Many artists and activists have worked on projects that denounce the loss of privacy online. Very few, however, have put their social, financial and mental well-being at risk in order to expose the damages of a carefree attitude towards our own digital footprint.

Mark Farid, Seeing I, ongoing. Photograph by Sophie le Roux

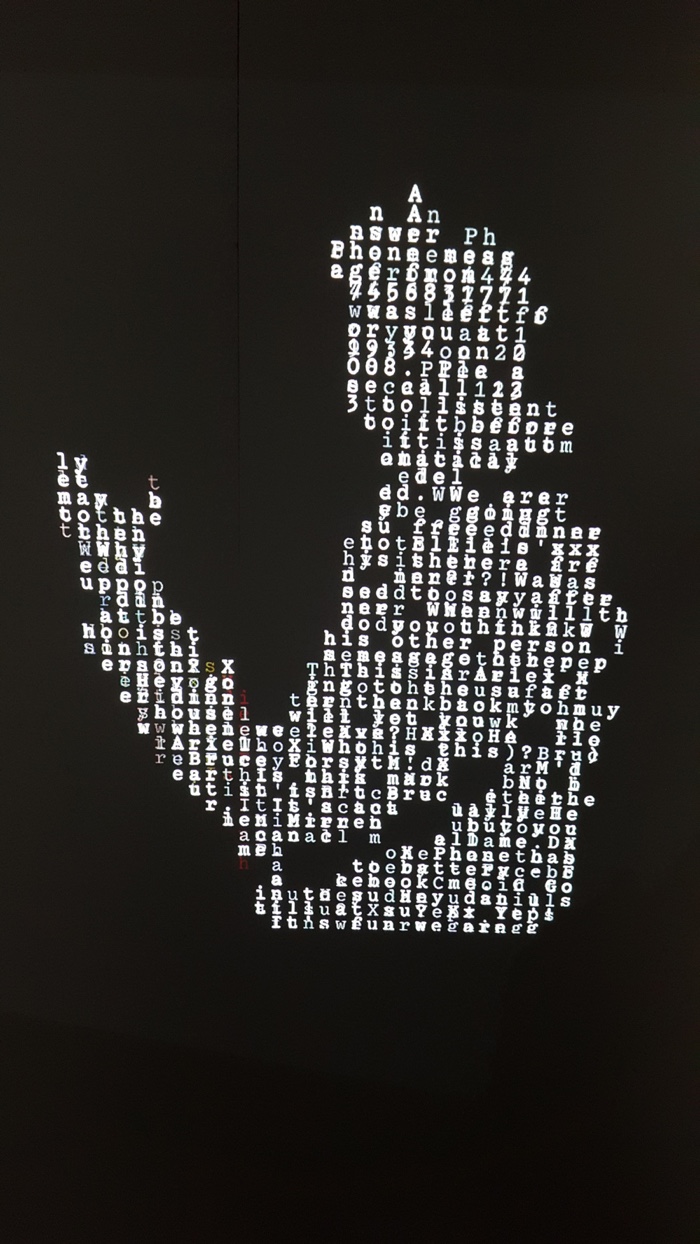

Mark Farid, Data Shadow, 2015

But Mark Farid did just that! Deeply convinced that “online privacy is the only right we have left”, the artist decided to give away his entire digital identity to anyone who’d want it. Back in 2015, he participated to a panel discussion entitled “Data Shadow: Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed” in Cambridge. After a presentation of his practice, Farid surprised the audience by displaying a document listing the login details of all his online accounts and inviting everyone to use them as they pleased. Within minutes, people he didn’t know had changed most of his passwords, from his online banking account to his Apple ID. The accounts were no longer his.

From that moment on, he embarked on a painful adventure: he lived with no digital footprint for 6 months, using multiple pay as you go phones, paying everything in cash, scrambling his IP addresses, etc. The experience was not only costly but it also made his social life ridiculously complicated.

After an experiment that suggested that Farid had something to hide, the artist went back to normal modern life, the one in which most of the exciting things you do is online and promptly turned into sets of data that both governments and corporations can snoop on.

