RAVE. Rave and Its Influence on Art and Culture, edited by art curator Nav Haq.

black dog publishing writes: Rave: Rave and Its Influence on Art and Culture is one of the first publications to critically engage with the historical rave movement of the 1980s and 1990s as it relates to contemporary art and visual culture.

Following the death of industrial Europe, rave emerged as Europe’s last big youth movement. This book considers the social, political and economic conditions that led to the advent of rave as a ‘counterculture’ across Europe, as well as its aesthetics, ideologies and influence on contemporary art and beyond. Combining specially commissioned texts, interviews and factual material, the book represents a broad range of artistic practices, including the work of Jeremy Deller, Rineke Dijkstra, and Daniel Pflumm, amongst many others.

In addition to artistic contributions, the book features texts by Mark Fisher and Nav Haq, as well as interviews with Walter van Beirendonck, the famous Belgian fashion designer; and Renaat Vandepapeliere and Sabine Maes, who run the legendary R&S Records.

Andreas Gursky, May Day III, 1998

Of course i was going to love this book. It features great artworks and insightful essays, it’s beautifully designed, but it also explores a cultural phenomenon i actually experienced back when i was wearing crazy fluorescent bomber jackets and unflattering combat trousers. (And there goes my pretension to write an objective review…)

Rave, that underground cultural phenomenon from the ‘80s and ‘90s, might feel incredibly distant and dated. Yet, as the publication demonstrates, much of what made and shaped the movement find echoes in today’s post 2008 crash society.

Erik Plenge Jakobsen, Everything is Wrong, 1996

First of all, rave provided an escape for those who felt lost in front of the decline of industrialism, the rise of neoliberalism and the erosion of state welfare, it gave them a sense of togetherness, of belonging to an open culture, of eluding formal structures of control.

Then of course there’s the key role played by technology. Rave music explored emerging and existing technologies, at a time when instruments became more affordable, more portable and easier to master without the need of a traditional music education. Technology also gave way to new sounds, new beats, new cut&paste and samplings and even new experiments in subverting historical sonic weapon technology in order to bring people together. Last but not least, the period saw the birth of the internet.

Unfortunately, raves were also the object of police crackdown and governmental attempts to criminalise them (making them even more appealing to young people obviously.) The Mariani Law in France, for example, linked raves to terrorism. Curator and book editor Nav Haq writes that the rave movement was not a political one. Instead, it was politicised through its criminalization by the state.

A Glossary of Rave, as illustrated by graphic designer Jelle Maréchal

As the editor of the book notes, rave remains a fairly under-explored youth movement (it’s been less dissected in studies, exhibitions and literature than punk, for example.) It is both familiar and a bit foreign. The chapter titled “Glossary of Rave” illustrates this point quite easily when it brings together words i wasn’t expecting to find gathered in the same chapter. Some are mainstream today, others are a bit forgotten, all have left marks on contemporary culture: Kraftwerk, Gabber, Haçienda, Belgian Hoover, KLF, Accelerationism, Relational Aethetics, Sonic Weapons, Sonic Weapons, Wolfgang Tillmans, etc.

It probably doesn’t matter whether you raved or whether your mum and dad fell in love and conceived you after yet another rave party, you’re bound to find RAVE. Rave and Its Influence on Art and Culture surprising, informative and highly entertaining.

Quick look at some of the works i discovered in the publication:

Irene de Andrés, FESTIVAL CLUB. Where Nothing Happens, 2013

Festival Club was an unsuccessful big entertainment complex with two stages in Ibiza. After it officially closed, the site was used for clandestine raves in the 80s and early 90s. In 2013, Irene de Andrés went back to Festival Club, found only weeds and rumble and invited one of the most famous DJs of Ibiza’s 1980s nightlife to perform a set of balearic and house with only the decaying structure as his audience.

