Machines were supposed to free us from efforts. So why do we find ourselves in a situation where algorithms and electronic devices have made it possible for work to reach us wherever we are, at any time? We are expected to be as efficient, indefatigable and available as robots. Out of Office. This isn’t working for us, curated by Marijn Bril at IMPAKT Centre for Media Culture in Utrecht, presents artistic responses that expose and reject the exploitative drive towards productivity.

Artists are usually well-versed in the practice of being milked, overworked but also of being disobedient. The works selected in the exhibition challenge the rules and conventions that govern the workplace. They subvert the mandate to perform – in the sense of successfully carrying out desired tasks but also in the sense of acting, uncovering opportunities for critique and resistance.

In the modern workplace context, doing nothing, not showing up or demonstrating mutual support become acts of resistance against a system that prioritises profit and optimisation. How do we extend such resistance to foster collective action and solidarity?

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us is small but sharp and full of humour. Here are some of the works I found particularly interesting:

Adrian Melis, The Value of Absence. Excuses to be absent from your work center, 2012

Adrian Melis, The Value of Absence. Excuses to be absent from your work center, 2012

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

Cuba’s socialist system has led to dissatisfaction in the workplace. Wages are low and disenchantment with the socialist economic model has grown.

Adrian Melis offered public servants money in exchange for their excuses. He asked them to record the phone calls they made to their boss to justify their absence. For each excuse, Melis paid the worker an amount equal to what was deducted from their salary for being off work. People received exactly the same amount of money as the state would have paid them for being productive, but without them having to perform any productive tasks. The more people he convinced to stay home, the more interesting his own work became.

Melis documented hundreds of recorded telephone calls. Some of the excuses not to turn up for work were quite creative: kicked by a horse, imprisoned for negligence, attending a Santería ceremony by the sea, dealing with the robbery of a television, a pressure cooker that exploded, a wall that has fallen in the house, a pregnant girlfriend, etc. Collectively, these calls are a testimony of apathy in communist Cuba.

All excuses were paid after the completion of the absence period.

Pilvi Takala, The Trainee (video still), 2008

Pilvi Takala, The Trainee, 2008

Pilvi Takala spent a whole month as a marketing trainee at the accounting firm Deloitte. An expert in bold social experiments that make you uncomfortable, the artist wanted to find out how her new colleagues would react if she did absolutely nothing at the office.

We see her seated at her empty desk in an open-plan office space or at the tax department library. She stares into space and doesn’t seem to engage in any work activity. When a co-worker asks what she is doing exactly or if she needs a computer, she says she is doing brain work. Another time, she spends an entire day inside an elevator, “just to travel a little”. She doesn’t even press any button, which puzzles the other employees.

Her co-workers start avoiding her, they also whisper behind her back. In the email correspondence and phone messages collected as part of the artistic intervention, the other workers describe her as scary, weird or “with a glazed look in her eyes.”

She doesn’t perform the usual gestures expected from her. Pretending to be busy while actually checking your social media pages is acceptable. Thinking and not appearing to do anything else is not.

“Whether accepting my behaviour or not,” Takala explained in an interview, “I forced my co-workers to reconsider their expectations of shared rules and I think the same happens to people who see the documentation as my art piece. After several months, when everyone at Deloitte had already forgotten about the weird trainee and the project was revealed, many felt relieved that it had just been an act; some respected the fact that I could sustain so much social pressure.”

The Trainee has been produced in collaboration with Deloitte, only a few people knew the true nature of the project.

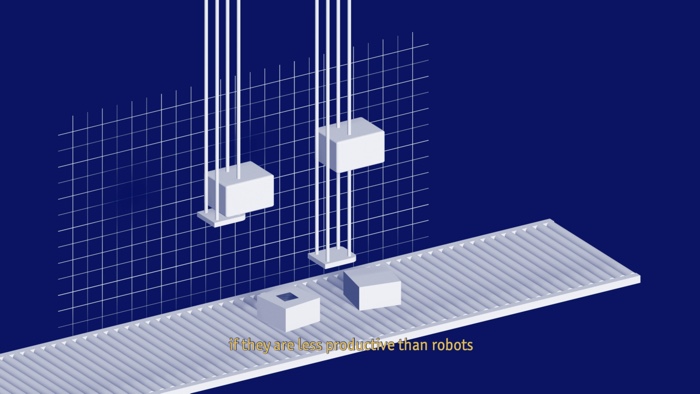

Tytus Szabelski, Lights-Out Factory, from AMZN, 2018–2021

Tytus Szabelski, Amazon Street (Process of Self-De-Colonization), from AMZN, 2018–2021

In December 2018, Tytus Szabelski got a job at an Amazon fulfilment centre near Poznań, Poland. He wanted to observe one of the biggest companies in the world from the inside, on a micro-scale. Both the time and the place were important: it was the peak of pre-Christmas orders and Poznań hosts one of the most active trade unions in the country.

His objective was to shed light on the functioning of the internet giant: the footprint of the huge warehouses, the working conditions, the corporate culture and Jeff Bezos’s visions of the future.

The video Lights-Out Factory challenges the Amazon myth that work at the fulfilment centre is machine-assisted. In reality, humans compete with the machines and their workload is brutal and repetitive: they spend the day offloading and uploading trucks, unpacking pallets, shelving products, picking up products, packing orders, etc.

Local authorities support multinational corporations investing in their areas by not only granting them tax exemptions but also naming streets after them – elevating companies to the level of local heroes. Emmanuel Macron even went further last month when he decorated Bezos at the Elysée Palace with the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest order of merit.

