Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Corporations and other large firms, especially U.S. ones, routinely send their employees on team-building survival courses. Most of these one or two-day experiences teach participants how to light a fire, build a shelter, find edible plants and otherwise ‘survive in the jungle.’

For some companies, however, a survival experience is not enough. They want to see how individuals within their team can handle extreme situations, how much it takes for them to ‘hit their threshold’. That’s how white-collar workers find themselves in fake aircraft cabins, real indoor pools and inflatable raft, learning how to survive plane crashes, fires, war scenarios and other catastrophes.

Organizations that had so far instructed people working for the police, the army or security firms are now adapting their equipment, training and simulations to coach these new, usually desk-bound workers.

A preliminary exercise in learning to escape from a submerged cockpit. Credit George Etheredge for The New York Times

When Olivier Peyricot, Scientific Director of the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne, invited Ilona Gaynor to reflect on the main theme of the biennale, work, its shifting paradigms and future, she didn’t come up with an object, didn’t propose any near-future scenario nor speculated on the impact that AI, 3D printing or climate change will have on jobs.

Instead, she found inspiration in an article about plane crash simulation for office employees, reflected on the dynamics of social mobility, wrote a 4 act play and designed a set for a theater performance that might never take place.

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

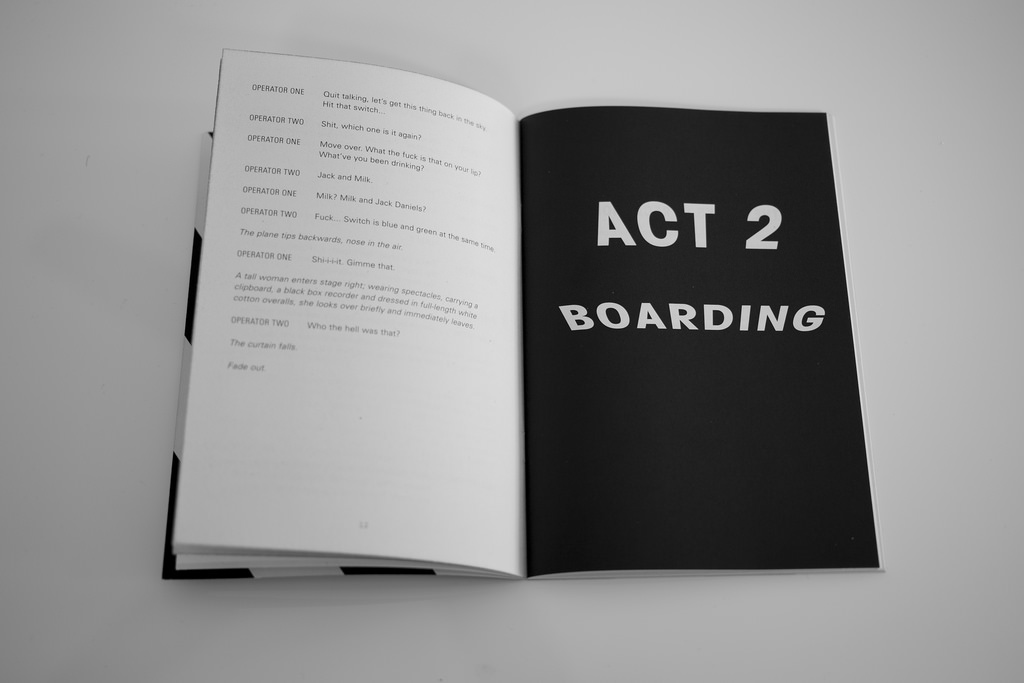

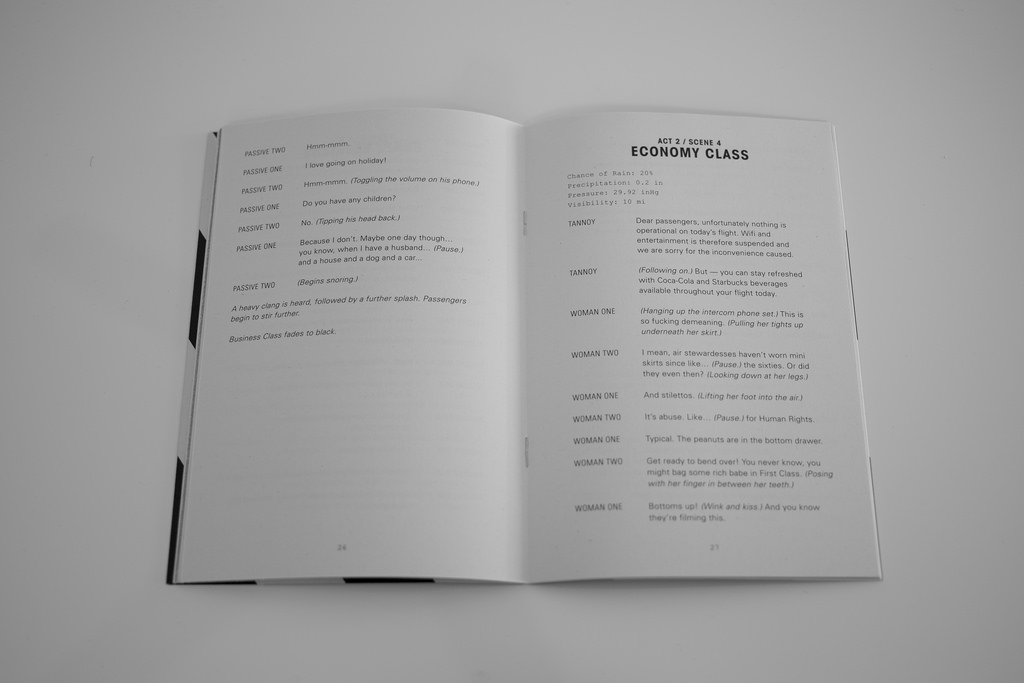

The play is called The Ascent. It centers around a law firm that goes on a morale boosting training day. The exercise takes place inside a plane designed specifically to simulate a plane crash and teach people how to escape the mayhem that ensues. However, there’s a (real) technical problem and things quickly get out of hands inside the fake plane. Everything goes terribly terribly wrong for the characters of this fiction inside a fiction. Not that you care for any of them. They are rude, catty and supremely unpleasant.

In their daily life, these people scramble for a promotion. On the plane, they compete as ruthlessly for sheer survival.

The Ascent is an intriguing parable about the ecosystems of power, about people who have lost any illusion they might have had about their job but still fight for it, even if that means hitting their colleagues below the belt or submitting themselves to some inane team-building activity.

