3rd and final part of my report from the conference AMBIVALENCES #1 which took place in early October in Rennes in the framework of the Maintenant digital art festival. Part 1 outlined Bénédicte Ramade’s overview of the History of Ecological Art. Part 2 highlighted key moments from the round table “Digital Arts and Environmental Awareness” that discussed the ambivalent relationship between digital artists and the environmental crisis.

Brandon Ballengée, DFA 147: Phaethon, 2013. Cleared and stained Pacific tree frog collected in Aptos, California in scientific collaboration with Stanley K. Sessions. Part of Malamp: The Occurrence of Deformities in Amphibians, 1996-Ongoing

This final chapter sums up the notes I took during Manuela de Barros‘s keynote lecture “On the notion of ambivalence in the relationship between arts, technology and society” (the video recording of the talk is here, it’s in French and the interesting part starts in 08.40)

Manuela de Barros is a Lecturer in Art History and Aesthetics at Université Paris 8. In her talk, the philosopher and art theoretician attempted to show that while ambiguities, complexities and even equivocations abound in artworks, they do not invalidate the artistic proposals. They are part of the creative questioning that artists bring to technology and to a world uncertain about its future.

The continuous dialogue between art and science, de Barros explained, is an economic and probably also an anthropological necessity.

Manuela de Barros. Keynote at Ambivalences – Espace Tambour. Photo: RAWR.prod

1816 was The Year Without a Summer. The severe climate disruptions were caused by the volcanic eruption of Mt Tambora on the Indonesian island of Sambawa. The eruption has been linked with drastic weather changes in North America and Europe, with frosts in June and heavy rains throughout the summer in many areas. This led to food shortages, which may have prompted westward migration in America and, in a Europe led to widespread famine. That year, Mary Shelley imagined the story of Frankenstein. John William Polidori started devising the figure of the vampire. The characters bring out ethical and philosophical questions such as the definition of what is human, the obligations we have towards our ontology and the question of our possible rights to modify it. They also interrogate our relationship to the environment. Today’s visual artists follow in the 19th Century writers footsteps.

In her keynote, Manuela de Barros explored the limits of Earth resources, the responses to climate change, the sharing of a limited territory with non-human beings, the energy and ecology transition and other environmental issues through the lens of artistic proposals. Her keynote was articulated around 4 main themes:

– climate change and geoengineering,

– food crisis and animal sentience,

– biosciences and the transformation of the living,

– degrowth, energy transition, co-responsibilities, post-colonialism or the colonisation of oceans and space.

1. Climate change and geoengineering

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein can be interpreted as a warning against the power of science and our obsession with modifying nature. In the novel, nature and science have a life/death relationship. Science uses and instrumentalises nature but it can also devastate it. The use that Victor makes of science, for example, is the motor of his own destruction. However, nature itself can also be violent and blind. Both science and nature yield immense destructive power.

Today, Shelley’s nature doesn’t exist anymore. The Capitalocene has affected all the places, all the inhabitants of this planet. Even the most remote locations and beings have, to some degree, been impacted by climate change. One such remote area is the Far North.

Rihards Vitols, Anniu, 2018

Powered by a solar panel and two mini wind turbines, the Anniu boat produces ice cubes. The vessel would roam around the Antarctic and drop the ice cubes into the water in order to slow down the melting of the ice cap and the rise of sea level. Could technology save a planet damaged in part by technology?

Art Orienté Objet, La peau de chagrin, 2009-2010

Art Orienté Objet explored the ambivalence of our reaction to Climate Change. A polar bear raises its paws towards a sky made of bulbs that symbolise global warming that kills both the bear and its habitat. A sensor lightens up the installation as visitors come near, involving them in the narrative. The bulbs selected by the artists are supposed to allow for energy saving. However, they contain soil-polluting mercury, they heat up the room and they gave rise to new industrial developments that greatly enrich their manufacturers. Arctic (which comes from the Greek arktos, “bear”) has become the land to exploit for resources that will be extracted and exploited to keep the industrialisation drive high and will this contribute to the thawing of permafrost and ice caps.

Other artists are interested in geoengineering, an industry that might further disturb ecosystems while keeping alive the myth that we don’t have to make any substantial efforts in order to enjoy both infinite growth and a healthy planet.

Marie-Luce Nadal, La Fabrique du Vaporeux n°1, 2014

Marie-Luce Nadal, La Fabrique du Vaporeux n°1 / Factory of the Vaporous n°1, 2014

Marie-Luce Nadal found out a few years ago that geoengineering is nothing new in rural areas. In fact, her family of wine producers has been intervening on cloud formation for at least 3 generations. In his diaries, her grandfather wrote down the weather, the risks for crops but also how he was using a hail cannon to disrupt the formation of hailstones in the atmosphere. It’s a type of geoengineering on a micro-scale.

