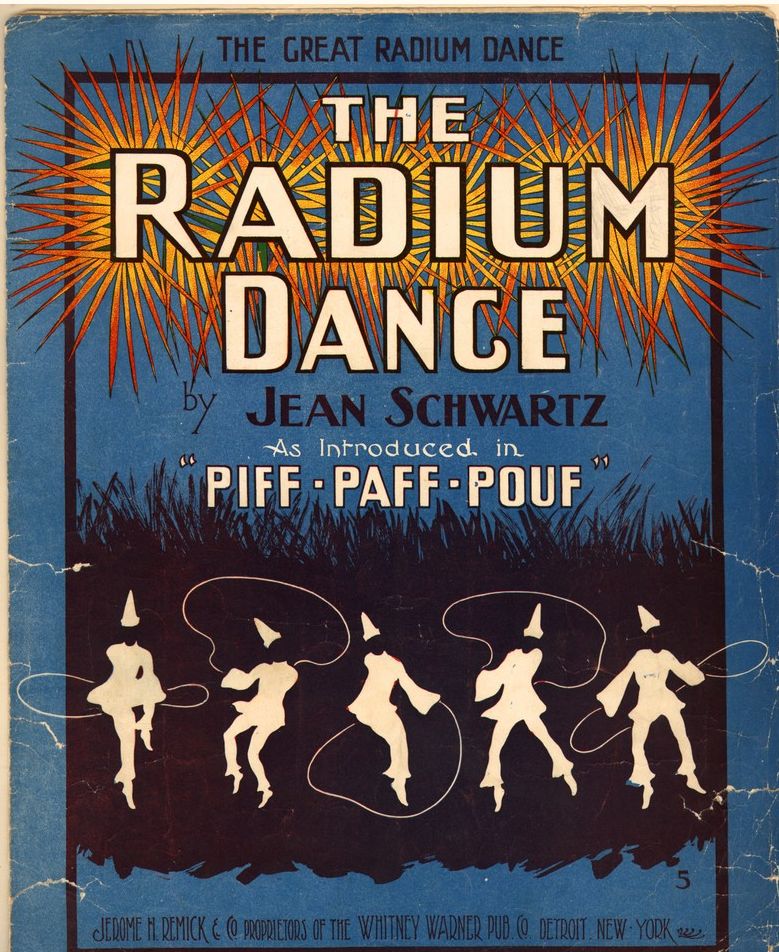

Jean Schwartz, The Radium Dance, part of the W.C Whitney production Piff!, Paff!, Pouf! in 1904

The chronology Decamous considers is equally comprehensive. It brings in works from the time of Marie Curie’s discovery of radium up until the aftermath of Fukushima. I was particularly fascinated by the work of Movimento Nucleare, an artistic movement founded in Milan in 1951 with the objective to create works that respond to the atomic age, often with a clear political, antinuclear message. The broad historical perspective is a particularly precious one because, as the author explains, the West tends to look mostly towards the future at the expense of a deep reflection around past mistakes.

