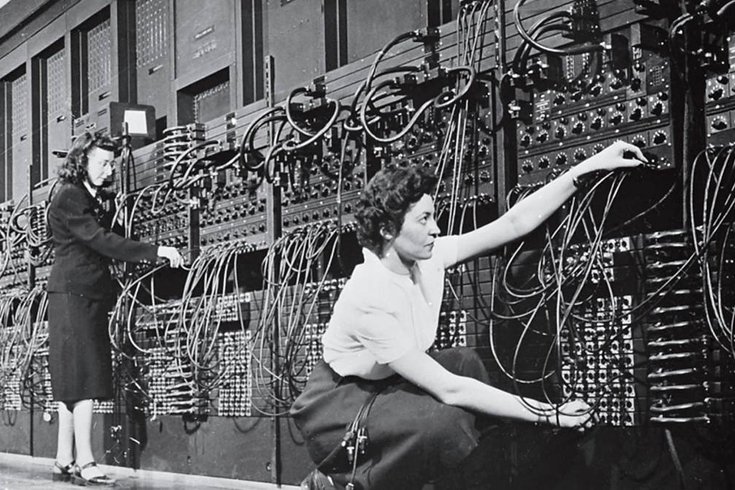

The world of computing was powered by women until men, realizing how profitable the industry was becoming, pushed women out.

The first person to be what we would now call a coder was a woman: Lady Ada Lovelace. During WWII, women were pioneers in writing software for early computers. When the number of coding jobs exploded in the ’50s and ’60s, companies looked for programmers who were logical, good at math and meticulous. And for once, gender stereotypes worked in women’s favour.

The assumption that technology is inherently male is not only historically inaccurate, it is also unhealthy, to say the least. A technology designed by white males who had access to higher education serves mostly white men, at the expense of individuals with other skin colour, gender, background, etc. And since technology is playing an increasingly crucial role in the way society is being shaped, it is important that it doesn’t reflect the mindset of only a portion of the human race. But i’m sure you already know that.

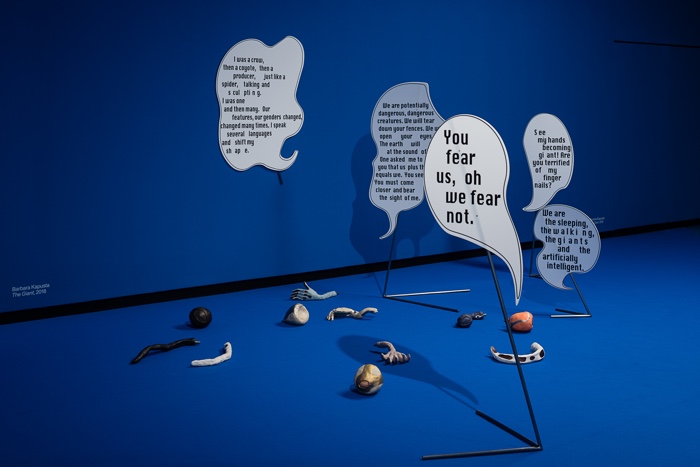

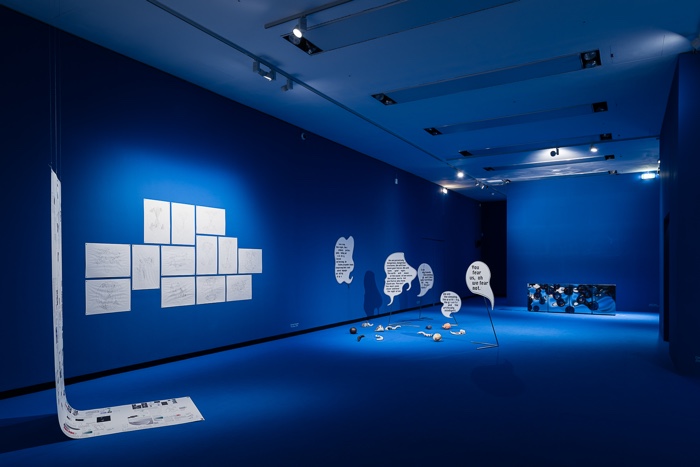

Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust

ENIAC, the world’s first digital computer, at the University of Pennsylvania, had six primary programmers: Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman. They were initially called “operators.”

A exhibition at Kunsthalle Wien, ironically titled Hysterical Mining, examines with depth and subtlety the tensions brought about by a very male techno-chauvinism. The artworks are mining, not for data or minerals, but for new meanings and strategies to approach the production and use of technologies.

