Susan Schuppli, Trace Evidence (video still), 2016. ©-Polly-Yassin

Nuclear cultures, its promises, dangers and dilemmas, are never far away from media headlines. Sometimes the stories are terrifying (as in Kim and the Donald fighting over the title of “World’s Most Irresponsible Leader”.) Other times, the stories echo events or political choices from the past: radioactive waste that keeps on piling up, toxic legacies of European bomb tests in its African colonies, seaborne radiation from Fukushima nuclear disaster detected on the U.S. West Coast, etc.

Perpetual Uncertainty, an exhibition that opened a few weeks ago at Z33 House for Contemporary Art in Hasselt, reminds us that the nuclear forms the backdrop of our lives, for thousands of generations to come. And even beyond.

The show brings together artists from across Europe, the USA and Japan to investigate experiences of nuclear technology, radiation and the complex relationship between knowledge and deep time.

Perpetual Uncertainty is amazingly informative and stimulating. It helps the public face its anxieties by visualizing every material and immaterial aspect of nuclear technology: the extraction of uranium from the ground, the production of energy, the repercussions of deliberate and accidental explosions and the thorny subject of radioactive waste. Through each of work in the show and each aspect they explore we get to realize how much man-made radiation has transformed our understanding of materiality, knowledge and time.

While the exhibition helps us comprehend what it means to inhabit the atomic, it also leaves space for the impasses and dilemmas that characterizes nuclear culture, a subject which, as we know, still brings far more questions than answers.

Nick Crowe and Ian Rawlinson, Courageous, 2016

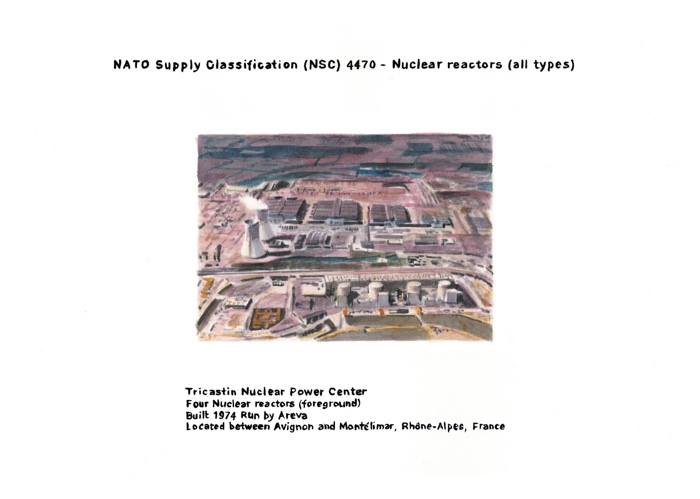

Suzanne Treister, NATO, 2004-2008. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Z33 is an ideal venue for a reflection on nuclear culture. First, because Z33 is a research-based institution that explores the critical perspectives that art, design and architecture can add to the understanding of the contemporary challenges and dilemma that society is facing today.

Furthermore, Z33 is located in Hasselt, Belgium. Now you might not automatically associate Belgium with nuclear blasts. Yet, the country is disturbingly linked to the bombs that were dropped on Japan by the U.S.A. back in 1945. At the time, Belgium had made itself incredibly rich by extracting the mineral resources of its colony, the Belgian Congo. One of the mines was located in Shinkolobwe and had been identified as a source of uranium. The quality of the mineral was so high that it was sold to the U.S. and supplied nearly a large part of the uranium used in the bomb dropped over Hiroshima, and much of the related product of plutonium that went into the one that destroyed Nagasaki.

Here’s a few lines about some of the works in the show:

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Kuannersuit, Kvanefjeld, 2016

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Kuannersuit, Kvanefjeld, 2016

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Kuannersuit, Kvanefjeld, 2016. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway, Kuannersuit, Uranium ore from the experimental mine at Kvanefjeld, 2016. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

The region of Kvanefjeld in southern Greenland is the site of rich rare earth mineral resources and large deposits of uranium. It is also a place of incredible beauty with unspoiled mountains, wooden houses and deep blue fjords.

Foreign mining companies have shown great interest in Kvanefjeld and a recent relaxation of regulations by the government of Greenland has opened up the possibility of creating an open pit mine there.

Lise Autogena and Joshua Portway spent the summer 2016 traveling in South Greenland, meeting residents, politicians, farmers and government officials and uncovering the deep divisions surrounding the mining project.

