If you want to see a penguin, you go to the zoo. If you’re curious about dinosaurs and dodos, any natural history museum will enlighten you. But where do you go if you want to learn about spider silk-producing goats, anti-malarial mosquitoes, fluorescent zebrafish or the terminator gene?

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

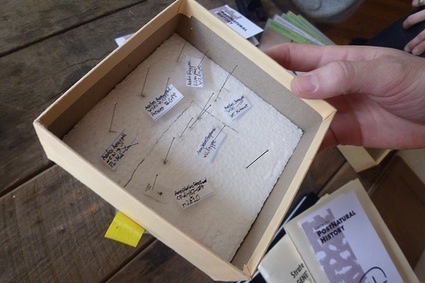

Model of a Biosteel™ Goat farm. Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Model of a Biosteel™ Goat farm. Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

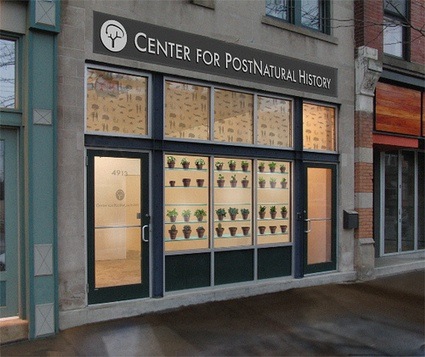

Right now, you can only rely on good old internet. But in June, the Center for PostNatural History will finally open its doors to anyone interested in genetically engineered life forms. This public outreach organization is dedicated to collecting, documenting and exhibiting life forms that have been intentionally altered by people through processes such as selective breeding and genetic engineering.

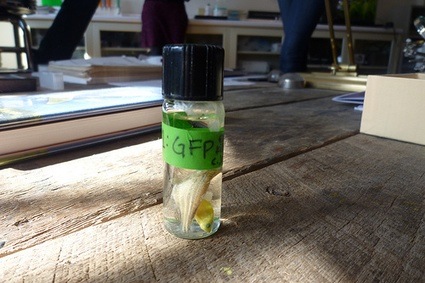

Transgenic chestnut tree leaf. Specimen collection, Center for Postnatural History. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

Transgenic chestnut tree leaf. Specimen collection, Center for Postnatural History. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

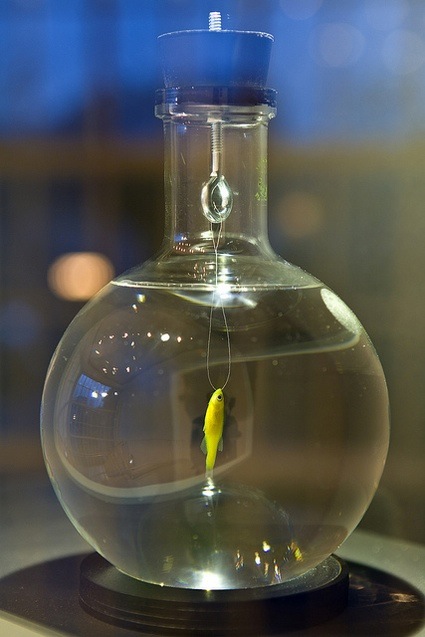

Transgenic zebra fish. Specimen collection, Center for Postnatural History. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

Transgenic zebra fish. Specimen collection, Center for Postnatural History. Photo: Kristof Vrancken / Z33

The center maintains a collection of living species when it’s possible. Otherwise they welcome the dead bodies of organisms of postnatural origin and in the absence of postnatural corpses, they present video and photography.

Along with its permanent exhibition and research facility for PostNatural studies, the center organizes traveling exhibitions that address the PostNatural through thematic and regional perspectives.

While we were in Pittsburgh, my book sprint* palls and i paid a visit to Rich Pell, the director of the The Center for PostNatural History.

The center wasn’t open yet when we visited Pell. All the images below were taken in the temporary studio where the collection is stored until the grand opening.