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

The work attempts to examine the discrete nature of class politics; paralleling contemporary workplace geometries from multiple vantage points; subtly questioning the assumption that all progress in life or in the workplace is purely vertical. It’s as much about finding escape routes as it is about ‘climbing a ladder’.

I asked Ilona Gaynor to tell us more about her participation to the Design Biennale in Saint-Etienne:

Hi Ilona! The Ascent seems to push the boundaries of design, the discipline itself but also the way it is exhibited and experienced. Visually, the work is very seductive but to experience it, the visitors have to properly sit down, read the full play, imagine the protagonists, perform the interactions in his or her head and form their own conclusions and associations with what work culture means to them. Why did you choose a setting that resists so many of the usual codes of design and design exhibitions?

It was a commission from Olivier Peyricot for the 10th edition of the St Etienne Biennale and it seemed somewhat important for him that the constraints of the previous editions be addressed, in wanting to make it a more conceptually challenging design exhibition. As opposed to somewhere like the Milan, Salone del Mobile – which is very market oriented and relies heavily on expensive spectacle and brand association. Olivier asked a team of writers, curators and researchers from backgrounds in philosophy and art criticism (rather than designers) to search for writers, artists and designers that worked in contrary to this and I suppose this was myself, amongst others.

Designers for a while now have been describing their work as “narrative” or “fiction” without really pertaining to what that might entail and how to utilize fiction within design as tool for exploring language, sequence, chronologies and so on (and of course there are exceptions.) But it’s become a fairly benign turn of phrase: ‘design fiction’, ‘fiction futures’, ‘speculative fictions’, ‘virtual fictions’ and so on; for the justification of making work that needn’t exist or be imagined within the critical constraints, complexities or nuances of our reality. It’s become a confusing and lost space that has somehow separated itself too far apart from both: its original critical intent and the opposite end of the spectrum; in so much that I wonder where the motivations for making all this work lies… I’m fairly certain that it no longer lies in the nature of criticism, but elsewhere… design has begun to reposition itself as a sort of stubbed, depoliticized science fiction; rather than shaping and regulating the contemporary critical imagination.