For some, the mining activity is a means of gaining autonomy from Denmark and keeping younger generations employed.

However, opponents to the project believe that courting foreign investors amounts to swapping one form of dependency for another, with the added risk of environmental degradation, health hazard for the community and their livestock as well as a threat to traditional ways of living from the land and the sea.

According to environmentalist NGOs, the mining project does not ensure that environmental risks are reduced as much as is practically possible. For example, polluting tailings from the refinery are disposed of in Lake Taseq high up in the Narsaq valley river system. From here, there is a high risk that radioactive isotopes and toxic chemicals will enter the groundwater, rivers, fiords and the sea.

The divisions within the local communities illuminate the dilemmas of our times and underline that the quest for energy and ‘progress’ has trade-offs and costs for society and the whole ecosystem.

Yelena Popova, Unnamed (Video still), 2011

Yelena Popova’s Unnamed video essay combines personal and archival footage to relate the story of her hometown in Russia.

Ozyorsk (codenamed City 40) was a “secret” town, built to accommodate the scientists and technicians of a plutonium factory along with their family. The residents were forbidden from leaving the city or making any contact with the outside world. For decades, this city of 100,000 people did not appear on any maps.

The government went to great lengths to ensure that the city’s occupants would be content with their secluded lives: they enjoyed high quality healthcare and education, generous wages, beautiful buildings and parks as well as well-stoked grocery stores.

The film goes on to reveal how, in 1957, the plant was the site of the Kyshtym nuclear disaster, the third-most serious nuclear accident ever recorded. The Soviet managed to keep the explosion secret for years. It’s only in 1976 that scientist Zhores Medvedev made the nature and extent of the disaster known to the world.

As the film develops, the representation of the disaster becomes a metaphor for the failure of science in the twentieth century and the difficulty to both understand a phenomenon (thus comprehending its details) and knowing it (by being aware of its consequences and significance).

Today, the city of Ozyorsk is still home to most of Russia’s nuclear reserves and people living in the area remain exposed to high levels of radiation.

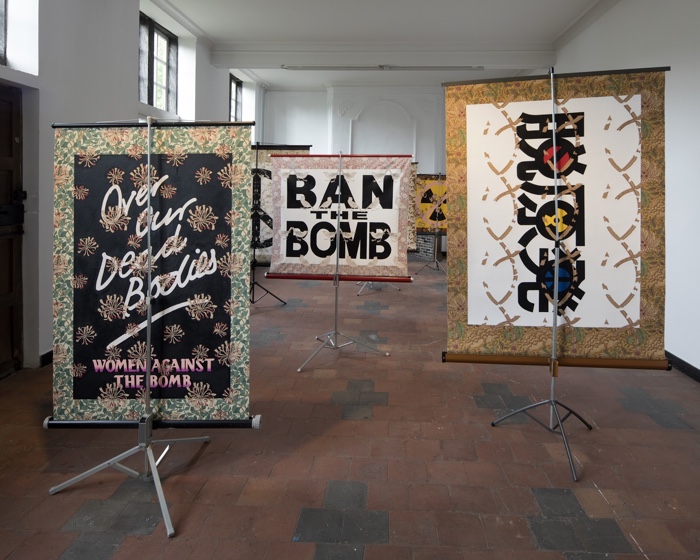

David Mabb, A Provisional Memorial to Nuclear Disarmament. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

David Mabb, A Provisional Memorial to Nuclear Disarmament. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

A Provisional Memorial to Nuclear Disarmament combines William Morris fabrics with anti-nuclear symbols and slogans. The association is less arbitrary than it might seem. The British Ministry of Defence used the Morris Tudor Rose print (1883) for over thirty years (from the 1960s through to the 1990s) to furnish the officers’ quarters inside its nuclear submarines.

In 2014, David Mabb visited one of those submarines, the decommissioned HMS Courageous which the public can now visit naval dockyard in Plymouth, on the southwest coast of England.

Famous 19th century socialist Morris would have probably been upset to see his designs used inside instruments of war and violence. Mabb reappropriates Morris’ fabrics and pairs them with anti-nuclear protest signs and slogans from different times and countries.

The works are presented on old-school freestanding projection screens. Distributed over two exhibition rooms, they look like an actual protest march.

As Mabb explained the title of the work in The Bulletin:

The work is called A Provisional Memorial to Nuclear Disarmament.” “Provisional” because Britain’s Conservative government has—despite considerable opposition—decided to go ahead with the commissioning of a new generation of Trident nuclear submarines armed with nuclear missiles. And just last week, it confirmed that it is going to proceed with Hinkley Point, the first nuclear power station to be built in Britain for two decades.

