Aljaž Celarc is a geographer with a master in documentary photography. Eva Paulich Seifert is an art historian with an MA in Visual Culture. Together, they are PlateauResidue, an artistic duo whose work addresses the perception of landscape ecology and climate change. Their installations have explored themes such as the sensory experience of biodiversity loss, the importance and ethics of the human management of forests, the consequences of climate change on Slovenian territories, the rewilding of areas that technology had drastically compromised, etc.

PlateauResidue, Ex Topia, 2017

PlateauResidue, Ex Topia, 2017

Hiša Mandrova / House of Mandrova. Photo

As a practical, logical and daring illustration of what can be done when you care about nature, Eva and Aljaž decided to abandon their life of exhibitions and residencies in European capitals and moved to Novi Kot, a small village in the middle of the Slovenian forest. They renovated an abandoned farmhouse and turned it into Hiša Mandrova / House of Mandrova. The wooden house is now an open learning environment where the duo passes on their know-how and experiences of regenerative food production, traditional wood construction and building a more respectful relationship with the living.

I met Aljaž a couple of months ago in Maribor where we were both participating in a panel hosted by KIBLA. I was impressed by PlateauResidue‘s decision to combine an artistic career with an experiment in rural, almost self-sufficient life. One would expect artists, designers, activists and thinkers who engage with issues related to pollution, global heating and loss of biodiversity to live a life that reflects their fights and values. Some do. Unfortunately, I can’t claim to have that kind of coherence. Hence my desire to discuss further with the artist:

PlateauResidue, Terra Ignota (video still), 2021

PlateauResidue, Terra Ignota (video still), 2021

PlateauResidue, Terra Ignota (video still), 2021

PlateauResidue, Terra Ignota, 2021. Installation view at Kino Šiška. Photo: Aleš Rosa

PlateauResidue, Terra Ignota, 2021. Installation view at Kino Šiška. Photo: Aleš Rosa

Hi Aljaž! The video installation Terra Ignota addresses the sensory experience of biodiversity loss. Its form is inspired by the dioramas we can find in natural history museums. Except that instead of showing idealised ecosystems, yours depict the decay of species in the Sixth Holocene Extinction. Isn’t this a bit dark and risky to have visitors face such a sad reality? What kind of emotional reaction did you hope to generate with the dioramas?

I think that any reaction is better than no reaction. We don’t try to direct people towards specific positive or negative experiences, that is why we use this pseudo-scientific aesthetic. We keep it as “neutral” as possible. What matters is to trigger conversations about extinction. It is indeed a dark topic. At the same time, it is also so removed from our everyday experience that we thought it was important to do this work, especially during the COVID pandemic when all the attention was focused on humanity and its problems. That was a moment when problems related to global ecosystems and caused by humanity became neglected.

How did visitors react to the installation?

A lot of people were conscious of the problem but many actually didn’t realise that humanity is also at risk of being extinct. The main argument of the work was about whether or not that is the case and why humanity has this self-destructive drive. That generated a lot of debate.

We also tried to make people aware that the sheer materiality of the world around us is so interconnected with life on Earth that even previous extinctions are embedded in this materiality. For example, limestone stone is a sedimentary rock made of debris from the skeletons of sea organisms. Mountains in Slovenia are made from limestone. It is something that is very hard to get your head around. Oil, gas and coal too are remains of creatures that used to roam our planet. 21% of the oxygen in the atmosphere is generated through the photosynthetic capacity of plants. It is happening on such a big scale that as a person we might find it hard to comprehend, we are so small in comparison. If humanity goes extinct, that really will not be a big deal for the Earth.

PlateauResidue, Sub Persona (teaser), 2019

PlateauResidue, Sub Persona, 2019. Installation view at Švicarija, MGLC Ljubljana

PlateauResidue, Sub Persona, 2019. Installation view at Švicarija, MGLC Ljubljana

One thing I discovered while reading about your video installation Sub Persona is what you call the “importance and ethics of human forest management”. One would think that you just have to leave forests in peace and perfect ecosystems would magically appear after a few years or decades. Can you explain to us why human forest management is so important?

