For its 11th edition, the KIKK in Town exhibition, part of the KIKK festival in Namur (BE), has once again been spreading its installations and uncanny experiences all over the city. In a desacralised church, in schools, at the Museum of Decorative Arts, in a concert hall, etc.

KiKK In Town exhibition. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

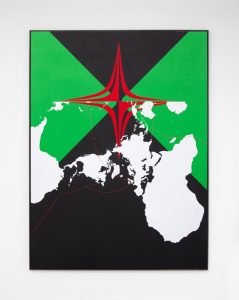

Haseeb Ahmed, The Library of the Winds (Werktank & Overtoon showcase), 2022. Photo: KIKK Festival

Shivay La Multiple, Zebola. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

This year, the theme of the event attempts to counterbalance all the doom and gloom that jumps down our throats each time we open a newspaper or our Twitter feed. Asking us to leave behind the darkness of daily news streams, the KIKK festival weaves “tales of togetherness” and spotlights the forces and fictions that bring us together as human beings. The 60 artworks selected for KIKK in Town strike a fine balance between the universal and the individual, between the common communication modes that allow us to communicate even when we speak different languages and the cultures and backgrounds that make each of us different and interesting.

One of the characteristics of the KIKK festival is that it is joyful, bright and friendly. For some 48 hours, while I was there, I forgot that the country were I live is now governed by a far-right coalition, that there’s war in Europe and the sunny sky over Namur was an unsettling abnormality.

The work that embodied the best the theme of KIKK for me was Anouk Kruithof‘s Universal Tongue.

Anouk Kruithof, Universal Tongue, 2018-2021. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Anouk Kruithof, Universal Tongue, 2018-2021. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Anouk Kruithof, Universal Tongue, 2018-2021. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Anouk Kruithof, Preview Universal Tongue Mass

From twerking to Argentinian tango, from voguing to flash mobs, from Cuban abakúa to the Zimbabwean sungura and more. All the dances of the world are on social media. Artist Anouk Kruithof worked with 52 researchers from all over the world to study dance videos on YouTube, Facebook and Instagram. Together they compiled 8,800 films and identified 1,000 different dance styles in 196 countries.

These dance styles are brought together in an eight screens installation that features a total of 32 hours of found footage, arranged by rhythm and number of dancers (“solo, duo, group or mass”.) The films are accompanied by a four-hour-long soundtrack compiled from the music found in the film footage. The different choreographies, styles, contexts and modes of expression are united by the same music. What i found almost magical about the installation is that dancers you would normally dismiss such as the fat guys in pink ballet tutus and the skinny guy frolicking in a fluoro green lycra suit look magnificent in this context. You just want to dance and be like them: ecstatic and insouciant.

This visual anthropology of world dance offers a window into the diversity of the world. It shows dance as both a unifying mode of expression and one that is rich in moods and nuances.

Pepa Ivanova, Decay, 2018

Part of the KIKK In Town programme, the Biotopia exhibition extends this year’s festival celebration of both diversity and universality to non-human life. The show “proposes to shift points of view, to immerse ourselves in the heart of non-human societies and to open ourselves to the diversity of ways of being.” Reading the sentence made me wonder why Aki Inomata‘s Why Not Hand Over a “Shelter” to Hermit Crabs? was selected for the show. If you do adopt the point of view of a hermit crab, you soon realise that the poor creature doesn’t deserve to be isolated in a small water tank in the company of a few rocks and fancy plastic artefacts, under spotlights and the gaze of visitors. The hermit crab is, unlike its name suggests, a social creature. They live in groups and are probably much more comfortable in the wild than in an exhibition space.

Speaking of sea creatures, there were two other works in that same exhibition that I found particularly interesting:

Jean Painlevé, La pieuvre, 1928. Study of the octopus in its habitat

Jean Painlevé. Photo

I was completely fascinated with Jean Painlevé‘s La pieuvre, a short popular science documentary that described the life and behaviour of an octopus.