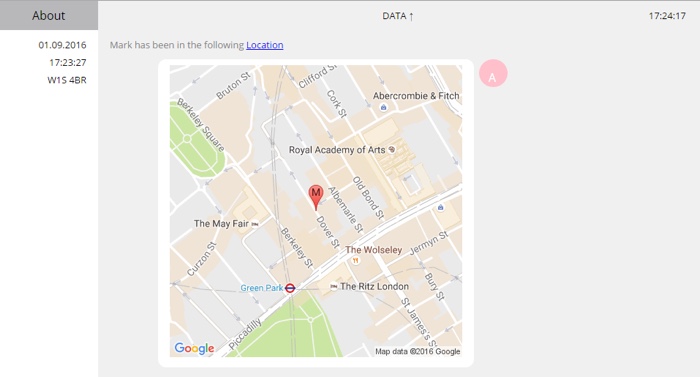

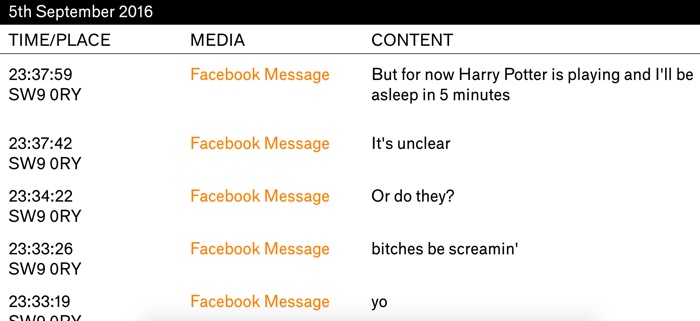

Then came September 2016 when the artist decided time had come to further destroy his online privacy and demonstrate that he had nothing to hide. For a full month, he live streamed his digital footprint. The performance, titled Poisonous Antidote, involved exposing online and in a gallery in London all of his personal and professional emails, all his text messages, phone calls, Facebook Messenger, web browsing, Skype conversations, locations, Twitter and Instagram posts, as well as any photographs and videos. The work disclosed his interactions and daily life but it also questioned the assumption that you can fully comprehend a person through only their digital footprint.

Mark Farid, Data Shadow, 2015

I discovered Farid’s work at the Strasbourg Biennale of Contemporary Art, the first edition of an event that invites us to reflect on what it means to be a citizen in the age of hyper-connectivity. The biennale remains open until 3 March. I’d recommend you swing by the charming city to see the exhibition if you’re in the neighbourhood. If not, here’s a transcript of a conversation i had with Farid after i met him in Strasbourg. We talked about the density of our digital footprints, the mental pain of spending months off the digital grid, and his plan to spend 28 days wearing a VR headset to experience the life of another person.

Mark Farid, Poisonous Antidote exhibited at Gazelli Art House in 2016

Hi Mark! Recently, while I was recently visiting the Strasbourg Biennale, i saw the premiere of Poisonous Antidote, a film that you made in collaboration with film-maker Sophie le Roux to reflect on the whole performance. The press kit of the biennale mentions “there was no restriction on the content publicised”. But surely you did censor yourself sometimes, didn’t you?

So were there any self-restrictions?

There was absolutely a degree of self-censorship, and equally, there was absolutely an – arguably greater degree – of performing at the same time.

Poisonous Antidote had two sides to it for me, the first was for the audience: just how intimately you are able to comprehend a person – their humour, temperament and rationale – through only their digital footprint. When you listen to my phone calls with my dad, read my test messages with a girl I was seeing at the time, see what I was searching and where I have been going – very quickly, you really do start to get a very good idea of who I am.

The other side of it was more personal, it was for me to see to what degree knowing that everything I was doing was digitally documented forced me to see, and judge myself objectively. This of course resulted in self-censorship – limiting what I would search, what I would say to people, and most – how I would interact with people. I wouldn’t lose my temper, for example, except for once, at my dad, which is in the film.

It also resulted in ‘performing’ – I went on holiday with my dad for the first time in seven years during that month. I visited Leicester, where my parents live, three times that month, when normally I go back home once every three months. It also meant that I was going to lots of museums and galleries, going on walks and reading a broad range of things online instead of predominantly reading about football; I was trying to look like an interesting cool artist who does what a cultured artist should do.

