Preppers (aka survivalists, although the two words identify slightly different groups) are training, stockpiling and gearing up for the catastrophe that will lead to the collapse of society or make life on Earth unbearable. A massive ecological disaster, a climate shock, widespread riots, an AI gone rogue, a financial crisis worse than the 2008 one or a pandemic. They might not be sure about it is exactly that will lead to the breakdown of civilisation but they are getting ready for it.

The survivalists range from families who amass food and water supplies in their basement to wealthy individuals who buy bunkers and other fortified properties in remote locations. Prepping is a lifestyle, with its own aesthetics, language and market. Its own fairs and camps even.

Loren Kronemyer, After Erika Eiffel, 2019

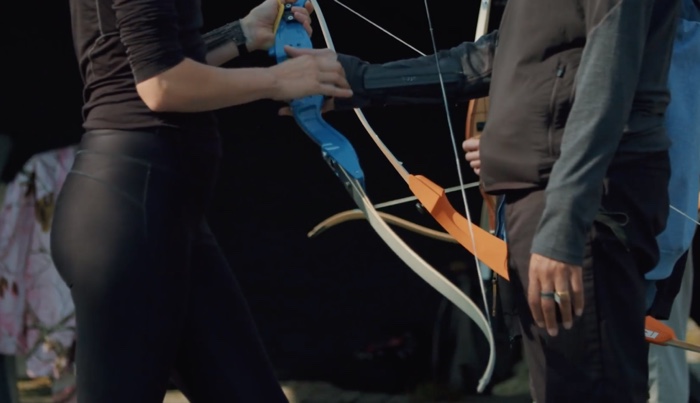

Loren Kronemyer, Training for True Aim, 2019

It’s very tempting to dismiss this community as a bunch of hysterical worrywarts and machos in search of an opportunity to parade their mettle. Loren Kronemyer, however, looks at this subculture with a critical yet open mind. Together with Guy Louden and Dan McCabe, she has curated a series of exhibitions about doomsday preppers. The shows examine the phenomenon as the expression of wider cultural anxiety and a loss of faith in governments capability to take care of their own citizens. They also explore the nuances of a subculture where sustainability and self-sufficiency rub shoulders with paramilitary tactics and unbridled individualism.

The current iteration of the PREPPERS is touring Australia right now.

Video Documentation of the PREPPERS exhibition at the Fremantle Arts Centre in 2020. Video and editing by Graham Mathwin

Loren Kronemyer is an artist living and working in remote lutruwita / Tasmania, Australia. Her works span interactive and live performance, experimental media art and large-scale worldbuilding projects exploring ecological futures and survival skills. As part of duo Pony Express, she is co-creator of projects like Ecosexual Bathhouse, a touring queer sex club for the entire ecosystem. I asked her to tell us more about her work and her view of prepper culture.

Hi Loren! This is already the fourth iteration of the PREPPERS exhibition. Why did you want to work on an exhibition about doomsday preppers? What can art bring to the discussion around the collapse of civilisation?

This exhibition was instigated from a conversation between myself and two other artists, Guy Louden and Dan McCabe. In 2016 we ran into each other at the opening of an art school graduate show in Western Australia, where we lived at the time. We struck up a chat as friendly colleagues, but within the space of a few minutes, our conversation devolved to us ranting about the doomsday prepper forums we were reading and scheduling a visit to the shooting range together. It’s an absurd scene, three comfortably emerging millennial artists, sipping drinks in a gallery while exchanging bootleg survivalist jargon, indulging a dire paranoia under the veneer of our casual social context, but I guess that’s exactly what the “discussion around the collapse of civilization” looked like for us at the time. We decided to continue our conversation through a creative project, teaming up as a collective to curate and produce different editions of this show that has progressed and evolved through several iterations now.

In the discussion of collapse, art is a useful way to create nuance, ambivalence, critique, affirmation and play where dominant narratives are subverted. It’s easy to condemn the toxicity of “prepper” culture: its patriarchal violence, its absurd delusions, its submission to the logic of necro-capitalism.

But at the same time, we all hear the same alarms bells ringing. So we set out to make a show that digs into some of the iconography, jargon, materiality and sensory worlds of “prepper” culture, hoping to satiate our own curiosity and examine some of its bizarre contours. For emerging generations, I think it’s important to foster a nuanced discourse around the possible futures that face us. But I am a very paranoid artist by nature. I abide by the notion of the slow apocalypse: collapse has been happening for a long time and is felt most profoundly by those that don’t benefit from dominator culture. Or in other words, the dudes hoarding luxury bunkers and guns probably know the least about how resilience works.

