Richard Mosse‘s practice has been described as a prime example of “sensor realism.” He appropriates and subverts equipment designed for surveillance in order to challenge documentary tropes and force us to look anew at images we’ve seen again and again. His images do not strive for photorealism but they still manage to challenge our perspective on the erosion of human rights and environmental crimes as well as our own attention fatigue.

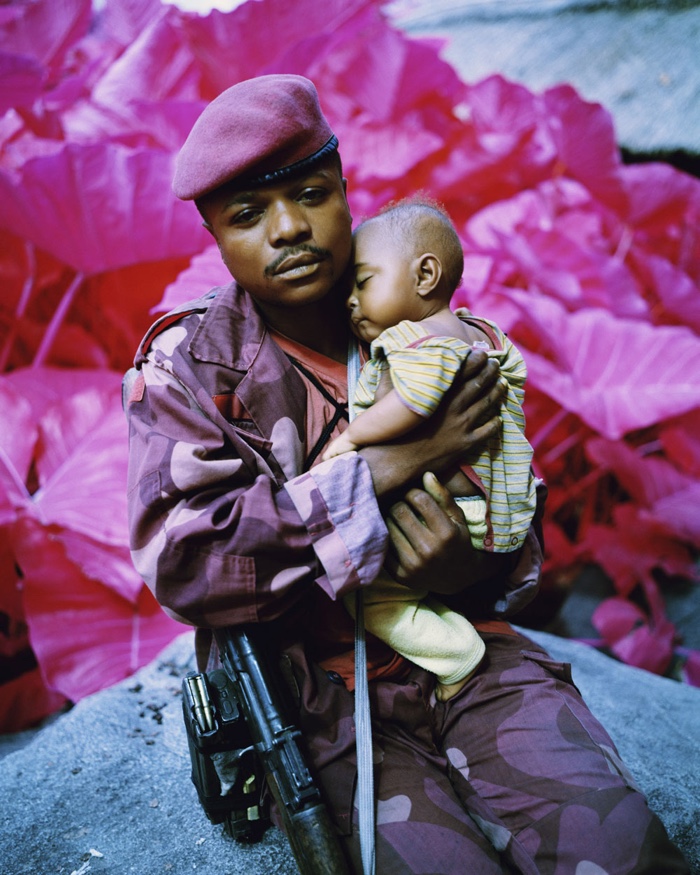

Richard Mosse, Suspicious Minds, DRC, 2012

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #88 (Lesbos, Greece), 2016

Richard Mosse: Displaced. Migration, Conflict and Climate Change, exhibition view at MAST in Bologna

Displaced. Migration, Conflict and Climate Change, the photographer’s retrospective opened a few weeks ago at MAST in Bologna.

The rooms that fascinated me the most are dedicated to the famous series Mosse shot on the battlefields of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a nation in a seemingly perpetual state of humanitarian disaster that the international political community seems to have consigned to oblivion.

Mosse shot the images using Kodak Aerochrome, an infrared military film technology that the company developed in collaboration with the US military in the early 1940s for aerial surveillance and camouflage detection. The now discontinued film is known for its ability to reveal a part of the light spectrum that is invisible to the human eye. Plants are green to our eyes because they reflect green light away from their leaves. But they also reflect infrared light that is invisible to our naked eyes. Using Kodak Aerochrome, vegetation shows up as pink and non-plant material (such as a camouflaged vehicles and fighters) that do not reflect infrared light appears darker.

Drenched in pinks, purples and reds, the lush Congolese landscape is so beautiful that it reminds you that this country could be one of the richest in the world. It has a dense tropical rainforest, a young population, many of the minerals essential to our digital and/or green future, it is home to fascinating cultures, etc. Yet, the DRC is the poster boy for resource curse and its name evokes violence and chronic instability.

While looking at the portraits of young members of rebel groups, I tried to remember the words the photographer pronounced during the press conference at MAST: “These are men who have blood on their hands.”