From left to right: Rich Pell, Andrea Grover, Luke Bulman and Jessica Young from Thumb, Claire L.Evans

From left to right: Rich Pell, Andrea Grover, Luke Bulman and Jessica Young from Thumb, Claire L.Evans

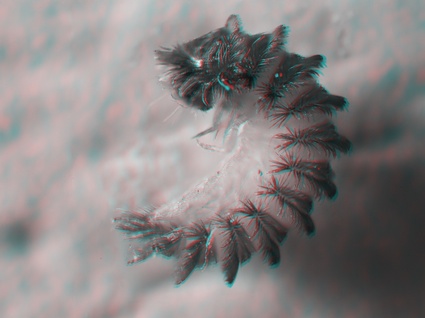

WT.Derm.ate1-10 “Ringo” Dermestid Beetle (stereoscopic) ate a whole collection of genetically modified mosquitoes (see image below)

WT.Derm.ate1-10 “Ringo” Dermestid Beetle (stereoscopic) ate a whole collection of genetically modified mosquitoes (see image below)

Hi, Rich! The Center for Postnatural History (CPNH) looks pretty unique to me but do you know if there are any center, organization or groups doing something similar anywhere else in the world?

Hi, Rich! The Center for Postnatural History (CPNH) looks pretty unique to me but do you know if there are any center, organization or groups doing something similar anywhere else in the world?

We wouldn’t want to stake our merit on claims of being first. There are in fact several natural history museums that have mounted exhibits that address issues of postnatural interest, such as the origins of domesticated Horses exhibit produced by the American Natural History Museum in NYC, or domesticated crops, such as the Seeds of Change exhibit at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC, or the transgenic bull Herman, who is on display at the Naturalis in the Netherlands. However, these are the exceptions to the rule. None of these museums are actively collecting, or interested in collecting, domesticated or otherwise genetically modified organisms. The evolutionary history that begins with the dawn of agriculture and the domestication of animals and continues on towards genetic engineering and synthetic biology is documented in bits and pieces, but not in any central location. To our knowledge there are no other museums that take as their mission to collect and exhibit the lifeforms that have been intentionally altered by humans.

It’s easy to understand why one can be fascinated by these modified organism but what made you decide to open a Center for Postnatural History? It’s a huge commitment.

It’s easy to understand why one can be fascinated by these modified organism but what made you decide to open a Center for Postnatural History? It’s a huge commitment.

Around seven years ago I was introduced to the emerging field of synthetic biology by Chris Voigt. At the same time, I was researching evolutionary biology and was struck by the fact that there is such resources devoted to documenting the natural world, but that the participation of humans in altering that living world is so rarely presented to the public. When I began looking at the collections of natural history museums I noticed that newly engineered organisms were not only absent from the collections, but that there was little interest in collecting them. The rare exceptions of Herman the Bull in the Netherlands, or Dolly the Sheep in Scotland, both point to the symbolic roll that these organisms can often play as icons, while the vast multitude of genetically engineered organisms remain undocumented. This seems like a significant blind spot in the public consciousness worth addressing.

When you start reading about the Roundup ready corn, the Triploidy Atlantic Salmon or other modified plants or insects, it is hard not to be judgmental. Some of the modifications are quite positive of course such as the mosquito that doesn’t transmit malaria. Still, i didn’t detect criticism in your discourse so far. So what is your position/strategy? Do you plan to be as neutral as possible in your presentation of the information and let the public join the dots?

We take it as our mission to allow for people to have the experience of arriving at an idea on their own. Personal discovery can be an incredibly transformative experience. Language that comes with a predefined worldview can get in the way of a person finding their own language and framework of understanding. As a strategy we make an attempt to describe the postnatural world without using the language of industry, academia or activism. In practice, this is not always possible, but it remains the ideal goal. Forming one’s own opinion can be a frustrating experience. We are sometimes contacted by people, months after coming across one of our exhibits, who are still wrestling with an issue. For us, this is encouraging. The issues are too important and too complicated not to be questioning our own assumptions and re-framing our own ideas in new ways.

