Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

A ridiculously belated ending to my review of the exhibition Trust Me, I’m an Artist which opened in Amsterdam in Spring (god, this is embarrassing!)

The works in this group exhibition explored themes as diverse as gene editing, the preservation of nuclear culture over thousands of generations or the risks associated with medical self-experimentation. What these artworks have in common, however, is that the artistic processes and results were submitted to a specially convened ethics committee that examined the responsibilities and possible prerogatives of art.

Do artists benefit from special privileges when they engage with the methods, materials and technologies of science? Should they be entitled to more freedom when exploring biotechnological protocols and processes? Or should they be submitted to the same obligations and liability as the scientists? And finally, do art and science collaborations bring about new ethical dilemmas, new debates and challenges?

The Trust Me I’m an Artist exhibition was the result of a European research project of the same name that aimed to help artists, cultural institutions and audiences understand the ethical issues that arise in the creation and display of artworks developed in collaboration with scientific institutions.

I already wrote about some of the artworks when i visited the show in Amsterdam, here are the three last one. They are equally thought-provoking but involve performances i didn’t get to witness.

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien was born with Cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that affects the respiratory and digestive system, in particular the cells that produce mucus, sweat and digestive juices. Improvements in treatments mean patients may live well into their 40s (with some into their 50s) but there is no known cure for it. O’Brien’s private life is thus marked by a daily and intimate engagement with biomedicine. And by the presence of death.

His performance Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours used physical endurance, visceral disgust for bodily fluids and fear of contamination to confront the audience with their own uneasiness in presence of a perceived risk of infection.

The performance lasted 3 hours. O’Brien started chained to a pole in the middle of the space but gradually got closer to the audience, to the point of touching and even biting them.

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

The artist was interested in disrupting the boundaries between the spectator and the performer, and more generally between human bodies. He first broke those barriers by blowing bubbles made of water, washing up liquid and his own mucus onto the space, literally spreading his disease around. Some spectators tried to avoid the bubbles, others stood still and let them burst onto their bodies. The bubbles forced the spectators to reveal their own fears of contamination associated with the sick body.

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Martin O’Brien, Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, 2015. Photo: The Arts Catalyst

Another episode in the performance saw the artist pierce his lips. He then walked around the space with blood running down his chin, biting spectators one at a time until they pulled away. The roles were reversed in the second biting section when, naked and covered in green paint, O’Brien was chained onto a pole in a position that evoked the one of Saint Sebastian, a christian martyr commonly depicted in art tied to a post or tree and shot with arrows. Spectators were invited one by one to bite him on the body and as hard as they wanted. The ‘animalistic’ ritual gave the audience a taste of O’Brien’s skin. People suffering with CF have salty-tasting skin. The salts carried to the skin by perspiration are not reabsorbed when their body cools down.

Through this performance, the artist infected the audience. Physically, emotionally and metaphorically. Participants not only experienced a direct interaction with a chronically ill body and its bodily fluids but they also found themselves questioning the ethics of witnessing a suffering body in an art performance. They were also faced with their own physicality, mortality, fear of contamination and in most cases their privilege of good health.

Nicola Triscott, from the Arts Catalyst, wrote a fascinating text that discusses ethical dilemma of commissioning a work that engage so viscerally with the artist’s and the audience’s safety and well-being.

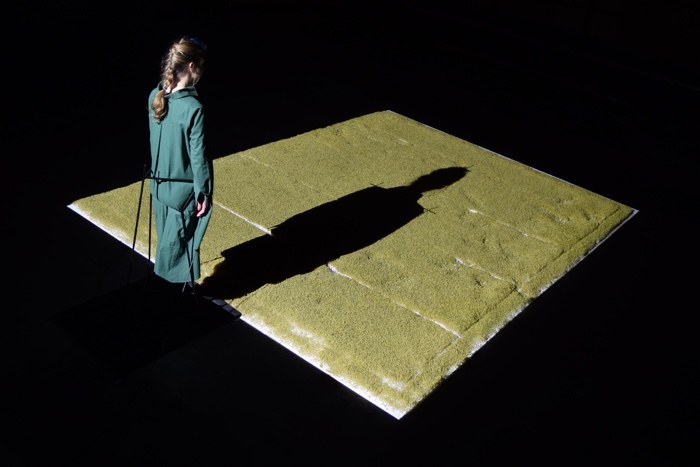

Špela Petrič , Skotopoiesis. Confronting Vegetal Otherness, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

Špela Petrič , Skotopoiesis. Confronting Vegetal Otherness, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

Špela Petrič , Skotopoiesis. Confronting Vegetal Otherness, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

Špela Petrič , Skotopoiesis. Confronting Vegetal Otherness, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

Špela Petrič , Confronting Vegetal Otherness. Skotopoiesis, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

Špela Petrič , Confronting Vegetal Otherness. Skotopoiesis, at the Click Festival in Helsingor, Denmark, 2017. Photo by Miha Turšič