Contrary to what I was expecting to do – which was to limit what i was doing – the performance actually opened up, and essentially forced me to do these activities, which I otherwise probably wouldn’t have done to the same degree, or at all.

Mark Farid, Poisonous Antidote exhibited at Gazelli Art House in 2016

Mark Farid, Poisonous Antidote exhibited at Gazelli Art House in 2016

Do you have any idea about the type of people who were watching the performance? Were they mostly friends who checked the website to support you? Or were they mostly complete strangers?

There was just over 32,000 views on the website during September 2016. The views have been from around the world but predominately came from Russia, USA and the UK. And obviously as well at Gazelli Art House, London, the gallery which funded and exhibited the project.

To date now, there have been 47,000 views on the website.

How about your friends and family? Did you make them aware that any interaction with you was being streamed online, for anyone to hear or read?

On the first day Poisonous Antidote started, I sent a message to all my contact (on my phone) to inform them that everything for the next month would be broadcast: emails, text messages, Facebook messenger, WhatsApp, and phone calls would be published online, in real-time, on www.poisonous-antidote.com. Pretty much every time I was on the phone I would inform them at the beginning that the conversation was being broadcast, and if people started getting slightly too intimate with me, then I would also remind them of the situation.

There were three people who did had an issue with this and refused to talk to me for that month. But to my surprise, only three people! But many of my friends liked it and some had a bit of fun with it and started trolling me which annoyed me a little bit at the beginning, but I would have done exactly the same thing!

I’m curious about the people who didn’t want to engage at all with you during that month? Were they a bit older, from a generation generally viewed as being more protective of their privacy?

No, they were in their 20s and 30s. There was also the Director of arebyte Gallery in London who wasn’t too happy with our conversations being broadcast. Funnily, he’s one of the first phone calls in the film. The last one too. He didn’t like it but ultimately he had no choice but to get in contact with me as they’re funding my next project, Seeing I. But it nicely highlights that even if you want privacy, and you were to do everything within your means to ensure your privacy (he does not), other people’s indifference to data privacy will ultimately be your demise.

But really, most people didn’t care. And that’s something I see elsewhere in my work, which until very recently I was finding to be very surprising.

Mark Farid, Data Shadow, 2015

Mark Farid, Data Shadow, 2015

Poisonous Antidote was the third and final part of a series of projects, wasn’t it? Can you tell me more about the other parts?

To coincide with the first draft of the Investigatory Powers Bill (Nov 2015), the first part of this three part series was Data Shadow (2015) which was an interactive art installation commissioned by Collusion, in partnership with Arts Council England, the University of Cambridge and The Technology Partnership. Located in All Saints Gardens, Cambridge, all visitors were required to interact independently with the installation, entering one at a time. On entering the 8 x 2m shipping container, the participant was greeted by a woman holding a contract of consent. Until signed, the woman remained silent, directly staring the individual in the eyes (a physical manifestation of Terms & Conditions). Once signed, candidates proceeded to join the WiFi. Participants progressed to the second half of the container, divided by a partitioning door. With sensors tracking the participant’s movements, their real-time (digital) shadow was cast by a projection on two facing walls – one filled with 1000 characters from their most recent text or WhatsApp messages, the other a collage of 64 images from the participant’s mobile phone. On opening the exit door of the shipping container, all information Data Shadow had on the individual was automatically deleted, ready for the next participant to proceed.

To my surprise, the overwhelming majority of people were not annoyed, scared, or bewildered by it, at all?! There was an 18 year old girl who told me it was “so cool” that I had managed to expose the naked pictures of herself and her boyfriend on her phone.

The second part of this series was the accompanying talk to Data Shadow at St John’s College, University of Cambridge, in which I shared the login details to my entire digital life with the audience, inviting them to take, use, share and change the passwords to my accounts as they please, which ranged from my Facebook account, Apple ID, to online banking, whilst I attempted to live without a digital footprint for 6 months. If you want to know more about both of these projects, please watch my TEDx talk.

And then obviously Poisonous Antidote, the exhibition and online in 2016, and then the film in 2018, were the final parts of this series.