In making PREPPERS, I approached my body of work with a very selfish methodology. With each iteration of the show, I used my project resources to learn a new so-called “survival skill”, exploring it deeply through research, training and paraphernalia in hopes of achieving some level of expertise, explored through my artistic practice. This has been my pretext to acquaint myself with many skills I was curious about, like water distilling, trap building, marksmanship, etc, honing them through a critical and often collaborative artistic process. By entering a dialogue with these practices, I hope to make space for more people to join in, so we can create our own narratives of collapse.

Guy Louden, Dan McCabe, Loren Kronemyer, E-Waste Barricade, 2019. Photo: Dan McCabe

How has the show (and the public reaction to it) evolved over time?

From a logistics standpoint, the show PREPPERS has always been collectively run. Guy, Dan and I began by working together to curate, fundraise, design, install, document and administrate experimental versions in artist-run galleries in Fremantle, Sydney and Melbourne. We used these iterations as a basis to pitch the show to a major gallery in Western Australia, the Fremantle Arts Centre, who invited us in for a presentation at the end of 2019, at which point we had the resources to involve more artists, including Thomas Yeomans and Tiyan Baker whom I had collaborated with previously on the work Apocalypse Anonymous. We used that platform to pitch the show to ART ON THE MOVE, a regional touring initiative, who had prepared us to tour regional Australia at the beginning of this year. That tour was abruptly halted by the global pandemic. During the shutdown, we received an Australia Council Resilience Fund grant to publish the work as an experimental website, so now there is a digital archive of the work that is, ironically, wholly the product of a global catastrophe. As of today, with parts of Australia opening again, the tour is resuming in a far different context than the one in which it was conceived.

Responses to the work have often been polarized, and I honestly don’t feel like I have a good grasp on the spectrum of responses it’s provoked. Over the last 5 years, this show has always been evaluated based on its grim relevance to current events, but the current events in question are always changing. Although the imagery of the show has been pretty consistent, it resonates differently based on the rapidly shifting baselines of the world we occupy.

When PREPPERS was born in 2016, we were intrigued by observations like the emergence of luxury bunkers and survival gear, the integration of technology to stoke and suppress civic unrest, desensitization towards images of catastrophe and upheaval and the emergence of our own demographic of pseudo-doomer millennials. Through our collaboration and conversation, I have seen myself and the other artists lean further into our own fetishes and connections to the subject matter along the way, allowing the work to grow in scope.

It has been a deeply strange experience keeping this project alive in this moment when the subject matter is so urgent and our individual perspectives so irrelevant. Every human on earth knows more about prepping and survival, whatever that means, than they did six months ago. In some ways, the world needs this show and its ambivalent gaze less than ever, so we will see where it goes from here.