Representation of Blood Wars by Kathy High

Representation of Blood Wars by Kathy High

When i visited what is going to be the Center in Pittsburgh, i noticed a short presentation of the CPNH hanging on the wall the text ended with the names of some of the people who helped you set up the exhibit at some point. I recognized a few names of artists. What is the role of artists in Postnatural History? Which place will you give to their work in the center?

Artists on the whole play a similar role in the creation of a postnatural history museum as they do in natural history. There are experiences to be created, things that must be documented, stories to be told. The difference is that some artists are also altering the living world as a part of the artwork that they make. In some of these cases, if the changes they are making are heritable and thus “in-play” evolutionarily speaking, then specimens of these lifeforms may be collected by the CPNH and cataloged alongside the organisms produced by universities, corporations and other individuals.

How would you define your own role at the CPNH? Is still the one of an artist? Or rather a curator?

The word “curator” is commonly used in natural history museums to refer to the people who manage the various collections of the museum, such as “Curator of Mammals”, “Curator of Mollusks” and so forth. Until such time as the collection becomes large enough to require more than one curator, I will hold the title of Curator of PostNatural Organisms.

Screenshot of the interactive visualization of Permitted Habitats– Genetically modified organisms released for field tests from 1987 to 2008

Screenshot of the interactive visualization of Permitted Habitats– Genetically modified organisms released for field tests from 1987 to 2008

I discovered your center at the Alter Nature exhibition at Z33 in Hasselt. I took with me some of the cards and they are colour-coded. ‘green’ is for ‘transgenic’, lila is for ‘mutant’, orange is for ‘hybrid’, etc. can you explain us the distinctions briefly? some are clear, others are more confusing to me…

These distinctions are significant, but not always separate or exclusive. Some may occupy more than one category. Some new categories may be added. Transgenic refers to a genetically engineered organism that has had DNA from one or more different species intentionally inserted into its genome. This kind of alteration is not possible with traditional breeding and was developed in the mid-1970’s. A mutant has had its DNA altered through the use of chemicals or radiation to induce largely random changes to its genome. Mutations occur all the time in nature, but are sometimes artificially selected for or induced by people. Most of the traditional vegetables we eat are very different in appearance and taste from anything we find in nature. These are the result of spontaneous mutations that were selected for by people over many generations, in the case of corn, thousands of years.

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Did you talk about the Center for Postnatural History to more ‘traditional’ natural history museums? How is the reaction of the curators and conservators over there about your own center? Would they invite you to set up a temporary exhibition in their space for example?

The response from natural history museums has been quite welcoming. We have been invited to meet with several of the largest natural history museums in the world. A common response from them is, “Why isn’t anyone else doing this?” However, none are willing to devote their own limited resources towards this area. Generally speaking, the biologists who curate natural history museums have a strong interest in natural ecology and the environment. The idea of studying the human-created habitat of an organism that has been raised in captivity is generally seen as profoundly boring by them. However, we have received invitations to exhibit specimens from our collection within their museum and are currently in negotiations regarding this.

The Centre will have a permanent exhibition as well as temporary shows. What will the opening temporary show be about?

Our first temporary exhibit will be a regional survey entitled, “Cultivated, Invasive and Engineered: PostNatural Plants of the Appalachian Region”. This will feature three themes. Indigenous medicinal and food plants that were cultivated by Native Americans and European settlers which have been collectively shared over time, such as Ginseng, Black Cohosh and Wild Yam, the direct ancestor of modern hormonal birth control. Secondly, invasive or “opportunistic” plants such as Kudzu, which was brought to North America as an ornamental plant from Japan at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and is now, lacking necessary predators, spreading rapidly across the continent. And lastly, newly engineered crops that are nearly ubiquitous in the US, but are highly controlled by the private corporations that own their intellectual property rights.

