Marie-Luce Nadal uses discarded materials to create formidable machines that capture clouds, catch lightning strikes and trigger vaporous explosions. Whether they make the sky cry or celebrate the Constellation of Taurus, her performances and sculptures play with atmospheric events and everything that is elusive and ethereal.

Marie-Luce Nadal, Faire Pleurer les Nuages (Make the Clouds Cry), 2015-2022

Nadal learnt to read the clouds from her grandfather, trained as an architect and is now using meteorological variables to explore the human desire to master all natural phenomena and life forms. Equally at ease in scientific laboratories, French vineyards, fencing costumes and artistic workshops, she demonstrates that the intangible can become a material and that practices of geoengineering have long existed in rural areas. Only on a smaller scale and with the objective to protect crops. I had a chance to talk with her a few weeks ago, here’s a transcript of our conversation:

Marie-Luce Nadal, Divinité de la Brume (Deity of the Mist), 2016-2017

Marie-Luce Nadal, Munitions de Foudre (Lightning Ammunitions), 2014-2020

Bonjour Marie-Luce! You trained as an architect and yet, a lot of your work deals with atmosphere, clouds, wind, thunderstorms and other elusive elements. Where did you get this drive to engage with elements that look so uncontrollable, ephemeral and intangible? Surely, this is making your work more difficult!

I hail from a lineage of winemakers, individuals predominantly immersed in matters of roots and the earth.

Nonetheless, in our custodianship of the land and the grapevines, we maintain a steadfast awareness of the skies above us. I recall my grandfather employing a technology to disperse clouds, particularly because hail, before the harvest, remains our most dreaded adversary, and hail, inevitably, descends from the very clouds. During my formative years, I was schooled in the art of deciphering the clouds in this specific region of France. The cloud formations here differ from those in other corners of the world, as you mentioned. As you aptly put it, I pursued a path in architecture. To me, architecture signifies a means of comprehending one’s surroundings more deeply. It imparts the wisdom of both embracing and accommodating the environment while simultaneously providing shelter from it. Architecture serves as a method for creating layers that distance you from your surroundings, thereby fortifying the boundary that separates you from your surroundings.

In many ways, a portion of my work still aligns with this endeavor to intensify that demarcation. I continue to perceive myself as an architect, whether through the fabrication of tools and machinery that enhance the divide between myself and the environment or the creation of objects and cabinets of curiosity that allow me to encapsulate the environment, facilitating my observations and fostering a heightened understanding.

But usually architects deal with mortar, bricks and very tangible materials. Your materials are harder to grasp, they look elusive and difficult to control.

Architecture primarily deals with tangible materials, yet my fascination lies in the intangible substance and how this elusive “substance” can be harmonized to offer a clearer perception of the world. In the role of an architect, I strive to build walls around you for protection but also aim to provide you with the means to envision further and attain a more resilient state. I’m more intrigued by inquiries into existence rather than material concerns.

Concerning my profound connection to the soil, which has been ingrained since my childhood, I’ve always been taught that what we create doesn’t truly belong to us. Despite being told that we own the land, everything surrounding us is merely lent to us. Our duty is to return it, if not in its original state, then in an improved condition from when it was first entrusted to us. Everything is borrowed. What captivates me in this lending process—whether it involves tangible materials or intangible energy—is that which is most fleeting, ethereal and transient. The wind is the wellspring of all my work, as are the clouds, these ethereal forms in perpetual rebirth. I’m also intrigued by the energy harbored within the wind, the clouds, and beyond. It’s this energy that holds my fascination, whether it manifests as thunder or the “coups de foudre,” which elude precise translation into English but I would interpret as the emotions that reside within us.

Marie-Luce Nadal, Faire Pleurer les Nuages (Make the Clouds Cry) (film still), 2015-2022

Faire pleurer les nuages/Make the Clouds Cry is visually very striking. However, there is something very violent in this idea of shooting towards the sky. Is this a metaphor for humanity’s ambition to tame nature and the brutality that goes with it?

Is it possible to domesticate nature while respecting it? To work with it, instead of against it?

