Field to Palette: Dialogues on Soil and Art in the Anthropocene, by Alexandra Toland, Jay Stratton Noller and Gerd Wessolek.

Publisher CRC Press describes the book: Field to Palette: Dialogues on Soil and Art in the Anthropocene is an investigation of the cultural meanings, representations, and values of soil in a time of planetary change. The book offers critical reflections on some of the most challenging environmental problems of our time, including land take, groundwater pollution, desertification, and biodiversity loss. At the same time, the book celebrates diverse forms of resilience in the face of such challenges, beginning with its title as a way of honoring locally controlled food production methods championed by “field to plate” movements worldwide. By focusing on concepts of soil functionality, the book weaves together different disciplinary perspectives in a collection of dialogue texts between artists and scientists, interviews by the editors and invited curators, essays and poems by earth scientists and humanities scholars, soil recipes, maps, and DIY experiments.

Center for Land Use Interpretation, Ambrosia Lake Disposal Cell, from Perpetual Architecture: Uranium Disposal Cells of America, 2012

Debra Solomon and Jaromil, Entropical, 2015

Very few of us realize the importance of soil and the deep connection we share with it. Our food system rely on the health of soils. Our dwellings, our modern infrastructures of communication and transports depend on the support of soils. Soil again is the place we open up when we need to extract minerals and other sources of energy and construction material. We need soil to absorb carbon, filter water and ensure the wellbeing of our ecosystems. It’s there, underneath our feet. Yet, we barely acknowledge its existence.

Over time and with the help of globalization, concrete and modern life, we’ve become so alienated from soil that we’ve allowed it to deteriorate. Soil degradation is so severe that, some scientists predict, topsoil will have disappeared by 2070. All of it.

The ambition of the editors and contributors of the book Field to Palette: Dialogues on Soil and Art in the Anthropocene is to help society reconnect with soil. The chapters are either essays that explore some of the cultural articulations of soil or incredibly informative conversations between artists, activists and scientists who share their thoughts about the material properties, cultural histories, environmental functions and existential threats of soil.

Field to Palette is an amazing publication. Its almost 700 pages are packed with photos, surprising information and moving encounters. I wish i had the time to talk about everything i’ve learnt in the book. The unexpectedly sophisticated sensory abilities of nematodes or the method to turn plastic-free baby diapers into planters and nutrients for trees, for example. Since one of the greatest achievements of the book is the way it demonstrates the important role that artists can play in raising discussions with the public and in participating to the solution to the many challenges soil faces today, i’ll dedicate the rest of my review of the book to just a few of the artworks and stories i discovered in Field to Palette.

Franziska & Lois Weinberger, Laubreise at the Austrian Pavilion in Venice, 2009

Agnes Denes, Wheatfield – A Confrontation, 1982

The book is articulated around six functions, six entry points to help us appreciate soil. The first Function of soil is Sustenance. Soil provides us with food, biomass and all forms of nourishment. The intro to the section informs us that 99% of human nourishment comes from 3% of available land. And that, sadly, about a third of that available land is compromised because of chemical pollution, erosion, salinization, etc.

The section starts with the best advocate soil could dream of: Agnes Denes, the artist behind the iconic and spectacularly thought-provoking Wheatfield – A Confrontation. The artist dialogues with the president of the International Union of Soil Sciences, Rattan Lal, about the close connections that could be weaved between conventional agriculture and urban agriculture.

Tattfoo Tan, S.O.S. Mobile Classroom at Farm City Fair, Brooklyn, New York, 2010

Philosopher and curator Sue Spaid writes about 4 artists-farmers whose “artisan soil” practices establish clear links between the health of our soil and the health of our food and of the environment. Their resolution to show their soil as art is an open invitation to cultural institutions to value soil on par with more ‘traditional’ types of museum treasures.

I was particularly moved by artist Maria Michails‘s comment on “energy landscapes” which she sees as a growing tendency to turn good farming lands usually dedicated to growing crops into surfaces that will produce energy through the plantation of plants for biofuel or the installation of solar panel or wind turbine farms.

Parto Teherani-Krônner and Rozanne Swentzell call for more attention to feminist and indigenous perspectives in soil protection debates. They believe that we should rehabilitate the term ‘meal’ because it has a more holistic dimension than ‘food’. A true meal culture has the potential to counter the effects of globalization and regain respect for food traditions, soil and the animals we eat.

The second function of soil is to be a Repository, a source of energy, raw materials, pigments but also poetry.

In that section, Peter Ward offers a guide for collecting and working with earth pigments. I also enjoyed artist Dave Griffiths, science communication lecturer Sam Illingworth and illustrator Matt Girling‘s look at the technocultural archiving of nuclear waste and at the necessity to communicate to far future beings about ancient hazards buried deep below their feet.

Margaret Boozer, Correlation Drawing/ Drawing Correlations, 2012

Margaret Boozer‘s installation Correlation Drawing/ Drawing Correlations features soil samples from all 5 boroughs in New York, extracted over the span of 15 years by Dr. Richard K. Shaw and his team for the New York City Reconnaissance Soil Survey. The work is particularly relevant in urban contexts where most inhabitants might not give any consideration to the soil underneath the concrete.