A prolific photographer and filmmaker with a solid scientific background, Painlevé shot more than two hundred films between 1925 and 1986. He demonstrated a sense of innovation in both his use of technology and his exploration of the documentary style. For example, in order to shoot scenes underwater, Painlevé strapped to his chest a camera encased in a custom-designed waterproof box fitted with a glass plate for the lens.

Painlevé filmed La Pieuvre in Port Blanc in Brittany. Influenced by the Surrealists, Painlevé developed a filmic visual language that questioned the anthropocentric orientation of scientific documentary films. In short sequential scenes, his images develop a narrative about the anatomy, behaviour and abilities of an octopus, but they also raise awareness of the brutal impact humans exercise on these animals. The film also manages to communicate the magic and intelligence of the octopus with scenes that have a surrealist undertone: when an octopus clasps a human skull in an aquarium or slips down from a tree, or when the camera lingers on the extraordinary eyes of the marine creature.

I loved the dialogue between La Pieuvre and Lia Giraud’s use of photosensitive microalgae:

Lia Giraud, Photosynthèse, Installation Algægraphique, 2021

Lia Giraud, Photosynthèse, Installation Algægraphique, 2021. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Since the early 2010s, Giraud has been developing a technique that uses light-sensitive microalgae to produce images. She calls this photographic process “Algaeography”.

Photosynthèse, Installation Algægraphique consists of a tubular structure that houses six bioreactors in which micro-algae cultures are growing. On a screen, thousands of objects fished out of the port of Marseille between 2016 and 2020 by the MerTerre association appear like slow-moving ghosts. The film also demonstrates how the microalgae, often used as a marker of pollution, replace the photographic silver “grain” to reveal an image that is alive.

By blurring the frontiers between biological and digital, the installation invites the viewer to reflect on what it means to live in an age deeply shaped by science and technology.

Several other artworks explored the intimate sphere in ways that were either quite sensuous or disturbingly thought-provoking.

Roel Heremans, The NeurRight Arcades (Werktank & Overtoon showcase), 2022. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Roel Heremans, The NeurRight Arcades, 2022

Roel Heremans, The NeurRight Arcades (Werktank & Overtoon showcase), 2022. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

One of the few critical artworks in the festival, The NeurRight Arcades casts an acute gaze over the ethical implications of neurotechnology.

Neuro-wearables and BCIs (Brain-Computer-Interfaces) will soon be as widespread as other body-worn sensors that track heart rate, sleep-wake cycles and other bodily data. They are currently used for general health monitoring, entertainment or in military contexts. Once they have entered the consumer market, wearable devices that monitor brainwaves will be able to control electronic devices by thought.

As often happens with consumer electronics, innovation is moving faster than legal and ethical frameworks. It is therefore crucial to look critically at the human rights and ethical implications of neurotechnology before it is too late. Researchers at Columbia University have identified five NeuroRights to protect the human rights of all people from the potential misuse or abuse of neurotechnology: the right to Mental Privacy, Personal Identity, Free Will, Equal Access to Mental Augmentation and Protection from Algorithmic Bias.

Roel Heremans has created an installation of five arcade machines that make these NeuroRight more tangible for participants. Wearing a real-time BCI headphones, participants are guided through an aesthetic experience where their mental state is transparent. Each of the arcades offers a unique experience mixing sound, composed introspection and neurofeedback that pushes visitors to realise the need for a legal and ethical framework around the use of Brain-Computer Interface before it is too late.