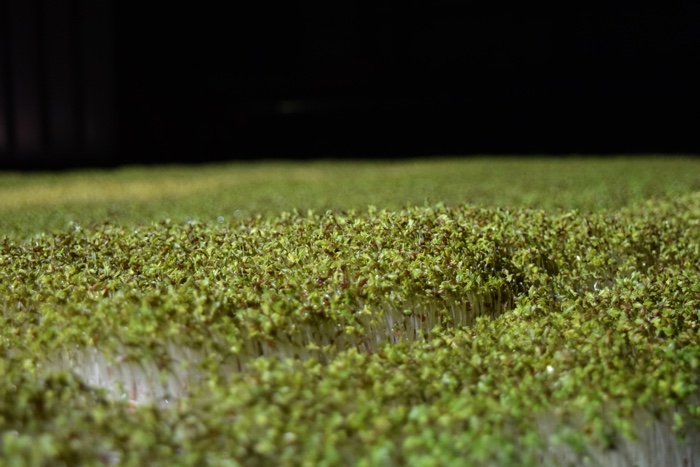

With Confronting Vegetal Otherness. Skotopoiesis (meaning shaped by darkness), Špela Petrič attempted to understand plants on their terms by submitting her body to the rhythm of the ‘vegetal aliens.’ Over the course of this 12 hour-long experiment in inter-cognition, the artist and a field of germinating cress face each other. Light is shining onto the cress but the artist’s body throws a shadow onto it. Over time, the plants growing under her shadow become paler. The effect is mediated by phytochromes, a photoreceptor and a pigment in plants, and some animals, that detects light and regulates a number of responses including the synthesis of chlorophyll. The diminished light intensity also stimulates the production of auxin, a plant hormone that promotes stem elongation. The stems of the cress gets longer, the leaves sparser, all in an effort by the plant to grow away from the shadow. As the cress elongates, the body of the artist shrinks under the strain of remaining in a state of “vegetalized” immobility.

As Petrič explains:

My goal during the artistic research is to explore the possible biosemiotic cross-section of humans and plants at various levels of organization, challenging the prospect of intercognition – a process during which the plant and the human exchange physico-chemical signals and hence perturb each other’s state. Attention is brought to the materiality of the relation, which results in a perceptible manifestation, a change that can be observed in both partners of the exchange.

Petrič has previously worked with her own body, with rats and with mussels. Some of these works have been regarded as controversial because of the way she was ‘instrumentalizing’ animals. No one, however, objected to her using plants in an art project.

While exploring the possibility of establishing a connection with plants, the artist brings to light the difficulty for the human sensorial apparatus to fully comprehend the complexity of vegetal communities. If we can’t empathize with plants, how can we claim that we know them? How can we be comfortable with the idea that they are excluded from contemporary ethical discourses?

Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, Be-wildering performance. Photo: Bas de Brouwer

Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, Be-wildering performance. Photo: Bas de Brouwer

Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet, Be-wildering performance. Photo: Bas de Brouwer

Kira O’Reilly and Jennifer Willet‘s collaboration explored the possibility of “re-wilding” their art/science practices in various settings. During the performance in Amsterdam, Willet collected samples from O’Reilly’s bodily fluids and then stored them inside one of the little spheres of her frilly lab coat.

Willet intends to wear the coat for a year, without ever washing it. She plans to wear the garment both inside and outside science laboratories. Over time, the coat will accumulate micro-organisms that shouldn’t normally be introduced into science labs (or outside of them) and new eco-system will grow.

By smuggling of biomaterials across continents and settings, the work explores the rules of non-contamination between various areas (lab/outside the lab, between countries that have different rules regarding lab sterilization, etc), the spread of invasive species, the difficulty of creating true wilderness, etc.

Previously: Trust Me I’m an Artist. Ethics surrounding art & science collaborations (part 1) and Inheritance, a precious heirloom made of gold and radioactive stones.

Trust Me, I’m an Artist is curated by Anna Dumitriu and Lucas Evers along with project partners Nicola Triscott, Louise Emma Whiteley, Jurij Krpan. Trust Me, I’m an Artist was exhibited at Zone2Source’s Het Glazen Huis in the Amstelpark in Amsterdam and closed on the 25th of June.

To know more about the performances, don’t miss the podcasts in which art critic Annick Bureaud discusses with the artists: Taste of Flesh / Bite Me I’m Yours, as Seen by the Artist, Meeting with Martin O’Brien and Confronting Vegetal Otherness: Skotopoiesis, as Seen by the Artist, meeting with Špela Petrič.

The Waag Society has a flickr set of the exhibition and of the Be-wildering performance. I also uploaded a few images online.

The project Trust Me I’m an Artist: Towards an Ethics of Art/Science Collaboration was set up by artist Anna Dumitriu and Professor of Clinical and Biomedical Ethics Bobbie Farsides in collaboration with Waag Society and Leiden University.