Mark Farid, Data Privacy: Good or Bad? at TEDxWarwick

There are many discussions about the need to value privacy as a protected right. Yet, I often feel that most people do not really care. Do you think that this is due to people not realising what a loss of privacy entails or is it simply that we have new definitions and forms of privacy?

Personally I think it’s because no one is giving a satisfactory response to the statement, “I have nothing to hide”. I put a lot of blame on this statement, as it really angers me. Mainly, because it’s not true – everyone has something to hide, but more so, because I doubt that everyone, on their own, universally came up with this statement, so they’re simply regurgitating an incorrect statement, that shuts down the conversation. Why it shuts down the conversation, is because, the phrase “I have nothing to hide” is based on a presumption that we are guilty until proven innocent. This question flips the subject, quietly, but firmly putting the onus on you to explain why you have nothing to hide. It suggests that you are guilty until proven innocent and this fundamentally goes against innocent until proven guilty. But as I say, I don’t necessarily blame the people making this statement, I blame others – myself included – for not being able to give a good, snappy one-liner response to this.

To come back a bit more to your question, on people not caring about data privacy, I had always ultimately assumed it would take a huge public breach of data privacy before people changed their view. And then Cambridge Analytica happened and I thought that would have played that role of offering a counter-response by showing what happens when private data is used politically and in the wrong way. However, it still hasn’t brought any real results – legally, socially and culturally – in fact, it is Mark Zucckerberg and Facebook who are suggesting the regulation that should be imposed on them! Truly Crazy!

I feel where work like mine has missed the point, is that think people need to be confronted with their data in front of loved ones, but then this becomes too unethical, and this is the problem, data misusage is hugely unethical, and to really highlight it, I think you must be equally, if not more, unethical.

Still, i feel that we’ve reached a point i find a bit unpleasant. I was recently at the Chaos Communication Congress in Leipzig and that’s probably the only conference i attend nowadays where they tell you specifically that if you want to take a photo of the audience you have to ask people for their permission to be photographed first. Everywhere else, people do as they please and you end up finding photos of yourself drinking wine and making stupid faces on strangers’ Instagram accounts…

Speaking of the top of my head, this is touching upon two truths, I think.

First there’s the idea that in a free, neo-liberal world, the individual is at the centre: the individual is free to do as they pleases; asking for permission to take a photo of someone, in a public space, can be seen to be a restriction of the individuals (the photographers) liberty (to do whatever they want wherever they are). Obviously this is a slightly warped take on neo-liberalism as we’re talking about taking photos of people, but I think this is one of the roots of what enabled the normalisation of people to take photos of whatever they want. Of course then there is the uploading of the photos on the world wide web, but extremely rarely do people stumble across photos of themselves taken by strangers. But I think this has a bigger foundation in what the world wide web used to be, something free, open and for the people. Back in the day, pre-Facebook, when Google was simply a search engine, when Amazon was a bookshop, ideas of the internet, and even filming and taking photos in public spaces was completely different. But now, as the world wide web becomes more and more centralised, monopolised, and a capitalist Utopia – totally privately owned, essentially unregulated by governments, with a facade of being uncensored, free and democratic – we are the commodity and our data is the currency. This changes everything.

This leads us nicely into the second truth, which I think is a development of the centralisation of the world wide web. Facebook, Google and other privately owned online companies want your data, and want to know everything about you. Not you specifically, but you within the collective. Governments are quietly happy with this, for obvious reasons, along with the monopolisation (of the world wide web by Google and Facebook) as it’s hugely expensive and time consuming to get warrants to demand that lots of different companies must handover data. Getting two warrants, and forcing those two companies to do so is much easier and quicker than getting 20, for example. And then once they do get the data, getting it from one or two companies means they don’t have to process, organise or most importantly analyse your data themselves to nearly the same degree. If your data is coming from 20 different companies, that all use different formatting and (code) languages, then you have to change languages, and format, then aggregate and process this, and so on, which is very expensive and time consuming.

It’s significantly cheaper and efficient for Governments, advertisers, or anyone for that matter, to have one or two companies having all of your data.

And then of course when Google, Facebook, and the Government are ultimately in favour of a very similar, particular model, a subtle and continuous message from these companies and institutions will have underlying messages pushing the came philosophy – that data privacy doesn’t matter, or, ‘I have nothing to hide’. Overtime, this subtle message becomes engrained, and when you combine these incredibly powerful and influential companies (and Governments) you start to realise just how hard it is to argue, and succeed, in the fight for data privacy.