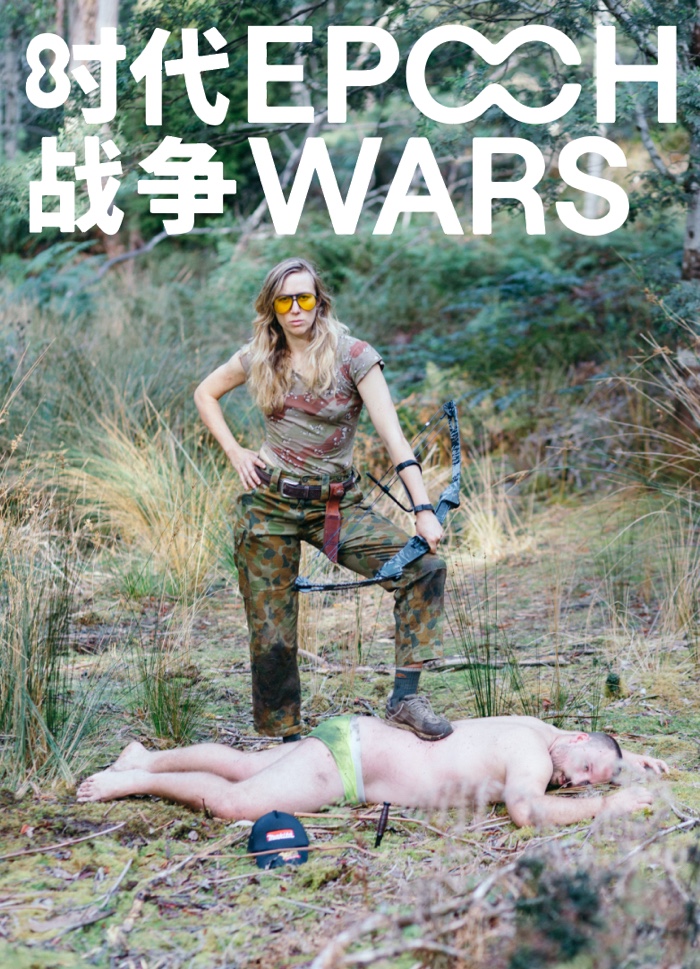

Pony Express, Epoch Wars, 2019. Photo: Julian Frichot

Loren Kronemyer, Wounded Amazon of the Capitalocene, 2019. Photo: Dan McCabe

The only preppers I’ve heard about are in the USA. I think that the prepper movement is growing in Europe too. I know very little about Preppers in Australia though. The history, geography and culture in Australia is very different from the US ones. Are these differences reflected in Australian prepper culture? A different sense of urgency? A different type of anxiety or focus?

I have lived in Australia for the past decade, but because I am from California I have a particularly American inflexion to my experience. The show riffs heavily on the American cultural narrative of prepping as it collides with global culture, Australian contexts, and each of our experiences and interests. For example, Tiyan Baker’s work Bamboo Paradise documents the way that folks in rural Cambodia are exploiting the Youtube trend of survival building channels, a trend that originated with an Australian creator called Primitive Technology who gained viral popularity and seeded thousands of imitators. The way prepping differs for our generation versus previous ones is that we are articulating our ideations collapse through the intricate tool of the global internet.

Though specific dreams and experiences of doom and survival differ from culture to culture, they intersect in uncanny ways. There’s a story about a wealthy Texan who built a bunker in the middle of lutriwita/Tasmania. Fearing the cold war, he pointed at the island on a map, bought up 18,000 hectares of land right in the middle, and built an underground bunker suitable for several families. When he died, the land was eventually auctioned by his estate. In 2013, it was purchased by a historic partnership between the federal government, the Indigenous Land Corporation and Tasmanian Land Conservancy, with ownership passing to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Community and the land dedicated to cultural custodianship. I think that story reflects some interesting collisions between the fantasies and realities of what survival looks like across geographies, generations, and epistemologies.

Loren Kronemyer, After Erika Eiffel

You live in an off the grid situation in Southern Tasmania which I suspect enables you to experiment with self-sufficiency. That’s something that is very appealing, romantic even, to me but also a bit frightening. If a major disaster happened, would it not be safer to be in a city, where you’d get access to more resources, better infrastructures, wider communities?

Having grown up as a city-dweller in Los Angeles, making the transition to this living situation has been a deeply immersive experiment. I am aware that I closely resemble the exact trope I am critical of: that of the delusional American industrialist hiding in my Australian bunkers to escape my hubris. For that reason I try to avoid romanticising living rurally as any sort of grandiose or individualistic world-building project, it’s just another way to deal with this present moment and stay helpful to the processes that sustain me.

In the major disaster of the pandemic, living in lutruwita/Tasmania, an island within an island, has been incredibly advantageous. We are currently COVID-free, but very vulnerable should a second wave breach the island’s borders. Being here during lockdown meant I had access to plenty of space to exist, with most of my basic needs covered by the circular economy of my agricultural region. It took me a long time to come out again and realize that people had resumed doing things. Living out here is a specific aesthetic that doesn’t work for everyone, and it’s not worth valorising. It’s possible to live a more ecologically-conscious, socially conscious lifestyle in the city, where you can take up less space on stolen land and pass around communal resources more readily. I have lost touch with how rustic / not rustic my lifeway here is. Some moments it feels like it’s all muck and blood and fire and leaches, but then other moments I am back to being a millennial sea otter…lazing in bed with my laptop on my belly.

I take pleasure in seeing where my water came from, where my warmth came from and where my food comes from, but I also face the consequences when I don’t look after those things. Every activity has a long tail of energy, planning, preparation, maintenance, patience and consequences in both directions. Before work like this interview can happen, I have do to finish the work of pumping the water, tending the garden, shovelling the shit, acknowledging the worms, gathering the wood, starting the fire, turning the compost, maintaining the balance between my dwelling and the forest. But then again, everyone has chores.

