If you speak French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, you know that they are sexist languages. I mention these 4 languages because I’m quite familiar with them but I suspect that the same goes for other languages that have different genders. In Italian, an unmarried woman is a zitella, an unmarried man is a scapolo. The zitella is pictured as a faded and pitiful woman. The scapolo is free, content and has the world in front of him. A few weeks ago, the new edition of Treccani, Italy’s historic dictionary, made a small revolution in the world of linguistics and beyond by registering the feminine form of nouns and adjectives on an equal footing with the masculine as well as abolishing gender stereotypes. Before that, the masculine form of a word always appeared before the feminine form even when, if you follow the alphabetical order typical of any dictionary, the feminine form should have been first. An easy example would be that, until a few weeks ago, bello always appeared before bella in the dictionary.

Roberte Larousse performance for the group show Continuer Sans Accepter, 2022. Photo: Luce Moreau for Lab GAMERZ

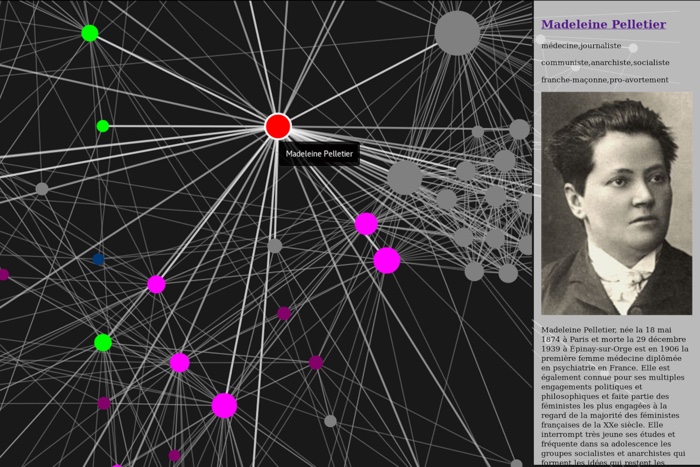

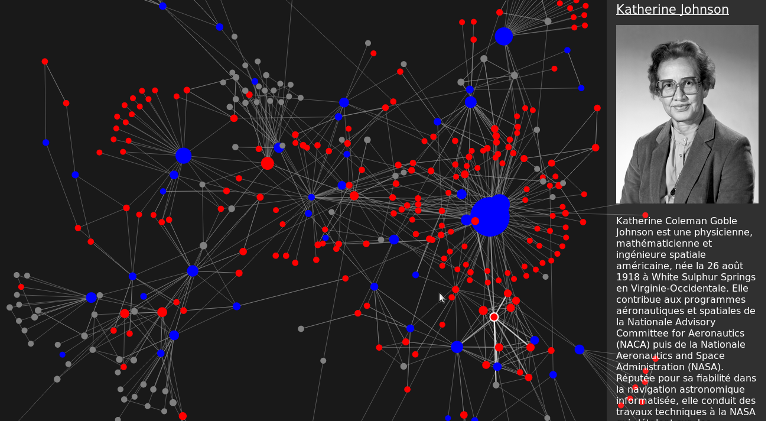

Roberte Larousse, Wikifémia. Visualisation of the network around article Madeleine Pelletier in French Wikipédia

And what about French, my mother tongue? I love French but it has a bit of an MCP aura. At school, I learnt rules that literally said “the masculine form takes precedence over the feminine form”. There are many debates (the French love to debate about French) about the feminisation of the language but it is a slow and relentless fight. Fortunately, Roberte la Rousse has entered the arena. Roberte la Rousse – aka Cécile Babiole and Anne Laforêt – takes her name from the two most famous dictionaries of the French language: the Petit Larousse and the Petit Robert. Laforêt and Babiole feminised and brought the two competing dictionaries under one name to better dispute the binarity and machismo of the French language.

Roberte la Rousse’s sharp, feminist and playful performances invite the public to ponder upon the necessary “demasculinization” of language and knowledge. The Wikifémia Révisions performance, for example, proposes to review and update our knowledge of women who have shaped our understanding of gender but also to rectify that knowledge by pointing out biases in Wikipedia articles and making the necessary corrections or additions. Roberte LaRousse selected women belonging to different times in history, currents of thought and practices: Françoise d’Eaubonne, Annie Sprinkle, Monique Wittig, Nnedi Okorafor, Ni una menos, George Sand, Virginia Woolf, the Guerrilla Girls, etc.