Coming back to your performance, i must say i found it very shocking, even though there is a long tradition of artists exposing their private life in the most open way (people like Tehching Hsieh, Marina Abramovic, Yoko Ono, etc.) I should be immune to a work like Poisonous Antidote but i’m not.

How has this one month performance changed the way you view social media and digital technology in general? Did it change the way you are using it?

Interestingly, Poisonous Antidote was actually the thing that got me to start using social media again. It really was my Poisonous Antidote. I’m not too sure about the title of the project, but it is a fitting one for my personal experience. As I mentioned earlier, when Data Shadow was being exhibited, and I gave the accompanying talk titled, Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed, I gave away the passwords to my entire online life, from my Facebook account, to my Apple ID, to my online banking account login details, and everything in between. This included my social media accounts: Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. That was in October 2015. Poisonous Antidote was September 2016. So for that period I didn’t have any account.

It was only halfway through September 2016 that I I started to use (new) social media accounts, and this was to see the difference without social media and with social media and how that would change the whole experience to me…

What!??! You didn’t have any social media account for such a long time?!

No, when I gave away my login details, people pretty much immediately changed the passwords to my accounts, and that was that. They were gone and I had no way of get them back. Someone had been using my Facebook account for quite awhile, with some friends getting messages from whoever had the account. Someone is still using my old Twitter account (@markfarid). They set it private and occasionally tweet at me which is both frustrating and fun. It’s worth noting that I didn’t have any kind of accounts for this period – social media to an Apple ID to a smart phone. In any case (and ironically) Poisonous Antidote – a fight for data privacy – made me go back to social media.

But yes, it changed the way I use social media, a bit, but social media – and most website – are quite limited in what you’re really able to do. And as was the case with the gallery director of arebyte Gallery (in the Poisonous Antidote film), other people significantly reduce all of your efforts.

Do you do anything specifically different?

I’m very clear about the way I interact with everything and treat it as if it were a public conversation. So for example, the way that UK is moving at the moment, regrettably I won’t be surprised if we, by necessity, have a form of privatised healthcare in the future, and social media data, amongst others, will almost certainly be one of the things used to decide how expensive or cheap your medical insurance is. So i’m extremely cautious about the kind of things I’m saying to friends and family on Messenger, along with any photos of me, and what I’m doing in them.

I do as much as I can, within reason, the ‘headline’ thing, I guess, being that for every service that I use online, (Facebook, Twitter, Skype etc.) I have a different email address linked to it. Each email address is linked to a pay-as-you-go sim card that’s paid for in cash. Facebook is linked to one email address. Twitter is linked to another one, as is every sign-up I do. Nothing is linked together. I also use fake information, such as fake names and wrong birth dates. Ultimately, if someone wanted to link these accounts together, they could, it’ll just involve a bit more legwork for whoever is doing it.

How many email addresses do you have?!

Haha, I’m not sure. Many many dozens.

But then it makes you look suspicious.

I guess so, but the idea of ‘Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed’ was that by various strangers using my old, but real Facebook account, Twitter account, JustEat, Quora, etc. there shouldn’t appear to be anything suspicious, as they’re being used. That’s the reason why i gave away my passwords, because you’re not able to delete your accounts, so giving away my passwords was the only way I could essentially think of to make the accounts redundant and make the data useless, and at the same time, become invisible, for use of a better word.

How did ‘Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed’ go? How long were you doing it?

‘Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed’ was from October 2015 to April 2016.

When i gave away my passwords in October, the plan was to live for six months without a phone or computer. About 3 weeks after the start of the project, the Paris attacks happened which changed everything. For me, the Paris attach was the 9/11 of Europe. That was the big moment when terrorism became really present in Europe – innocent people being shot in restaurants, concerts and on the streets. The political and social landscape changed overnight. The argument for data privacy, fell flat on its face. The argument for data privacy is built upon individuality and the option to not conform, which is hugely outweighed when confronted with life and death.

During this 6 month period, without a phone or computer, my financial life plummeted beyond all belief. Along with my social life. To talk to me, people had to travel across London and knock on my door and hope I was in.