Loren Kronemyer, After Erika Eiffel, 2019

Loren Kronemyer, After Erika Eiffel, 2019

Loren Kronemyer, After Erika Eiffel, 2019

Loren Kronemyer, Training for True Aim, 2019

One of the DIY printable targets you designed for the work Training for True Aim bears the text “Soft skills are survival skills.” That sounded curious to me. I’ve always thought that in order to survive in a disaster situation you needed to be robust, well-trained in hunting or gardening, etc. Maybe you need to know something about medicines or technology but soft skills? What type of soft skills is useful in this context?

Learning these practices has taught me how undervalued soft skills are as survival skills. Skills like communication, negotiation, the ability to self-soothe and self-direct, imagination, humour and sensitivity are all survival skills I’ve had to put into practice for a long time, way more frequently than the more aggressive survival tactics I’ve learned. Survival is a practice that happens in lots of contexts other than acute moments of disaster. For some creatures, cuteness is a survival skill. I have something to learn from all the creatures finding a way to survive the 21st Century.

What attracted me to your work is the contrast between the theme which -in my mind- is quite macho and individualist and the way you communicate it. There is something quite inviting, generous and communal about After Erika Eiffel, Training for True Aim and Apocalypse Anonymous. It triggers interest and curiosity rather than panic. I’ve been wondering what engaging with the wider culture of prepping does to your outlook on life and on the future. Does studying the prepper culture bring more reassurance or more anxiety? More desire to collaborate with others or a drive to retreat?

I am glad that was your reading of my work, because it’s certainly my intention. I work actively to penetrate the macho veneer of survivalism and make space to insert my own queered, pluralist fantasies. I like the versions of survival that we work on together, or that manifest in absurd or improbable ways. Collaboration is always something I am interested in – my collaborations have done the most to benefit my survival, and I am always looking for ways to extend those in new directions.

When I was a kid, I found this book at my grandparent’s house called Back To Basics from Reader’s Digest. This book illustrated homesteading from harvesting logs to building a cabin to weaving a rug, from cooking with methane siphoned from your shitter to butchering a rabbit to baking a pie. This book is totally the product of white American back-to-the-land romanticism, and now I’ve learned that it’s highly sought after among the prepper communities I follow on the web. Anyways when I was a kid I would obsess over this book, thinking that as long as I kept it with me, I had a manual that would help me survive and fashion a life for myself from scratch. Looking back on that, it’s tragi-comic that a feeble Reader’s Digest book encompassed my entire intergenerational cultural inheritance of survival knowledge. It goes to show how crappy the western, colonial, capitalist epistemology is at conveying any meaningful form of ongoingness. I still open that book all the time when I am looking for inspiration, opening to a random page and thinking of ways to apply or pervert the skill it illustrates.

It’s been beneficial for me to make this body of work and realise I’m not alone in my attraction to survival narratives. I think many young folk today are engaging with and rewriting what the future means to us, what our survival story will be. I remember going to dinner at the home of another urban artist my age; when we got onto the topic of survivalism, their partner revealed that they had printed out a prepper handbook from the web and stored it in the ceiling cavity of their apartment. The dominant version of “prepper” culture is not something I get much reassurance from, but it does form a baseline that I come back to again and again for whatever reason, because like it or not it’s a part of my experience.

Loren Kronemyer and Tiyan Baker, Apocalypse Anonymous, 2017. Photo by Julian Frichot

Loren Kronemyer and Tiyan Baker, Apocalypse Anonymous, 2017. Photo by Julian Frichot

Loren Kronemyer and Tiyan Baker, Apocalypse Anonymous, 2017. Photo by Julian Frichot

Loren Kronemyer and Tiyan Baker, Apocalypse Anonymous, 2017. Photo by Julian Frichot

You developed Apocalypse Anonymous together with Tiyan Baker. What is hidden inside these three containers? Do they provide different experiences or outlook on doomsday preppers?

