The Other Side of Silence sounds like an odd title for the mid-career survey of a photographer. The images that Syrian-Armenian artist Hrair Sarkissian makes are silent and yet they tell stories. With their bare interiors, desolate landscapes and their absence of human figures and actions, they make emerge the legacies of conflicts, violent erasures and other collective traumas. Their silence echoes the silence forced upon people around the world who are too frightened to speak out or simply talk about politics.

Hrair Sarkissian, In Between, 2006

Hrair Sarkissian, Unexposed, 2013

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

The Other Side of Silence opened at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht back in November and it’s the most touching and intelligent show I’ve seen these past few months. Sarkissian’s works invite us not to ignore the unspeakable, the overlooked and the invisible. Each image calls for attention, time and deeper reading. This is a bold and urgent request in these days of overexposure to images, relentless crisis and visual exploitation of human suffering.

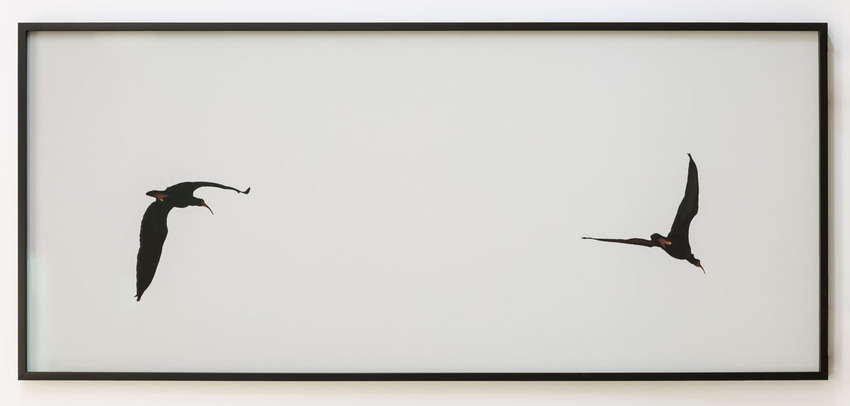

Hrair Sarkissian, Final Flight, 2018-2019

Exhibition overview. Photo Peter Cox for Bonnefanten Museum

Last picture of Northern Bald Ibises. Photo: Oak Taylor-Smith for Factum Arte

Hrair Sarkissian, Final Flight, 2018-2019

The Northern Bald Ibis was once widespread across the Middle East, northern Africa and Europe. Regarded as the ancient guide of pilgrims to Mecca, depicted in the oldest hieroglyphs found and featured in Noah’s Ark, it has had significant symbolic and cultural values in the region for thousands of years. Today, the bird is critically endangered. In Morocco, the wild breeding population counts just over 500 birds. A surviving colony of seven was discovered in the Syrian desert near Palmyra in 2002. The tiny colony was studied and protected until the war in Syria broke out, and then disappeared again around the time Palmyra was destroyed in 2014. The decline in the breeding range of ibises is part of a wave of regional biodiversity loss of iconic animals and plants in the last decades.

In Final Flight, Sarkissian memorialises the seven migrating ibises that were lost or never returned after the Daesh invasion of Palmyra.

The work uses high-res photogrammetry 3D technology, age-old techniques and specimen lent by a Spanish zoo in Andalusia to create sculptures of the Northern Bald Ibis skull, as a testament to the overlooked realities of destruction and migration in the region.

Final Flight also consists of an archival inkjet print of the last photograph of the birds flying over Palmyra, a hand-milled relief on aluminium of the birds’ migration path from Syria to Ethiopia, and a film capturing their route from a bird’s eye view perspective.

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares, 2008

Hrair Sarkissian, Execution Squares. TateShots

The artist was a schoolboy when he saw three hanged bodies dangling in the middle of a public square in Damascus. The image has inhabited him ever since.

In the hopes of overcoming the memory’s hold on him, the artist decided to photograph public squares in three Syrian cities which were historically used for public hangings. Sarkissian’s Execution Squares series shows empty city centres at dawn in Aleppo, Latakia and Damascus. The condemned person is often brought to the square at 4.30 am, their body is left there until around 9 am so that citizens can witness the cruelty of state punishment on their way to school or work.

Execution Squares documents the invisible. There is no visible trace of violence in these images. Yet, once you know the story, they seem to be haunted by brutality and horror.

