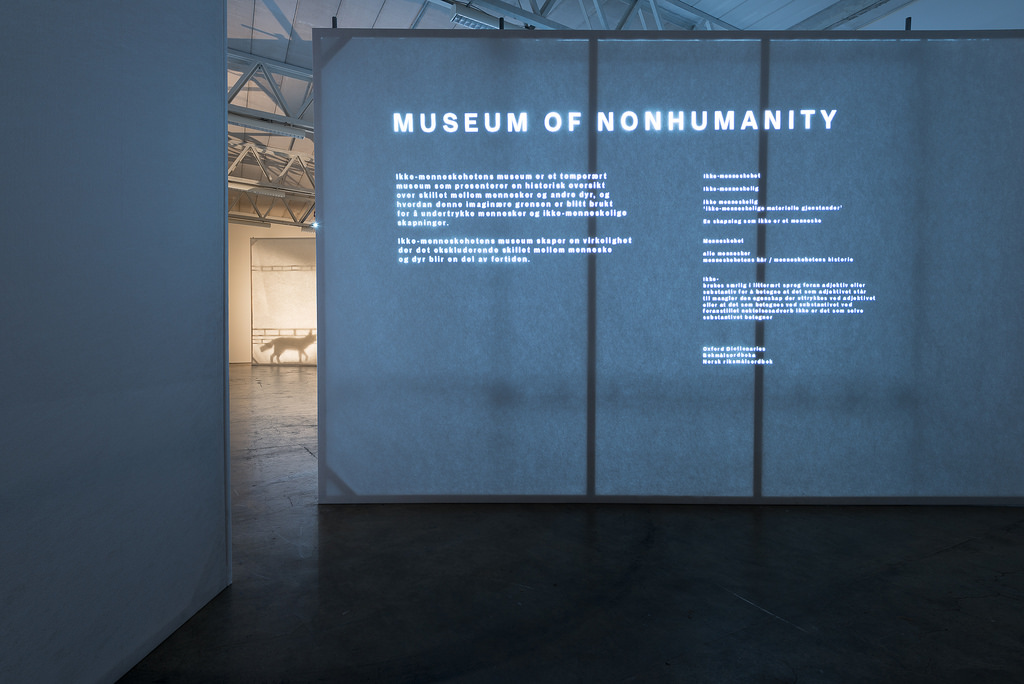

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Many of us, consciously or not, believe in human exceptionalism. We assume that the human species is not only ‘categorically or essentially different than all other animals’ but that it is also the most significant entity of the universe. Furthermore, at several moments throughout history, a group of people have declared another group of people to be nonhuman or subhuman and have used the argument to justify slavery, oppression and genocide. Examples abound. Think of how the Nazis defined Jews, Roma, Slavs and other non-Aryan “inferior people” as Untermensch. Or how Belgium brought 60 Congolese people to live in a human zoo for visitors of the 1897 International Exposition (and the 1958 one) to gape at.

Such atrocious practices are not confined to the past, alas! Women and girls from Iraq’s Yazidi minority are routinely enslaved, raped and tortured by IS militants who regard them as sub-human. Palestinians are discriminated against on a daily basis and called snakes or animals by prominent figures in Israel. Even today‘s hate speech contain elements of dehumanization.

The Museum of NonHumanity is an itinerant museum that presents the history of the distinction between humans and other animals, and the way that this imaginary boundary has been used to oppress human and nonhuman beings.

The Museum of Nonhumanity was launched by History of Others, a large scale art and research project led by visual artist Terike Haapoja and writer Laura Gustafsson. The duo collaborate with experts in ethology, cognitive sciences, civil-rights and animal-rights activism and other culture practitioners to look at the issues that arise from our anthropocentric world view. In an effort to open new paths for more inclusive notions of society, The Museum of Nonhumanity also teams up with local individuals and organizations to set up a program of lectures, guided tours and seminars that explore local environmental and social issues.

I discovered The Museum of Nonhumanity a couple of weeks ago while i was in Moss, Norway, for the press view of MOMENTUM 9, the brilliant Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art. The Museum of Nonhumanity was one of the two artworks that moved me the most at MOMENTUM because it uses a compassionate, perceptive and pertinent lens to explore some of the issues that mar our relationship with the other inhabitants of this planet.

I asked Terike Haapoja and Laura Gustafsson to tell us more about their art & research project:

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Hi Terike and Laura! Why do you think it is important to draw attention to the topic of dehumanization nowadays?

When you look at any major crises of our world today, be it related to environmental or animal rights, war or terrorism, you can as a rule find an element of human-animal distinction at play. You can find it in explicit instances, such as the dehumanising language used by right wing xenophobes in Europe of immigrants, but also in the internalised dehumanisation imbedded in structural racism and sexism. And there’s also the fact that nature and all the other species have, because they’re literally “non-human”, no way to be visible to the justice system as a victim of a crime. Underneath all this is a logic where defining something or someone as less human justifies discrimination and abuse.

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

There seems to be an enormous amount of research and thoughtful selection behind the work. How did you select which particular historical case illustrated a specific chapter? Why did you chose Rwanda to typify Disgust for example? etc.

We weren’t interested in cataloguing all the atrocities in history that had been justified by dehumanisation, but in examining the rhetoric devices and the reasoning and motives that connect these actions. So while doing research on concrete cases, we started to think of key words that open up a specific viewpoint to the phenomenon of this boundary making: using someone or -thing as resource, referring them to something disgusting, creating physical or emotional distance between “them” and “us” and so on. Rwanda, the Holocaust or the horrible history of colonised Congo are well documented, but once you start to look into how and where the human – animal boundary is constructed, you see that the boundary making is present in seemingly innocent details, like the guidelines of scientific research, in how we talk about the body and female body in particular, or in the key ideas of western philosophy. its not something that happens somewhere there, or to someone else. We wanted to bring in this complexity.

