Sébastien Robert is an artist and researcher whose practice presents a rare combination of visual and sound art, technology, science and ethnographic research. A few years ago, he embarked on a research project called You’re no Bird of Paradise which studies indigenous music and rituals in danger of disappearing.

Sébastien Robert. © Unmmaped Films

Based on a collaborative and experimental approach, Robert’s projects attempt to translate sounds and rituals into tangible works of art that directly echo the traditions of the communities he meets.

One of his projects brought the artist to La Araucanía, a region of Chile where the rituals and alliances that Mapuche indigenous communities have woven for centuries with ecosystems are threatened by the combined impacts of climate change, land grabbing and the appropriation of natural resources. As the landscape disappears, so does Mapuche associated expertise of the living world.

Robert’s series of work The Kultrun of Cañon del Blanco studies the influence of the Kultrun – a Mapuche ceremonial drum – on the crystallisation of the Araucaria Araucana resin. The tree is not only sacred in Mapuche culture, it is also a living fossil and an endangered species. Robert’s project explores the possibilities of preserving the ancestral rhythms of the drum in the resin of the tree itself.

Mark IJzerman (visuals) & Sébastien Robert (sound), As Above, So Below, 2020

Robert also teamed up with media artist Mark IJzerman for As Above, So Below to explore La Araucanía’s changing landscape. The audiovisual performance focuses on the erosion of biodiversity and replacement of old-growth forests by water-hungry eucalyptus and pine plantations in the region which, again, happens at the expense of Mapuche communities.

Ly Mut’s Pleng Arak Ensemble, 2018. Portrait of Sum Pheng (ស៊ុំ ផេង) vocals and drum. From the series The Forgotten Melodies of Pleng Arak

Ak, 2019. © Sébastien Robert. From The Forgotten Melodies of Pleng Arak

Another of Robert’s projects investigates Pleng Arak, ancient music performed in Cambodia during shamanistic ceremonies. Traditional music is slowly disappearing due to the rise of modern medicine and to younger generations’ lack of interest in ancient spiritual beliefs. In 2018, Robert met with one of the last bands of Pleng Arak. The musicians allowed him to record their repertoire, provided that it will never be sonically shared. Because it is exclusively performed during sacred rituals, listening to this music outside of its original context would not only be inappropriate, it could potentially put the listener at risk.

The artist, therefore, translated the recording’s sonograms into a coding system based on the graphic score of one of the Pleng Arak musical instruments. These abstractions were then engraved on tablets made of limestone and sandstone and stored in the coal mine alongside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway.

I discovered Sébastien Robert’s work through SHAPE, a platform for innovative music and audiovisual art from Europe. I found the way he marries art with cultural heritage, ethnomusicology with science so moving, so ingenious that I contacted him for an interview:

Hi Sébastien! You have a background in business and economics, but you recently graduated with honours from the ArtScience (MA) at the Royal Conservatory of The Hague (KC). Most of your work now explores endangered indigenous rituals and music. How did you get to investigate that topic when your background is not in ethnography?

The first motivations behind my research ‘You’re no Bird of Paradise’ are rather personal. In 2013, following an exchange semester in Taipei (Taiwan) as part of my previous studies in business and economics, I decided to extend my stay in Asia by volunteering in Kathmandu (Nepal). There, I had the opportunity to live one week amongst the indigenous community of the Langtang valley in the Himalaya. They were all gathered in the nearby monastery of Kyanjin Gompa for a traditional festival that included hours-long mantras, war songs and yak catching. I always considered this experience as the start of my artistic practice, as this is where I took my first photographs and did my first field recordings.

Kyanjin Gompa, 2013. ©Sébastien Robert

Originally from Tibet, these people settled in this valley four hundred years ago and developed their own culture, songs and dialect, which were unique to this world. On 25 April 2015, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake shook Nepal, and a vast landslide fell on the Langtang village. An entire section of the mountainside came off, bringing with it giant boulders, much of the glacier and the frozen lake located above it. It killed almost all the inhabitants. In the space of a few seconds, the village was wiped off the map, and the whole culture of that valley vanished. Although a few young people were in Kathmandu during the earthquake and survived, they now lack the cultural knowledge of their ancestors.