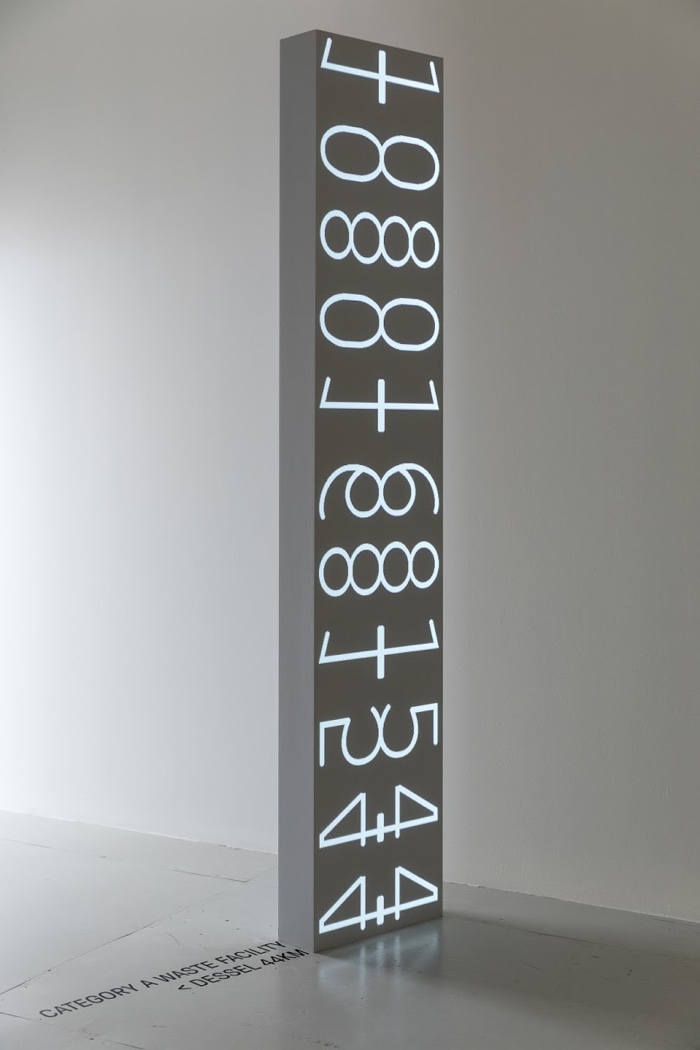

Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead, Temporary Index (Dessel), 2017. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Will people in a distant future be aware of radioactive sites? Will they understand the language we try to develop now to warn them of the danger? Thomson and Craighead’s Temporary Index is a totem that marks both time and space.

First, the totem acts as a signpost, mapping the distance between Z33 and the Category A Radioactive Waste Facility to be built at Dessel, 44km from the gallery.

Temporary Index also counts down the seconds that remain before the nuclear waste facility is finally deemed safe for humans. The numbers displayed on the screen are overwhelming. Yet, the radioactive substances they point to have a super short life compared to others. They are low-level radioactive waste that will require ‘only’ 300 years until they no longer represent a threat. Other waste disposal facilities have to provide protection for over hundreds of thousands of years, which far outstrips the understanding that most of us have of time.

Temporary Index, Chernobyl Reactor #4, Ukraine, an earlier version of the Temporary Index, was exhibited at the Perpetual Uncertainty show in Umea last year. It marked the distance from the museum to the Chernobyl reactor and visualized the 20,000 years of radioactive decay necessary for the Ukrainian location to be safe, providing us with a glimpse into the vast time scales that define the universe in which we live, but which also represent a future limit of humanity’s temporal sphere of influence.

