Paula Humberg is a photographer, bioartist and biology student whose works make visible a series of ecological realities we tend not to be aware of: the plight of endangered mammals in the Baltic sea, the drop in pollinator populations in the Arctic, the so-called pests that are deemed “scientifically meaningless”, etc.

Paula Humberg, Causes of Death, Untitled, 2016

Dispersal, Humberg’s latest photo series and field experiment, visualises the effects of pollinator decline in Greenland, an Arctic region where climate is warming faster and the ecological communities are simpler and, thus, more vulnerable to the effects of climate disruptions. Another of her photographic works -perhaps the most heartrending I’ve seen this year- documents necropsies that are conducted on two marine mammals facing a number of human-induced threats: harbour porpoises and the Saimaa ringed seals.

Moving, eye-catching and featuring humble creatures, her projects bring about the kind of conversations that we might not be ready for but urgently need to engage in.

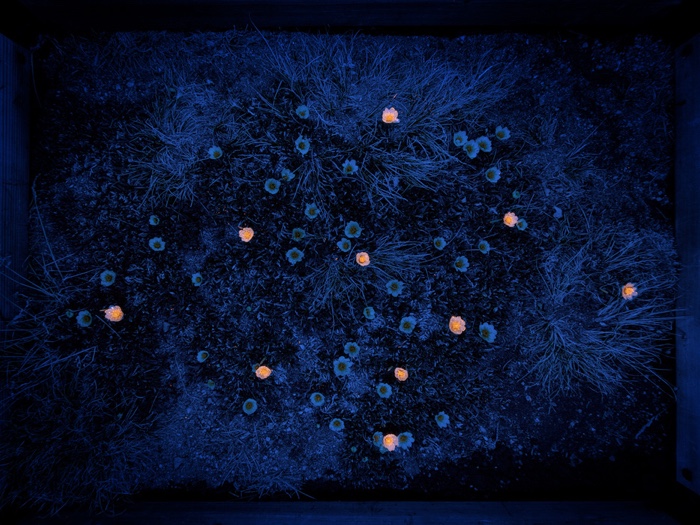

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Slot A2 at 0h, 2018

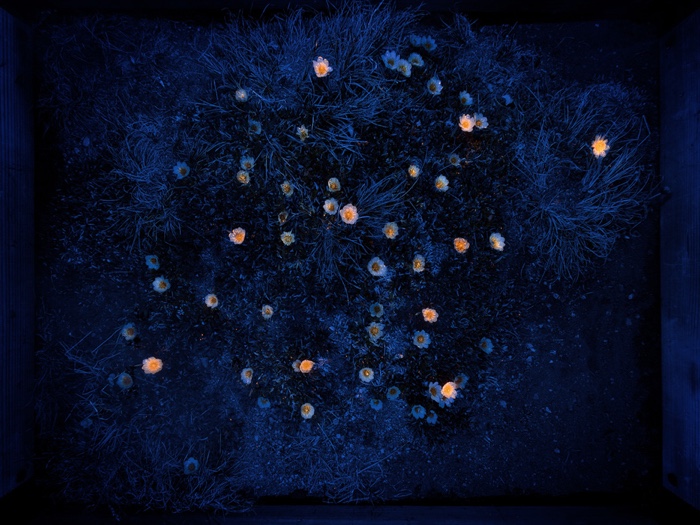

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Slot A2 at 72h, 2018

I contacted the artist as soon as I encountered her work in the excellent book Art As We Don’t Know It published a couple of weeks ago by the Bioart Society and Aalto University. Here’s our exchange:

Hi Paula! You are both a biology undergraduate student and a photographer. How did you go from photography to biology?

Actually it was the other way around, although I’ve always had trouble deciding whether to choose art or biology. I started studying biology over ten years ago but switched to art before completing my degree. While still studying arts, I begun having regrets and decided to finish the biology degree as well. My dream was to pursue a career in arts and combine my practice with methods and topics that are borrowed from biological research. At first it felt a little unrealistic, but in the past two years I’ve come to realise that it’s almost exactly what I am doing now.