At one point, my dad hadn’t heard from me for a few months and was incredibly worried. He drove three hours to London to see if I was alive. I returned home to my flat to see a hugely worried, angry, but relieved parent.

At this point, I ‘decided’ I would get a different phone each month and would give the number of that phone to 5 people each month, and it would be a different 5 people every month – to made it harder to link it to me, i.e. If you had my phone number one month, you wouldn’t get my new one the next month, and this included my parents. Due to a plummeting financial side, and a lack of work coming in, I also got 3 different computers, each one I would only use for very specific purposes, at very specific locations, at specific times, whilst using a VPN and Tor.

What i found most traumatic in this experience wasn’t the horrific financial struggles, nor the lack of a social life. Not even the fact that someone committed fraud against me during this time and totally destroyed my credit rating – to the point that I was rejected from a new phone contract last year. All of these things were bad but manageable.

The hardest thing, however, was the cultural vacuum that I lived in during this period. Each day, I was getting more and more disconnected from the ‘real’ world, and what I found was that, slowly, this was effecting how I was interacting with people, what we would interact about, and my overall confidence. For example, it took me over 24 hours to find out about the Paris attacks, but if you were on Facebook – which I had no access to – things were going crazy, you couldn’t not know about it, but in the physical world, people were barely, if at all, talking about it.

I absolutely became depressed and developed quite a serious dependency on drugs a few months into this, and I became a hermit in many ways. In a very simplistic way, one drug replaced another. It wasn’t sustainable – although I did do the 6 months, it was truly awful. Having privacy to allow my sense of self to be free is not what I thought it would be.

I’d recommend watching my TEDx talk, if you want to know more about ‘Anonymity is our only right and that is why it must be destroyed’ and Poisonous Antidote.

So Poisonous Antidote followed this in September 2016?

Poisonous Antidote was my flip back because I found that the exact opposite happened: in totally giving up privacy, by having external-internal, expectations placed upon myself, I was infinitely happier. But this is the problem – my projected self, a constructed image of who I want to be, had a dedicate place to exist, and in doing so, it placed my virtual self at the centre of my real-world experiences.

For the first fifteen days, I found my usage of phone and laptop were normal. If I consciously acknowledged a change, it was, if anything, that I gained in confidence – using the experience opportunely to send things I might otherwise have not. But on September 15, half way through the project, I made a Facebook and a Twitter account, and almost immediately I became aware, even anxious even, about some of my prior arrogance.

Progressively more changes occurred. When I woke up, my phone and computer were not the first things I looked at, as I didn’t want people to know what time I woke up. When I did eventually go on the Internet, check my emails or reply to messages, the first things I looked at was the news, not the Leicester Mercury to read about football. When I was working, I didn’t procrastinate – digitally anyway, because everyone could see. I became very aware of my locations, so I made sure that I was going out, that I was being sociable, and that people could see I was being productive with my time. I would speak to my family more, I was on the Internet less, I was more productive, and surprisingly to me, I was enjoying myself more.

Mark Farid, Poisonous Antidote, 2016. Film by Sophie le Roux

Mark Farid, Poisonous Antidote, 2016

This is very different from ‘Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed’…

Poisonous Antidode certainly highlighted my own online editorial habits, the density of our digital footprints and, for me, the necessity of privacy. Unlike ‘Anonymity is our only right, and that is why it must be destroyed’, where I gave up online privacy to gain personal privacy, only to realise social media is indispensable to contemporary life, Poisonous Antidote embraced the publicity of social media. Subsequently, I have found that I was consciously and subconsciously changing my actions and behaviour to ensure I conformed to my insecurities, rooted in society’s ideologies – that I was doing what I was “meant” to be doing and feeling validated by the knowledge people could see this.

My narcissistic thirst for approval led me to willingly relinquish privacy in exchange for a perceived social stardom, where I was constantly judging my actions and options through the potential reception of my newsfeed, assessing my and their adherence to a standardised code of conduct allowing a form of acknowledgment that confirmed my actions and behaviours. The validation Poisonous Antidote created could only be fulfilled by further consumption, and as we used it more, each post, action and interaction meant less, for I become more reliant on it to fill the growing void it created. It become a self-feeding machine.