That day, I realised how fragile culture and its elements could be. That is where the idea of my research ‘You’re no Bird of Paradise’ began and when I started to realise that there were more places on earth with similar risks. UNESCO even publishes a list every year called Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding which indexes music, rituals and practices currently disappearing due to technological, societal or ecological issues. It took me a few years to process this tragic event until I decided to apply to the ArtScience Master at the Royal Conservatoire (KC) of The Hague to further develop the theoretical backbone of this research and gain field experience.

I’m curious about the title of your research ‘You’re no Bird of Paradise’. Where does the name come from?

The name ‘You’re no Bird of Paradise’ is multi-layered. Originally, it comes from the titles ‘You’re No Good’ (1967) & ‘Bird Of Paradise’ (1965) from Terry Riley, one of my earliest inspirations, which appeared on an unofficial release in 2017 that I came across while laying the foundation of my research. Both tracks are some of the first plunderphonics pieces ever created – music made by taking existing audio recordings and altering them through tape loops and cut-and-splice methods to make a new composition. A technique that ‘interrogates notions of originality and identity’ to quote John Oswald, who coined the term and that I always used in my sound work.

Additionally, the Bird Of Paradise is a bird family that can be found in Indonesia and Papua New Guinea, and eastern Australia. It is a well-known bird family as most species have elaborate lek mating rituals and dances, whose images have been shown around the world, especially since hunting and habitat loss due to deforestation have reduced some species to endangered status. With that name, I wanted to highlight that when an ecosystem is disturbed, not only animal species are threatened but also indigenous communities that live harmoniously in it for thousands of years, together with their associated rituals and advanced knowledge of the natural world. Not the same attention goes to these less known rituals, yet they are as important.

Last but not least, species from this bird family are known to show off to impress other members of their community, something I encountered now and then in the art world and that I always found problematic. I wanted to contrast this by working on a profound, urgent and complex subject grounded in the reality of today and the future, with care and dedication but without being pretentious. My research goes beyond simple documentation, yet is not an ambitious ethnographic archiving project of all the current disappearing rituals around the world. Hence the name, ‘You’re no Bird of Paradise’.

Mark IJzerman (visuals) & Sébastien Robert (sound), As Above, So Below. Photo: Pieter Kers

I read in a super interesting conversation you had with Mark IJzerman that you had written a thesis about cultural appropriation in the field of sound art and how artists working with different indigenous groups position themselves. Can you tell us something about your findings and conclusions?

In the first place, I think it is important to understand how this thesis came into existence. Working on such a delicate topic naturally raises questions, starting from myself. I will always remember that overwhelming feeling I had the night before I recorded and photographed the musicians in Cambodia, wondering how I could position myself as a French artist working in a former French colony. Questions also emerged from the local communities. In Chile, the conversation I had with Milton Almonacid, a Mapuche activist, was a turning point for my research. He reproached me for overlooking the epistemological diversity of the world and extracting elements from a culture without understanding its associated values and beliefs. It took me a few weeks to process our challenging conversation, but it became clear that I needed to question my positioning, both towards the subject of my research – in the way I deal with indigenous knowledge – and towards my artistic practice – at the border of sound art, science and ethnomusicology.

Very soon, I realised that all of the information I could gather was either produced by scholars in their academic bubble analysing others’ work or coming from too politically correct publicity interviews. To avoid these pitfalls, I set myself the challenge of producing a different body of work by giving sound artists the space to express their views. It took the form of a thesis, entitled ‘Exploration or Appropriation? The position of contemporary sound artists towards Indigenous music’. One artist per continent, to present a diverse range of points of view and escape the echo chamber of largely Western artists and intellectuals talking to each other. Throughout open-ended conversations, we talked about the definition of cultural appropriation, the issue concerning re-contextualisation, the fine line between appropriation and respectful ingenuity, the different possible processes, and the expansion of the working field. Without pretending to come to definitive conclusions, I presented a landscape of positions, in which I also positioned my work and questions.

The central learning point from this thesis is that there is no one ‘correct’ way or a magical formula when working with indigenous music, instruments or communities. Every context is different, and therefore should be addressed accordingly. I would like to quote Rabih Beaini, one of the artists I talked to, who rightfully explained: “There are going to be places where you are not going to be welcome, but there are going to be places where you will be more than welcome.” The key is to be aware of your own position and awareness as an artist, and pay attention to the context and the perspective of the community the project is about. There is no way one can grasp what is going on and what will happen before going into the field.