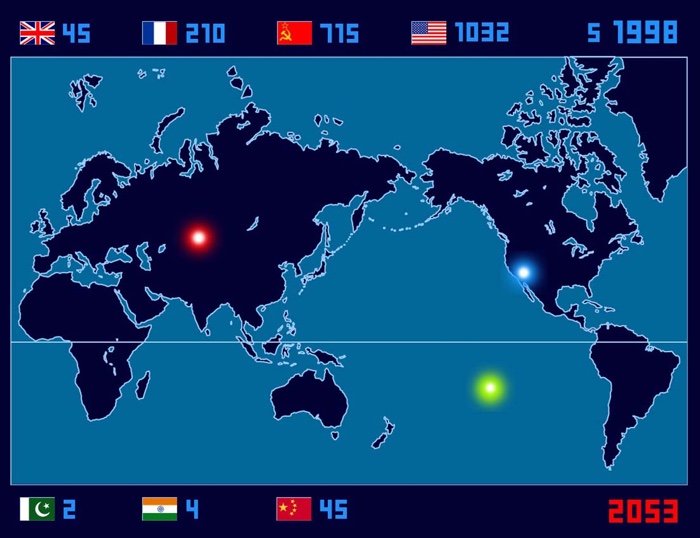

Isao Hashimoto, 1945-1998 (video still), 2003

Isao Hashimoto, 1945-1998 (video still), 2003

Isao Hashimoto’s video doesn’t need much explanation. His video plots on a map every single known nuclear test and explosion that took place across the world from 1945 until 1998. 2053 in total. It’s shocking to discover how gaily the UK and France have tested their nuclear weapons in distant territories.

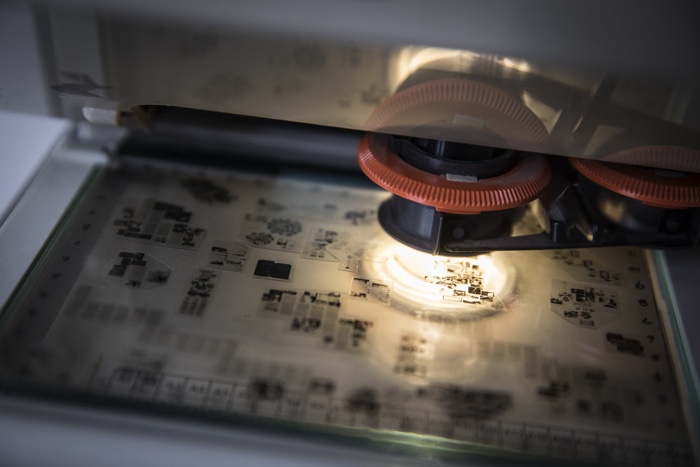

Shimpei Takeda, Trace. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Shimpei Takeda used photo-sensitive material to physically expose the traces of radiation present in the samples of the contaminated soils he collected throughout the landscape surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant.

He used no camera for the photographic process. He simply placed the radioactive soils on photo-sensitive films in a light-tight container and left them there for a month. Radioactive substances emit radioactivity to expose gelatin halide on the surface of photographic film.

The number and size of the white dots are proportional to the amount of radiation present in the soil.

Shuji Akagi, Decontamination of My Yard, Fukushima City, 2013

Shuji Akagi, Fukushima City, 2011-2017. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Since the nuclear disaster in Fukushima in 2011, Shuji Akagi has been documenting the changes his hometown is going through. Most of his images feature big plastic blue or green bags and tarps. They seem to be everywhere: in the streets, in the fields, in people’s backyard, etc. They are filled with contaminated soil. In his photos you also see how people have resumed their daily life. Only now they have to navigate around the plastic-wrapped manifestation of invisible radiation.

It has been estimated that the decontamination process could take more than 100 years.

More works and images from the exhibition:

Dave Griffiths, Deep Field (UnclearZine), 2016. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Dave Griffiths, Deep Field (UnclearZine), 2016. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

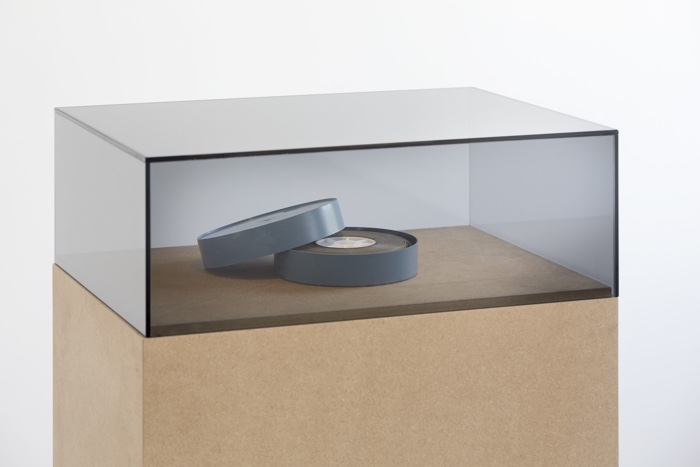

Eva and Franco Mattes, The Last Film, 2016. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Ken & Julie Yonetani, Crystal Palace: The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nuclear Nations, 2013. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Robert Williams and Bryan McGovern Wilson, Cumbrian Alchemy, 2013. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Exhibition view of Perpetual Uncertainty at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Cécile Massart, Laboratoires, 2013. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Cécile Massart, Colours of Danger for Belgian High-Level Radioactive Waste, 2017. Exhibition view at Z33. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