“The exhibition analyses the material worlds we are creating through technology and technology’s role in shaping local and global configurations of power, forms of identity and ways of living. It draws on radical feminist and techno-feminist theories from the 1970s until now that criticised and revised the nexus tying new technologies and technoscience to patriarchal ideas.”

Hysterical Mining is a visually captivating exhibition. But it requires time if you want to fully engage with all the ideas, knowledge and nuances deployed by the artists. Any effort will be rewarded though.

Here’s a couple of artworks i found particularly thought-provoking:

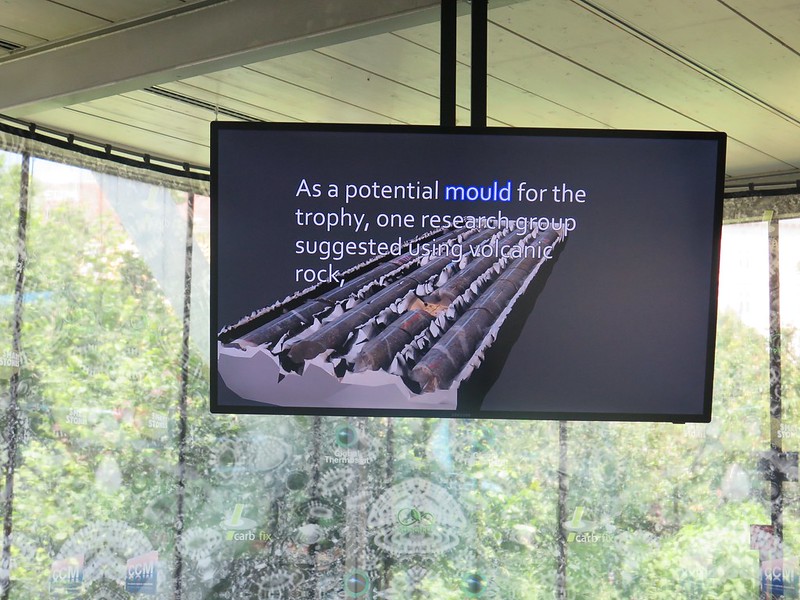

Katrin Hornek, Casting Haze, 2018–2030. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust

Katrin Hornek, Casting Haze, 2018–2030

Katrin Hornek’s Casting Haze explores the technologies of CO2 mineralization, an emerging approach which, instead of releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, would remove it from the air, store it and re-implement it into productive cycles in order to make profit out of it. The idea that such technologies could help us reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from anthropogenic point sources is seducing but it would probably be interpreted by many nations and corporations as a green light to emit even more industrial carbon dioxide, a 21st century, geo-engineered version of the Jevons paradox.

Hornek’s work not only explore the geographies, economies, industrial entanglement and philosophical grounding of the various fixations methods, she is also combining research-based analysis and artistic speculation to embody the technology in a sculpture.

With the help of scientists, the artist is planning to capture CO2 out of air or water and re-mineralize it into a sculpture. The object will be awarded (hopefully in 2030) as a trophy for the individuals or research groups who will have helped to reshape the world’s climate in the most sustainable way. The weight of the sculpture will correspond to the average one-month CO2 emission by a single human body at rest, roughly 14 kilos.

The exhibition shows a promotional video for the future award ceremony, a curtain featuring logos of companies currently involved in carbon capture, utilisation and/or storage, on a background that pictures fossils of nummulites, amoeba-like organisms that lived 55 millions years ago. The arid clay surface on the floor alludes to the changing perceptions of the relation between humans and the Earth through the ages, at a time when humans have become a powerful but uncontrollable geological force.