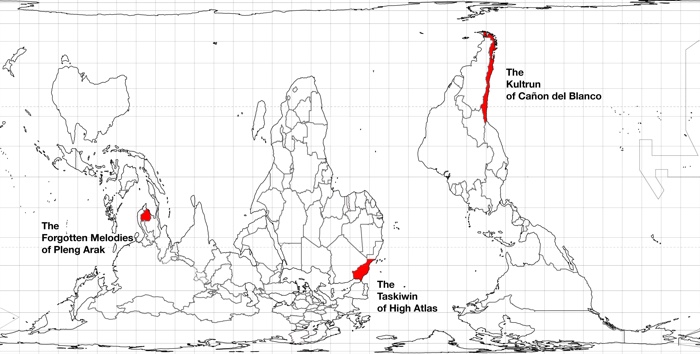

Projects: The Forgotten Melodies of Phleng Arak, Cambodia; The Kultrun of Cañon del Blanco, Chile; The Taskiwin of High Atlas, Morocco. Image: Sébastien Robert

How did the research you did for your thesis guide the way you approach and work with the musicians you encounter in various communities around the world now? How do you make sure you are not guilty yourself of exploiting, misrepresenting or appropriating the culture and world views of the communities you meet?

To the greatest extent possible – although in reality very difficult – I try to go there without any preconceived ideas on the outcome and let inspire myself by the people I meet. I believe that this absence of agenda, and to a certain extent, this lack of expectations, introduces a form of honest and humble dialogue, which is fundamental while working with indigenous communities. After all, it is all about people, and we should never forget that. Communication is the key to creating a climate of trust. By communication, I mean taking into account all the wishes, beliefs and worldviews from everyone involved and taking it from there.

Inevitably, such an approach raises new questions: How can we get to know the perspective of the indigenous community we are working with? How can we understand their rules, wishes and beliefs? I’m not only talking about language barriers here but different worldviews. And as my friend and environmental sociologist Darko Lagunas León questions: “Is this even possible to achieve from our Western reality?” I’m not claiming that I have the answers to this question, but I believe there are two ways – that go hand in hand – that can help us to get in the right direction.

One way of thinking about this is to try to deconstruct our cultural background: set aside our beliefs and thoughts, detach ourselves from our dialectical thinking, and decolonise our mind. Easier said than done, as language imposes a structure of possible ways of thinking, and this can easily lead to a sense of being out of control and out of place. This is not an easy process, but I believe that by merely being open and responsive, we may accept new concepts and understand new ideas. Another way is to work in a team. You need some translators to facilitate the conversation, but it is also interesting to work together with other artists, theorists and scientists, in the broad sense, coming from different backgrounds. A transdisciplinary collaboration can provide unique perspectives that, in return, offers reading keys to unlock the complexity of these Non-Western worldviews.

Ly Muts Pleng Arak Ensemble 2018. © Sébastien Robert

Ak, 2019. © Sébastien Robert. From The Forgotten Melodies of Pleng Arak

Your projects have brought you (or will bring you) to La Araucanía region of Chile, the High Atlas region in Morocco, Cambodia, etc. How do you choose the regions where you will travel? Are there specific criteria and levels of urgency of music and rituals that drive you to one community rather than another?

Up to now, I didn’t specifically choose the destinations of my projects but instead grab opportunities that have arisen through multiple ways in my network. Some might think that this is a very opportunistic approach, but in reality, it is a deliberate choice. In line with what I was explaining earlier, this strategy helps to go in the field with as few as possible expectations on the outcomes. Generally speaking, what interests me the most in the first place is the local context. That comes from my passion for geopolitics from a young age, which I owe to my father who taught me to ‘look under and beyond the maps’ to decipher the complexity of a territory. Besides an often denigration of traditional heritage practices and a lack of belief from the younger generation, these music and rituals are under threat due to intertwined technological, societal and ecological issues. They are symbols of the complexity of the world we inhabit.