Now of course, publishing every part of my online activity might appear to represent some dystopian future. But the truth is that most of us are doing exactly this right now, – albeit in a more limited way. We are constantly self-publishing the details of our lives to technology companies, to governments, and to our networks on social media. The difference between you and I is of degree, not kind.

I also recommend going on www.poisonous-antidote.com where you can see all of my data for the month. It has been hacked multiple times, but all of the data should be back on there. You can also see the Poisonous Antidote film which premiered at the Strasbourg Biennale, and was made in collaboration with the very talented film-maker Sophie le Roux!

Mark Farid, Seeing I, ongoing. Photograph by Sophie le Roux

Mark Farid, Seeing I, ongoing. Photograph by Sophie le Roux

And of course, i need to ask you about Seeing I which is scheduled to premiere in September 2019. For the performance you plan to experience the life of another person for 24 hours a day, for 28 days, only seeing and hearing what one person sees and hears, using VR. You had a 24 hour test. Could you tell us how it went?

The 24-hour test run was in February 2014, using a DK1 (the first Oculus development kit). It went well. Well enough to pursue the project and put it on KickStarter in November 2014, which was ultimately unsuccessful. Since then however, I have gained funding from various place and institutions and done many, many, many more trials, the longest being 92-continuous-hours.

Unsuccessful? But i saw LOTS of articles about the projects and they all suggested that you already had the money!

Indeed, this was very frustrating. The KickStarter campaign got lots of press, but the press made no mention of the KickStarter.

In the 4 and a bit years that have followed however, the project is now being commissioned by arebyte Gallery, and is in partnership with the Sundance Institute, the National Theatre, UK, Imagine Science Films and looks set to be taking place at Ars Electronica in September 2019.

We have just finished developing the headband that record a 260 degree field of view left to right and 165 degrees up and down, along with audio. This is what the other person will wear, and has been the main thing holding us back from doing Seeing I, as it doesn’t exist, until now! It has a battery life of 36 hours along with a storage for 36 hours. We will be open sourcing the code, along with the .STL file for people to 3D print after the project has taken place.

The last three sections on the pre-production side to finalise is getting Ethical Approval on the project, and finalising the funders of the documentary (directed by Petri Luukkainen), which I can’t publicly name at this time. I hope to have these two parts finalised in the next two months.

The third section is who the Other person is. If you’re interested in applying, please visit www.seeing-i.com and apply online! We favour applicants living a life aligned with the ordinary rather than the extraordinary. This means, a real-life person who thinks their life is “too boring”!

Mark Farid, Seeing I, ongoing. Photograph by Sophie le Roux

How do you prepare for this performance?

Since January 2018 I have been, and will be until the exhibition in September 2019, spending prolonged periods of time in virtual reality – a minimum of 45-hours per week – to train my eyes to function in close proximity to LCD display (with no exposure to natural light). This is also to overcome any potential motion sickness I might experience.

The longest I’ve spent in continuous virtual reality is 92-hours, as I mentioned earlier. This was the longest trial I’ve completed without taking the headset off, watching footage from a single person’s life, from first person point of view. I’ve also spent four successive days in virtual reality on three separate occasions, but these were watching stuff on Netflix, YouTube and playing games.

In June 2018, I averaged 16-hours per-day in virtual reality for 23-consecutive-days. This was a specific test, focusing on my eyesight and any potential short or long term damages that might occur. The results found no long-term damage to my eyesight, with the only short-term damage being that he was short-sighted for the two following days.

And another key part of my preparation for the isolation that I will experience during the project, where I will have no human interaction, no stimulation, and no eye contact, I have attended two 10-day silent meditation retreats and I’ll be doing another three in the build up to the 28-day exhibition.

Thanks Mark!

Touch Me, the 1st edition of the Strasbourg Biennale of Contemporary Art was curated by Yasmina Khouaidjia. The event remains open until 31 March 2019 at Hôtel des Postes in Strasbourg, France.

Previously: Strasbourg Biennale. Being a citizen in the age of hyper-connectivity.

Poisonous Antidote was commissioned by Gazelli Art House, London, and in partnership with CPH: LAB.