Soil health and plant nutrition researcher Taru Sandén and artist Terike Haapoja talk about the difference between organic and inorganic carbon and made me want to have a go at the Tea Bag Index, a citizen science method to gather data on decomposition and carbon stabilization.

Function 3 explores soil as an Interface, a site of environmental interaction, filtration and transformation. It’s a dark chapter with toxic infiltration, river bank erosion, climate change-related flooding, industrial runoff, etc. It is also one in which you take the measure of the superhero power of plants that are capable of drawing out toxins from soil, protecting it from the erosive impact of rain and wind and preventing slopes from slipping into waterways.

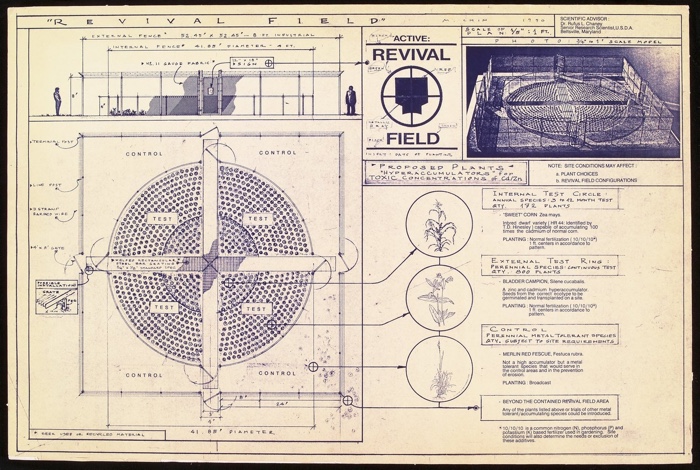

Mel Chin, blueprint for Revival Field, 1990

Mel Chin, a pioneer in phytoremediation, demonstrated plant potency in several of his works. Talking with curators Patricia Watts and Amy Lipton (the co-founders of ecoartspace), he recounted the story of Revival Field. In the early 1990s, the artist collaborated with research agronomist Rufus Chaney to prove that hyperaccumulator plants can cleanse soil of toxic metals like cadmium and zinc. The work, which confirmed what had so far only been a scientific hypothesis, continues at a contaminated Superfund site, Pig’s Eye Landfill in St. Paul, Minn.

In a discussion between artist Aviva Rahmani and professor of soil science Ray Weil about their respective approaches to restoration work to degraded systems, Weil explained how he used mega daikon radishes to help wean agribusiness farmers from the use of heavy fertilizers.

Sally Mann, Untitled (Body Farm #18), 2000

Environmental scientist Farrah Fatemi and curator Laura Fatemi selected four artists from the exhibition Rooted in Soil to illustrate how old energy can be harnessed into new growth. One of these artists is Sally Mann whose disturbing photos of decomposing corpses in a body farm remind us of our visceral connection to earth.

Function 4 looks at the soil as Home, a biological hotspot, a gene pool, a habitat for bacteria, fungi and all sorts of organisms. That’s where i learnt that more than a quarter of the planet’s known species live in the soil. The life underneath our feet might be invisible but it is dynamic and responsible for almost all lives above the ground.

The chapter shows how fiels as diverse as biohacking, Afrofuturism and postcapitalistic sculptures can reveal the activity and even ‘hidden narratives’ of soil. I have a text in that section. Although ‘text’ is a big word since it’s Amy Franceschini who does all the hard work in the interview i had with her about seeds and genetic biodiversity.

Suzanne Anker, Astroculture (Eternal Return), 2015

Interviewed by Regine Rapp and Christian de Lutz, the cofounders of Art Laboratory Berlin, Suzanne Anker made some fascinating comments on the toxicity in the soil since Industrial Revolution and on extraterrestrial farming.

Wanuri Kahiu, Pumzi Trailer, 2010

Professor of geology and environmental engineering, Peter K. Haff and filmmaker Wanuri Kahiu have an engaging exchange about the importance of using speculative narratives when technology is accelerating but human processes are not.

Function number 5, Heritage, sees soil as an embodiment of cultural memory, identity and spirit. Soil adopts the crucial but difficult to assess function of providing us with aesthetic pleasure, recreational enjoyment, cognitive development and spiritual enlightenment.