The performance Make the Clouds Cry carries on the legacy of my grandfather and great-grandfather, who practiced cloud seeding to prevent hail and safeguard their harvests. Cloud seeding, a 20th-century technology, allows for the alteration of cloud behavior to avert hailstorms. My grandfather employed this technique to combat hail. “Make the Clouds Cry” represents a distinct quest, where I seek to encourage the sky to communicate its emotions through a unique blend of handmade fireworks and my Madeleine crossbow.

Does it work? I looked for scientific articles. I couldn’t find any consensus about the effectiveness of the technique.

The technology involved is rather straightforward. Clouds are composed of water, air and a touch of dust – these minuscule dust particles, or aerosols, are what I gather. Interestingly, these very same aerosols are dispersed when discussing cloud seeding.

This method hinges on harnessing these minute airborne imperfections. Without them, it would be virtually impossible to create those tiny ice droplets that, when combined with countless others, give rise to a complete cloud formation. The core principle of cloud seeding revolves around selecting a specific type of these imperfections. Multiple types exist, but the one I’m most familiar with is silver iodide, which is also employed in photographic processes. What sets silver iodide apart is its ability to freeze at relatively higher temperatures.

What captivates me is the technique my grandfather employed back in the day: launching rockets into the sky. In contemporary times, the method used by farmers in France employs a network of unobtrusive small chimneys that can be discreetly installed in your neighbor’s garden. Their effectiveness relies on a chain of faith and trust in your neighbor’s actions. The wind carries the particles released above your garden to your neighbor’s, which means having one of these devices doesn’t protect you; rather, it safeguards your neighbor from hail. The hope is that your other neighbor will reciprocate.

The efficacy of this system isn’t easily quantifiable because it operates on trust and is nearly imperceptible. However, it appears to be highly effective.

Is the effect immediate?

The timing of deploying this endeavor into the skies is crucial. It demands an extensive knowledge of meteorology. Over the many years I’ve resided in this particular region, I’ve developed an ability to discern those clouds indicative of impending hailstorms. A skilled and seasoned observer can anticipate their arrival. Nevertheless, it remains uncertain whether I could readily identify a hail-bearing cloud in a foreign landscape. The ancient craft of cloud interpretation is a tradition passed down through the generations.

In France, the overarching system is overseen by a national organization. Consequently, this very organization is responsible for conducting all environmental assessments related to this technology, making it a challenge to attain an unbiased evaluation. Undeniably, this technology carries repercussions that disrupt the natural order.

To offer a more comprehensive response to your question, it’s imperative to return to my roots, to the place where my journey began. Everything I undertake is intrinsically linked to my profound connection with the soil, and more significantly, to the wisdom imparted by my grandfather, who was a stalwart soldier throughout his entire life, having served in World War I, World War II and the Algerian War. Weapons were an ever-present part of his life; conversations about warfare were commonplace during my formative years. I was raised with the idea that we must contend with nature to achieve our ambitions.

My curiosity lies in exploring the delicate boundary between art and science, and the equally subtle distinction between science and fiction. The quest to domesticate nature walks a fine line between collaboration and subjugation. I find great satisfaction in navigating this boundary and discerning when we may lean more toward one side than the other.

With “Make the Clouds Cry,” I continue the legacy my grandfather initiated. While it was his vocation, for me, it has evolved into a performance that enables me to contemplate forces far grander than ourselves. It raises a fundamental question: why do we strive to control that which eludes our grasp? My connection with warfare has shed light on the fact that the desire for control often stems from a fear of loss. Make the Clouds Cry embodies not only an aspiration for control but also a pursuit to perceive the emotional essence residing within the clouds, rather than assert ownership over them.

Marie-Luce Nadal, The Factory of the Vaporous No.2, 2017

Marie-Luce Nadal, The Factory of the Vaporous No.1, 2015

You made several machines called “Factory of the Vaporous”. How do they differ from each other?

I started working on my very first machine while I was studying architecture. The idea behind it was to capture the imperfections that, in my eyes, give the sky its unique character. Initially, I envisioned a machine designed to cover an entire city, allowing for large-scale harvesting. However, I faced funding challenges, which led me to downsize the concept, making it the size of a piece of furniture and later expanding it to the dimensions of a yurt. It wasn’t until I met Rebecca Lamarche Vadel, who proposed my first solo exhibition at the Palais de Tokyo, that the machine found its definitive form, measuring 1 meter by 1.30 meters.

