We have dammed, diverted and managed water resources for centuries and yet many regions in the world are still trying to increase access to water supplies. With severe droughts, increasingly erratic rainfall and other worrisome weather events expected to become the norm in the future, some worry that techniques and technologies that intentionally affect atmospheric forces will become more common. With farmers calling for cloud-seeding to water crops, is weather modification (aka “precipitation enhancement”) the ultimate solution for dealing with an increasingly unsettled water cycle? Could clouds become a commodity in the coming decades? Will richer nations disrupt other countries rainfall patterns in other to monopolise precipitations? Will they fight over clouds and the water they contain? Who has the right to control the atmosphere?

A boater gets an up-close view of the “bathtub ring” on the Lake Mead reservoir— evidence of its low water level — while touring Hoover Dam. Photo: Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times

These questions and many more emerged in discussions that followed Maxime Berthou‘s presentation at the Metaboles art event in Marseille, France, a few weeks ago. The artist wasn’t trying to solve the most pressing agricultural or air-cleaning problems. His investigation looked at the implications of cloud-seeding as an artistic gesture.

Cloud seeding, a technology designed in the 1940s, involves infusing clouds with particles of -usually- silver iodide to turn lightweight water droplets into heavy droplets of rain or snow. A more recent techniques consists in zapping clouds with an electric charge. But what matters for Berthou is not the technique, it is the fact that, at the moment, cloud moisture does not have a clearly defined status. It is suggested that international law should elaborate a jurisdictional regime that takes into account both the particular nature of clouds and the implications of new technologies.

Maxime Berthou (aka Monsieur Moo), Paparuda (still from the film), 2011

Maxime Berthou (aka Monsieur Moo), Paparuda (still from the film), 2011

During Métaboles, the artist showed us extracts from Paparuda. The video documents a public performance in which he artificially provoked artificial rain.

Paparuda is a deity from the Romanian mythology, probably pre-Roman. It was invoked by groups of women during periods of drought in the hope that the deity would trigger the rain. By giving this name to the performance, the artist intertwines ancient rituals of rain dance and current forms of geo-engineering, fantasy and scientific manipulation of atmospheric rhythms.

Maxime Berthou (aka Monsieur Moo), Paparuda, 2011

Maxime Berthou at Metaboles. Photo: Luce Moreau

The performance took place above a boreal forest on the border between Canada and the United States. Using weather balloons ordinary used to study climate, the artist launched 15 kg of silver iodide in the Canadian sky to seed clouds going in the direction of the United States. The seeding basically meant that Berthou attempted to “steal” clouds heading to the US and make them rain over Canada. This artistic gesture hinted at the possibility of geopolitical disputes arising between neighbour countries over the ownership of clouds.

Before embarking on the project, the artist tried to obtain a licence to climate change under the mandate of the treaty RQC-P43, r1 from the Ministry of the Environment in Canada. This decree legislates the provocations of artificial rain in North America. It had never been solicited before which means that the request puzzled the relevant authorities in Canada. Berthou decided to carry on with the performance anyway, clandestinely and with the support of scientists.

It took 3 years and a number of collaborations with lawyers and research centres before the artist managed to achieve the performance. The result of the artistic gesture, rain, might look mundane and insignificant to us. However, if we pause to think about the recent floods in Western Europe or the ongoing drought and fires across the planet, it’s hard not to speculate on how cloud-seeding might shape geopolitics in the future.

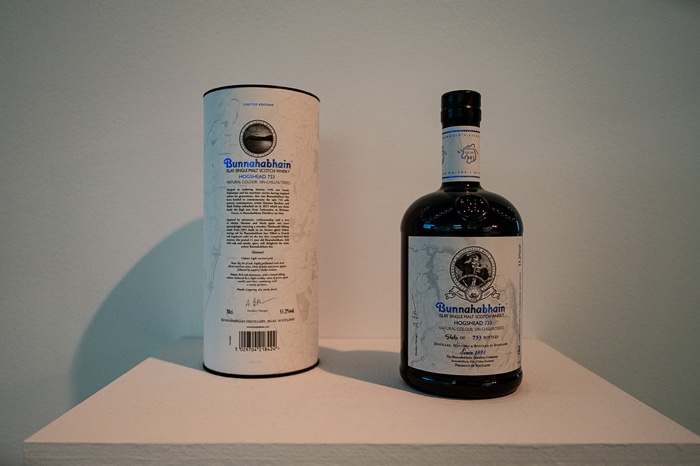

Maxime Berthou and Mark Pozlep, Hogshead 733, 2015-2020

Maxime Berthou and Mark Pozlep, Hogshead 733, 2015-2020

Maxime Berthou and Mark Pozlep, Hogshead 733, 2015-2020

Maxime Berthou and Mark Pozlep, Hogshead 733, 2015-2020

Maxime Berthou and Mark Pozlep, Hogshead 733, 2015-2020

In 2015, Berthou confronted even more rain for another performance. Together with Mark Požlep, he sailed a 1941 wooden fishing boat on her last 733-mile (1179,65 km) journey. It took the artists 4 weeks and 20 stops along the way to sail from from Trébeurden in Brittany to Islay, an island on the ‘whisky coast’ of west Scotland. Once arrived at their final destination, they cut the boat’s hull and used the wood to make whisky barrels. The casks were then used to finish Bunnahabhain’s peated Moine single malt whisky that had been maturing since 2003. 733 bottles were released for sale.

Every stage of the adventure offered the artists an opportunity to explore the poetics of a specific practice of traditional manual labour: restoring a wooden boat, braving the elements on a small vessel, dismantling a boat, crafting barrels (that’s called coopering), producing whisky, etc.

Maxime Berthou‘s moonshine tasting evening at Metaboles. Photo: Luce Moreau

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Maxime Berthou & Mark Pozlep, Southwind, 2019–ongoing

Berthou and Pozlep’s next navigational adventures saw them sail the Mississippi River on a 6-meter restored steam-powered paddle boat.

The trip started on 2 September 2019, one month after the upper Mississippi had been hit by six months of flooding. Many of the cities along the river had been washed away, marinas had been devastated and the infrastructure along the river abandoned. Local populations were struggling with the economic, environmental and sanitary consequences of the floods.

It took the duo almost 2 months to cruise the Mississippi River from its source in Minnesota to its mouth in Louisiana. The trip was punctuated by stops imposed by the limited capacity of the boiler. “We needed a lot of wood,” Pozlep told a journalist. “For one day of travel with the steam, one third of the boat was full of wood.”

These wood cutting breaks were the pretext to meet local farmers and collect corn produced in each state crossed by the river. The artists gathered around two tons of corn, 42 varieties in all. The cereals were then sent to a distillery in New Orleans to produce Moonshine, the illicit liquor of the prohibition. At the end of his presentation at Metaboles, Berthou invited the public to a moonshine-tasting session of the alcohol produced in New Orleans.

Just like Hogshead 733, the project fuses together adventure, craft, anthropology and art. The setting was very different though: a mythical river that features so powerfully in Hollywood movies and in the history of the United Stated. The expedition attempted to reveal the many layers of American history associated with Mississippi: enduring racial inequality, colonialism, monocultures, pesticides and GMO seeds as well as the adventurous stories of Mark Twain.