After last week’s Notes from the RIXC Open Fields conference, it’s time to have a quick look at the accompanying exhibition of this year’s edition of the RIXC Art Science Festival.

The theme of the exhibition, curated by Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás and Bernhard Serexhe, is encapsulated in its title: Global Control And Censorship.

Ruben Pater, Drone Survival Guide, 2013. Photo: RIXC

The curators wrote in their introductory text to the exhibition:

Surveillance and censorship are mutually dependent; they cannot be viewed separately. It has always been well known that the surveillance of citizens, institutions, and companies, indeed, including the monitoring of democratically elected politicians and parliaments or of journalists and lawyers, is a secret task of government agencies. Recently, however, this tradition of government-legitimized spying on all citizens has expanded to include additional spying by powerful service providers and business enterprises. At the same time, courageous journalists, who disclose information that carries enormous importance to society such as illegal surveillance activities, censorship and torture by governmental institutions, are prosecuted and punished. Even in our day, journalists, artists and writers critical of the system and whistle-blowers are branded as traitors.

The exhibition is not ground-breaking* but it is solid, coherent and thought-provoking. I was particularly impressed by the way the curators take us from one location to another, showing how surveillance encroaches on freedom of movements, communication and actions no matter where we are on the planet. Sometimes the means of surveillance and their impact seem to be site-specific. Often though, they replay the same patterns of scrutiny and blackout that have been adopted everywhere else.

Here are some of the works i found most interesting:

Osman Bozkurt, Post Resistance, 2013

Osman Bozkurt, Post Resistance, 2013

Photographer Osman Bozkurt documented the remains of the slogans, drawings and other signs that were painted onto the surfaces of public spaces in Istanbul at the time of the Gezi Park demonstrations in Istanbul in 2013.

That Summer, thousands of citizens occupied the park to oppose its proposed demolition as part of an urban development plan. The police’s violent response to the unrest provoked strikes and further protests across the country, with citizens expressing their disapproval of large-scale urban and economic changes proposed by the government, attacks on freedom of the press and of expression, the encroachment on Turkey’s secularism and Erdogan’s authoritarian measures. The movement was eventually dispelled by the brutal governmental riposte, leaving many people injured or imprisoned.

Authorities made sure that the protests slogans and signs on the walls were swiftly painted over. Boskurt documented the grey patches that haunt the areas surrounding the unrest. They remain as ghosts of attempts to defend the rights to a fair society.

aaajiao, GFWlist, 2010. Photo: RIXC

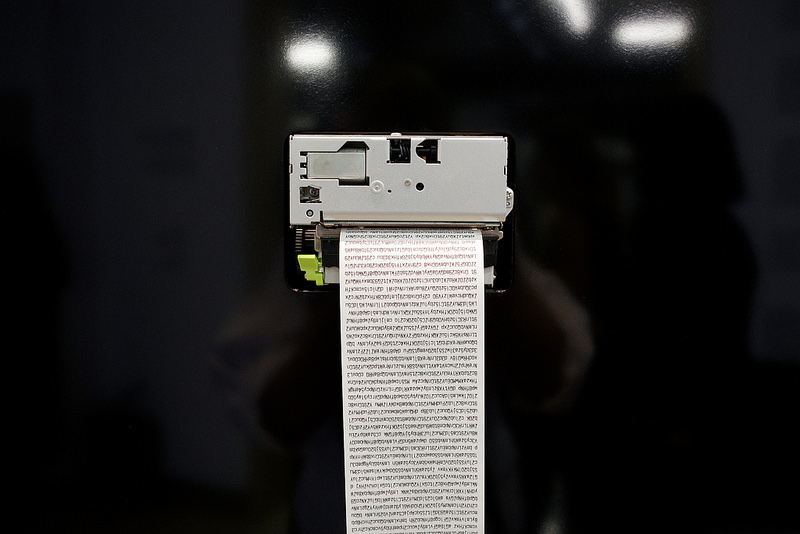

The Great Wall of China, an over eight thousand kilometers-long series of fortification, was built to protect the Chinese states and empire against raids and incursions by nomadic peoples. Its information age equivalent, the Great Firewall of China, was engineered to regulate the Internet domestically and keep unwanted information, ideas and images out of the Chinese Internet. Both Chinese and foreign websites and news stories are censored by the GFW mechanisms.

GFWlist, by artist and activist Xu Wenkai aka aaajiao, is an installation that relentlessly prints the URLs of the websites that are banned on the Chinese Internet. A printer spits out the list on a long scroll of paper that falls down and forms a heap onto the floor. The printer is perched on a black monolith similar to the one that puzzles prehistoric humans in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 movie A Space Odyssey. The meaning of the monolith remains a mystery for most film critics. Some like to interpret the structure as a trigger of self-awareness in the early humans and thus the beginning of civilization.