The production of each machine and the tools it employs always adapt to the specific context. The Factory of the Vaporous No.1 was created using recycled materials from a recently closed alcohol distillery near my parents’ home. It’s a compact machine constructed on pallets for easy transport. Its motors and small ventilating robots produce a sound akin to that of a fan. In contrast, the second machine is more substantial, resembling a totem, standing at 3.50 meters in height and emitting a sound reminiscent of a farm tractor. I had the opportunity to build this larger machine during an invitation to Russia in 2017, utilizing components recycled from an old car wreck.

I’m hopeful that in the near future, I can develop a new model that’s compact enough to fit inside a suitcase. This is because I find myself traveling extensively, and I would like the harvesting process to be more portable and accessible.

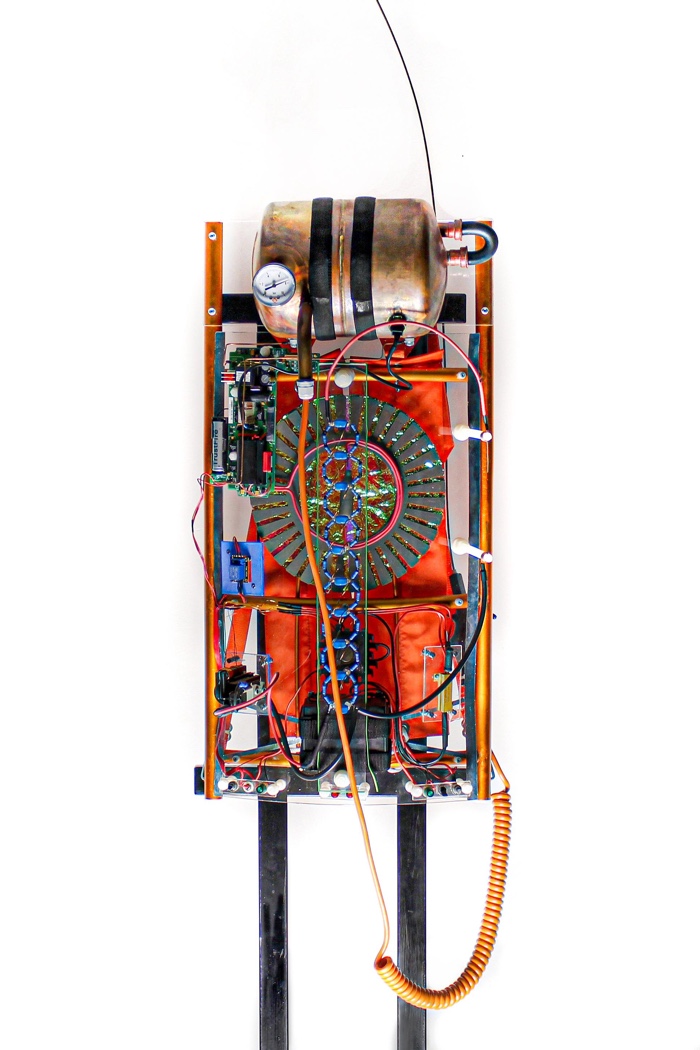

Marie-Luce Nadal, Portable Lightning Extractor, 2018

Marie-Luce Nadal, Portable Lightning Extractor, 2018

I am very puzzled by the Portable Lightning Extractor. This is probably due to ignorance but the idea of collecting lightning extracts looks both poetical and whimsical but not realistic. How does it work? Does it work?

Is this claim accurate, or could it be a fabrication? Once more, we find ourselves standing on the threshold between fact and falsehood. What, indeed, constitutes the essence of truth? Is truth solely ascribed to the domain of science and the phenomena unveiled by scientific instrumentation? Can fiction be a semblance of truth or its antithesis? Navigating the complexities of truth in our contemporary age is an arduous task. I believe that in the present day, there’s a growing need for a closer alignment between science and faith.