Roberte la Rousse recently performed Wikifémia – Révisions at Continuing without accepting, a collective exhibition curated by Lab GAMERZ at Chapelle Venel in Aix-en-Provence. The tile of the show alludes to the cookies popping-up on our screens every day to give us an illusion of autonomy and privacy in a technological universe where we are both target and product. The artworks in the show manipulate languages to push against the commodification of internet activities and experiment with strategies to reconnect with the promises of the early days of the internet: emancipation, experimentation, sharing of knowledge and know-how.

Roberte Larousse performance for the group show Continuer Sans Accepter, 2022. Photo: Luce Moreau for Lab GAMERZ

Roberte Larousse performance for the group show Continuer Sans Accepter, 2022. Photo: Luce Moreau for Lab GAMERZ

I didn’t get to see the show, alas! but I did get to interview the artists. Roberte la Rousse systematically speaks FrançaiSE, that is to say entirely à la féminine. I translated our conversation in a way that will hopefully reflect their observations and approach:

Bonjour Roberte la Rousse! When I emailed you to ask for an interview, I was full of enthusiasm. A moment later, I remembered that my blog is in English, a language that is mostly non-gendered and I realised it would be tricky to convey precisely what Roberte la Rousse does. How would you describe your work to an audience whose main language doesn’t embody such a deep layer of sexism?

In French, just like in other Latin languages, gender is omnipresent since all common nouns have a gender (the sun, the armchair are masculine, the moon, the chair are feminine…) which extends to determiners, adjectives, pronouns, past participles with which they agree. Besides, the neutral takes the form of the masculine in French. Thus the masculine imposes itself, against all logic, in expressions such as: Quelle heure est-il? (What time is “he”?) instead of: Quelle heure est-elle? (What time is “she”?) which would be the expected form since the word heure (hour) is feminine. Finally, the Académie Française established, in the 17th Century, the primacy of the masculine over the feminine: “the masculine always prevails over the feminine”, on the pretext that “the masculine gender being the most noble, it must predominate when masculine and feminine are found together” wrote the academician Vaugelas in 1647. Here is an example given by Michèle Causse (one of the most virulent writers against the kidnapping of the language by men): une femme et trois cochons sont entrés (masculine plural) dans la pièce (a woman and three pigs entered in room), dix femmes et un cochon sont entrés (masculine plural) dans la pièce (ten women and a pig entered the room.) The names of noble professions only exist in the masculine, for example philosophe, médecin (philosopher, doctor)… And in general, the feminine is pejorative, a sign of a deep misogyny of the French language. Thus, un professionnel (masculine form of a professional) is someone who knows his job well, une professionnelle (feminine form of a professional) is a prostitute; un couturier (masculine) is a fashion designer, une couturière (feminine) is a seamstress; un sorcier is a magician, une sorcière is a witch, an ugly and mean old woman…

In order to counter this sexism deeply enshrined in the French language, Roberte la Rousse decided to express herself in a language that eliminates all masculine form, by systematically replacing them with feminine forms. Our goal is not so much to feminize the language as to abolish gender altogether. Thus, in the language of Roberte la Rousse, there are not two or three genders but only one which takes the grammatical form of the feminine, since you have to choose a form. We called this language la française (feminine French).

Anne Laforet is a researcher and Cécile Babiole is a visual artist. What made you decide to ally and work on the theme of language, gender and technology?

We founded the Roberte la Rousse collective in 2016, but we have known each other since the early 2000s, our friendship was born from a common interest in arts and technology. It was the era of net art (Anne Laforet wrote her thesis on the subject) and the beginning of real-time signal processing software (that Cécile Babiole used in her installations and performances). For the past ten years, language has been a recurring theme in Cécile Babiole’s artistic work (Spell, Word Distributor or Vocabulary Lesson and many other pieces.) while Anne Laforet is interested in gender issues (she was an active member of the Parisian feminist queer hackerspace Reset from 2018 to 2020). And it is quite naturally that we decided to work together by crossing our favourite themes: language, gender, technology.

I’m curious about the technological aspect of your work. What roles does technology play in language today? How does it affect the masculinisation (or de-masculinisation) of a language like french?

The masculinisation of the French language took place at two key moments in history. First, in the 17th century, with the sexist rules enacted by the Académie Française and more recently from the 2000s onwards with the massive use of artificial intelligence in the automatic processing of language which leads to systematisation of sexist biases in the language.

Indeed, AI algorithms learn from big data, that is to say from considerable quantities of linguistic samples taken both from Wikipedia and from posts on social networks. These technologies are not based on grammar rules laid down a priori but on usage which means that they convey, transmit and reinforce stereotypes coming from the Internet. This phenomenon is obvious with the digital tools used daily on the Internet, such as search engines or automatic translation software, which systematically favour the masculine to the detriment of the feminine and men to the detriment of women. Thus, on Google Translate, la cheffe d’orchestre (female form of “the conductor”) is translated into Spanish by el conductor, that is to say the male conductor, and the nurse by la enfermera, that is to say the female nurse, passing on the prevailing social stereotypes.

