Back in 2006, I discovered Eric Maillet’s Art Criticism Generator in an exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo. As its name suggests, the work consisted in an automated art critic delivering statements supposed to comment on artworks. The sentences produced were slightly preposterous but not more than many of the texts that people working in the art world write. Because I’m short-sighted and maybe also a bit vain, I laughed and dismissed the suspicion that one day a piece of software will be a far more competent art critic than I am.

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon and Pierre Cassou-Noguès, Welcome to Erewhon, 2018-2019

Julien Prévieux, Where Is My (Deep) Mind?, 2019

Peter Buczkowski, Twitch, 2018

Dasha Ilina, Center for Technological Pain, 2017-now. Photo by Yiannis Colakides

Two years ago, I had an opportunity to further reflect on the obsolescence of human cognitive labour and on the near ubiquitous use of machines in the workplace when the NeMe Arts Centre in Limassol (Cyprus) kindly invited me to curate an exhibition about the impacts that digital technologies are having on labour practices. We devised the exhibition, the pandemic delayed its opening for a year but it is now open to visitors if ever you find yourself in Cyprus. Just be quick, it closes tomorrow evening!

If you’re curious about the ideas and questions that guided the show, there’s a curatorial text on NeMe’s website. There’s also a video where i talk about the exhibition but because I’m vain (see above), i’m not going to link to that one: it was 36 degrees in Limassol that afternoon and electric lights were pointed at my liquefying face.

I’d rather talk about the artworks anyway. They looked at issues such as the translation of cognitive tasks into lines of code; the daily life of the invisible -or rather invisibilised- online workers; the transformation of labour conditions in the creative sector through precariousness and the atomisation of tasks; the body of workers disciplined to act like machines; the ways workers can fight back with not just resistance but positive alternatives, etc. I’ve already mentioned Pippin Barr’s It is as if you were doing work last week. Here are the other participating artworks:

Liz Magic Laser, In Real Life, 2019

Liz Magic Laser, In Real Life, 2019. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Nicos Avraamides

Liz Magic Laser, In Real Life, 2019. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Nicos Avraamides

In Real Life is a reality show installation that follows five creative freelancers from around the world as they try to navigate the gig economy. From an online content creator in Liverpool to a designer in Pakistan, the cast members have been hired to produce the show. Each “episode” follows their journeys as they go through a “30 Day Biohack Challenge” where a tech-savvy life coach and a psychic advisor help them improve their work/life balance.

In Real Life questions online platforms’ promises of “empowerment”, flexibility and freedom. Freelance workers are pressured to provide maximum efficiency at any time and at any cost. They are stressed, overworked and deprived of the comfort of any safety net and social benefits. Furthermore, the use of “biohack” tactics like meditation, yoga, time-management techniques and other optimisation tools suggests that the problem is not the quantity or quality of the work, it’s the worker’s own inability to deal with it.

In Real Life explores the downsides of the gig economy for freelancers of the creative sector but it also shows how people living in developing countries might benefit from platform capitalism as they enable them to earn incomes that are higher than the ones they would normally get in their own countries.

![]()

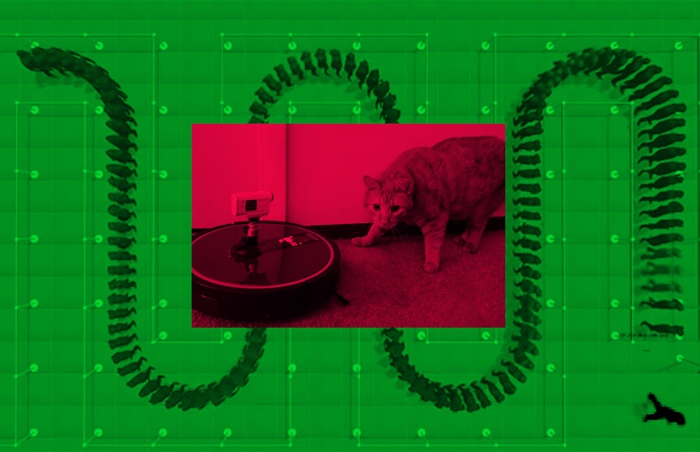

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon and Pierre Cassou-Noguès, Welcome to Erewhon, 2018-2019

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon and Pierre Cassou-Noguès, Welcome to Erewhon, 2018-2019

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon and Pierre Cassou-Noguès, Welcome to Erewhon, 2018-2019. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Helene Black