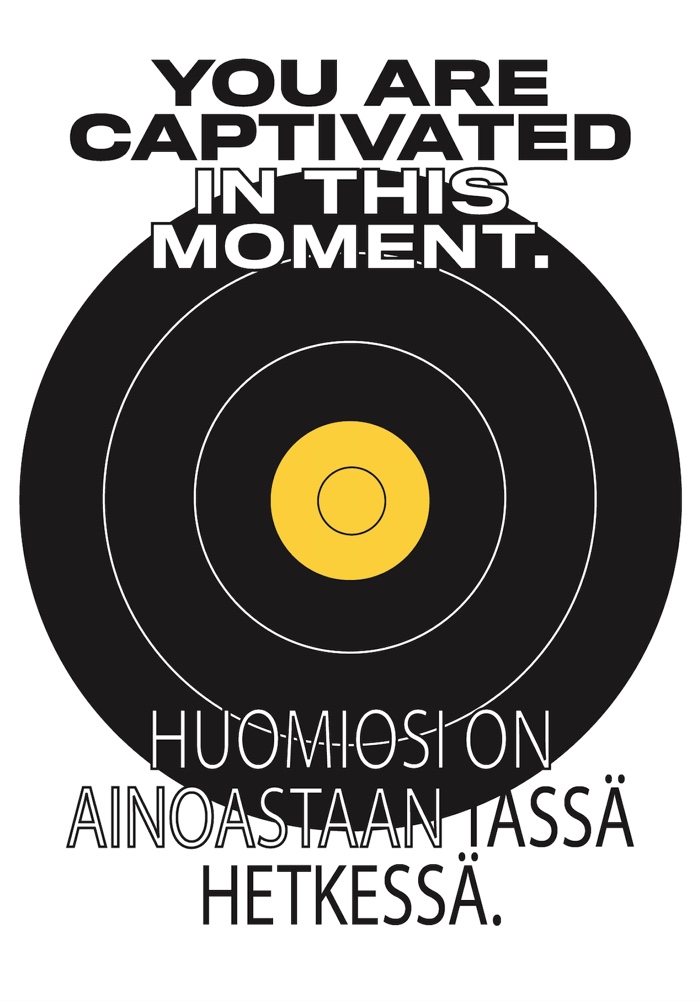

Apocalypse Anonymous is a work that Tiyan Baker and I collaborated on in 2017. It was born from both of us hanging out in both online and offline prepper communities, dialoguing together about our own experiences of ecological anxiety. The work took the form of a public installation consisting of three shipping containers, each one documenting a different approach to processing the end times through first-hand documents we collected.

The first container was set up as an office. Visitors could sit at a computer and scroll through a custom app that harvested content from a combination of message boards, forming this endless scroll that barraged you with videos and posts that ran the gamut of online doomer content. In doomer parlance, any news item trying to spin progress in the face of climate change is derided as “hopium”. The desk itself was studded with arrows, and when you turned around to leave, you’d see that an aggressive hunting bow was aimed at you, mounted above the door. We wanted to convey the feeling of submerging into eco-anxiety through the web, the obsession mixed with the helplessness that comes from experiencing the world’s crisis unfolding through a scroll.

The second container was outfitted as an actual survival shelter. Based on manuals and field guides from emergency services, we filled it with a couple of weeks of essential goods and recommended tools, including food, gas, water, first aid supplies, a bed, radio, maps, et cetera. Tiyan interviewed survivors of a recent severe hurricane here, and their voices played over the radio, describing what that confrontation felt like and how it impacted their state of mind afterwards. It was my first time going through the process of assembling a survival shelter, and it was great to go piece by piece and actually look at each of the rations that were needed. The third container was set up as a sort of big, encompassing nest of twigs and mulch. There were cushions, and it was possible to lay right down in this soft and earthen smelling place. Woven throughout were family photos from the last 50 years, babies and parents and homes, all composted and mulched right in there with you. In that container, we played a soundscape that featured an interview from Glenn Albrecht, an Australian philosopher who is passionate about coining new words to describe the emergent psychological states associated with climate change. He coined the word “solastagia”, which describes the feeling of homesickness or longing for the ecology we used to have, the earth home that doesn’t exist anymore. He recently released a new book called Earth Emotions, which chronicles his whole lexicon of neologisms building on this idea.