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

I was particularly moved by the story of the female members of the Red Guards that were imprisoned after the Finnish Civil War. Is their history well known in Finland? The reason why i’m asking that is that i’m Belgian and when i was at school, we were never told about the atrocities committed by Belgium in Congo. I learnt about it much later, while studying in another country. This has changed of course (to a certain extent) and i think children learn about it at school now, but the awakening is actually quite recent. Also i was discussing with a Swedish artist recently and she told me that most Swedish people actually do not know much about the discrimination the Sami people face in Sweden and possibly in other countries too. Do you feel that most nations tend to try and cover up all the terrible and cruel acts they committed in the past?

And do you think it would still be possible to bury atrocities nowadays, in this age of surveillance and over sharing?

The history of the civil war is still very much silenced in Finland, just as is the atrocities towards Sámi people and their culture. There is a lot of work to be done. It seems that the mechanism of dehumanisation is at play in nation making itself, where unwanted and negative characteristics are projected on anyone that is desired to be kept out of the nation. Perhaps that’s the reason why it’s always easier for a nation to see and acknowledge other histories than its own.

In terms of whether it’s possible to bury atrocities – what’s central is that once this boundary has been established, it’s possible to perform these atrocities in plain sight. They become invisible to the collective moral code that forbids them, and in ways that are immune to surveillance. And that happens all the time. Once someone or -thing is collectively defined as “animal”, anything can be done to it.

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

What i find remarkable about the work is that the historical documents you selected sometimes echo so well current situations and opinions. In fact, while reading some of the quotes, i assumed that they were all from decades ago but the dates underneath each quote revealed that some of the most appalling ones were actually found in forum discussions or politician declarations of recent years. Do you see hope in the way we treat each other?

There is something very effectively violent in the culture that we live in, and something that enables ‘othering’ and looking at violence from a distance. The technologies we live with are definitely a product of that culture, and we are a product of it. You can go to the most liberal leftist bubble and see how, even there, people use dehumanising and violent language online. So it’s something that is in us, not out there, and the only hope there is is that we are committed to being self reflective and cultivating solidarity and empathy, and acting against these mechanisms.

The information you share is laid out in a rather neutral way. The way you selected each theme and document is not neutral of course but you leave every document speak for itself. What do you hope people will get from visiting the exhibition or reading the catalogue? Is it about informing them? About inviting them to pause and take a critical look at their own prejudices? Or did you have other objectives in mind?

We decided very early on that we would only include archival material, and reference everything very well. In that way it is not only information, it’s also evidence. This way it becomes a memorial museum, where these things have been put on show, to remind us of a past we don’t want to return. What we’d like the viewer to take with them is an understanding of how fast things can move from words to action.

We’d also hope that it would be a way for people to see that human rights violations and environmental or animal rights issues are not competing struggles, but born out of the same roots. Environmental destruction and factory farming is killing our planet, and it’s happening in plain sight just because this boundary has been so well established.

It’s good to remind here that an important part of the project is programming, which is built by local practitioners and for local audiences. The programming is all about proposing bridges to a more sustainable coexistence. We had lot of programming, a vegan cafe and a book shop in Helsinki, and we will be having that in our Italy exhibit too. In Momentum we will be working with local guest guides and environmental protection activists, and organise a seminar later in the fall. So the project is not only looking back, but it really is a platform for looking forward too.

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

Museum of Nonhumanity, installation at MOMENTUM9, 2017. Photo by Istvan Virag

The installation i saw at Momentum9 is quite stunning, it’s hard not to be drawn into it. How do you turn a research process or catalogue into an installation like this? Which kind of artistic decisions did you take in order to translate a catalogue into a piece of visual art?

We knew it would be encyclopaedic from the beginning, and that it would be a memorial museum. You just have to work with the material and start to organise it and trust that pieces will fall into place. The amount of research material we had was enormous, so working through the structure and making sure all the details, foot notes, references were correct was a big part of the work. When we came to the idea of building the whole thing with video and sound it felt right, because it’s so immaterial, but also because it makes a kind of symphonic approach possible. It’s extremely important to have the viewers open up emotionally to the realities behind the stories and not just the cold data.

The text on the webpage of The History of Cattle states that “The exhibition is suitable for scientific, pedagogical or art context.” Would you say that this statement can also be applied to The Museum of Nonhumanity as well?

Since we are appropriating the form of a museum, it makes sense to think of it from the point of view of pedagogy also. We had a specifically tailored outreach program for high schools and upper classes in Helsinki. That said, it’s clearly an art project, built to make you think, not to give you easy answers. But I guess our approach is that art can be pedagogical, and it doesn’t mean that it would be didactic.

Thanks Terike and Laura!

Check out The Museum of Nonhumanity at Momentum 9, The Nordic Biennial of Contemporary Art curated by Ulrika Flink, Ilari Laamanen, Jacob Lillemose, Gunhild Moe and Jón B.K Ransu. The exhibitions remain open in various location in Moss, Norway, until 11 October 2017

The Museum of Nonhumanity is also open in Santarcangelo di Romagna, Italy for the Santarcangelo Festival.

Previously: MOMENTUM9 – “Alienation is our contemporary condition” and MOMENTUM9. Maybe none of this is science fiction.