Stéphane Degoutin, Gwenola Wagon and Pierre Cassou-Noguès, Welcome to Erewhon – Chapter 5: «The Blissful Ones»

Welcome to Erewhon is a series of 10 video episodes that evoke a society where automatisation has been taken to the limit and work as we know it has disappeared. The work alludes to Samuel Butler’s 1871 novel in which the inhabitants of Erewhon, discovering that machines evolve, and evolve faster than biological beings, decide to get rid of them. They destroy all their machines. 150 years later, Samuel Butler returns to Erewhon. Not only are the machines still here, they now take care of everything: industry, agriculture, leisure, transportation, safety… Even society. Everything runs smoothly. Humans are frolicking under the benevolent gaze of machines. Yet there is something uncanny about the whole situation.

Welcome to Erewhon, created by artists Stéphane Degoutin and Gwenola Wagon in collaboration with philosopher Pierre Cassou-Noguès, builds up an eerie narrative using images circulating on the Internet. Cats on Roombas, automated conveyor belts, plush robots taking care of the emotional needs of the elderly, etc. I loved that the work is bold enough not to take the usual dystopian route. Instead, Welcome to Erewhon manages to be critical while presenting the utopia of a world (flawlessly?) run by machines.

Sanela Jahić, Uncertainty in the Loop, 2020. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Helene Black

Sanela Jahić, Uncertainty in the Loop, 2020. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Nicos Avraamides

Uncertainty in the Loop responds to the fear that everything -including creativity, flexibility, imagination and other skills often associated with the profession of artists- can be turned into data and automated. Should artists feel threatened by The Next Rembrandt or by AIs that compose music? Or is there something intrinsically uncomputable in the artistic mind?

In Uncertainty in the Loop, Sanela Jahić converted all her artistic works, research and interests of the past years into data. Each artwork, each creative decision, each area of research was turned into rows of digits. The artist then delegated the decision-making process to a predictive algorithm. The machine identified patterns in the dataset in order to forecast the content and aesthetics of her next artistic endeavour.

To avoid reducing the final work to a mere algorithmic assemblage of existing data, the artist entered her ongoing investigations into the dataset: every word from every text she read was transmitted to the machine and added an element of novelty.

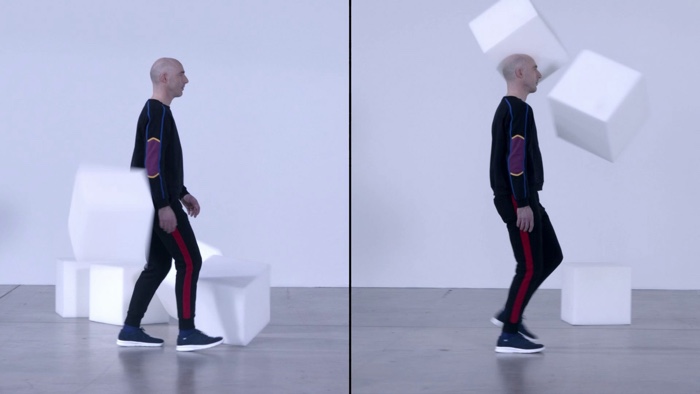

Julien Prévieux, Where Is My (Deep) Mind?, 2019

Julien Prévieux, Where Is My (Deep) Mind?, 2019

Julien Prévieux, Where Is My (Deep) Mind?, 2019. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Helene Black

The video Where Is My (Deep) Mind? translates invisible digital processes into actions that are executed by four performers. Processes that usually take place in neural networks and are only generally perceptible via interfaces are staged inside a test site. The performers embody various experiences of Machine Learning, fleshing out a range of automatic learning processes, from the identification of sports moves to sales techniques. In a “world smartification” culture, these are the types of gestures that get increasingly delegated to the machine.

The video is entertaining thanks to the quirkiness of the gestures and the absurdity of the texts and movements. But it is also eye-opening: it gets you to reflect on how human thinking can be translated into patterns and mechanisms that machines can imitate.