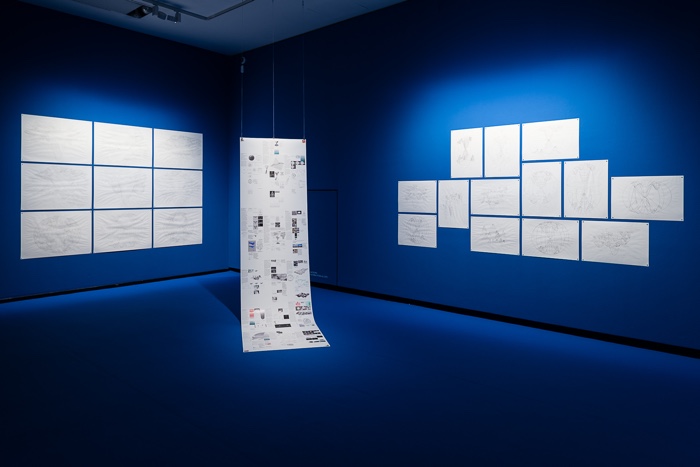

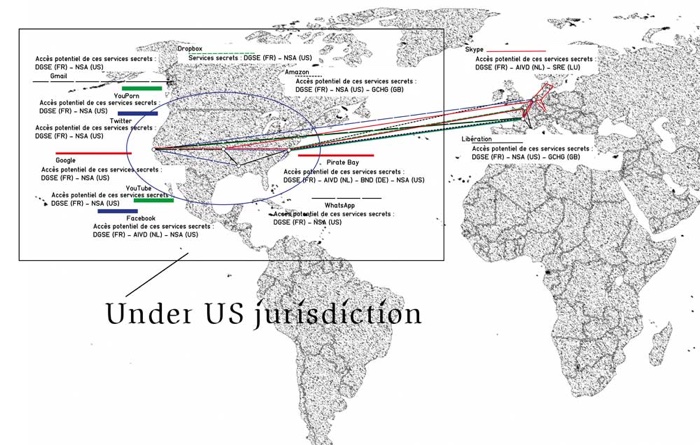

Louise Drulhe, Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015; The Two Webs, 2017. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust

Louise Drulhe, Path taken by information (network packet), depending on the service involved. Data recovered on opendatacity.de. From Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015

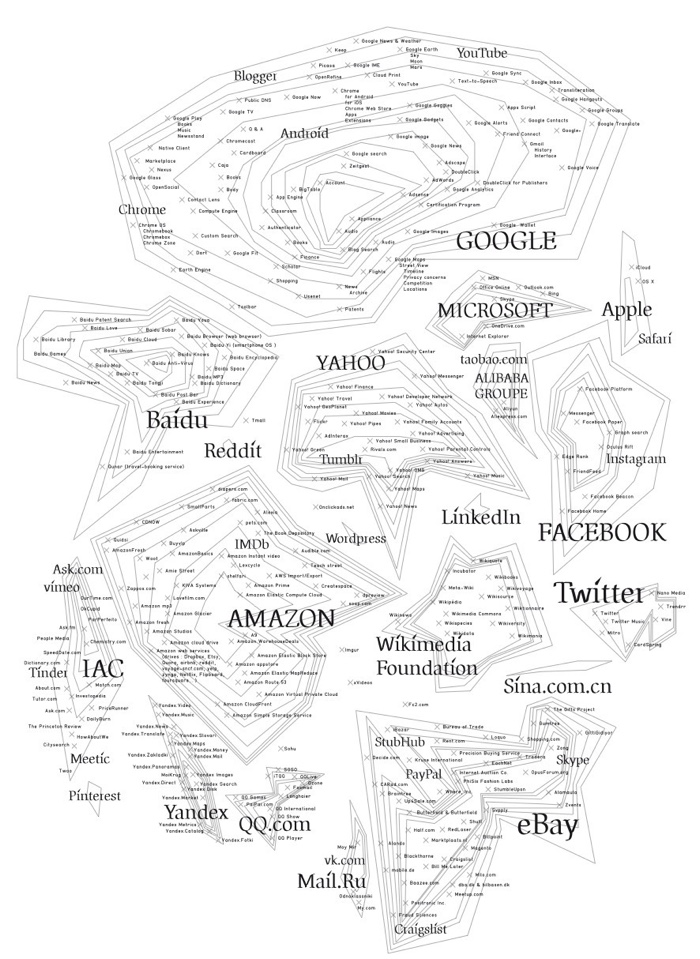

Louise Drulhe, Topographical Map. Map of the top websites (and all their derived activities), according to Alexa. From Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015

“Most people do not consider Internet as a territory,” explained Louise Drulhe in an interview with Chloe Stavrou for Furtherfield. “This idea of cyberspace is a bit old fashioned. But, I think it is still pertinent today to study Internet as a real space.”

The Critical Atlas of Internet is an eye-opening investigation of the Internet space, an attempt to represent its invisible geography and architecture.

Drulhe has developed 15 conceptual exercises that rely on drawings, schemas, objects, 3D models and videos to map the internet and give more visibility to its social, political and economic dimensions.

Though apparently whimsical, her spatialization exercises shed light on issues such as the monetization of our online gestures; the evolution from a decentralized and democratic Internet to one dominated by the GAFA; the many walls erected online (from the Great Firewall of China, to the one that separates the deep web and the “surface” web, to the borders defined by Facebook and other private networks that leave you out if you’re not registered with them); the physical occupation of the internet on earth and its hardware geography, etc.