In Cambodia, the Peng Arak almost vanished during the Khmer Rouge period (1975-1979) when music from past eras was forbidden and most of the musicians killed. Today, it’s the rise of modern medicine combined with the influence of Chinese medicine that threatens the future of this healing ceremonial music. In Chile, ancestral Mapuche rituals are under threat due to drastic changes caused by climate change, land expropriation and logging on the ecosystem in which they live harmoniously for thousands of years. In Morocco, the decline of the Taskiwin has its roots in the forced migration in the 1960s of thousands of young Amazigh (Berber) people to the mines of northern France which depopulated the region of its musicians.

That being said, my methodology is currently shifting as I am now researching the hidden threats posed by the ecological transition on indigenous communities around the world to see if my upcoming projects could follow a common thread. The building of electric vehicles, wind turbines and solar panels requires the extractions of rare earth metals and specific materials, which have disastrous consequences in remote locations. Whether in Papua New Guinea, where deep-sea mining is threatening indigenous culture, in Ecuador, where the exploitation of balsa wood devastated Waorani communities or in Finland, where miners hunting for metals threaten Sámi reindeer herders‘ homeland, the examples are numerous. If you dig deeper you realise that each of these communities has a specific and spiritual link with these materials, and some rituals are always associated with them.

Rite of Passage, 2020. © Charlotte Brand

The Kultrun of Cañon del Blanco, Chilean Andes 38°32’44.5”S | 71°40’44.2”W, May 2019

Your work The Kultrun of Cañon del Blanco studied the influence of the Kultrun – a Mapuche drum – on the crystallisation of the resin of a Mapuche sacred tree, the Araucaria Araucana. You carried the rhythms of the drum in the resin using a technique called sensitive crystallisation and documented their influence on the formation of the crystals. What have you learnt during that process?

I am still learning as this is an on-going project. All the theoretical frameworks of this project and the initial research have been developed during the Valley of the Possible residency in May 2019 in Chile. However, it took me more than a year to develop my installation Rite of Passage, which allows the drum’ vibrations to get into the crystals. The first things I learned from this process is patience and perseverance. The sensitive crystallisation is a complex and, as its name suggests, subtle technique. Any slight change in temperature, humidity and vibration during the process can influence the structure and the texture of the crystals. It took me a lot of time to understand it, but it is also a slow process in itself as it takes between 17 to 24 hours to grow one crystal. At some point, this project became too science-driven: trying to reach lab conditions of experiments with DIY equipment, spending days testing different types of crystallisations, and indirectly transforming my working studio into a 28,5°C sauna, the ideal temperature for crystal growth.

To counterbalance this, I also learned to follow my intuition instead of strictly academic papers on scientific methods. The challenge generally lies in the timing of such disruptive decisions as they will influence the rest of your project. In my case, it was the moment I decided to switch from the analysis of grown crystals to crystal growth. In other words, not to focus on the final crystals but on how the crystal goes from its fluid to solid state: its liminal phase. That is made possible thanks to the installation I built, which documents every minute, via a camera on top of the crystallisation chamber, the state of the crystal listening to the sound of the drum. The images captured are then gathered and speed up to create time-lapses where it is possible to see the crystal growing over time.

So far, the results of this time and scale shift in perception have been fascinating. Although too early to draw any conclusion, it seems that the different rhythms influence not only the structure and the texture of the crystals but also the speed of their growth. If this is true, it would mean that the resin of the Araucaria araucana tree can record the rhythms of the kultrun. I still need some time and space to experiment with this installation, which hasn’t been set up since my last exhibition at FIBER Festival in Amsterdam last September. In the ideal case, I would like to take it back to Chile, where this project was initiated, to finalise it and present its results back to the Mapuche community it is about. Therefore I need to be even more patient.

The Kultrun of Cañon del Blanco (Study of crystal growth), 2020

Your bio states that your work has been exhibited in the famous Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway. Can you tell us about that?

This exhibition was the outcome of my first project The Forgotten Melodies of Pleng Arak, where I translated the recording’s sonograms of Pleng Arak, a healing Khmer music in a coding system that I later engraved into a tablet. Each year, a selection of artworks that specifically spoke to the bio-cultural connections in agriculture and the links seeds have to society, ecology and culture, are deposited/buried/planted for eternity in the mountain alongside the Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Norway.