Forest ecosystems have been so deeply disrupted by human interventions -such as selective logging or clear cuts- in the past that the relations between the trees and other plants in the forest are now completely off balance. That can lead to drought and other stresses related to climate change which in turn can cause further damage, even deforestation. In Slovenia, we now have to remove spruce trees which became an invasive species here. Before human settlements, there were no spruce trees in the region, just fir and birch trees. Today, spruce trees count for one-third of all the trees in the country. Spruces are more adapted to high elevations and to Scandinavian countries (where they come from.) This has been causing a lot of stress in forest growth recently. It is therefore crucial that we try and reduce this population, without causing more damage to the forest, and replace it with tree species that are better adapted.

Forests play a key role in carbon sequestration and storage. It’s the most efficient storage on land, after soil. Because we are the ones who (mis)managed forests in the past, we also have a moral obligation to help them gain back their optimal carbon storage capacity. At the same time, forests are also one of the few natural sources of sustainable materials, especially where forests are abundant.

How do you work on projects that touch upon science and the environment? Do you document yourself and develop the research on your own or do you get in touch with scientists and other experts to get help?

A bit of both. We like to have collaborations going on. We try to find experts and other knowledgeable people and then we gather information from various sources and try to come up with unique interpretations of the issues we engage with. That is what our workflow looks like. Over time, we have accumulated knowledge and then we connect dots and pieces that we articulate through art. Science tends to be very fragmented and work in silos but art has the ability to connect various areas of research to make emerge a bigger picture.

PlateauResidue, Apertures in the Landscape, 2022

PlateauResidue, Apertures in the Landscape, 2022

PlateauResidue, Apertures in the Landscape, 2022

One of your latest artworks, Apertures in the Landscape which was on view a couple of months ago at artKIT in Maribor, “explores the significance of the material remnants of past eras, the obscure technologies of the past and the process of returning nature to areas that have been altered by human technology in the past.” To investigate this question, the light and sound installation looks at two interconnected historical milestones. On the one hand, the Rapallo border that used to delimit the territories of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the Kingdom of Italy. On the other hand, the invention by A.G. Bell in 1880 of the photophone, the first wireless information technology. I missed the installation when I was in Maribor, it opened a few days after I had left the country. Can you tell us something about it?

That work is meant to be an atmospheric installation with light and sound that gives new insights into the recent history of the region while questioning how past events still affect landscapes today. Two years ago, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Rapallo border formation, a fortified border that was established between the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and Italy after WWI. To build the border, they clear-cut all the forest along the line that became the border and then they fortified it with quirky-looking bunkers and underground forts. They also used exciting technologies, some of them so futuristic that they seem to emerge from science-fiction movies. We used some of them in the work in order to try and visualise the landscape where they installed all these futuristic-looking stuff a hundred years ago and try to assess today’s view on the past and the future.

How is that area today? Did nature come back?

Yes. You wouldn’t believe that there used to be a border there if you haven’t seen the remains. Nature has taken over the area. This is inspiring for us. After a hundred years, all that innovation and fortification have become almost archaeology. This power of natural processes to take back control over an area that had been devastated is very promising. Chernobyl is another great example. If tourists were not allowed there, within 50 years, you wouldn’t even see human constructions, they would all be overgrown.

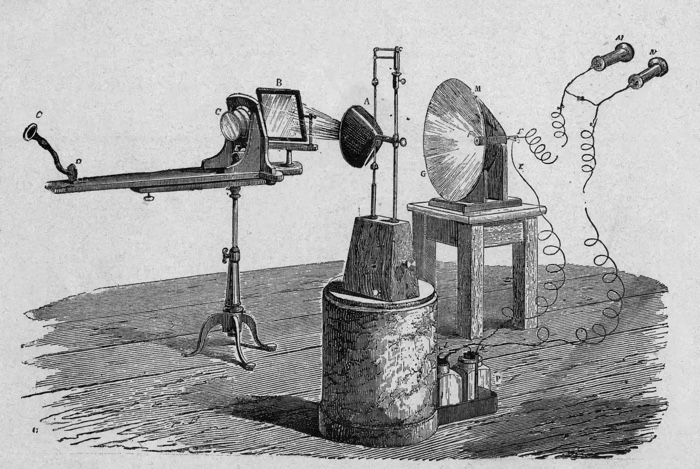

Alexander Graham Bell’s photophone, a device that allowed for the transmission of sound on a beam of light

The installation also made use of an invention that A.G. Bell created in 1880: the photophone, the first wireless information technology. How were you using the Photophone technology?