Because China prohibits to even publish the list of the blocked web-addresses, aaajiao’s installation stands as a poetical but explicit message of civil disobedience.

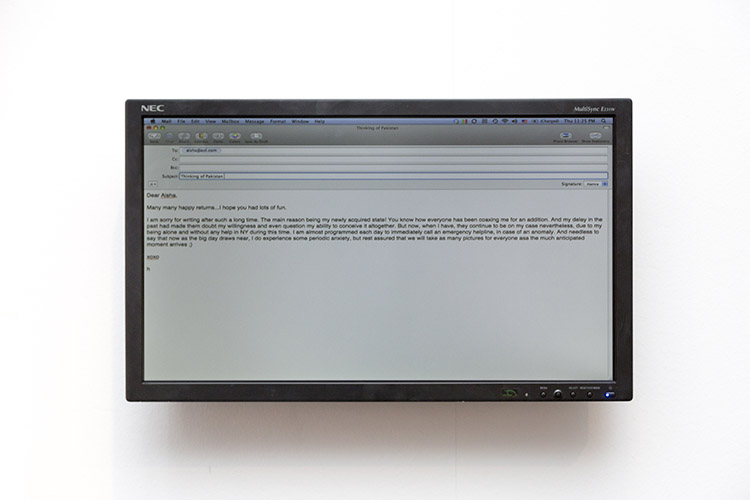

Hamra Abbas, Text Edit, 2011

Hamra Abba’s video is simple and incredibly moving. The screen shows an email in the process of being written by a woman who is announcing her pregnancy to a friend. While composing her message, the writer keeps erasing and correcting her words, self-censoring for fear that her words might be monitored and misinterpreted. Her joke about how people “terrorized” her into having a child is being amended so that the word “terrorized” becomes “coaxed”. Similarly, words like ‘blast’ or ‘chaos’ suddenly take an ominous meaning and she quickly erases and replaces them.

Such is her fear of the possibility of being under surveillance, that the final version of her message is brief but bland and devoid of any of the joy you would expect in such circumstances.

Daniel G. Andújar, Let’s Democratise Democracy, 2011-ongoing

Daniel G. Andújar, Let’s Democratise Democracy, 2011-ongoing. Photo via think commons

During the celebration of Labor Day and then again the day before Spain’s general election in 2011, Daniel G. Andújar rented a small plane and flew a banner that said Democraticemos la democracia (Let’s Democratise Democracy) from Murcia to Alicante. His yellow banner reappeared several times in Spain that year. The slogan was translated and brandished in places as diverse as the Ministry of Defense in Belgrade, the nuclear shelter of Tito in Bosnia Herzegovina or a refugee camp in Western Sahara. Whether his slogan takes the form of stickers, posters, graffiti, flags or installations, it always adapts and takes a new meaning and target with each location. Depending on the context, the Let’s Democratise Democracy slogan is interpreted as a challenge to corruption, inflation, expulsions, surveillance, etc. The motto works no matter the type of attack on democracy.

Because the artist believes that public space belongs to everyone and that it must be continuously conquered from hegemonic attempts to control it, he encourages passersby who stumbles upon his project to document it with their phone and spread the message further.

Marc Lee, Security First, 2015. Photo: RIXC

Marc Lee, Security First, 2015. Photo: RIXC

Marc Lee, Security First, 2015

Marc Lee shows displays “the wonderful world of surveillance technology.” The array of surveillance cameras he lines up on shelves is completed by a monitor showing the website insecam.org. While the cctv apparatus is sold as the gateway to protection and peace of mind, the directory of online surveillance security cameras reminds us of the threat these cameras present for our privacy.

More works and images from the Global Control and Censorship exhibition:

Dan Perjovschi, Drawings, 1995–2015

Dan Perjovschi, Drawings, 1995–2015. Photo: RIXC

View of the exhibition space. Photo: RIXC

Erik Mátrai, Turul, 2012. Photo: RIXC

Ma Qiusha, Twilight Is the Ashes of Dusk, 2011

View of the exhibition space. Photo: RIXC

Also part of the exhibition: Peters Riekstins, Back to the Light.

The RIXC Open Fields conference, organized by RIXC the center for new media culture, is over but if you’re in Riga, don’t miss the accompanying exhibition: Global Control and Censorship. It’s at the National Libary of Latvia until 21 October 2018.

More images of the exhibition opening in RIXC’s flickr album.

* i think i will always miss the extraordinary bite and vision that Armin Medosch was bringing to the RIXC festival.