Mainstream media like to tell us how people are getting ready for a post-collapse future. Some buy properties in New Zealand, some go all bunker bliss, others believe that all they should do is escape and colonise another planet (because humans have such a great track record when it comes to colonisation.) Details differ but the spirit is the same: everyone for themselves! Survival of the fittest! Or rather the richest.

Another possibility, albeit a less headline-grabbing one, is that we’ll do what we’ve always done throughout our evolution: we will keep on being a social species, we will cooperate and learn from each other.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

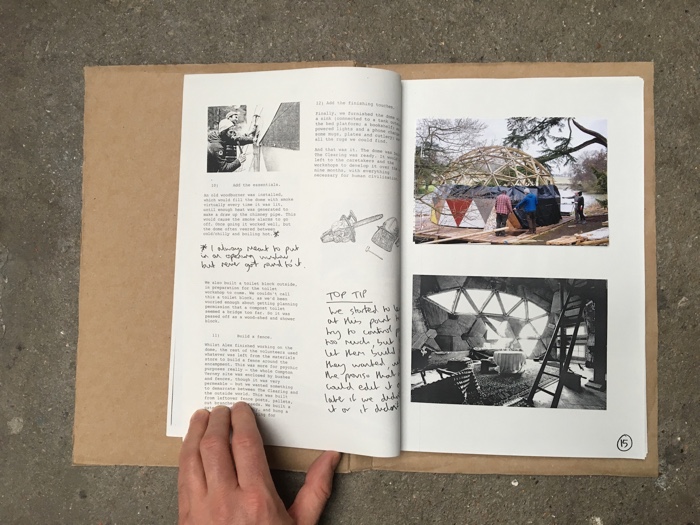

Artists Alex Hartley and Tom James have experimented with the collaborative doomsday scenario. Back in 2017, they built a geodesic dome on the grounds of Compton Verney, an 18th-century country mansion in England. Then they invited members of the public as well as various experts to join them and learn together how we can survive in a world that global warming, economic collapse and political unrest have made alien.

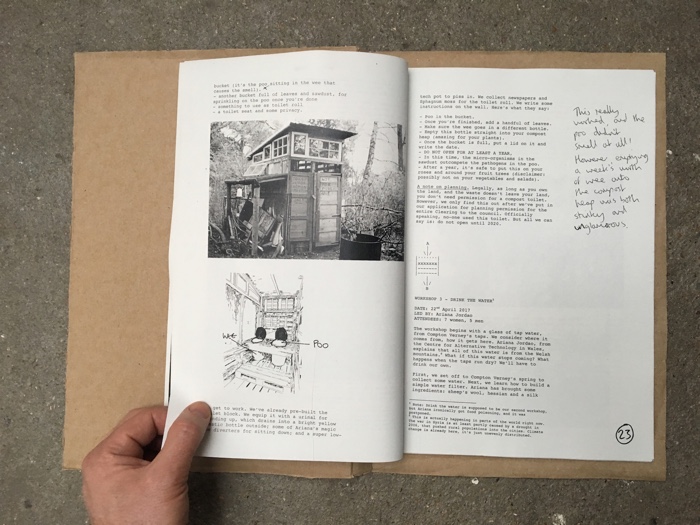

Most of the workshops organised in and around the dome involved learning again the kind of skills that modernity has rendered obsolete: making booze or coca-cola, filtering water, harnessing wind power for electricity, making a foxhole radio, foraging for something edible, finding your way by looking at the night sky, etc. A couple of workshops however, had more ambitious objectives: rebuilding democracy or living and dying.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

The artists wrote a report in the spirit of the project. It was typed on MS Word; printed out and photocopied by hand; and bound in covers made from discarded cardboard boxes. They’ve recently scanned the publication and made it available online for free. From what i could see and read, the low-tech, low-cost, high-collaborative post apocalyptic option is far more enjoyable than the lavish bunker ones.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing. A Report from the Future, 2019

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing. A Report from the Future, 2019

Alex Hartley‘s work destabilises ideas of both iconic architecture and nature by exploring our understanding of utopian ideologies. Tom James creates artworks and publications that aim to change the way people think about the structures, places and ideas around them. I recently got in touch with them to know more about The Clearing:

Hi Tom and Alex! I’ve been encountering more articles and podcasts about preppers and bunker buildings than usual over these past few weeks. They suggest that in order to survive you need to be a hoarder, be afraid and be very selfish. The Clearing offers an entirely different vision of survival. Could you tell us what the project might or might not have in common with these doomsday bunkers in terms of way of thinking about the future?