Cory Arcangel, The AUDMCRS Underground Dance Music Collection of Recorded Sound, 2011-12

From 2011 to 2012, Cory Arcangel’s studio archived almost 900 trance LPs that had been purchased from a 1990s trance DJ. Visitors can listen to the LPS in The AUDMCRS Underground Dance Music Collection of Recorded Sound and read through a booklet containing all relevant data (format, size, speed, generation, etc.) about each record. The project underlines the personal obsession often involved with collecting, as well as Arcangel’s own interest in preserving a cultural history that relates to his work and life. “It is said that the music we hear as teenagers is, and will always be, the most important music for the rest of our lives. For me, this music is techno – the cheap, voiceless, machine-age disco that became popular in the clubs of Chicago in the late 1980s and from there quickly spread throughout the globe” (Arcangel, 2011).

Jeremy Deller, Acid Brass, 1997. Band members warming up on the South Bank, London

The Williams Fairey Band, Acid Brass – What Time Is Love

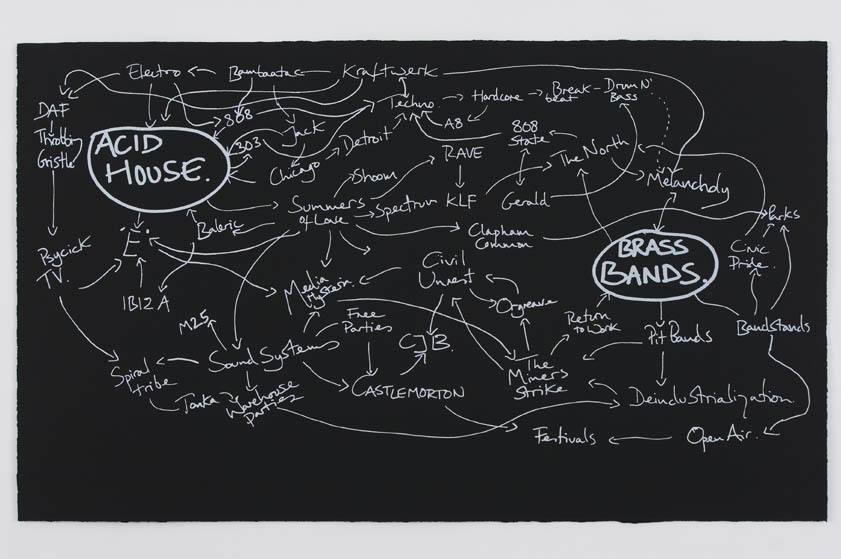

Jeremy Deller, The History of the World, 1997 (image)

“I drew this diagram about the social, political and musical connections between house music and brass bands – it shows a thought process in action,’ said Jeremy Deller. “It was also about Britain and British history in the twentieth century and how the country had changed from being industrial to post-industrial. It was the visual justification for Acid Brass. Without this diagram, the musical project Acid Brass would not have a conceptual backbone.”

Denicolai & Provoost, Nothing, 2005

In 2005, Denicolai & Provoost arranged for police vehicles, fire engines and ambulances to drive around the SMAK museum in Ghent, all siren blasting. The artists were inside the museum, organizing a rave party ‘providing the sense of an illicit event whilst surrounded by the sound of the authorities.’

Mark Leckey, Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore, 1999

Matt Stokes, MASS, Exhibition View at De Hallen, Haarlem, 2011, Photo Gert van Rooij, M HKA Archive

MASS is a sound system that grows in size thanks to donations of speakers and other components from the public. The work is reconfigured differently whenever it is exhibited, acting as a sculptural metaphor for the people brought together in congregation.

Walter Van Beirendonck, Hard Beat collection, 1989-1990 (Exhibition view.) Photo M HKA

Walter Van Beirendonck‘s Hard Beat collection from Autumn/Winter 1989 took inspiration from the Belgian new beat phenomenon and made use of innovative industrial fabrics from the worlds of sport and safety, such as reflective material. Some of the designs in the collection incorporate the Sony Walkman, the 80s symbol of mobile music.

RAVE. Rave and Its Influence on Art and Culture is the catalogue of ENERGY FLASH. The Rave Movement, an exhibition on view at M HKA in Antwerp until 25 September 2016.

Also in the show: Brown Sound Kit. ‘Toilet humour for gallery space’.

I’ve been shouting my love for Walter Van Beirendonck before: Walter Van Beirendonck: Dream the world awake, The Art of Fashion: Installing Allusions (Part 2).