Final notes from my visit of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Grounds at MUDAM in Luxembourg:

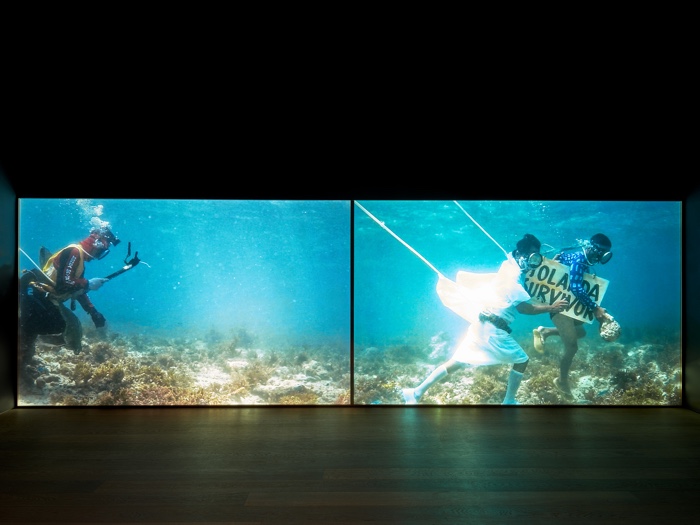

Martha Atienza, Our Islands 11°16’58.4_N 123°45’07.0_E, 2017

Martha Atienza, Our Islands 11°16’58.4_N 123°45’07.0_E, 2017

Hayoun Kwon, 489 Years, 2016

National parks, reserves and other forms of sanctuarization of ecosystems are often used as a measure to protect natural territories from the detrimental impact of human activity. No Man’s Land brought together artworks that explore this issue and invite us to re-examine our relationship with the natural world.

I mentioned some of the works exhibited over the past few days (On thrombolites and other victims of human folly and Arriba! A tropical time capsule in Antarctica) and i wish i’d have been able to do a proper review of the show earlier. No Man’s Land closed last Sunday. It was small but dense with ideas, moving pleas and incentives to rethink the way our (short-term) economic and political interests slowly consume the only planet we have.

Some of the videos and installations exhibited offered surprisingly convincing remedies to our environmental woes, others confronted us with a poignant portrayal of the consequences of our disconnection from the rest of the living world.

Hayoun Kwon, 489 Years, 2016. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

Hayoun Kwon, 489 Years, 2016 (excerpt)

It has been estimated that would take 489 years to demine the Demilitarized Zone that separates North and South Korea.

489 Years is animated film based on the testimony of a former South Korean soldier who used to be stationed in the D.M.Z. We’re thus literary in No Man’s Land territory. Since only authorized personnel can enter the DMZ, Hayoun Kwon uses animation and the soldier’s memories of his patrols to reconstruct the space.

Over time and in the absence of human activity, nature has taken over inside the forbidden space. Between the guard towers, the fences, the barbed wires and the walls, there are streams and hills as well as animals and plant species that thrive in the strip of land that that divides the Korean Peninsula in two.

The gamer’s FPS (first-person-shooter) perspective and the personal narrative recreate the feeling of a place inhabited by both a unique biodiversity and an anxiety for landmines and other invisible dangers.