TJ: From the start, I think we were both really conscious of this understanding of ‘survival’, and wanting to explore the other side of it. There are so many preppers on youtube, always hench guys in full camouflage and wrap-around sunglasses, squatting in a forest and talking in a deep voice about knives or something, into a go- pro. And that whole thing is just so lonely and depressing – imagine actually surviving, on your own, in such a bitter way?

What’s always been interesting to both of us is the other side of the end of the world – could it actually be a chance to live in a simpler, slower way? Could it be good? Chopping wood and building a cob oven and keeping chickens – with other people – is far more enjoyable than sitting on the sofa scrolling through instagram.

AH: I’m assuming the preppers are hugely disappointed that society hasn’t collapsed, like a doomsday cult when their long awaited deathdate passes. The Clearing was always ‘pretend’ – but all the things it did achieve came through the community it built, and the collective learning and endeavour that took place there.

Apart from the geodesic dome, what or who were your guides and inspirations for The Clearing?

TJ: For me, the one big inspiration was Ursula le Guin. Her book Always Coming Home totally changed my life – it’s about a community who live in a valley in what is now California, thousands of years in the future, after some kind of unmentioned apocalypse. It’s this incredible study of their whole (imagined) lives, including their stories and dances and what they eat and what they wear, all told in their words. And it’s good! Really slow and soft and peaceful. It’s the only ‘collapse’ book I’ve ever read where I’d like to live in the community. And I just wanted to carry that feeling into the project, really.

I also think Alex’s work itself was a big inspiration – I remember very vividly standing on the banks of a canal in London in January 2012, looking through the door of the knackered little dome he’d built for his show at Victoria Miro, and seeing this thing that was scruffy and foreboding, and at the same time warm and inviting and soft. That duality about the future really inspired me in all the work I’ve done since – and was what made me get in touch with him and suggest working together for The Clearing in the first place.

AH: Photos of the late 60’s hippy community of Drop City have been pinned on my studio walls for many years. The domes themselves manage to be magically both futuristic and nostalgic at the same time and they seem to carry so much hope for an alternative future. The Drop City story is well enough known that the photos resonate a great melancholy. I always hoped that we could convey some of this naive optimism into The Clearing.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

The Clearing is a wonderful experiment and it looks rather nice. It is less grandiose than the gallery and parkland of Compton Verney though. Was there ever any suggestion that it needed to be glammed up in any way?

AH: We were always very surprised that Compton Verney were happy for the whole encampment around The Clearing to be such a mess. Stores and piles of materials, outbuildings and space for experiments were crucial elements of the work. We would tidy up regularly, but in truth the contrast between the manicured stately home and our much less certain, imperfect structure was the best part of its location. There was some initial discussion about the effect on wedding venue bookings…

TJ: At one point a happy couple actually did come and stand in front of The Clearing in their wedding outfits, during one of our workshops. I suppose it made for a nice apocalyptic shot for their album.

We were very lucky in that the curator Penny Sexton was amazing from the start, in terms of protecting it, and carving out a space for this weird, scruffy thing. We were also lucky that this guy called Nick Molyneux from Historic England was at the interview – he was really into the project, and told us about the history of stately homes installing their own hermit in a cave in their grounds, as a curious folly for their guests to peer at. So there was this real precedent for living in the grounds in this way.

And ultimately, Compton Verney really wanted a ‘talking point’ in their landscape – and what else is there to talk about at the moment but, as Helen Nisbet puts it, ‘the end of this world and the beginning of the next’?

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

I was reading an interview with you and you said “We’ve tried to create a place for people to come to learn how to live in the collapsing world that we think is coming our way.” Are you familiar with the field of collapsologie the “applied and transdisciplinary science of collapse”? It grew quite popular in France but I haven’t heard about that concept (at least not in the “French sense”) being debated so much in the UK. How invigorating and empowering (i wish i could find a synonym to that word!) is your vision of the collapse?

TJ: The thing about ‘collapse’ is that it’s easy to think about it when you’ve got a full belly and gas and wifi – but hard to imagine what it might actually feel like. Even when you’re reading all these things in the Guardian about sea-level rise and extinction and mass migration, on the next page it’s still tennis and luxury watches and Cara Delevinge. It’s impossible to get outside of the world. So I suppose that’s what we were trying to do, to let people step outside the world and feel what a different way of living might feel like, with all the different emotions that entails.

AH: All this seems so much closer now. I’m sure The Clearing would take a very different direction in a post Covid world. I’d not heard of ‘collapsologie’ (or Cara Delevinge), but a large proportion of both of our work involves imagining how we might live in and occupy a world with radically changed priorities. I try to hold onto the possibility that this collapse doesn’t have to be entirely dystopian.