Made using materials recycled from an old alcohol distillery, The Factory of The Vaporous No. 1 is a portable machine to capture clouds. Half-utopian half-serious, The Factory of The Vaporous is composed of a system that extracts air and water, a set of instruments that separate the air and water from their chemical and inorganic components, as well as a series of tools which allows her to measure and mix these components with the aim of producing pure essence of cloud and synthetic thunderstorm.

Marie-Luce Nadal, Extracteur de foudre portatif et munitions de foudre

Marie-Luce Nadal, Lightning ammunitions

The lightning extractor backpack is another far-fetched machine. This one is designed to find and capture lost lightning strikes wherever they occur. So far, Marie-Luce Nadal has collected 114 lightening strikes that are stocked inside munitions.

2. Food crisis and animal sentience

In her 1962 essay Silent Spring, Rachel Carson told the public how DDT pesticides had killed birds and silenced the US rural landscape. A similar silence is falling over forests, seasides and other “natural” spaces. Three of the key aspects brought to light by Carson are still very much alive almost 60 years after the publication of her book: environmental destruction, lack of interest and deceit on the part of the industries involved and the defection of the states.

Jacques Loeuille, Birds of America, 2018

Jacques Loeuille followed in the footsteps of ornithologist and father of US ecology John James Audubon who, in the 19th century, made an inventory of all the birds in the Mississippi. Loeuille notes that many of the birds that Audubon had drawn have now disappeared.

Birds of America is made of 7 films, each of them is dedicated to a bird that has left the territory. With their departure, it is the mythology of the USA that is eroded. The Bald Eagle, for example, was adopted as the national bird symbol of the USA in 1782. It was in danger of extinction until recently due to habitat destruction and degradation, illegal shooting and the contamination of its food source, largely as a consequence of DDT. No longer endangered, the Bald Eagles are now protected by multiple federal laws and regulations.

Loeuille’s work shapes a counter-history of the politics of the United States from an environmental point of view and questions the impact that species extinctions and environmental damage have on the image and identity of a country that is supposed to be the most powerful in the world.

Magali Daniaux & Cédric Pigot, Devenir Graine (Becoming Seed), Action in front of the Global Seed Vault in Svalbard, Longyearbyen, Mai 2012

Food, along with water, air and the sand necessary to make concrete, is the most important resource humans need to survive. It is also at the origin of world instability, mass migration, hunger, violence, etc. The way we produce, eat and waste food is a major cause of environmental degradation.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault promises to provide the world with a “backup” for seeds from crop varieties growing across the world. Opened in 2008, the facility is managed by the Norwegian government, the Crop Trust and the Nordic Genetic Resource Center (NordGen). It is also financed by various governments and by organisations and donors such as the Foundation Bill and Melinda Gates. What does it mean to entrust private enterprises with the ownership of seeds which are at the source of animal and human food? Especially when you know that food constitutes a potential political and economic weapon?

As Magali Daniaux & Cédric Pigot explain in one of the projects they made about the Seed Vault, the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard is located North of the Barents Sea, where prospecting for gas and oil reserves takes place, and inside the Arctic circle, which provide a metaphorical illustration of the relations between man and nature. The vault encapsulates some of the most salient geopolitical and geostrategic issues: global warming, cross-border collaborations but also diplomatic tensions between Norway and Russia, the management of fossil fuel and nuclear resources, the development of GMOs and the commercialisation of living things.

3. Biosciences and the transformation of the living

Discourses about animals emerge from fields as diverse as biology, ethnology, sociology, ethics, literature or even religion. None of these disciplines adequately covers the irreducibility of the ambivalent relationship we have with animals: they are both food and life companions, they are linked to nature and they are radically instrumentalised by industry and commerce. What happened to animality with the loss of nature?

“The question is not, Can they reason?, nor Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being?”

– Jeremy Bentham (1789) – An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation.

Bentham places the animal question in the context of a general liberation that involves humans as well.

Animals have various status and roles for humans. Domestic animals (either pets or butchered) belong to the human sphere. The risk for them is to lose their animality. As for wild animals, whether they are living in the wild or in captivity, it’s their wildness that is under threat, their ability to survive without any (deliberate) human intervention. But the wildness of a lion is not the wildness of a shark which is not the wildness of a fly. Meanwhile, lab animals sometimes start their life as pets or wild animals and become mere things. The paradox is that we use animals in laboratories because we cannot use humans for ethical reasons. And yet, we select these animals because they are biologically close to us and thus their reactivity (among others neurological or even their behavioural reactivity) is close to ours.