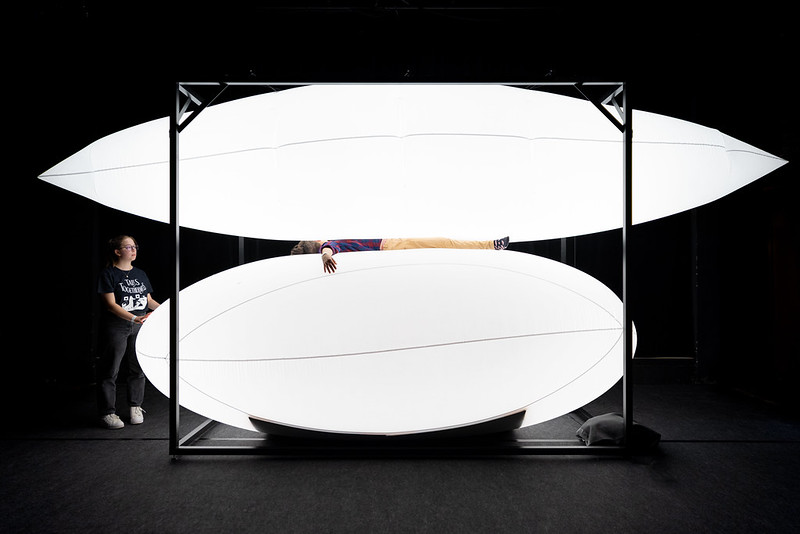

Teun Vonk, The Physical Mind, 2016. Photo: Trystan Lothaire

Teun Vonk, The Physical Mind, 2016. Photo: Trystan Lothaire

Teun Vonk, The Physical Mind, 2016. Photo: Kat Closon

The Physical Mind installation is like a massive but ultra-light weighted blanket. The pressure of weighted blankets are said to put your autonomic nervous system into “rest” mode, lowering stress and anxiety and providing an overall sense of calm.

Teun Vonk’s own version of this type of deep pressure therapy lets participants experience the relation between their physical and their mental states by applying physical pressure to the body.

You lay down on a deflated white cushion. It then inflates at the same rhythm as a similar cushion on top of you. As you get lifted up, you are gently squeezed between the curves of the two objects. While the lifting creates an unstable feeling, this stressful sensation is soon contrasted with the secure feeling of being gently hugged by two soft objects.

Xavier Machault, Only You. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Xavier Machault, Only You. Photo: Kat Closon

I’ll end this ultra fast tour of the KIKK In Town exhibition with a work put me in a good mood. Taking its name from the famous O-oHHHH-nly you song by The Platters, Xavier Machault’s installation offered passersby the possibility to take a moment off their daily routine and enjoy a love song broadcast just for them inside a cosy little cabin that doubles as a jukebox.

Visitors can select one track among 16 iconic love songs. They sit down inside and for a few minutes the song is played for their sole pleasure. I love the music selection as most of the songs are either absolutely unbearable (to me), joyful or likely to make you want to throw yourself in the nearby river out of despair and chagrin. The installation made me think about the love songs that I enjoy. Non ironically. I realised I couldn’t think of any. Apart from a couple songs by Serge Reggiani. They are so dark I won’t even name them though.

Many more photos from the KIKK festival:

Agnes Meyer-Brandis, One Tree ID, 2019. Installation view at BIOTOPIA, Pavillon. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Agnes Meyer-Brandis, One Tree ID, 2019. Installation view at BIOTOPIA, Pavillon. Photo: Kat Closon

Agnes Meyer-Brandis, One Tree ID, 2019. Installation view at BIOTOPIA, Pavillon. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Lukas De Clerck, AirBag/14Holes (part of Werktank & Overtoon showcase), 2020. Photo: KIKK Festival

Linda Dounia, Spannungsbage, 2022. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Caroline Robert, Brainstream. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

ECAL / University of Art and Design Lausanne, Playful Lab, 2019-2022. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Camille Scherrer, In The Wood, 2011. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

KIKK Conference. Photo: Gaëtan Nadin

KIKK Conference. Photo: Gaëtan Nadin

KiKK In Town exhibition. Photo: Quentin Chevrier

Previously: How to become a tree for another tree, ISEA 2022: Porn and ecoporn in digital arts, Bio-fiction Science Art Film Festival. Part 1: short fiction films about neurotechnology, Bio-fiction Science Art Film Festival. The neurotechnology edition (part 2).