Loren Kronemyer, Mangle Tangle Strangle Dangle, 2017. Photo by Dan McCabe

Loren Kronemyer, Mangle Tangle Strangle Dangle, 2017. Photo by Dan McCabe

Loren Kronemyer, Mangle Tangle Strangle Dangle, 2017. Photo by Dan McCabe

Loren Kronemyer, Mangle Tangle Strangle Dangle, 2017. Photo by Dan McCabe

There’s humour in your work too. For example, the baits and traps you designed “to arm the gallery” are threatening of course but the idea of setting traps inside a safe white gallery space is amusing. They evoke typical contemporary art sculptures too. Can you talk about some of these traps? How you made them and what they mean?

I am glad that’s something you appreciate. I am always laughing, even (especially) at my own misfortune, absurdity and capacity for contradiction, and I like to make work that comes from a place of pleasure and play even when the outcomes or subject matter are dark.

The origin was this: browsing through a bushcraft guide, I was taken by the fact that, as you describe, some of the hunting traps looked to me like Alexander Calder sculptures. That was such an imperious and silly thought that I decided to learn to make them, to see how my art school brain would handle it. One of the manuals I read summarized the four principles of trapping as “Mangle, Tangle, Strangle, and Dangle”. I tried all sorts of variations of trap and got most excited by the ones that are held in delicate balance or at high tension.

When setting up traps in a gallery, I like to use as much of the gallery’s existing infrastructure as possible, responding to the architecture and raiding the supply cabinet for rope, hardware, blades and heavy objects to use as counterweights. It’s all very Wile E. Coyote. One of my dreams is to build a deadfall trap out of the false wall of a gallery; I still haven’t figured out the engineering on that yet. The most important parts of the trap are the trigger and the bait, so I pay extra attention to those. In one variation I use a diamond engagement ring as the loop for the trigger, held in balance by a nail and builder’s twine. For bait, sometimes I use books, or solar-powered screens that play videos – you must get right up close and into the snare to view them. I think through each trap’s story based on where I am and what material I am using, but those stories usually stay with me. It helps me think about what traps may surround me, and how to stay vigilant for when I am being baited. Sometimes I am the hunter and sometimes I am the prey, of course.

Pony Express, Epoch Wars, 2019

Any upcoming event, field of research or project you could share with us?

Here in Australia, we are in the process of uncancelling and sometimes recancelling things, so I am surfing that pattern as best I can while also gearing up to plant my spring garden.

The gallery show PREPPERS is resuming its tour through ART ON THE MOVE, going to several places in regional Australia:

August 21 – September 26, 2020: Geraldton Regional Art Gallery

November 9 – December 5, 2020: Katanning Art Gallery

December 14, 2020 – January 13, 2021: Museum of the Goldfields (WA Museum)

May 21 – June 27, 2021: Albany Town Hall

By late August we will have published a new essay from Cassie Lynch, a writer who is researching Noongar memory of deep time climate events, on https://preppers.gallery. We built this website in collaboration with Xavier Burrow to house a virtual version of the show alongside original text from Bradley Garrett (author of the new book Bunker: Building for the End Times) and our COVID first-wave artist video diaries.

I am currently working on writing my first book, which is going to be published as part of an artist book series called Lost Rocks curated by A Published Event. The premise of the series is that 40 artists are contributing short fictionellas that represent the missing rocks on a mineral sampler the publishers bought from a junk shop; my mineral is Copper. I am a huge fan of this series and anxiously polishing my contribution. I have also contributed to a book that is a collective survival lexicon curated by Grace Dennis which is coming soon.

My live art collaboration Pony Express is busy pivoting ourselves all the way into the core of the earth. We have spent the last few years developing the project Epoch Wars, which is an artist-run Geological Congress convened to search for a better name for earth’s present epoch. Epoch Wars is a participatory symposium that eats itself, built of commissions from diverse artists, thinkers and rock doctors who are reclaiming the power to name the geological age we will die in. This work has been researched and developed internationally via research at University of Tasmania, Chronus Art Centre, Artshouse and ASIA TOPA Festival, but our planned IRL versions are on hold and we are currently building a web archive for the project.

We will also be publishing some playful new work and giving a keynote as part of Adhocracy 2020. Adhocracy is an annual artistic development and experimentation platform hosted by Vitalstatistix. In response to the pandemic, they funded 28 original artworks which will be published across 4 weeks in September, as a sort of artistic catalogue meets festival of ideas meets archive of a wild year.

People can stay in touch with me and my projects through www.rubicana.info and www.helloponyexpress.com.

Thanks Loren!

Related story: The Clearing. How to live together when sea levels rise and global economy collapses.