I’ve never been to Lisboa Soa. But a few weeks ago, I saw its founder, Raquel Castro, talk about it at Interferenze (it was amazing, I’ll write an overview of the event in the coming days.) I realised Lisboa Soa was the kind of event I’ve been looking for since the 2006 edition of the Sonambiente festival. Only sunnier and leafier.

Marco Barotti, Woodpeckers2, Lisboa Soa 2020

Sonoscopia, Fauna, Lisboa Soa 2017. Photo by Vera Marmelo

Lisboa Soa is “an itinerant and participatory sound art festival, which aims to enhance artistic creation, but also give it a social, political and ecological context through direct intervention in public space.” Born in 2016, the event has occupied several spectacular locations around the city of Lisbon: a 10-hectare garden inhabited by all sorts of volatiles, a small forest, water reservoirs, a market, palaces, etc. Each of these places presents specific spatial, acoustic or environmental characteristics that feed the sound installations and performances commissioned by the festival.

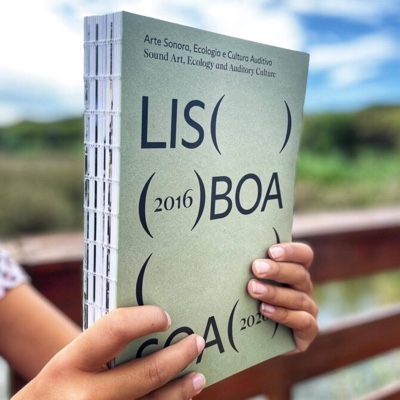

Published last year, Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 / Arte Sonora, Ecologia e cultura Auditiva. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 celebrates the first 5 years of the environmental sound art festival. Rather than a catalogue or survey of the Lisboa Soa programme, the book reflects on the festival’s ongoing investigation into the spatial, the visual but also the social and ecological dimensions of sound. The book also came at a moment when sound lovers were reflecting on the toned-down soundscape brought about by the pandemic and were wondering how education, artistic exploration and scientific research could help society deal with the ongoing, overwhelming climate and socio-political emergencies.

Published last year, Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 / Arte Sonora, Ecologia e cultura Auditiva. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 celebrates the first 5 years of the environmental sound art festival. Rather than a catalogue or survey of the Lisboa Soa programme, the book reflects on the festival’s ongoing investigation into the spatial, the visual but also the social and ecological dimensions of sound. The book also came at a moment when sound lovers were reflecting on the toned-down soundscape brought about by the pandemic and were wondering how education, artistic exploration and scientific research could help society deal with the ongoing, overwhelming climate and socio-political emergencies.

West Coast, Chilrear de Mesa, Lisboa Soa 2019. Photo by Vera Marmelo

Nuno Veiga & Yola Pinto, Uníssono, Lisboa Soa 2020

Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 is a rare gem. It is both entertaining and thought-provoking. And it contains plenty of photos, texts by artists and conversations that Raquel Castro had with sound artists, composers and researchers.

I particularly enjoyed the interview with musician and field recordist Chris Watson. A specialist in the sounds of natural history, Watson explains how organic elements without ears respond to sound or vibrations, how specific trees give forests a specific “acoustic signature” and also discusses the impact of anthropogenic noise on wildlife. I also learnt a lot from the interview with sound artist, composer and researcher Leah Barclay. Her work in aquatic ecosystems explores what sounds can reveal about the health of the environment and its rapid modification. While it was distressing to read how different species respond to the impact of anthropogenic sound or small changes in temperatures and how we are slowly silencing wildlife, her final answer contains uplifting comments on the use of eco-acoustics to better understand the environment and on the role that art can play in making urban communities connect to their environment and work towards change.

There is also a lot to ponder upon in the interview with field recordist, musician, artist and sound ecologist Peter Cusack who explains the importance of a varied soundscape, the rights and responsibilities over the sounds we produce and evokes the sounds designed specifically for Berlin’s local rail system.