Roberte Larousse, Wikifémia. Visualisation of the network around article Katherine Johnson in French Wikipédia

If I understood correctly, you wrote an algorithm that replaces masculine words with words in feminine form. Did working with the algorithm reveal something about the French language that you didn’t expect?

In our texts, the radical elimination of any mark of the masculine highlights, on the contrary, how much the French language is masculinised.

In order to preserve the intelligibility of la française (feminine form of le français, the French language), we have devised a very simple general rule of demasculinisation. It consists in systematically replacing the masculine form of a word with the feminine form existing in current French, whatever they are grammatically or semantically. We say la livre (instead of le livre, the book), une texte (instead of un texte, a text), une homme (instead of un homme, a man), pas de la toute (instead of pas du tout, not at all)… We have added the present and past participles: we walk en chantante (instead of en chantant, we walk singing) or a votée (instead of a voté, voted.) The result sounds a little weird. But it is precisely this oddity that interests us. Our automatic translation script sometimes leads to literary finds or funny turns of phrase that we wouldn’t have thought of otherwise: la boulotte (which translates into “the dumpy one”) instead of le boulot (the job) or la fine (the slim one) instead of la fin (the end), the sentence vous n’aurez pas le culot d’élire un homme à nouveau (“you won’t have the nerve to elect a man again”) becomes vous n’aurez pas la culotte d’élire une homme à nouvelle (“you won’t have the panties to elect a man of short stories!”)

In Wikifémia – Révisions, you read Wikipedia entries of women or feminist collectives that you comment, correct and review. Do you also intervene directly inside the wikipedia platform? How different are Wikifémia – Révisions from the Wikipedia Edit-a-thons where people meet for several hours or days to edit or complete wikipedia and increase the presence of women scientists, activists or artists in the platform?

Wikifémia is an artistic project that proposes a re-reading of Wikipedia from a feminist perspective. We create stories based on articles found in the French version of Wikipedia devoted to women or groups of women. We select excerpts from articles that we arrange, comment on and translate into la française. Wikifémia is an independent project of Wikipedia.

In addition, we participated in many Edit-a-thons organised by les sans pagEs (an association of French-speaking Wikipedians who work to bridge the gender gap in the encyclopaedia) during which we learnt to contribute but above all discovered the behind-the-scenes of Wikipedia. We were able to observe the many biases present in the encyclopaedia (biases of gender but also of race or class) and this fed our artistic project.

With Wikifémia, we were interested in different themes: the place of women in computer science, activists for universal suffrage and reproductive rights, and personalities who influenced us (writers, artists, activists.) We have actively contributed to Wikipedia on these topics.

What kind of feedback do you get from the audience? French speakers tend to have a possessive and ultra-conservative relationship with their language. They don’t like it to be simplified, they don’t like discussions to make it more inclusive, etc. How do they react to your work? Do men experience it differently than women for example?

And has the feedback you have received from the public ever influenced your practice with Roberte la Rousse?

The public of our performance seems to appreciate our texts in “française” and the touches of humour that pop up here and there. But it is true that some spectators, mostly men, can be irritated by our approach, they are the same ones who refuse any spelling reform or any borrowing from the other languages spoken in France and defend the conservative conception of a “pure” and frozen language.

A recurring question comes up when we discuss with the audience, that of comparing la française with inclusive language, that is to say a language that tries not to exclude anyone (for example, instead of a generic masculine tous (all) the inclusive language says tous et toutes or toustes or tou⋅tes with a midpoint). This question from the public allows us to take stock of our practice. La française and inclusive language are not to be placed on the same level. We are not trying to impose a new linguistic standard on French speakers, we want to offer an artistic, that is to say symbolic, work on the language.

The consequence of our choice is to bring out the massive masculinisation of patriarchal French and create a strange language with poetic accents (probably difficult to perceive for non-French speakers). In contrast, in life, we welcome all forms of inclusive language.