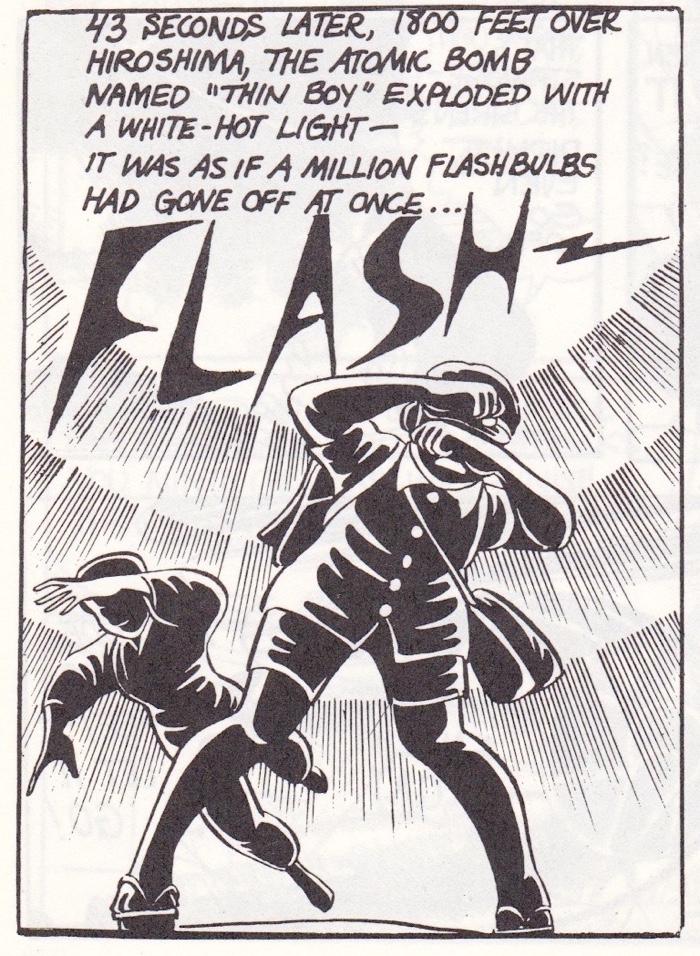

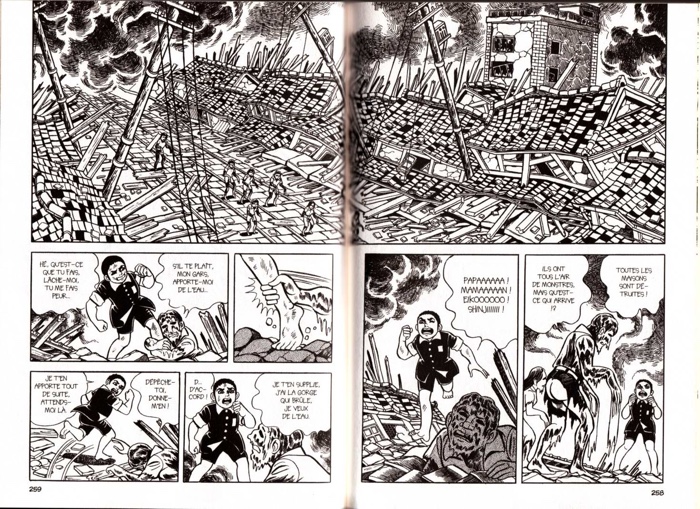

I associated representation of the atomic age with visual arts. Fortunately, Decamous isn’t as parochial as i am. Her book thus explores how other art forms such as the performing arts and music (with Iron Maiden, Sun Ra, even The Stranglers!) are keeping the discussion around the atomic age alive. Literature seems to have been particularly responsive to the discovery of radium, going from adventure novels haunted by the fear of evil men stealing radium to more doomsday narratives that reflect a growing awareness of radium’s harmful effects. There was scifi novels, A-bomb books but also poetry and mangas, most notably Barefoot Gen, a series loosely based on Nakazawa Keiji’s own experiences as a Hiroshima survivor. Decamous even uncovered the existence of a cookbook! In 1965 and 1970, two members of the Women Strike for Peace Movement did indeed publish Peace de Resistance, a cookbook that included simple recipes for those days when WSP’s efforts were needed to protest against the testing of nuclear weapons.

As Invisible Colors makes clear, representing the nuclear is not an easy task. First, the subject itself is delicate. It evades our standard notions of materiality and our very limited and very human conception of time. It makes it ethically difficult to represent terrible loss and suffering, to draw any aesthetic pleasure from it.

Michael Light, 045 STOKES 19 kilotons Nevada 1957. From 100 Suns : 1945-1962

The most powerful obstacle to a straightforward and honest nuclear representation, however, is the industry’s dark power. Countries like the USA and France, for example, never shied away from censorship and cover-ups to ensure that nuclear activities remained shrouded in secrecy. In France, the media were pressured so that the public didn’t have to face any unpleasant questioning of what was happening in mines in Madagascar, in Gabon and in France. The U.S. documented their activities in a way that would render the atomic age fabulously visual. The military-produced images of the US tests in the Pacific are so spectacularly appealing that they eclipse the human and animal victims and any longlasting damage to the landscape.