Hrair Sarkissian, Homesick, 2014

Hrair Sarkissian, Homesick, 2014

Homesick, 2014. Exhibition overview. Photo Peter Cox for Bonnefanten Museum

The two-channel video Homesick shows, on the left screen, a model of an apartment block slowly crumbling under an invisible force. After a few minutes, the structures resemble the aftermath of bombings, eerily evoking the everyday carnage experienced not just in Syria but also in places like Iraq, Gaza and now Ukraine. The construction is the scale model of the Damascus apartment building where he grew up and where his parents continue to live. Like many people of their generation, they refused to leave Syria despite the unending violence.

On the right side of the video installation, the artist, sledgehammer in hand, repeatedly whacks a structure. The camera zooms on his face and upper torso. You assume he is destroying the replica of his childhood home.

The replica serves as a container of memories where nostalgia is intertwined with tragedy. It evokes longing, displacement, helplessness and serves as a proxy for the countless other homes destroyed across the region.

Perhaps the performance had a cathartic effect. Or perhaps, like his parents, he cannot really let go of his life in Syria. The work has a particularly poignant resonance in light of the recent earthquake in Syria and Turkey. It also reminds us that anyone can lose their home and everything associated with it because of a war, an earthquake, financial predicaments, etc.

Hrair Sarkissian, In Between, 2006

Hrair Sarkissian, In Between, 2006

Memory and exile haunt other works by Sarkissian. As a Syrian-Armenian, whose grandparents were forced to abandon their homes in Anatolia under the threat of genocide, Sarkissian comes from a lineage of individuals whose daily life is marked by the melancholy of past landscapes. When he finally visited ‘Mother Armenia’, the artist found it hard to reconcile the family stories with the landscapes and situations he encountered.

The series In Between depict the white snow-filled landscape of the former republic of the Soviet Union. The tranquil blanket of snow covering the abandoned Soviet-style buildings and other austere locations masks a dark history made of war, poverty and genocide. In an echo of the diaspora’s endeared and almost mythological description of Armenia, the scenes resemble stage sets. What does the discrepancy between idealisation and say about how national or cultural identity can be shared across generations?