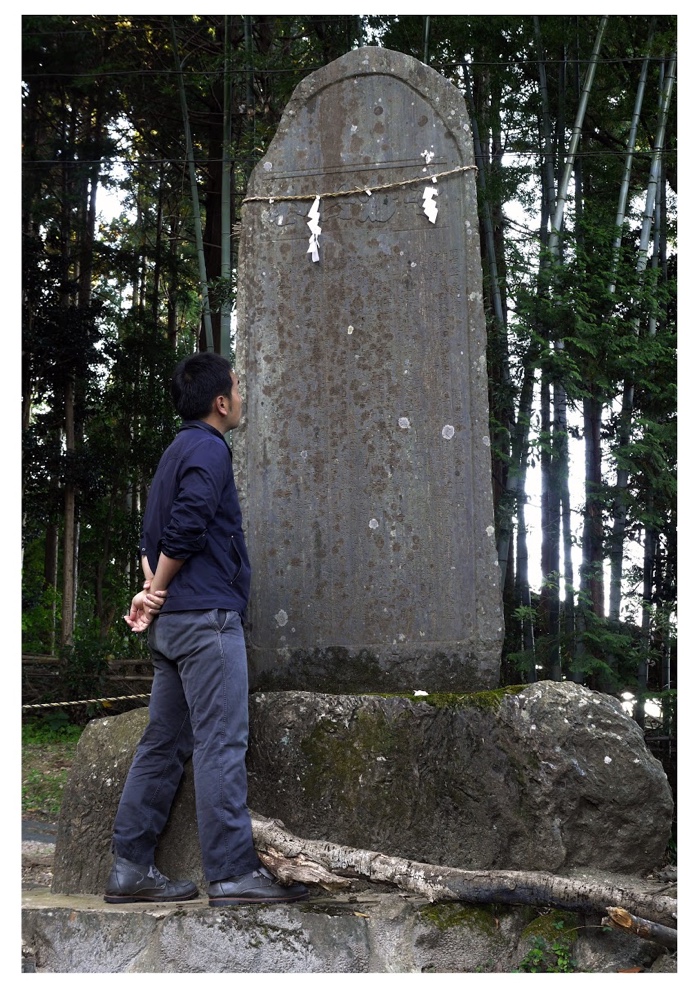

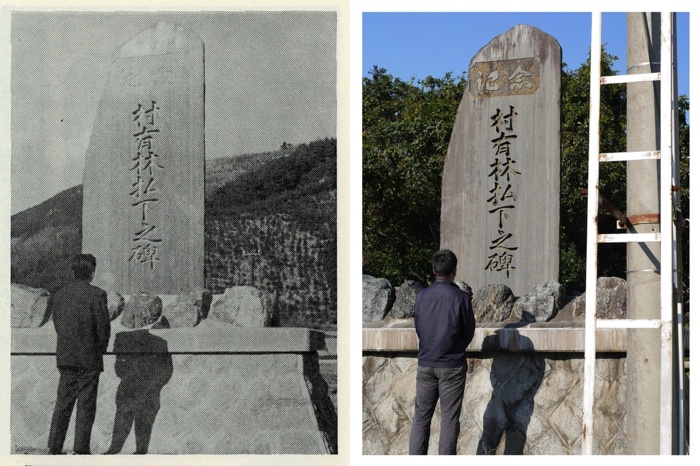

Kota Takeuchi, Take Stone Monuments Twice, 2013-2016

Kota Takeuchi, Take Stone Monuments Twice, 2013-2016. Photo via z33 research

Kota Takeuchi, Take Stone Monuments Twice, 2013-2016. Photo via artsy

Nuclear Culture presents: Perpetual Uncertainty is at Z33 in Hasselt until 10 December 2017. Entrance is free.

More photos from the exhibition on Z33 flickr set and on mine.

Perpetual Uncertainty is produced by Bildmuseet, Umeå and curated by Ele Carpenter with the support of Z33 and Arts Catalyst London.

Related stories: Sonic Radiations. A nuclear-themed playlist commissioned by Z33 for the exhibition and The Nuclear Culture Source Book.