In art too, the animal plays an important role. It was one of the very first subjects of artists (think of cave paintings), a material, an actor of the work and a material for conceptual reflection.

Artists who use biotechnology often interrogate what in our present already constitutes the future and operate a real anthropocenic repositioning. Their work repositions the human within the ensemble of the living as an integral part of it and not only as a stakeholder. These artists not only flatten the classical hierarchy that puts the human at the top of the ladder above other animals and plants, but they also challenge old conceptions by taking into account forms of life usually neglected, such as bacteria and viruses. In their works, the often forgotten oceanic continent is finally getting the attention it deserves.

Robertina Sebjanic, Aurelia + Hz Proto Viva Generator, 2015

Robertina Sebjanic uses jellyfish to explore the possibilities of coexistence between animals and machines but also to directly interrogate the 6th wave of mass species extinction. Jellyfish have inhabited the oceans for 500 million years. Because of their longevity, their genetic characteristics are of great interest to the cosmetic and the pharmaceutical industries. So while in the near future some might enjoy an ultra-long life, others (humans or non-human) will struggle to survive. Sebjanic’s installation questions the capitalist biopolitics and the possibility of radically reforming the means and objectives of biotechnologies in order to redefine social values and improve interspecies relationships.

When the installation was exhibited in Paris, the jellyfish were adopted by the Paris aquarium. Works like this also raise the issue of the use of animals in artworks.

4. Degrowth, energy transition, co-responsibilities, post-colonialism or the colonisation of oceans and space

Some artists chose to comment on technology while using DIY, recycling, low tech, development of new materials in order to comply with the rules of sustainable development.

DaniauxPigot, Cthulhu, 2020

Cthulhu, for example, is a tactile, pink stoneware reference to Donna Haraway’s critique of the human exceptionalism contained in the concept of the Anthropocene and call for an emphasis on multispecism.

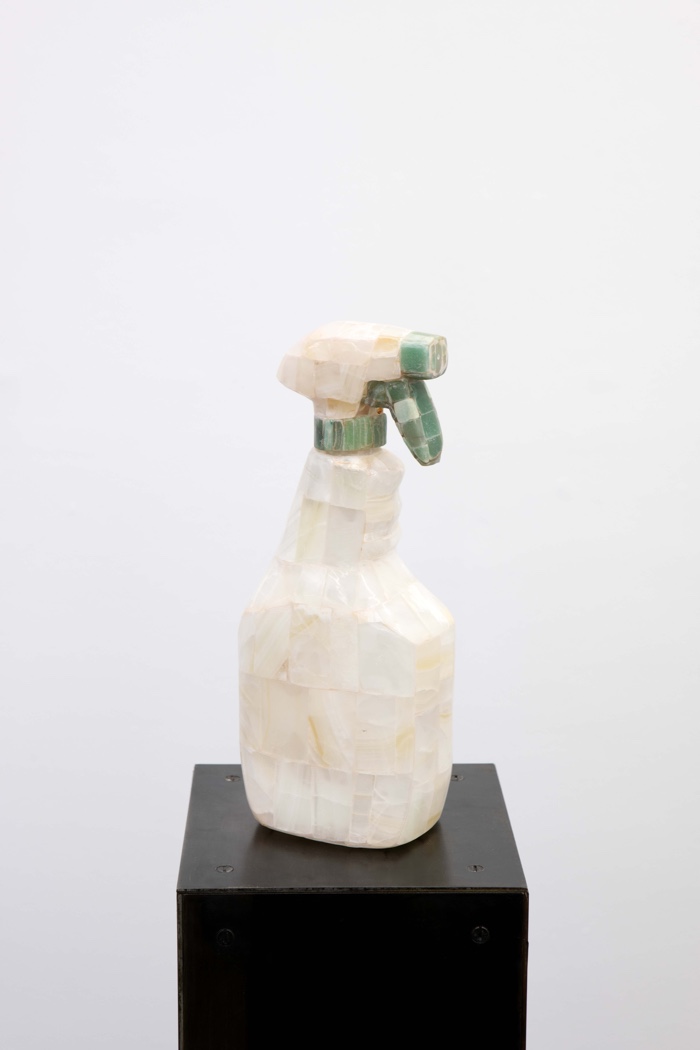

Théo Mercier, Déjeuner sous l’herbe (Ajax triple action), 2020. From the series Silent Spring. Photo: © Erwan Fichou

Théo Mercier, Déjeuner sous l’herbe (Total), 2020. From the series Silent Spring. Photo: © Erwan Fichou

Théo Mercier’s sculptures address current ecological concerns by using precious materials to reproduce the most mundane and polluting objects of our daily life, giving plastic artefacts a nobility they have long lost.