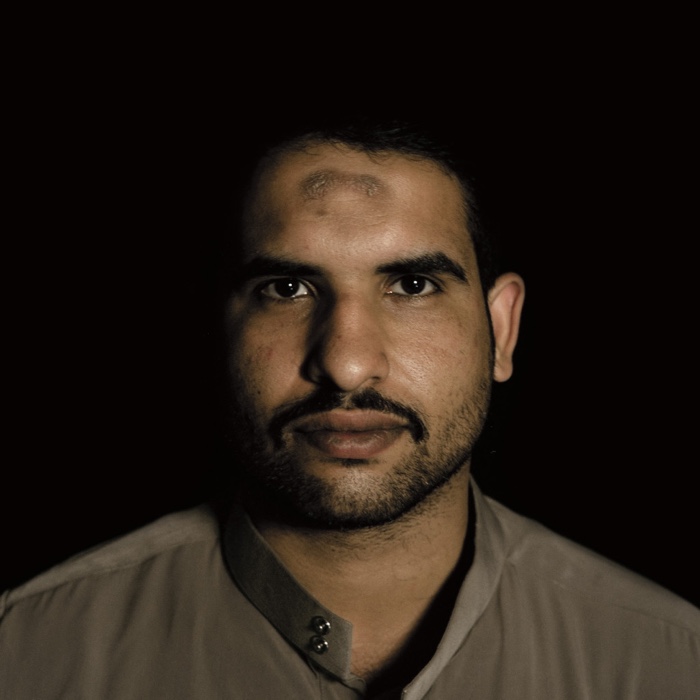

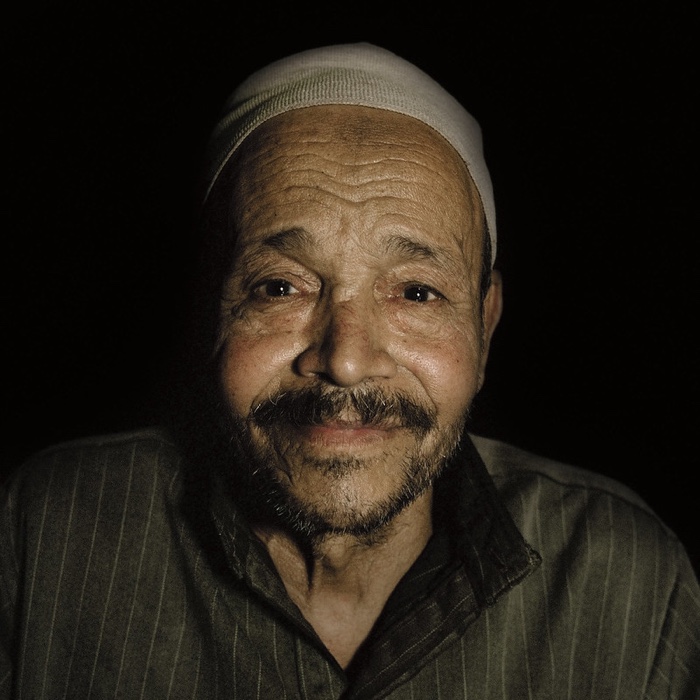

Hrair Sarkissian, Zebiba, 2007

Hrair Sarkissian, Zebiba, 2007

Exhibition overview. Photo Peter Cox for Bonnefanten Museum

Sarkissian seldom takes portraits. His Zebiba series of 45 devout Egyptian men focuses less on their faces than on the prayer scars on their foreheads. Called ‘Zebiba’, the mark on their forehead is caused by the repetitive kneeling on a prayer rug or a Mussallah (Stone of God). On one level, the worshipper aspires to distance himself from earthly culture. However, the desire to become invisible when facing God, makes him stand out as a very pious Muslim within his social environment. Once I noticed the mark, the individual features of each man dissolved and I could only look at the mark.

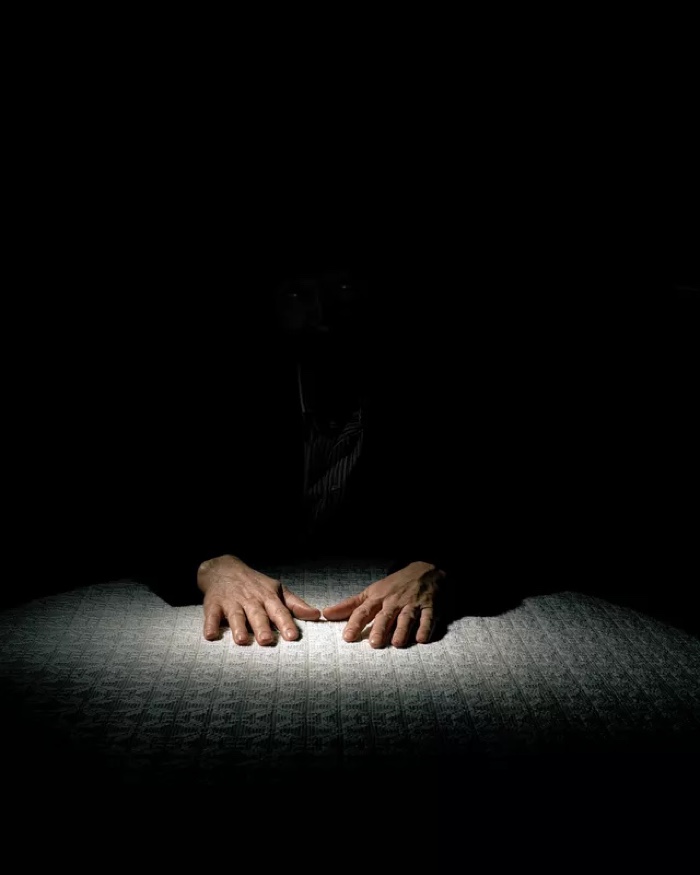

Hrair Sarkissian, Unexposed, 2012

Unexposed introduces us to the descendants of Armenians who converted to Islam to escape the genocide that took place in the Ottoman Empire in the early 20th Century. Today in Turkey, having rediscovered their roots and reconverted into Christianity, these descendants are forced to conceal their newfound religious beliefs or risk further ostracisation. Neither Armenian enough nor Turkish enough, they have to remain shrouded in darkness.

Hrair Sarkissian, Last Scene, 2016

Hrair Sarkissian, Transparencies, 2012

Artist Portrait – Hrair Sarkissian: The Other Side of Silence

Exhibition overview. Photo Peter Cox for Bonnefanten Museum

Exhibition overview. Photo Peter Cox for Bonnefanten Museum

Hrair Sarkissian: The Other Side of Silence is on view until 14.05.2023 at the Bonnefanten Museum in Maastricht.