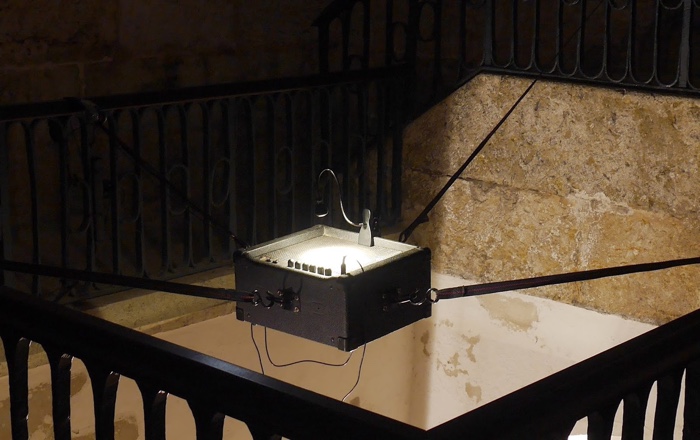

Gustavo Costa, Henrique Fernandes and Ricardo Jacinto, Phonopticon, Lisboa Soa 2016. Photo by Vera Marmelo

Fernando Mota, Concerto para una árvore, Liboa Soa 2020. Photo: Vera Marmelo

All the essays in the book offer intriguing perspectives on biophilia, the sonification of environmental problems, the acoustics of resistance and other topics but I’d like to single out Gustavo Costa’s text. The musician and co-founder of Sonoscopia reflects on the effects that the mechanisation and electrification of the world have had on soundscape, especially in cities. On the one hand, they led to the background noise amplification of human-generated sound, overlapping with and sometimes silencing natural ones. On the other, mechanisation enabled the creation of new instruments that produce new types of sounds and have a greater capacity for sound projection. He also explains how digital technology has further expanded the possibilities to produce, discover and enjoy sound just like globalisation has turned up the volume of human-generated sound. In front of the plethora of sounds, he calls for a new ethics of listening where we filter through, stop, listen, breathe and make choices about the information that reaches us. The pandemic, somehow, gave us that possibility to pause and hear some of the sounds that modernity had muffled. We suddenly felt a bit more part of the ecosystems that surround us.

Sound art, Ecology and Auditory culture. Lisboa Soa 2016-2020 was edited by Raquel Castro, a soundscape researcher, documentary director, sound art curator and the founder and director of Lisboa Soa. Get this book if you already love sound art, would like to know more about it or if you’re simply looking for new ways to experience and understand the world around you. All the texts are written in both Portuguese and English.

I found two online shops that sell it: BLX and Flur. The festival is also doing a fantastic job at archiving the performances and installations on soundcloud and on its own website. That’s actually where I borrowed some of the images below:

João Bento, Cactus in Jardim dos Catos

João Ricardo, Cactusworkestra, Lisboa Soa 2017. Photo: Vera Marmelo

Sonoscopia, Fauna, Lisboa Soa 2017. Photo: Vera Marmelo

Joan Sorrentino, Tile (Lisboa Soa edition). Photo by Vera Marmelo

Joan Sorrentino, Tile (Lisboa Soa edition), Lisboa Soa 2017. Image TWMW

Saša Spačal, Mirjan Švagelj and Anil Podgornik, Myconnect, 2013

Edu Comelles, Sínia / Noria / Azenha, 2018

Peter Cusack, Aral Sea Stories

Peter Cusack, Aral Sea Stories, Lisboa Soa 2019. Photo: Vera Marmelo

Vincent Martial and Carlos Heinrich, Ethnosphere, 2019

Kathy Hinde, Piano Migrations, at Lisboa Soa 2019

Natacha Cabellos, Laboratório para una Planta Migrante, Lisboa Soa 2019. Photo: Vera Marmelo

Natacha Cabellos, Laboratório para una Planta Migrante

Bicrophonic Research Institute. Kaffe Matthews, Lisa Hall and Federico Visi, Environmental Bikes Lab at Liboa Soa 2020

Andreas Trobollowitsch, Santa Melodica Orchestra, Lisboa Soa 2019. Photo by Vera Marmelo

Gonçalo Alegria, Coro, Lisboa Soa 2020. Photo by Vera Marmelo

Jana Winderen, at theReservatório da Mãe d’Água, Lisboa Soa 2018. Photo: José Frade/EGEAC

Raquel Castro, SOA (trailer), 2020

Related stories: Sounds From Dangerous Places: Sonic Journalism, The Manifesto of Rural Futurism, Listen to the sounds from the deepest hole ever dug into the Earth crust, Sounds from bridges, ventilation systems and other industrial spaces. An interview with Jonas Gruska, Using art to study endangered indigenous rituals and music, Walled Unwalled. The politics and violence of acoustics, Heavy Metal Detector, an interview with Steve Maher, Métaboles. On the need to decolonize nature, Recording studio for bees and other sound oddities, etc.