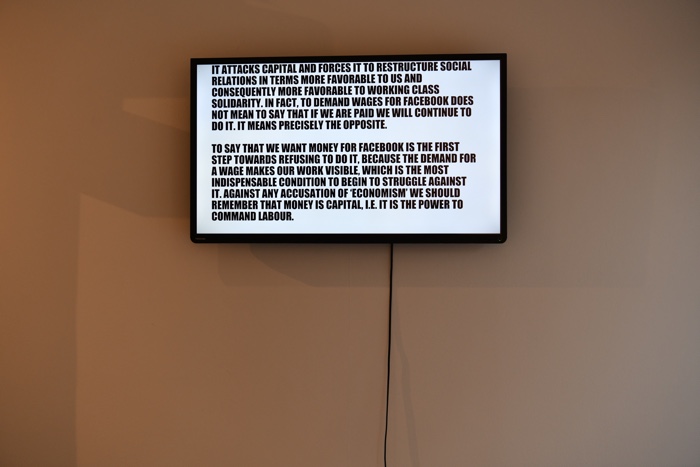

Laurel Ptak, Wages for Facebook, 2014. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Nicos Avraamides

By calling people’s attention to the way Facebook (and other social media sites) is using its customers to do unpaid microwork, Laurel Ptak‘s Wages for Facebook manifesto gets even closer to our daily life.

Drawing upon ideas from a 1970s feminist grassroots campaign Wages for housework that demanded a critical examination of the relationships between capitalism, class and affective labour in the home and outside, the manifesto website Wages for Facebook looks at how these same relationships play out in the context of social media.

Launched in early 2014, the site quickly drew thousands of visitors and international debates about worker’s rights and the very nature of labour, as well as the politics of its refusal in our digital age.

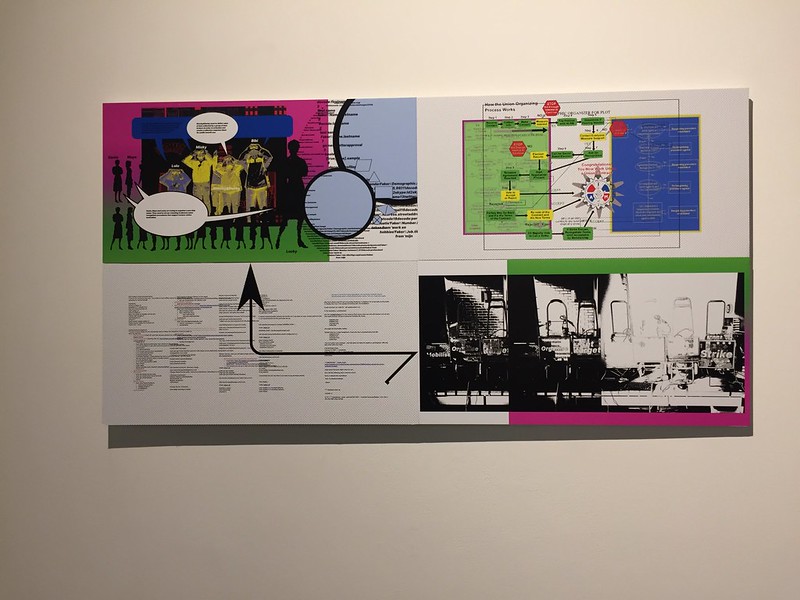

Larisa Blazic , Data Union Fork: Tools for a Data Strike!, Photo by Helene Black

Larisa Blazic went beyond the critique of online platforms and the way they profit from our personal data. Her Data Union Fork looks at how people can reclaim individual data rights and establish collective ownership over data. The art project is building on the OS, blockchain-based, operating system and nodes for decentralised ownership and control of data that was developed by the DECODE project at Waag.

Through public engagement workshops, the broader public was given an opportunity to gather and devise rules, examples and scenarios that attempt to respond to questions such as “What does it mean to strike in the digital domain? How can citizens mobilise and organise for collective action?”

The posters in the exhibition visualise possible tools for engagements and participation of the public.

For me, the project is a kind of 21st-century form of Luddism where you don’t smash the machines (how could we smash them when we rely on them for almost every aspect of our personal, social and professional life) but you look for strategies to reinvent their dynamics and encourage solidarity, community, mutual aid and agency.

The 2 following artworks engaged directly and indirectly with the realities of 21st century’s factory work:

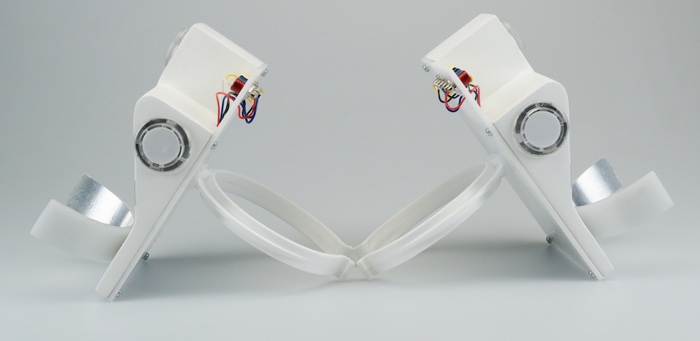

Peter Buczkowski, Twitch, 2018

Peter Buczkowski, Twitch, 2018. Installation view at NeMe. Photo by Nicos Avraamides