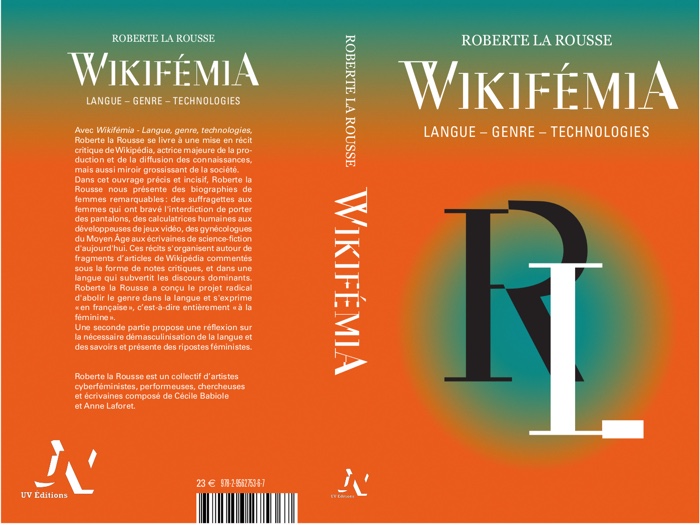

Wikifémia – langue, genre, technologies, UV éditions, 2022

Roberte la Rousse recently published Wikifémia – langue, genre, technologies (Publisher: UV éditions), a book that not only presents (and comments on) the biographies of remarkable women but also argues that a de-masculinisation of both language and knowledge is necessary. Why is this de-masculinisation so important? How does a language with a heavy patriarchal burden affect women and society in general?

The thesis underlying our thinking is that language is not neutral, words are not transparent labels. On the contrary, language is an ideological construction shaped by the dominant groups, it conveys values which shape reality and are imposed on all speakers. When children are born and learn to speak, the language is already there, it is not only a communication tool, but an environment in which they are immersed and which builds the world without their knowledge.

However, it is clear that women are mistreated in French, a language that conveys a consistent contempt for women and the feminine. It is therefore essential to work on language since it conditions thought and the vision of the world and of society. Under these conditions, proposing a demasculinisation of the language, which “sabotages” the dominant discourse, constitutes a tool for raising awareness and for fighting against patriarchy.

In terms of knowledge, Wikipedia is one of the most visited websites in the world, just after Google and Facebook. Its significance as a distributor and producer of knowledge is thus considerable. This is why it is important to scrutinise its biases, but also to question its pseudo-neutrality. The knowledge produced by minoritised communities (women, racialised people, the Global South, gender dissidents, etc.) is under-represented. This is what inspired us to write Wikifemia.

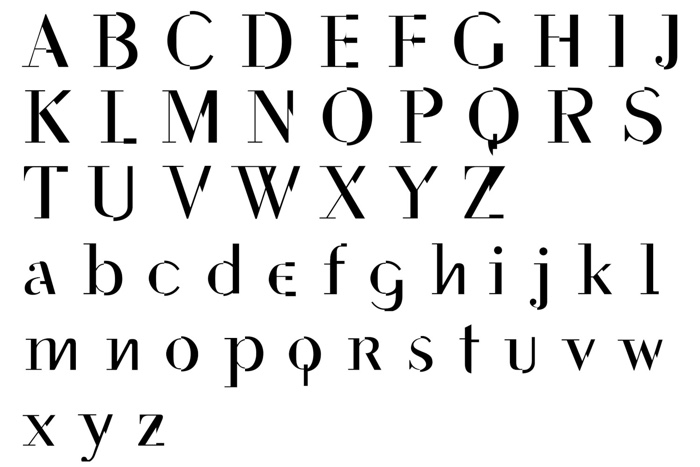

Cécile Babiole, La Berte typography, 2021

The work of Roberte la Rousse is about language, gender and algorithms but it also has a strong visual dimension. Can you describe the aesthetic elements of RLR? The way you use colours (you wear pink during the performances for example), fonts or the info visualisation you use in the Wikifémia- Madeleine Pelletier performances?

The visual identity of Roberte la Rousse is developed by Cécile Babiole who created the collective’s logo (printed on the T-shirts worn by the artists during the performances) as well as an original typeface, La Berte, used for the titles of the book Wikifémia, langue, genre, technologie (UV editions, April 2022).

La Berte consists of a composition of two emblematic typographies used by the two dictionaries Le Petit Larousse illustré and Le Petit Robert. The graphic principle adopted is to cut out the glyphs by making the assembly visible.

To highlight our working protocol during the Wikifémia – Madeleine Pelletier and Wikifémia – Computer Grrrls performances, we have developed interactive maps that make visible the links between Wikipedia articles dedicated to women.

What is next for RLR? Any upcoming project, event or field of research you could share with us?

We continue to present Wikifemia, and we are thinking about our next project.

Merci, thank you Anne and Cécile!

Roberte la Rousse recently performed for the collective exhibition Continuer sans accepter, organised by Lab GAMERZ in the context of A 5th Season – Aix-en-Provence Art and Culture Biennial