As such I wanted to stay away from the conventions of design; particularly speculative design. The Ascent is an experiment. Whilst I’m not suggesting at all that this work comes close to resolving my own thoughts about the broader issues of design… it is an attempt to relate design, language and image in a way that is more than simply suggestive of fiction, but a written work of fiction. An affirmed allegory; grounded in its criticism (in its most traditional semantic sense) that examines a particular aspect of the contemporary working condition – presented as a four act play and its accompanying set. It was also important for me to exhibit something that wasn’t burdened with the reliance of an object as its only voice with which to speak.

So I wrote a play that uses design to reinforce its spatial and political narrative; as opposed to the reverse.

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

How do you manage to make visitors of the biennale engage with a theater play that is never performed?

I’ve always thought the magic of an experience was in never experiencing it. In that designing and writing in anticipation was far more interesting, more imaginative somehow… I loved the book designed by M/M Paris Napoleon: The Greatest Movie Never Made. It’s a curated collection of the research materials for Kubrick’s unrealised film Napoleon. A pantheon of a project in that it was all the preparatory material for a film that would only ever come to exist as a dense collection pre-production notes. Depicted through: 15,000 locations that were scouted and documented, Napoleonic images, sketches, architectural drawings, costumes, typographic title studies and dialogues between film studios and historians. It’s a beautiful collection of research materials that I imagine would have been disappointing if eventually realized, in contrast to the vast and acute details of his proposal. I often think that most events and films were probably more imaginative and compelling on paper then in their final realization.

In contrary to this, it would have been very difficult to keep up a performance of longevity throughout the course of an exhibition with thousands of visitors. It was hard to tell how many engaged with the work… and it’s never been something that’s really concerned me; but it is a question that always comes up and I think it’s a question that’s highly unique to design. But my primary attempt to engage with the audience was in the design of the set itself. Minimal in its geometry; the planes structure is formed in tubular steel and designed to be a reduced three dimensional line drawing, that could be seen in plan section from above as printed in the play manuscript. The structure; rendered in white; details the fuselage, wing span, tail fin and pointed nose of the cockpit. The interior is divided into four sections: First Class, Business Class, Economy Class and Pilots Quarters and in each of these sections sits rows of folding chairs that are proportionally spaced in correspondence to the class they are located in; some having more leg room then others. As written in the play, the characters are separated amongst the three class sections according to their position within the law firm they all work at: junior staff, administrative and secretarial staff were sat in economy, the partners in first class and the senior staff within business class. Positioned on selected back rests of the seats are signs labelling character seat assignments; freezing them in position for the audience to imagine them sitting in position; undisturbed after boarding.

Insert United Airlines joke here

I chose the location of a plane for The Ascent for a variety of reasons… but one aspect that was particularly important is the pre-existing connotations that relate to class and the tensions that surface when thinking about air travel.

The visual and spatial divide of wealth, status and political standing that occurs within such an acute space is always really striking to me upon boarding. Of course, the ironic overbearance being that if it were to crash, we’d probably all die just as equally. In act four however; entitled “Dying,” the plane tips backwards, submerging economy class in water, forcing the passengers to ascend; climbing up the seats to reach first class – which ultimately sets on fire. Those whom have managed survive that sequence of disasters, are either forcibly drowned by other co-workers (other lawyers) or are electrocuted when a powerline falls into the water.

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. Exhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

If you had the money, would you consider having it performed? or turned into a video?

There will be several readings of it with each of the characters being read by actors, separate from the set. But no performance in any kind of a spatial way, although I’d certainly change my mind if the appropriate opportunity presented itself.

The work evokes a TV series (you mention House of Cards for example in your essay) and also Hollywood disaster movies. So why did you choose to communicate your idea through a theatre play?