TJ: This is the way you have to see it! That’s the big lesson from The Clearing – you need other people, and you need to make it happen for yourselves. I read a thing somewhere translated from French once, which I’ve never been able to find again, called ‘Another End of The World Is Possible’. And that’s just it – don’t believe the apocalypse porn! Don’t let them tell you it’s going to be like The Road! It’s also going to be a chance to build a new, better, slower world in the ruins of the old. It’s not like there’s going to be much else to do, anyway.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

The Clearing also involved a series of workshops around themes as diverse as soap, rebuilding democracy, growing food, keeping chicken, building a toilet or how to die in the future. Now that we’ve had 2 full months of living a life we were not prepared for, do you feel that there are workshops in there that make more sense than others in the current circumstances? Or new workshops that should be organised because you might now have realised that new problems have emerged during this pandemic?

AH: Self-sufficiency for me – or self-reliance. Definitely how to survive in your own company.

TJ: I think this links to the last question in a way – we’ve all still got running water, there’s still food coming into the shops (from whichever mysterious place it comes from) so we’re not quite in the collapse yet. But what it’s shown we do need is better ways to come together and talk and agree to act – and to avoid going down the route of stockpiling and hoarding. The Rebuilding Democracy workshop is really the most valid, I think.

The really interesting thing about this pandemic is that it’s shown that all the things we were told were facts of life (austerity, cuts, long lines of toxic cars with one person in them, cheap flights to weekend break destinations) were all actually choices – and that the government, and by extension society, can make different choices if we think it’s necessary.

I think what we really need now is workshops on community organising and local power, so we can carry on these discussions, and make sure we put alternatives in people’s heads and in their hands. I don’t want to go back to normal, normal was shit.

The Clearing was located in a park. Could a similar project be implemented in urban areas? Do you need this distance from the crowd? Wouldn’t you have access to more resources in a city?

AH: The question of where to make The Clearing was always a huge one for us both – some of this revolved around where we could find the production budget, but also how ‘real’ to make the experience. The first dome I made in 2010 went to Occupy after its initial incarnation as part of an artwork. It immediately created a hierarchy of architecture amongst the soaking-wet tents (it rained non-stop and the dome was waterproof). It was intended to be used as a group meeting space, but quickly became a shelter/drug taking space – underlining separate issues but undermining the solidarity of the Occupy camp. Undoubtedly the project could be much more ‘real’ in an urban setting, but it could also so easily lose any experimental nature and quickly become social support.

TJ: I think it needs to happen in the city! It would be a lot harder, of course. It’s much easier to build a vision of the future in the countryside – you have fuel, water, space, and it’s easier to get rid of your compost toilet, etc etc. But at the same time, it’s probably more urgent to try to build it in a city. At the start of the pandemic, I think the thing I was most worried about was people losing faith in ‘society’ and starting to steal food, etc. If you can help people in a city to believe in each other, to rely on each other and build structures we might need – for instance, turning food waste into cooking gas, and cooking communally – it would probably be a lot more useful long term.

Apologies for the probably very stupid question but why did you call it The Clearing?

TJ: No such thing as a stupid question. It’s partly because that’s what it is – a clearing in the woods – and partly from a book by Wendell Berry, called ‘Clearing’. It’s a book of poems about a piece of land, and staying where you are, and the power of that, and it just moved me. His poems are very much like the ones the people write in Always Coming Home, to be honest.

Alex Hartley and Tom James, The Clearing, 2017

What is the state of The Clearing dome now? Who looks after it?

TJ: It was only ever going to be in Compton Verney’s landscape for three years. We both wanted it to be useful afterwards, so we organised an open call to give it away to someone who wanted it, provided they had the land for it, the people to take it down, and a non-commerical use for it (no glamping). In the end Compton Verney were keen it stayed in the local area, so it went to a branch of the scouts in Coventry, to use on their campsite. Hopefully it will still be there in a few years, rotting into the landscape, becoming something completely different.

AH: I went up for to disassemble the structures with the scout volunteers, and to explain how it rebuild it. We got the dome down and loaded into a truck in an impressive two days. We’re so distanced from the building experience by modern house building techniques, that making a decent size shelter with only hand-tools and a few ladders is a super satisfying collective achievement.

Have you heard from the caretakers or from the participants to the workshops since the coronavirus lockdown?

TJ: Yes a few of them – lots of people are thinking about it, now that we’re all outside the world in some way. I think quite a few people who couldn’t really imagine ‘the future’ before are now seeing The Clearing in a slightly different light. There were also quite a few people asking to do some sort of on-line reading group with the book we made, which, as we only made 500, was quite difficult. Hence the idea to scan it and put it online. Hopefully it will be helpful or useful or interesting, in some way.

Thanks Alex and Tom!