Neither of the examples above constitutes a reactionary return to traditions. Instead, the works explore through organic media the consequence of a society that so heavily relies on technology.

Manuela de Barros also found some time to look at Space Art and its inherent ambiguities. Even artists who have deep ecological concerns can create works that leave planet Earth and operate in zero gravity (producing thus works that have a high energy cost.)

Makoto Azuma, Exobiotanica 2 -Botanical Space Flight, 2017

Ikebana artist Makoto Azuma launched flowers and other plants in orbit. He put them in space with the help of two vessels, a team of 10 people and JP Aerospace, a company that developed a volunteer-based DIY Space Program.

de Barros drew pertinent parallels between the colonisation of space and the colonisation of oceans which threatens to further weaken and impoverish ecosystems already affected by plastic waste, overfishing, rise in greenhouse gases, etc.

The artworks she selected have the ambition of demonstrating the power of an imagination powered by science and technology but they also show how difficult it is to change the world when you are an artist with only limited funding. Thinking, creating, developing new forms, she said, requires independence, in particular financial independence. Environmental issues are essentially economic and political. That is why she ended her keynote with works by artists who engage directly with our daily life and with the power relations in a democracy.

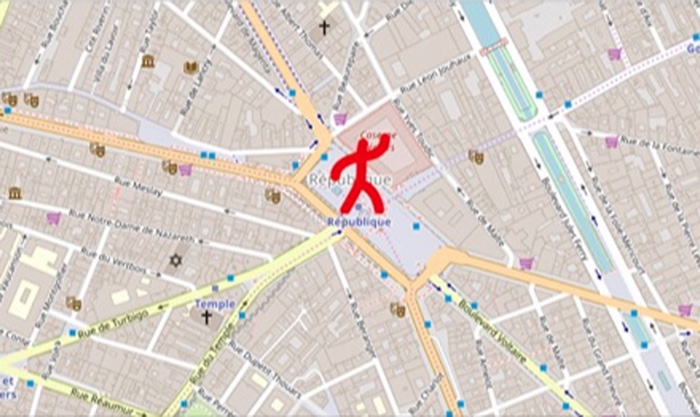

Antoine Schmitt, manif.app

manif.app is a tool developed by artist Antoine Schmitt during the violent manifestations in Paris last Winter and then during the first 2020 lockdown. The website allows people unable to join a manifestation, a protest or a demonstration to show their support virtually. Their avatar is anonymised and visible publicly on the map, along with all the other avatars. Virtual protesters have the possibility to move their avatar around the map but also to hold a banner bearing the slogan of their choice.

manif.app is very successful. Last June, tens of thousands of Brazilians used it to protest against Bolsonaro’s attacks on human rights.

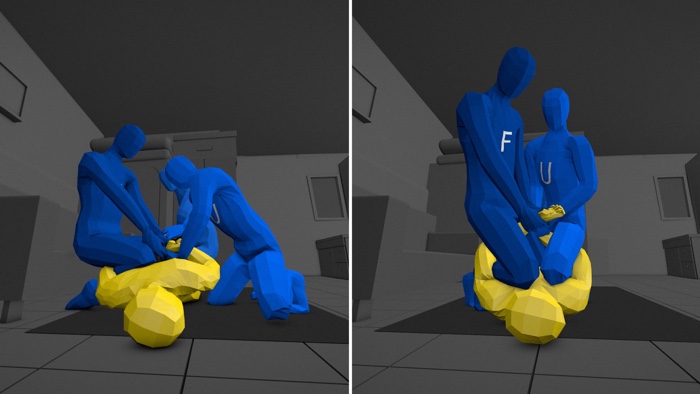

Forensic Architecture, The Death of Adama Traoré, 2020

Investigative group Forensic Architecture, whose work de Barros called “anti-fake news”, uses technologies and overlooked pieces of evidence such as the ones drawn from meteorology, eyewitness accounts and architectural reconstructions in court cases that denounce human rights abuses. Often working with NGOs and human rights lawyers, FA brings to light facts that confound the versions of events told by police, military, states and corporations. They have recently probed the death of Adama Traoré who was killed in police custody in circumstances that remain unclear.

Previously: AMBIVALENCES #1: A History of Ecological Art + Ambivalence, part 2: On the uneasy relationship between digital art and the environment.