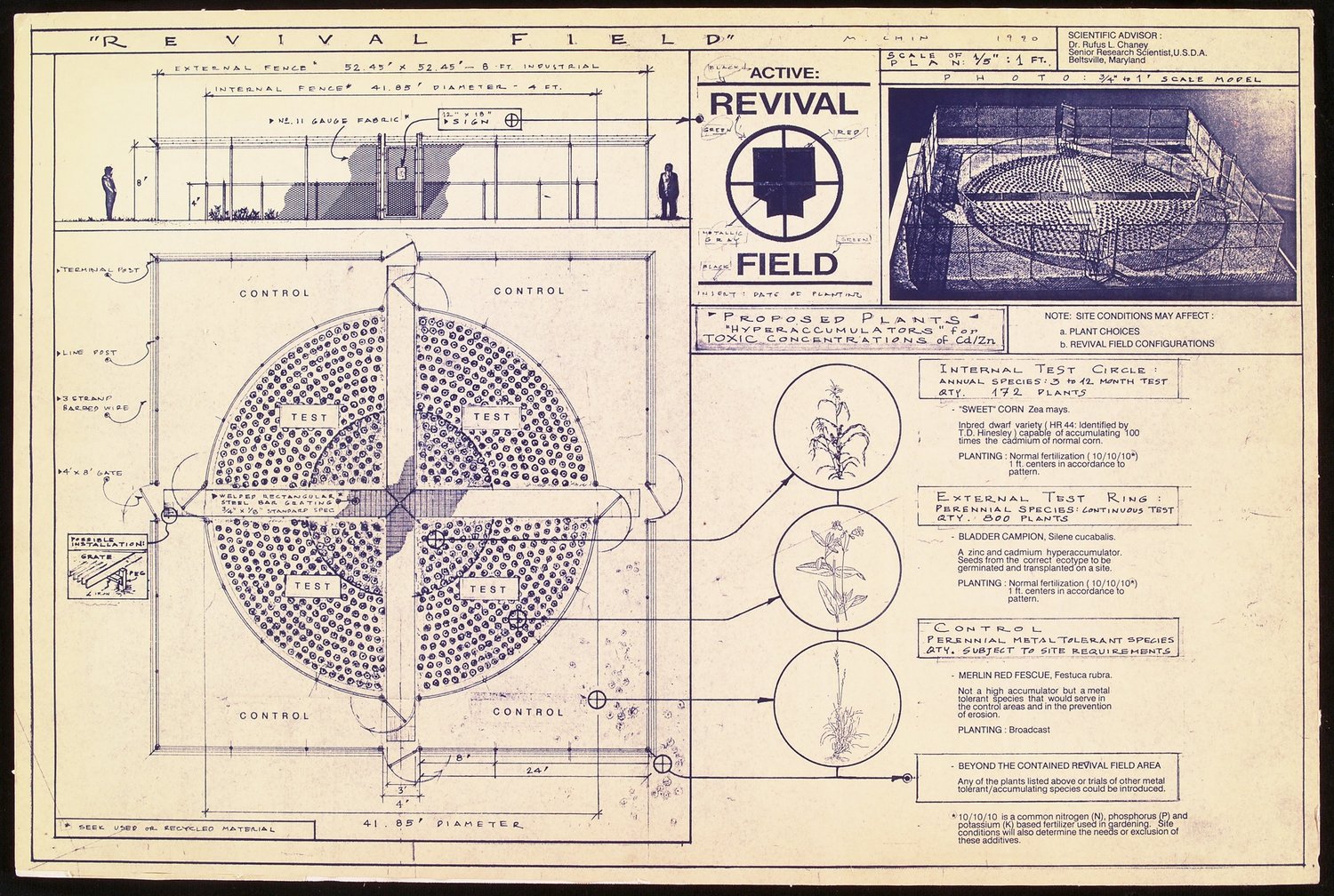

Mel Chin, Revival Field, 1991-ongoing

Mel Chin, blueprint for Revival Field, 1990

Revival Field is a phytoremediation experiment Mel Chin undertook at Superfund site Pig’s Eye Landfill, in St. Paul, Minnesota.

The artist used hyperaccumulator plants as a low-cost means of remediating polluted soil. The species planted on top of the waste tip soak up heavy metal toxins like cadmium, zinc, and nickel from the ground through their roots. When the plants are mature they are harvested, dried and incinerated to recover the metals that is then re-sold to cover the cost of the procedure. Chin collaborated with Dr. Rufus Chaney, a research agronomist who had done pioneering research on the subject in a lab but who had so far never had the opportunity to conduct field research on a contaminated site.

The garden demonstrated that ‘green remediation’ could be a successful low-tech alternative to expensive and ineffective remediation methods to reclaim contaminated soil and toxic waste. It also showed that art can have real, healing effects on the environment.

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, Returning a sound, 2004

Jennifer Allora & Guillermo Calzadilla, Returning a sound, 2004. Photo: Lisson gallery

Vieques is an island off the mainland of Puerto Rico used by the U.S Navy and NATO forces as military testing ground as from the 1940s.

The inhabitants, angry at the expropriation of their land and the environmental and health impacts of weapons testing, organized a campaign of protests and civil disobedience that led to the departure of the U.S. Navy in 2003.

Allora & Calzadilla made a series of works relating to the recent history of this island. One of their videos poetically communicate the interplay between militarism and sound. In Returning A Sound, Homar, an activist, drives around the island on a motorcycle as if reclaiming the territory. The silencer of the vehicle was replaced by a trumpet that echoes the traumatizing sounds of bomb explosions that had shaken the lives of the Vieques inhabitants for decades.

“As artists, we became interested in questions related to the sonic violence that marked this space, as it was exposed to earsplitting detonations up to 250 days out of the year,” explained Guillermo Calzadilla. “The first work we made in that regard was Returning A Sound, which we filmed just after the military lands were semi-opened to the public in 2003.”