The author also reveals how the nuclear industry uses art to support their agenda, reaching out to artists and sponsoring comic books and exhibitions. Just like car manufacturers and (fossil fuel) energy giants are doing today to greenwash their industry.

As Invisible Colors brilliantly argues, art and humanities must keep the nuclear memory radioactive and alive. Because recording and remembering are also political acts.

Carole Langer, Radium City, 1987

Igor Kostin, Robots couldn’t handle the intense radiation at Chernobyl so the nuclear cleanup job fell to the “liquidators” — a corps of soldiers, firefighters, miners, and volunteers. Part of the series Chernobyl – The Aftermath, 1986. Photo

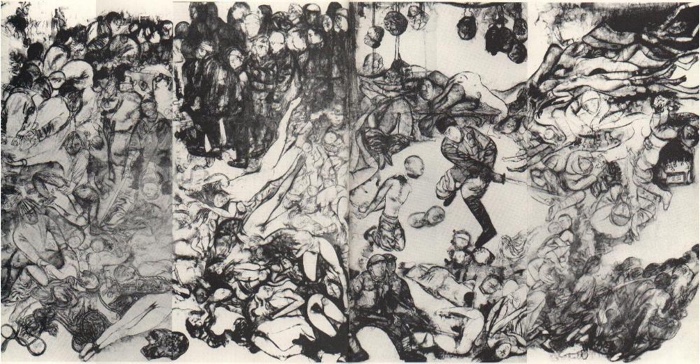

Maruki Iri and Maruki Toshi, Nanking Massacre, 1975. Part of the Hiroshima Panels

Keiji Nakazawa, Barefoot Gen, 1973-1985

Yosuke Yamahata, A woman and her child appear in a state of shock the day after the atomic bombing of Nagasaki, 1945