The Portable Lightning Extractor is a wearable backpack designed for individuals who have undergone some basic training. To operate it, you must carry a positive charge, as it’s the voltage contrast between you and your environment that generates the spark. This process is akin to the phenomenon of “coup de foudre,” a term borrowed from the French language, which typically signifies a profound and instantaneous romantic attraction. This concept draws inspiration from the fundamental principles of nature, where chaos tends to naturally revert to a state of equilibrium. It underscores the idea that from an initial imbalance, a new balance emerges.

In the atmosphere, there exist ions and electrons, which naturally create a voltage disparity. When this voltage difference becomes sufficiently potent, it can trigger an electric shock, serving as a mechanism to restore equilibrium, much like a glass breaking to release its contents. This understanding predates modern Western science, with historical roots dating back to the Middle Ages.

During that era, people believed that love emanated from the heart, viewing the heart as a pump that circulated our blood. According to this perspective, love originated within the heart and was subsequently pumped, much like blood, towards the eyes. This journey of love extended from one person’s eye to another through the medium of eye sweat. As this transferred “love” reached the other person’s eye, it caused an additional surge of blood, thus feeding them with affection. This romantic notion gave rise to the expression “love at first sight.”

The concept of “coup de foudre” emerged during the Renaissance, as people of that time recognized the substantial voltage difference between individuals and the need to restore balance. This viewpoint was their interpretation of love. In the following centuries, people drew parallels between this understanding of love and the way lightning operates.

Returning to the backpack, it features a fencing handle that extends into a lengthy metallic rod, which you employ to metaphorically “whip” the sky, akin to fly fishing.

Marie-Luce Nadal, Munitions de Foudre (Lightning Ammunitions), 2014-2020

That sounds scary.

To use it?

Yes, I’d be scared.

Maybe that’s exactly why you should try it.

I only capture lightning when the weather is clear or favorable.

Learning to capture that little spark is a skill of its own. Sometimes, when you’re out hunting for lightning, you might return empty-handed. But on better days, you catch that spark. If it’s strong enough, it charges up your backpack.

Now, here’s the interesting part. You’ve got a small tester that shows at least 30,000 volts, and this is what you need to charge a special type of ammo. This ammo is basically a gas cartridge that’s been filled with gas beforehand. When you hit it with 30,000 volts or more, something interesting happens – the gases inside get transformed and oxidized in a unique way each time. What comes out of it is always a bit different.

These modified cartridges, which have now become your thunderbolt ammo, can be used again. Each one is unique and has a unique range.

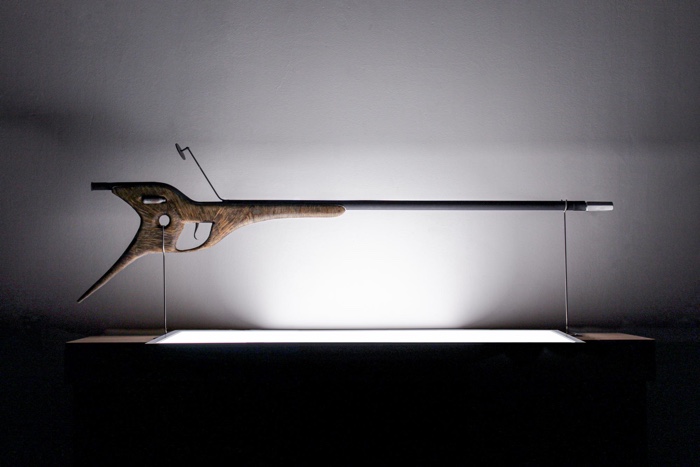

The tool you use for this is called an Aura Fulminis 21, which is like a rifle with a 21-diameter barrel. It’s made from wood, steel, and brass wire, and it has a viewfinder that acts like a mirror. You place the rifle stock right in front of your mouth, and when you see your own eyes and mouth in the viewfinder, it means your target is right in front of you. You shoot, and the cartridge at the end of the barrel opens, sending a blast into your mouth.

This whole process gives you a kind of electric high because you’re essentially inhaling the air trapped inside the cartridge. It can make you laugh for a few minutes or send you into hours of vivid dreams or deep sleep. Each experience is a bit different, just like catching lightning itself.