The music of Pleng Arak is performed in shamanic agricultural contexts to call spirits when there is no rain or crops are struck by a disease. I, therefore, thought sending the tablet there would be the most poetic way to preserve a trace of this disappearing music for eternity. However, I cannot tell much about the experience itself as I wasn’t physically there: the exhibition was too close to the birthdate of my daughter.

I finalised the tablet three days before being sent to Norway, which was a strange feeling to me, given this was the first artwork I ever made. Yet, a great reminder that I do not own anything I am working on, solely passing on a message.

What drives your practice? An urgency to celebrate music and rituals that might disappear soon? A curiosity about other cultures? A desire to translate the intangible into tangible artifacts?

My first motivation is to raise awareness on the uniqueness of these century-old indigenous rituals but also their fragility. Their loss is a profound and urgent topic, which I think we should all be concerned about as it brings to light the complexity and interconnectedness of the world we inhabit. Through my work, I am interested in finding ways to pay tribute to these rituals and preserve some of their characteristics without the pretentious idea that I will ‘save’ them or solve the local issues that are at hand. It is more about creating a dialogue between different standpoints and searching for possibilities to create an understanding of the connection between indigenous knowledge and the landscape.

That leads to my second motivation: to highlight the epistemological diversity of our world. This point particularly interests me as it constantly evolves through my field experience. Take, for example, my last project in Chile. It is deeply grounded in the Mapuche worldview that doesn’t separate nature and culture as we do in the West. This absence of dialectic thinking is rather hard to understand from our western reality as most of these connections are often imperceivable, invisible or inaudible. Besides a paradigm shift, technology is necessary to expose the unknown and bring different scales to our perception.

And that brings me to my last motivation: to explore alternative ‘recording’ mediums. To a certain extent, the simple answer to the loss of indigenous rituals would be to ‘capture’ them in audio or video format for conservation purposes. Yet, this has already been done in the past, and the current storage mediums are too fragile: vinyl, tapes and digital files have a limited lifespan. On top of that, they are standardised mediums, created from our Western perspective. In experimenting with long-lasting materials that hold a symbolic place in the traditions of the communities I meet (sandstone in Cambodia, Araucaria araucana resin in Chile), I aim to find ways to translate the sonic characteristic into visual forms that take into consideration their wishes, beliefs and worldviews.

Your work is grounded in field works and personal encounters so how has your practice adapted to the pandemic?

Besides the residency in Morocco planned in April 2020 postponed to 2021, my practice didn’t change much during the first six months of the pandemic, as I was working on my graduation piece, Rite of Passage. Because all my side projects got cancelled, I suddenly had the time and space to focus on this installation. To a certain extent, I think the pandemic worked in my favour. After my graduation in September, and perhaps a little naively, I thought the situation would quickly ease off and that I would soon be able to go back into the field. But I was quickly disillusioned. The recent postponement of the residency in Morocco to 2022 made me realise that the situation was still far from being solved. So, like many artists around me, I started to think about my artistic practice more locally. By researching music and rituals from where I originally come from (France) in my immediate surroundings (The Netherlands).

I first became interested in the bagpipes, a typical instrument from Brittany that I regularly listened to while growing up in Nantes. I have always felt a strong emotion when listening to this transcendental instrument. Perhaps listening to the work of Yoshi Wada would help to understand what I mean. I was surprised to learn that this instrument has been played for centuries in Northern Africa, Anatolia and the Caucasus before finding its way to Europe, which highlighted again how our view is deeply influenced by our cultural and historical background. Although that research did not lead directly to a new project yet, I do not exclude working with this beautiful instrument in the future.

In parallel, I have been invited by the festival Into The Great Wide Open to do some research on Vlieland, an island in the Wadden Sea in the north of The Netherlands. What started as an inquiry into the sonic landscape of the island, through underwater and surface recordings, transformed into experimentation with weatherfax, which are weather maps transmitted through radio waves. This disappearing and obsolete technique used since the 1940s to communicate with ships and isolated places takes inspiration from the work of Dutch cartographer and weatherman Nicolas Kruik (1678-1754). Born in Vlieland, he was the first to present weather data graphically, so to a certain extent, this technique originated from that island. Although it’s too early to say which direction this project will take in the coming months, I am grateful for this opportunity to continue my research during the pandemic.

Thank you Sébastien!