Richard Mosse, Vintage Violence, DRC, 2011

Richard Mosse, Madonna and Child, North Kivu, Eastern Congo, 2012

Richard Mosse, Thousands Are Sailing I & II, North Kivu, DRC, 2012

Richard Mosse, Of Lilies and Remains, North Kiva, DRC, 2012

Richard Mosse, Lost Fun Zone, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012

Richard Mosse, Platon, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012

Richard Mosse, Hombo, Walikale, eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012. The town of Hombo in southern Walikale Territory, on the border between North and South Kivu

Richard Mosse, Come Out (1966), Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, 2012

Richard Mosse, The Enclave, 2012–2013, 16 mm infrared film transferred to HD video. Installation view, produced in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo

It wasn’t until i saw The Enclave that I reconciled myself with the idea that these young men were indeed war criminals. Mosse’s six double-sided screens installation immerses you in a disorienting journey in the company of rebel groups who roam eastern Congo, spreading what looks like senseless devastation and unfathomable horror.

Mosse, cinematographer Trevor Tweeten and composer Ben Frost embedded themselves into armed groups and captured footage of daily life in the region. The images they brought back are brutal, haunting, they accompanied me for days after my visit to MAST.

Richard Mosse, Souda Camp, Chios Island, Greece, 2017

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #27 (Mediterranean Sea), 2016

Richard Mosse, Still from Incoming #96 (Lesbos, Greece), 2016

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming #293 (Sahara Desert, Niger), 2016

Designed for long-range border enforcement, battlefield awareness as well as search and rescue, the thermal camera Mosse customised for his Heat Maps series has been used by the military since the Korean war. The technology is now part of the EU arsenal to respond to mass migration, yet another a “problem” we would rather not to see. The instruments can detect thermal radiation, including body heat, from a distance of over 30km. Both day and night.

Working with the thermal camera was tricky. First, because it is registered as a weapon under international law and the artist needed special permits and the help of lawyers in order to be allowed to travel with it. It is also cumbersome and difficult to position. The shots are then taken automatically, following settings set up by Mosse. To make one large-scale panorama of the refugee camps, the photographer had to meticulously piece together hundreds of shots that were each focusing on just one detail in the refugee camps. Because the original photos were taken at different moments, some people may appear more than once on a single image, adding to the general feeling of eeriness.

The photographer also used the thermal military camera to film refugees and migrants as they were fleeing Syria, Iraq and elsewhere, turning them into hot-bodied ghosts.

The same scenes that we’ve seen countless of times in the media -overcrowded boats, rescue teams, people wrapped up in thermal fleece blankets, discarded life jackets – are made spectral but also more visceral.

The images concern every single one of us. Not just because global warming could turn us into climate refugees tomorrow but also because, as Mosse said during the press conference, “When we erode the human rights of refugees, we erode our own rights.”

Richard Mosse, Mineral Ship, Crepori River, State of Para, Brazil, 2020

Richard Mosse, Sawmill, Jaci Paraná, Rondônia, 2020

When the exhibition in Bologna opened, Mosse had just returned from the Brazilian rainforest where, he explained, environmental crimes are normalised.

Just like the project in the DRC was inspired by Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, set in an 1890s Congo wracked by violence and imperialism, the Tristes Tropiques series is influenced by the memoir that Claude Lévi-Strauss wrote to document his travels and anthropological work, mostly in Brazil. The book was published in 1955 but its assessments of the impact of globalisation and technological development on the environment and on cultures was premonitory.

This time, the artist turned to a camera used by both by scientists who investigate the effects of climate change on the rainforest and by agribusiness corporations eager to profit from the land. Mosse fitted the camera to a drone and flew it over sites of environmental crimes where it captured bandwidths of reflected light, many of which are invisible to the human eye. Experimenting with different colour combinations, the artist then created dramatic topographies that are disorienting for anyone who doesn’t know how to read them but that reveal the scale of the brutal degradation of the Amazonian rainforest. And the many ways through which such catastrophe can be achieved: plantations of palm trees, intensive soy bean farming, cattle farms, illegal mining and other forms of environmental criminality.

The series is impressive but they didn’t move me the way Mosse’s previous series did. I got lost in the composition, the vivid colours, the abstraction and found the images barely readable.

More images from the show:

Richard Mosse, Pool at Uday’s Palace, Salah-a-Din Province, Iraq, 2009

Richard Mosse, Beaucoup of Blues, 2012

Richard Mosse, Stalemate, 2011

Richard Mosse: Displaced. Migration, Conflict and Climate Change, exhibition view at MAST in Bologna

Richard Mosse, She Brings the Rain, 2011

Richard Mosse, Dionaea muscipula with Mantodea (from the series Ultra), Ecuador cloud forest, 2019

Richard Mosse: Displaced. Migration, Conflict and Climate Change is at MAST in Bologna until 19 September 2021.