Marie-Luce Nadal, Aura Fulminis 21, 2017

Marie-Luce Nadal, Aura Fulminis 21 (detail), 2017

I saw a mention of a recent project of yours called S.O.S (The Skin Of the Sky). The text said that the work attempts to find a protective armour for the planet, based on the study of lightning and thunderstorms, which have now become increasingly common. Can you tell us about the background of the project and what you are trying to achieve with it?

S.O.S. serves as a valuable tool for navigating in a perpetually changing world. While the projects I’ve discussed thus far have primarily focused on local scales, Skin Of the Skin operates on a global level. It functions as both a means of exploring our atmosphere and an opportunity to transform our relationship with the environment. S.O.S. is designed to be a near-real-time lightning and atmospheric map, presented in the form of a sound performance and wearable objects for interactive engagement.

As you may be aware, lightning strike incidents are on the rise due to climate change. It’s crucial to document these changes, and I aspire to do so with a unique form of mapping. The word “map” originates from “mappa mundi,” meaning a sheet of the world that envelops us. I envision this covering to be a protective shield for both our planet and ourselves. Furthermore, I aim for this map to help us navigate through the intricacies of our atmosphere.

In collaboration with a scientist from JPL in Pasadena, Los Angeles, we’ve developed a real-time data retrieval device. Our next step involves making this data not only visible but also experiential. This is a multifaceted, long-term project. The initial phase will comprise a sound installation, a collaborative effort with a remarkable U.S. sound artist. We plan to create a map every 12 hours, condensed into a one-hour concert experience. In this immersive concert, natural phenomena such as lightning, rain, the absence of rain, and cloud cover will serve as sound parameters, enveloping the audience in a site-specific auditory map.

Is the performance taking place outside or inside a gallery and is it influenced by the weather?

The sound installation depends on the weather. The artist I work with will generate a series of sounds that respond to five climate parameters. Once the bank of sound data has been created, the atmosphere, climate, weather will generate a unique partition. To say it an other way, we design instruments and harmonies for interpreters that are atmospherical events.

Can particular climate conditions render the performance particularly difficult, interesting or else a bit less lively?

Certain weather conditions can make our performance more exciting, especially in places where lightning is common. However, I’m also hoping for some unexpected surprises along the way.

Now, as for the sounds of lightning strikes, I’m working on a free app that allows people to express their wishes and intentions. The main purpose of this app is to help users keep track of their goals and express them more clearly. We’re going to collect these intentions, whether they’re personal or for someone else or even for the world. These whispered wishes will be shared on the S.O.S. platform, where they’ll be connected to lightning events. During each performance, when lightning lights up the sky, you’ll hear these whispers of human wishes filling the air. That’s why working in places with frequent lightning is going to be quite thrilling for us.

How did you get to work with that U.S. scientist?

Collecting Coups de foudre by myself has been somewhat exhausting, so I decided to take a step back and gain a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. I’m also deeply intrigued by the ideas and projects of Bruno Latour and Frédérique Aït-Touati. I’m particularly fascinated by all the inquiries related to reshaping maps.

Any upcoming projects, field of research or event you would like to share with us?

S.O.S. marks the beginning of a new chapter for me. While the initial phase centered on domestication, I am now exploring ways to coexist harmoniously with both ourselves and our planet. This exploration has kindled my interest in the astronaut as a symbol and the evolution of their representation, dating back to the iconic image of Earth from Space. The depiction of this heroic figure amidst the cosmos harkens back to historical representations of figures such as the Virgin Mary, Kings, and even deities.

Furthermore, I’m concurrently working on a series of sculptures that will feature diverse elements, including a diving board for those unburdened by interstellar vertigo and gardening tools suited for a gravity-bound environment. These tools ultimately serve the purpose of helping us not only to explore space but also to inhabit and nurture our own planet.

Merci Marie-Luce!

Previously: Weather Engines. The poetics, politics and technologies of the environment, Who owns the clouds and the water they contain?, Man Made Clouds: atomic, phantasmagoric and political, Strange Weather: into the clouds, Cloudscapes by Transsolar + Tetsuo Kondo, etc.