Shomei Tomatsu, Beer Bottle After the Atomic Bomb Explosion, 1961

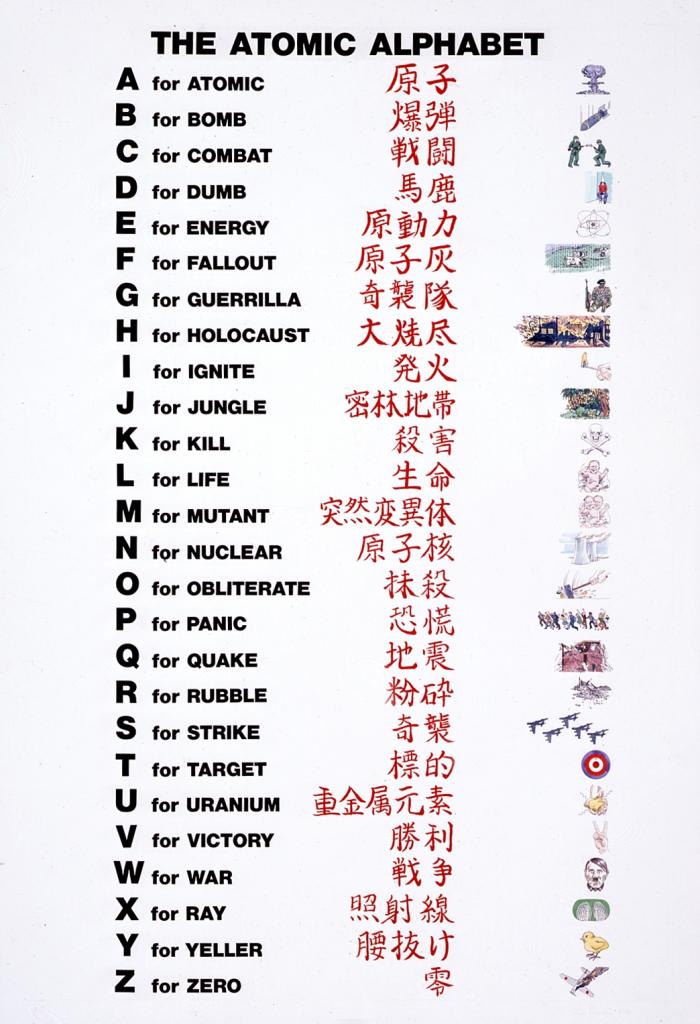

Chris Burden, The Atomic Alphabet, 1980

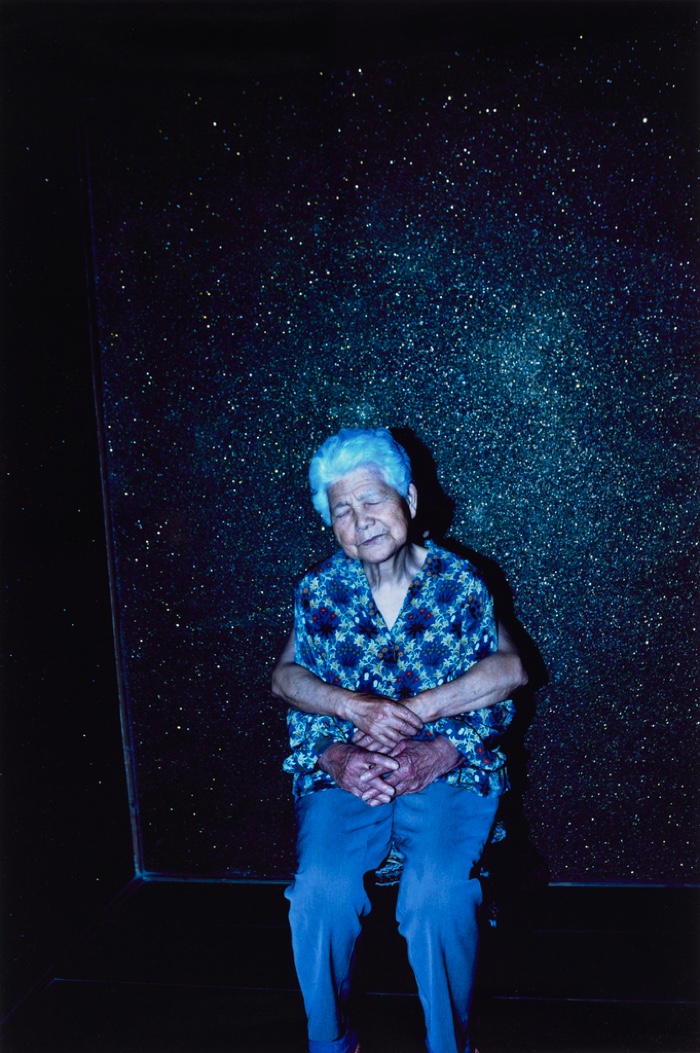

Shiga Lieko, Mother’s Gentle Hands, 2009

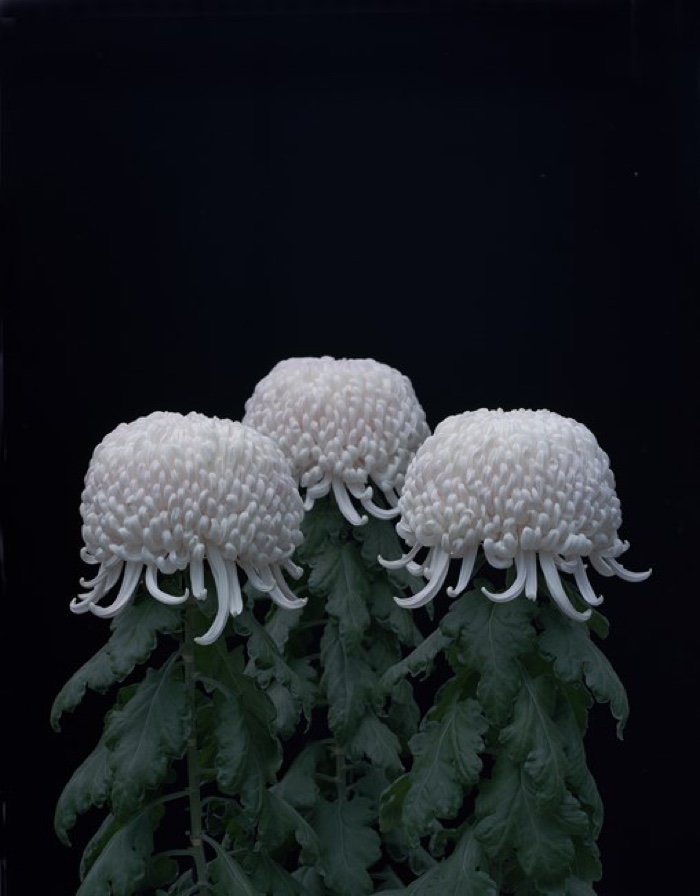

Tomoko Yoneda, Chrysanthemums from the series Cumulus, 2011

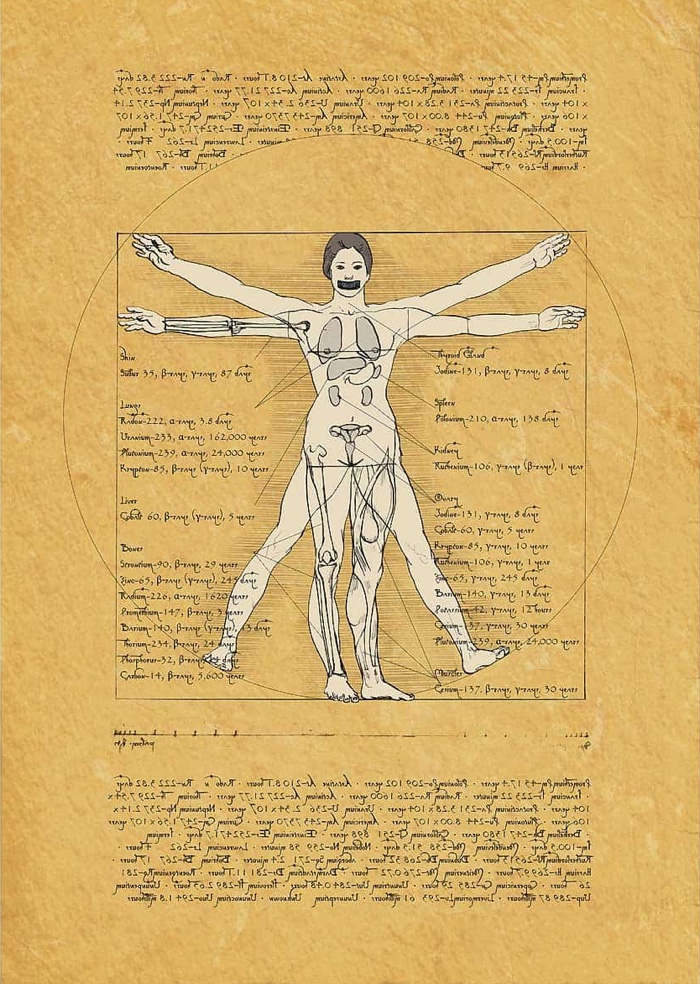

Ikeda Ai, Sievertian Human – Wisdom, Impression, Sentiment, 2015

Jürgen Nefzger, Sellafield, England, 2005. From the series Fluffy Clouds

Jürgen Nefzger, Kalkar, Deutschland, 2005. From the series Fluffy Clouds

Critical Art Ensemble, Radiation Burn, 2010

Rebecca Zlotowski, Grand Central, 2013 (trailer)

Robert Del Tredici, The Richest Uranium Mine on Earth, 1986

Related book: The Nuclear Culture Source Book.

And stories: Perpetual Uncertainty. Inhabiting the atomic age, Sonic Radiations. A nuclear-themed playlist, After The Flash. Photography from the Atomic Archive, Gamma Sense. Open, fast and free gamma radiation monitoring for citizens, Anecdotal radiations, the stories surrounding nuclear armament and testing programs, Inheritance, a precious heirloom made of gold and radioactive stones, etc.