I spent half an afternoon exploring Drulhe’s topography of Internet space and i don’t think i’ve exhausted all its lessons.

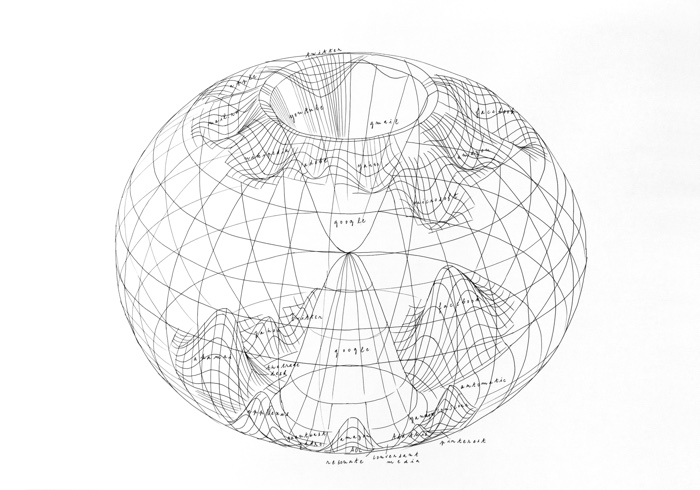

Louise Drulhe, The Two Webs, 2017. Image: © vinciane lebrun-verguethen/voyez-vous

In The Two Webs, Drulhe continues her research into the covert realities of the web.

Based on data she gathered, the artist created a series of pencil drawings that depict the disturbing symmetry between the web and the tracking-web, between the web you see and the web that is looking back at you. 90% of websites leak data to third parties, reminding you that nothing’s ever as free as it seems in the sleek world of Silicon Valley.

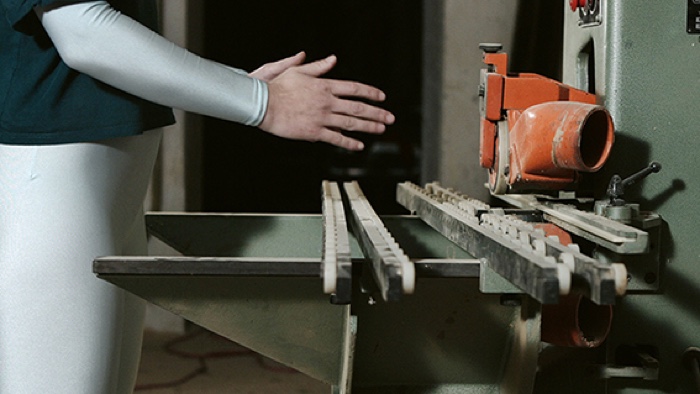

Delphine Reist, Étagère, 2007. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust

Étagère (“shelf” in English) is filled with dozens of electrical power tools that come to life as you go nearer. Behind a plexiglass sheet, the drill, circular saw, pneumatic hammer, sanding machine shake, spin, swirl, growl, roar following a kind of noisy choreography written by the artist.

They are the ultimate masculine instruments. The only time when these devices are tolerated inside the white museum and galleries rooms is before exhibitions open, when the artworks are assembled, the space refreshed and prepped for the show.

By animating the appliances in an overblown, almost frantic manner, Delphine Reist pushes our tendency to anthopomorphise the non-human to its most absurd limits. Moreover, Reist performs a work of “de-scription” (a term coined by Madeleine Akrich and Bruno Latour). In contrast to the process of “inscription” by the engineer, manufacturer or designer of a device that inscribes the object with the uses, interactions as well as the privileged user profile of the designer, “de-scription” frees the object from its initial script, decodes the alleged neutrality of the processes of manufacturing and circulation.

Judith Fegerl, The Kitchen Was What She Had Given of Herself to the World, 2019

Judith Fegerl’s sculpture, on the other hand, refers to the kind of tools and technology that are assigned to women: the kitchen appliances.

The artist subjects rectangular structures made of magnetic stain-less steel in the standardized dimensions of European kitchen modules (60 x 60 x 90 cm) to induction heating. Her intervention destabilizes their shapes and cover the surfaces with circular patterns that evoke induction cooktops. Fegerl uses the technology to leave her marks on the smooth, metallic surface, customizing the structures to her own specifications and deriding the idea that the freedom and happiness of a woman can be boosted by yet another piece of sophisticated domestic apparatus (often designed by men.)