Historically, theatre existed as a political tool to enhance the popularity of leaders needing support. Funded by the rich and powerful through taxation; with the hopes that the success of the plays they had sponsored would provide them with a way into politics. But it soon evolved… becoming a medium with which to critically investigate the world they lived in and what it meant to be human through three strands of dramatization: comedy, tragedy and satyr. I chose theatre, rather than television as a way to refer back to these traditions of political theatre; whereby the subjects of contention were always class related and often dealt with ideas of labor, abuse of power and man’s relationship with the gods.

When I think of “work” I’m immediately drawn into an aesthetic of air conditioned office spaces, with shitty stained carpets and suffocating plants gasping for fresh air; amongst the smell of cheap percolated coffee and the sound of photocopiers. It’s a rich behavioral and acutely aesthetic environment; rife with cynicism. I’ve been captivated by it for years and was something I was keen to take a closer look at. I love the original British TV series The Office (2001) and Chris Morris’s Jam (2000) and I somehow wanted to captivate and exaggerate the criticisms that could be drawn out through amplifying what might happen in the event of putting a clash of archetypes in a pressured, but perilous environment or situation.

The play is set on an airplane simulator that is used as a training environment for coping with extreme scenario situations. These types of simulation experiences are used by organisations; such as investment banking and law firms as away-day experiences for training their staff; the implied implication being that it would improve team work under pressure and a boost staff morale. I came across this phenomenon upon reading an article published in the New York Times titled “Need a better morale boost in the workplace? Simulate a plane crash.” It was a title I imagined would have been read aloud by a character from Beetlejuice. The article detailed the nature of simulating plane crashes, whereby the fuselage crashes into water and you and your colleagues are all trapped under water and must escape before drowning. There’s a lovely quote that reads “There are specific types of groups that like high-risk activities,” he said, citing lawyers and people in sales, public relations or marketing. Those in social work, nursing, finance or engineering, he said, might not be as keen to face the fear of drowning.” Quite simply I thought that this was it… this is enough material here to shape a comedy; a unique situation that would escalate the typical work place tensions in a pressured environment; where politics, bias, life and death was all conflated to margins of time.

Trainees brace before entering the water in the simulator. Credit George Etheredge for The New York Times

Students help one another board an inflatable raft. Credit George Etheredge for The New York Times

Participants learn to swim as a group. Credit George Etheredge for The New York Times

The Ascent is part of a biennale that explores the work practices of the future. Your vision on the theme is bleak. The employees of the company are rude and selfish, there is still a lot of sexism, the plane staff advertise coca cola and starbucks as the only way to appease nervous passengers, etc. Does this scenario echo the direction that work culture is taking?

I think I was the only designer that didn’t position my work within the future. I never do; optimists belong in the future and I’m certainly not an optimist. We already live in a dystopia and any attempt to imagine it in the future would be a facile endeavor somehow. As such I imagine (the western and middle class) working environment is already this way… although, much subtler in its ruthlessness. I’m not sure my framing is all that bleak but rather an outwardly cynical view. The play was actually written as a black comedy and I was told when it was translated into French became a much, much darker read.

The characters were highly exaggerated, so much so that they were written as paired archetypes; notated as (One and Two) that were designed to reflect one another’s selfish, uncompromising and draconian nature. As previously mentioned all the characters were organised and positioned by class within the corresponding sections of the plane. Among them: The Pricks are located in First Class, The Passives in Business Class and The Nobodies and numbered seats were located in Economy Class. Female characters have no personal identification and were simply labeled as Woman One and Two. I felt it was important to heighten the sexist and abusive nature directed at the female characters, whilst at the same time making light of it…

The essay “Our Attempts to Ascend. Escape Routes and Cosmic Trapdoors” was written for the exhibition catalogue and puts forth a repositioning of the current definitions of work, as a form of contemporary escapology. A spatial practice that is navigated between those that move horizontally– adopting moves, conflicts and entanglements; as a reckoning material force with which to escape their shrinking space, whilst afterwards recover their expansiveness (the Frank Underwoods). And those that attempt to move vertically– but either through mental exhaustion and exploitation; fail to fully discern the required amount of complexity in relations, impulses and directives… resulting in compelled attempts to escape in an effort to save themselves, rather than being able to successfully maneuver.

The Ascent attempts to reflect a moment in time, when these two definitions collide.

Ilona Gaynor, The Ascent. EExhibition view at the International Biennial of Design in Saint Etienne. Photo: Ilona Gaynor

Thanks Ilona!