Martha Atienza, Our Islands 11°16’58.4_N 123°45’07.0_E, 2017. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

Martha Atienza, Our Islands 11°16’58.4_N 123°45’07.0_E, 2017

Our Islands 11°16’58.4_N 123°45’07.0_E is a quiet and poignant protest against climate change and the decay of local culture in the Philippines. In this subaquatic procession, men wearing all kinds of historical, religious or folkloric costumes advance slowly against the sea and its shifting currents. Leading the parade is a man dressed as the Santo Niño (the child Jesus, Patron of the islands) and carrying a doppelgänger statue. The silent and mesmerizing march replicates Ati-atihan, a celebration that takes place annually on firm ground.

The underwater parade reenacts some of the violent—both natural and political—moments the local communities have been through: the super typhoon Yolanda, the war on drugs, the exodus to find work overseas, etc. The seabed and the corals that surround the performers are unwilling actors that symbolize the assaults to local ecosystems.

Brandon Ballangée, Prelude to the Collapse of the North Atlantic, 2013. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

Collapse is an innocent-looking but nevertheless brutal visualization of one of the tangible consequences of the crises oceans are facing. The specimens kept inside the glass jars pilled up in the shape of a pyramid were bought on a fish market. Some are raw fish and seafood we eat, others were caught by mistake but nevertheless displayed by the fishmongers. These sea creatures represent only a tiny portion of the aquatic organisms that inhabit our oceans. The amazing seabed diversity is being impoverished not only by the plastic pollution that makes the headlines these days but also by oil spills, acidification, overfishing and other environmental degradation. This loss is symbolized by some of the glass jars that remained empty of the extinct species they were meant to contain. How long till more empty jars are added? And what will it take for humanity to react and realize the consequence of this relentless erosion of marine biosystems?

More images from the exhibition:

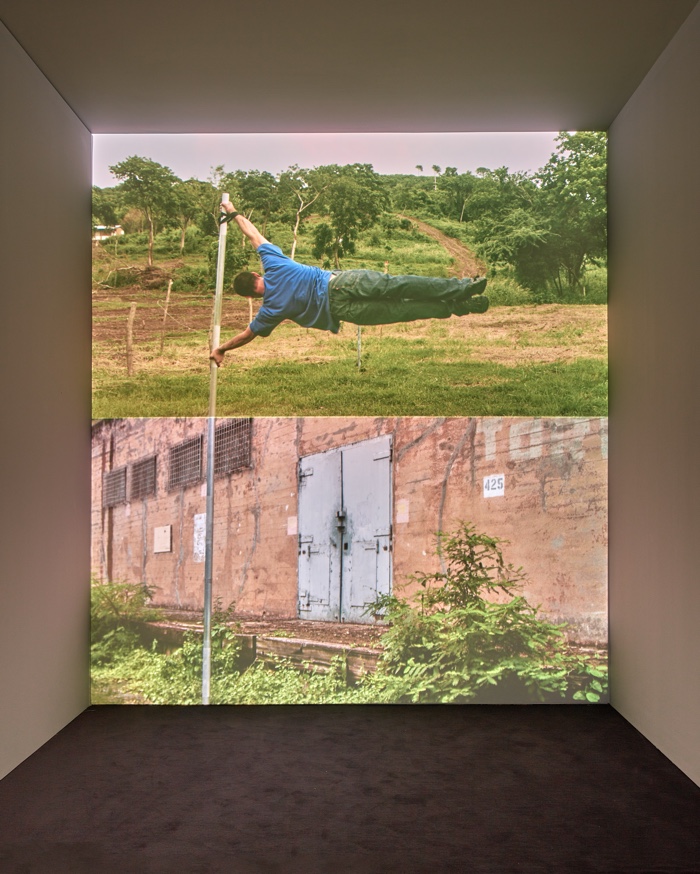

Allora & Calzadilla, Half Mast/Full Mast, 2010. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

Mark Dion, Mobile Bio Type–Jungle, 2002. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

Piero Gilardi, Tronchi Caduti, 1990. View of the exhibition No Man’s Land. Natural Spaces, Testing Fields, Mudam Luxembourg, 2018. © Photo: Rémi Villaggi / Mudam Luxembourg

No Man’s Land was curated by Marie-Noëlle Farcy, Marion Laval-Jeantet and Benoît Mangin. The show remains open until 09/09/2018 at MUDAM in Luxembourg.

If you want to see truly awful photos of the exhibition, check out mine on flickr.

Previously: Arriba! A tropical time capsule in Antarctica and On thrombolites and other victims of human folly.