Marlies Pöschl, Aurore (videostill), 2018

Marlies Pöschl, Aurore (videostill), 2018

Marlies Pöschl, Aurore (Trailer), 2018

How much can you automate affect? Can compassion, kindness and competence in care for the elderly be programmed? And can the human patients perceive it? Can artificial empathy assuage our fears about artificial intelligence?

Two years ago, Marlies Pöschl organised a workshop with primary-school pupils, graduating secondary-school students and senior citizens to reflect on robots that would care for our seniors. Based on the conversations, Pöschl created a semi-documentary science fiction film about Aurore, an intelligent nursing operating system that remains invisible in the film. She is the perfect carer: on call around the clock, skillful and affectionate. Yet, the film suggests, Aurore has dreams and imaginary landscapes of her own. She’s just too professional to share them.

It has often been said that the jobs that machines won’t “steal” from us are the ones that require softer skills. Nursing, for example. Yet, nursing machines might still become a necessity as populations in Western countries are ageing and less and less younger workers are eager to address the needs of the elderly. The suggestion that robots will take care of our bodies during the last years of our life remains odious to most of us but the characters in the film look happy enough to have someone to chat with.

More image from the exhibition:

Trisha Baga, Hamilton Beach, 2016; Brother Making an Impressionist Painting, 2016; Dog Bowl with Boobs, 2016; Optical 88, 2016; Thelma and Louise, 2016; William’s Wonder Bread, 2016; Microscope, 2016. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019

Veronika Eberhart, 9 is 1 and 10 is none (filmstill), 2017

Veronika Eberhart, 9 is 1 and 10 is none (filmstill), 2017

Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, 1922 – The Uncomputable (The Unmanned, Season 1, Episode 4), videostill, 2016

Fabien Giraud & Raphaël Siboni, 1953 – The Outlawed (The Unmanned, Season 1, Episode 3). Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019

Louise Drulhe, Critical Atlas of Internet, 2015; The Two Webs, 2017; Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018; Judith Fegerl, the kitchen was what she had given of herself to the world, 2019. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019. Photo: Jorit Aust

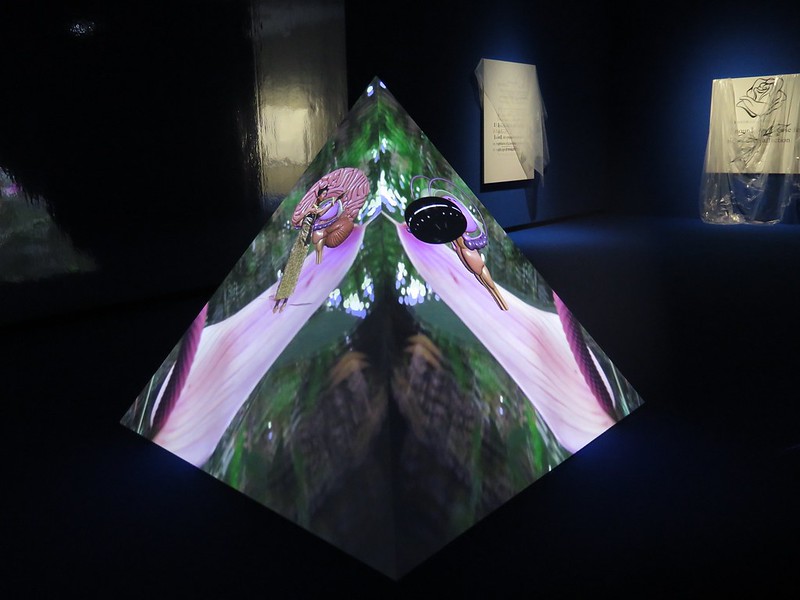

Pratchaya Phinthong, 2017, 2009; Barbara Kapusta, The Giant, 2018; Tabita Rezaire, The Song of the Spheres, 2018. Installation view: Hysterical Mining, Kunsthalle Wien 2019, Photo: Jorit Aust

Tabita Rezaire, Ultra Wet – Recapitulation (film still), 2017–2018

Hysterical Mining has two location: the Museumsquartier one immerses visitors inside a blue desktop background; the smaller one at Karlsplatz features a series of books anyone can browse to further investigate the topic of the exhibition. I highly recommend having a look exhibition guide, it is available as a PDF.

Hysterical Mining, curated by Anne Faucheret and Vanessa Joan Müller, remains open until 6 October 2019 at the Kunsthalle Wien in context of the VIENNA BIENNALE FOR CHANGE.

Related stories: Gaming Masculinity. Trolls, Fake Geeks, and the Gendered Battle for Online Culture and Algorithms of Oppression. How Search Engines Reinforce Racism.