We used it in the installation. We made these lamps that you would hold in your hands. As you entered the dark space, the lamp would not only light an area but would also transmit sound. Wherever you would point the light, there were two big images, each 2m by 1,50 m, in the dark. They had photocells that would receive the light the beam and that triggered the sound. The whole experience consisted in getting to know the place using the light and getting the sound in return was interesting, both for the viewers and for us to work with.

So you were using a technology that was developed almost 150 years ago and that technology sounds quite sophisticated. Did you have to use expensive, edgy technology?

Not at all, it was all very DIY. The first photophonic technology didn’t even use electricity. It was actually just a very thin mirror that would resonate when a person spoke behind it. The photocells on the other side would pick the waves generated by the voice. We made it using regular electronics, hot-wiring things together.

Hiša Mandrova. Photo courtesy of the artists

Hiša Mandrova. Photo courtesy of the artists

You both left urban life and moved to an old wooden house in Novi Kot in 2019, in the hinterland of the forests of Gorski Kotar and Snežnik, where you created the Hiša Mandrova/Mandrova House project in 2020. The workshops and other activities you organise there are dedicated to creating, regenerative self-sufficiency, manual woodworking, and reviving the area’s building heritage in question. where you organise workshops about gardening, wood construction, soil regeneration, etc. How does Mandrova’s House project feed into your activities as artists? And vice versa?

For practical and marketing reasons, Hiša Mandrova and our artistic practice are presented separately. From the creative point of view, however, it is just one thing. What we do here at Hiša Mandrova is more practical. Whenever we feel the need to make something more sophisticated or research-orientated then we start developing art projects.

Our next art project is already in the pipeline and it emerges from what we do here. It is inspired by the separation between humans and animals. It is a topic that has become quite popular because of the scandals around industrial farming and industrial slaughterhouses. There are ways to co-exist with animals that are ecologically sound. As well as beneficial for animals, humans and the environment in general. We want to present that in an aesthetic way that would convey this idea of a more harmonious co-existence and condemn industrial slaughtering. Here at Hiša Mandrova, we keep animals and we can’t even imagine life without them any longer. Some activists would ban keeping animals at all. I personally find that strange.

Hiša Mandrova. Photo courtesy of the artists

Hiša Mandrova. Photo courtesy of the artists

Do Hiša Mandrova/Mandrova House and your artwork reach different types of audiences? Or do they reach the same public?

Whenever we do something at Hiša Mandrova, we systematically try and communicate them to our contacts via emails and social media campaigns. We also plan to eventually extend to foreign markets as well by making the workshops and activities in English so that people from abroad could join us and participate. The audiences do overlap through a certain interest in environmental issues. We try to educate our audience both through art projects and Hiša Mandrova projects.

We try to give the public the intellectual quality and values that they deserve. With our works, we could reach more people if we reduced the intellectual level and were more lowbrow but we don’t want to go down that road. A reason for that is that the way you communicate conditions what you get back from the audience. That is why we do not put focus on growing our audiences too much. Instead, we try to work on the engagement and the quality of the audience. Both in our artistic practice and in Hiša Mandrova activities. I think that it is something that people immediately perceive and appreciate. They crave good content, especially online. There is so much dumb content on the internet, we don’t need to add to that.

How many of you are working at Hiša Mandrova/Mandrova House?

We kickstarted the project with a team of five people. Now it is just us. Plus, one external mentor for the workshops whom we hire when we need some very specific expertise. In the beginning, we worked with someone who was working on the marketing strategy, then someone who was researching the market and then some general adviser. We got some EU funds to pay them and develop the business idea. After a year, we felt confident enough to do everything ourselves: from social media to raising pigs. That is a lot of work. We developed a certain level of professional efficiency and that made it hard to find a reliable person to delegate to. Eva and I always give 100% to everything we do and, as a result, we have very high standards.

Any upcoming project, field of research or event you could share with us?

Right now we are busy reflecting upon socio-economic systems that would be fair to both people and the environment. We exchange a lot of ideas on that topic with researchers at the moment.

Thanks Aljaž!