Twitch sends small electric shocks to the players in order to force them to play a computer game perfectly. The computer plays a particular version of the game ”Snake“ automatically where an algorithm calculates if the next move has to be up, down, left or right. The computer then sends signals to the two controllers. Each controller can receive two different signals. When a human is connected to them, each signal lets a different finger twitch and unwillingly press one of four possible buttons. The user is thus fairly passive but without this human element, the system would not work.

The work evokes, in a playful way, the alienation of work, the gamification in the gig economy but also the working cultures that are turning workers into robots (work in Amazon warehouses, gig economy, etc.)

Lisa Ma, Farmification, 2012

In 2012, artist and designer Lisa Ma went to live in a joystick factory located in one of the suburbs of Shenzhen. She spent several weeks with the factory workers, sleeping in dorms, sharing their meals in the canteen, making friends. Because most of these young factory workers come from a farming background and because joysticks were at risk of becoming obsolete at the time, she proposed to the factory owners that they’d allow the joystick makers to work part-time in a nearby farm. She called the experiment Farmification, using farming to keep the factory community together when work dwindles. These workers, Ma explains, “are at the fringe of the innovation cycle. They are at the brink of being left out from demand for the products that they manufacture. They are an emerging group of people designed out by technology.”

The work not only challenges some of the Western stereotypes about factory line workers in Asia, it also explores the consequences of a society where young workers leave their farmlands in droves to manufacture our technology gadgets. As a result, food imports are at record highs.

Dasha Ilina, Center for Technological Pain, 2017-now. Photo by Helene Black

Dasha Ilina, Center for Technological Pain, 2017-now. Photo by Yiannis Colakides

Dasha Ilina, Center for Technological Pain, 2017-now. Photo by Helene Black

Dasha Ilina, Center for Technological Pain, 2017-now. Photo by Yiannis Colakides

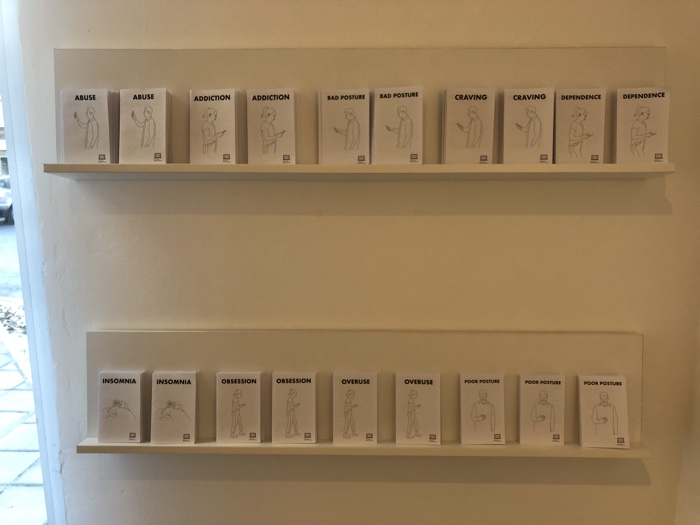

Finally, Dasha Ilina‘s Center for Technological Pain evoke the physical sufferings caused by our daily interactions with digital devices. Physical miseries that lockdown made even more severe. Many of us suddenly found ourselves stuck at home, chained to our laptops and sitting on chairs that did no good to our postures.

Center for Technological Pain is a mock company that offers DIY, open source, super low-tech solutions to relieve the physical discomforts caused by the daily uses of digital technologies. The objects in the exhibition present just a part of the whole collection and they propose solutions to free up your hands, reduce eye strain and prevent finger friction. In addition to these physical solutions, the centre also proposes self-defense moves against technology–a set of tactics of resistance against our own digital aids. Or the ones of your friends. Leaflets were available for visitors to take away and practice the moves at home.

The Working towards our own obsolescence exhibition is on view at the NeMe Arts Centre in Limassol, Cyprus, until 30 July 2021.

Previously: Interview with Pippin Barr, maker of witty and infuriating video games, Augmented Exploitation. AI, Automation and workers who fight back, The Cost of Free Shipping. Amazon in the Global Economy, AJNHAJTCLUB, a celebration of migrant workers, etc.