Szabelski perceives the practice of naming streets after corporations in some cities as a form of self-colonisation. His Amazon Street (Process of Self-De-Colonization) counters this tendency symbolically by removing the Amazon Street sign from its location in Kobierzyce (south-western Poland) and presenting it in the gallery space.

The third part of the work included in this exhibition is the online archive Amzn.vnlab.org which documents, among other issues, the other side of today’s labour condition: the people who resist with union leaflets and gestures of solidarity.

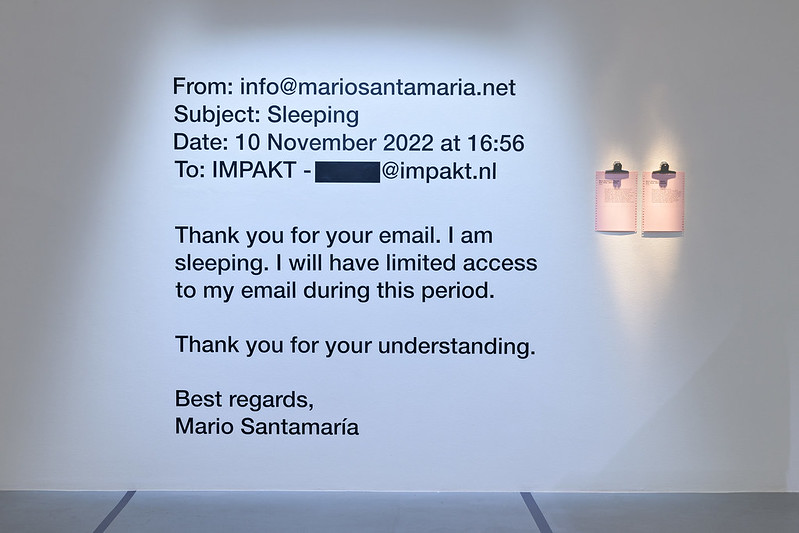

Mario Santamaría, Auto Sleep, 2016–ongoing. Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

I remember the first time I receive an email from Mario Santamaría. I had contacted him to ask if he had time for an interview and in return, I got a message that said ‘Thank you for your email, I am sleeping. I will have limited access to my email during this period’. It was the automatic ‘out of office’ email, only without any hypocrisy (after all, aren’t we all expected to be working even when we are travelling or relaxing these days so why pretend you won’t read that message on time?) and with a subtext that champions passive resistance as a strategy to reclaim free time and resist the current 24/7 availability.

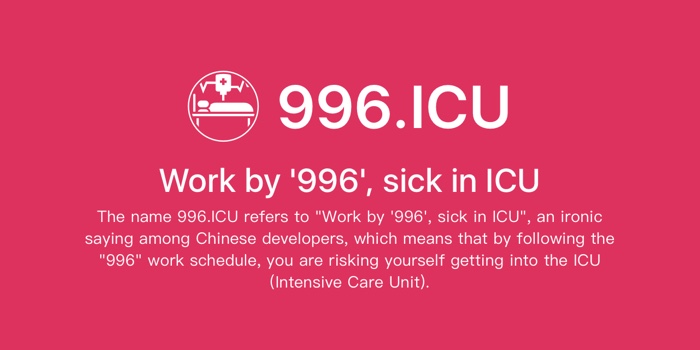

996.ICU, 2019-ongoing

Launched in 2019, the online protest 996.ICU amplifies the growing resentment against the gruelling working hours in China’s tech industry. The 996 work schedule—that is 9am to 9pm, six days a week—has been defined “a blessing” by Chinese tech tycoons. The model has a detrimental effect on the physical and mental well-being of the workers. The project page on GitHub lists the tech companies that do and do not use a 996 work schedule. It also enables programmers to implement the anti-996 license in their code. This means that any company using the software has to comply with a 955 work schedule and pay their employees for overtime.

Sam Meech, 8 Hours Labour – Limited Term Appointment, 2023

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

8 Hours Labour – Limited Term Appointment is a machine knitting performance that brings together a reference to the textile industry of the industrial revolution (and the workers’ fight to have better working conditions in the 19th and 20th Centuries), the 8-hour work day movement and the exploitative culture of cognitive work, in particular in academia. Over the course of 8 hours, Sam Meech knitted a banner with the words ‘8 Hours Labour’, using a hacked domestic knitting machine. In the banner design, he incorporated data from people working in academia showing the work they do beyond a typical 8-hour day contract. The banner is accompanied by two videos – the first documents the ‘artistic labour’ involved in producing the banner in the artist’s studio. The second video shows the artist clearing his office at Concordia University, Montreal, having terminated his LTA (Limited Term Appointment) teaching contract early due to burnout.

More images from the exhibition:

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us. Exhibition view at IMPAKT. Photo: Pieter Kers

Out of Office. This isn’t working for us was curated by Marijn Bril. The exhibition is at IMPAKT Centre for Media Culture in Utrecht until 10 April 2023.

Also part of the exhibition: Hardly Working: Are we the NPCs (non-playable characters) of our own system?

Related stories: On the obsolescence of cognitive and creative labour, An exhibition about labour: can we still want it all?, Err (or the creativity of the factory worker), a conversation with Jeremy Hutchison, Augmented Exploitation. AI, Automation and workers who fight back, Crises of labour, language and behaviour. An interview with Jeremy Hutchison, etc.