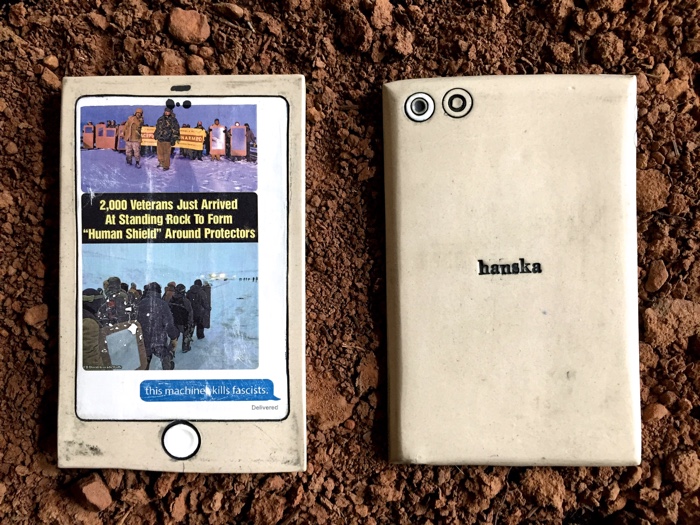

Cannupa Hanska Luger, The Weapon is Sharing (This Machine Kills Fascists), 2017

Artist Cannupa Hanska Luger calls for a re-indigenization of Western thought and argues that the best way to protect the soil and in particular its cultural heritage is to share it.

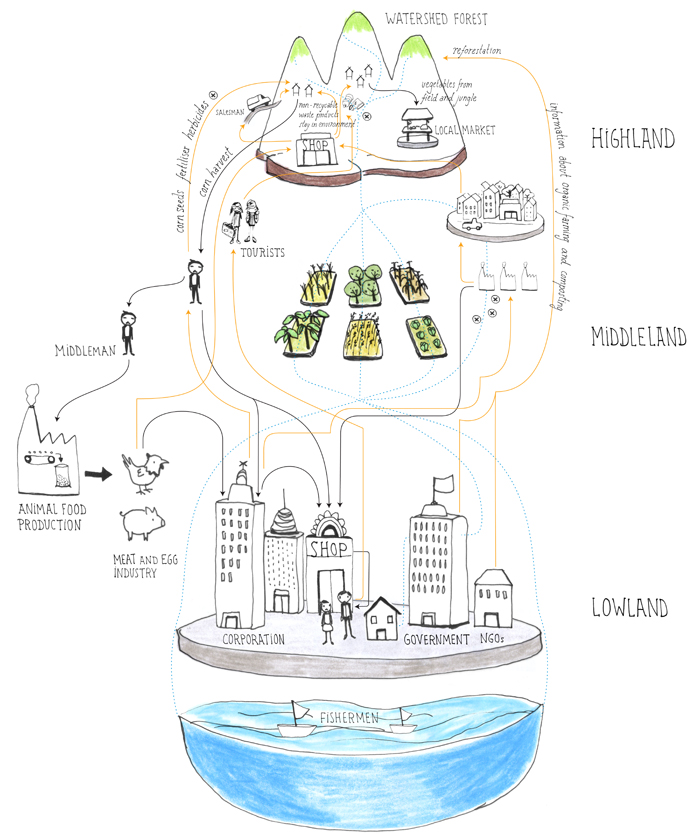

Ruttikorn Vuttikorn and Myriel Milicevic, Stories from the Hills: Tales of the Lowland

Play activist Ruttikorn Vuttikorn, artist and interaction designer Myriel Milicevic and specialist of indigenous studies in Thailand Prasert Trakansuphakon give an enlightening perspective on how indigenous people’s life on the high hills of Northern Thailand can inform the urban ways of communal living of the “Lowlanders”. The best quote in their contribution to the book is by a village leader who turned down an offer from the U.S. to export 25.000 jars per year of their local honey. “Nature is not a manufacturer,” he explained.

Function 6 explores soil as a Stabilizer, a platform that enables the construction of structures, infrastructures and socioeconomic systems. Our buildings, underground and overground transport systems, sewers, communication networks and other modern infrastructures would not exist without the space and stability that soil offers for their construction.

Center for Land Use Interpretation, Uranium disposal cells in Mexican Hat, Utah, from Perpetual Architecture: Uranium Disposal Cells of America, 2012

The research and education organization Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI) talk about Perpetual Architecture: Uranium Disposal Cells of America, a 2012 exhibition that explored the extent of uranium disposal cells in the US and the kind of unintended “land art” objects the infrastructures left in the landscape.

Lara Almarcegui, The Rubble Mountain, Sint-Truiden, 2005

Lara Almarcegui works with anthropogenic soil substrates, rubble, stones, sand, landfill soil and other waste construction materials to make us think of the true -underground- origin of a building.

Ellie Irons in collaboration with professor of environmental biology Jean Louis Morel speculate on a Soil Assembly and Dissemination Authority (SADA), an hypothetical and future city agency responsible for research, production, distribution and outreach related to an essential (and no longer naturally available) resource: soil.

Related stories: Ecovention Europe: Art to Transform Ecologies, 1957-2017 (part 1) and (part 2), The scars left by electronic culture on indigenous lands, Eulogy for the weeds. An interview with Ellie Irons, Interview with Cecilia Jonsson, the artist who extracts iron from invasive weeds, Dust Blooms. Can we put a price on the services that urban flowers provide?, Experiments in sound, soil and microbial fuel cells, No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Grounds, Perpetual Uncertainty. Inhabiting the atomic age, HYBRID MATTERs: The urks lurking beneath our feet, The Seed Journey to preserve plant genetic diversity. An interview with Amy Franceschini, etc. I didn’t realize i had written so many articles related to soil.