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Image courtesy of Richard Pell, Center for PostNatural History

Are there specific safety regulations you need to comply with to open the center?

We follow the law. There is nothing within our collection that requires any kind of special permit. We have no special access as compared to anyone else. There are many things we might like to exhibit in their living form but are unable to do so. We see this however as an opportunity, and find ways of exhibiting the absence of the subject as a way of building a discourse around the issues of regulation, containment, secrecy and intellectual property.

Are you free to show any kind of modified species?

Are you free to show any kind of modified species?

Newly engineered transgenic organisms must pass a regulatory process maintained by the USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service before they can leave the lab. As a result we are limited in what living organisms we are able to exhibit. For instance, the only transgenic vertebrate which we are able to exhibit are the commercially produced GloFish™ that expressed green, red and yellow fluorescent protein and thus glow under black light. These however can be purchased in many pet stores. We are however able to exhibit genetically engineered organisms that are dead. These were killed while at the lab with the support of the researcher in charge. Preserved specimens are not considered a contamination risk and are therefore not regulated by the US Department of Agriculture.

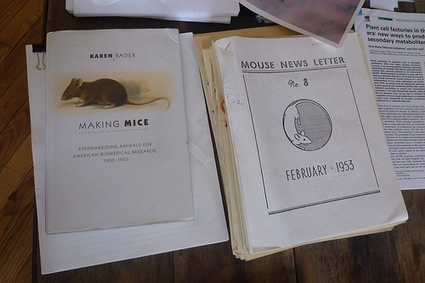

Lab Mice in the Natural History Museum (photo)

Lab Mice in the Natural History Museum (photo)

I was reading through the blog that documents your Smithsonian Research Fellowship and read this: ‘There appears to be an interesting relationship between military incursion and specimen acquisition. Particularly amongst the rodent collection, one can see the location and approximate start and end dates of most of the major American military projects of the 20th and 21st centuries. Reasons for this appear to be numerous and will be explored further during our stay here at the Smithsonian.’ Can you give us more details about this?

What makes the Smithsonian unique among museums, is that it is The National Museum of the United States of America. In some respects, the National Museum of Natural History is the biological memory of the State itself. One of the first things I noticed while there, was that there was a strong bias within the rodent collection towards places that our military has had a presence. The sites of wars, occupations and military exercises are all thoroughly represented. The reasons for this are many. In some cases they are collected by the military when they enter a new environment and are concerned about potential disease vectors, and the specimens eventually find their way into the National collection. But in other cases they are collected by Smithsonian researchers who are working in coordination with the military. Some of the larger collections of animals are from these situations and include: Fish and small mammals collected during the Operation Crossroads atomic tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946; A large assessment of biological diversity at the Nevada Nuclear Test Site following the suspension of atmospheric bombing in 1964; And a large collection of birds and mice collected during the Project SHAD germ warfare tests at Johnston Atoll in the mid-60’s. There are also a number of white lab mice and rats that were donated to the Smithsonian by the Walter Reed Medical Center and the National Cancer Institute who were developing them as model organisms to study the effects of radiation in the 1940’s. These specimens all quietly tell stories of the movements, fears and aspirations of the United States. They serve as examples of how deeply intertwined our cultural history is with our natural history and are reminders of how the project of science is never divorced from the cultural context in which it is conducted.

Thanks Rich!

The Center for PostNatural History will open its permanent space in June 2011 at 4913 Penn Ave. in Pittsburgh, PA.

The Center for PostNatural History will open its permanent space in June 2011 at 4913 Penn Ave. in Pittsburgh, PA.

The Center for PostNatural History is part of the exhibition HUMAN+: The Future of our Species, on view at the Science Gallery in Dublin until June 24, 2011.

* In case anyone was wondering, the book’s not ready yet, apparently it takes more time to proof read it than to write it.