Dispersal, a photo series and bioart project that visualises the effects of pollinator decline and climate change, was developed at Zackenberg research station in Greenland in collaboration with biologist Riikka Kaartinen. How did you get to create an artwork in a research station and work with a biologist? Was it the result of a call? Or were you the one who contacted them directly, asking if they’d help you with your project? How did it start?

Riikka and I met when we were both on a journalism course that was targeted to biologists and biology students. She had an ongoing research project at Zackenberg station and I found that really intriguing. The course was mainly about how to communicate scientific topics to a wider audience, and we had that in mind when we started talking about collaborating. In my experience biologists are often interested in sharing their findings to the public but it can be difficult for many reasons. We wanted to create an experiment that visualises the effects of climate change and also present the results in a format that’s more approachable than research papers tend to be.

I managed to get funding for the project only a few weeks before we were supposed to leave for Greenland, so I had almost lost hope I’d get to go. Travelling to the station is very costly because it’s so isolated. When I was there, spending my days netting flies for the project, I sometimes felt a little absurd. But I think that with all the environmental problems, it’s important people try to make new connections and look for alternative approaches. I was apparently the first artist to ever visit the station.

Biologists at Zackenberg estimate that the abundance of pollinating flies has decreased by up to 80% in the area over the past few decades. How about bee populations? Did they undergo similar drops in population too?

There are only two bumblebee species in Greenland and apart from honeybee colonies that were brought by humans, no other bee species live there. This is why muscid flies are such important pollinators in Greenland.

I realise my remark is going to sound very naive but i had assumed that with warming temperatures, populations of insects would have increased in Greenland. How do scientists explain the dramatic decrease in fly populations? Are other types of insects appearing and taking their place?

No, that is a good question! There is still a lot of research to be done on the topic (and I’m not an expert) but it seems some insect groups are indeed benefitting. Some research done at Zackenberg indicates the numbers of parasitic insects and insects that consume plants are increasing. On the other hand also detritus-eating insect populations appear to be declining. The distribution of species is changing as well. Some are moving northward along with the warming weather and therefore new species can appear.

Climate change isn’t causing just warmer but more extreme weather and, in some parts of the world, increased precipitation. I visited Zackenberg in 2018 after a winter that had seen a new snow record. The snow melted so late that animals and plants widely failed to reproduce. We had trouble finding enough flowers and pollinators for the experiment and there were hardly any birds around. Even with less extreme years, climate change can shift the beginning of flowering season. As pollinators aren’t adapted to this, a mismatch between plants and pollinators can appear.

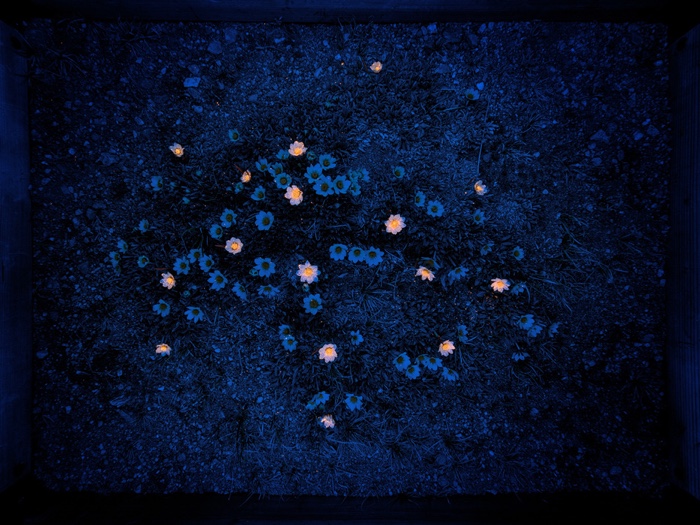

Why put fluorescent pigment on 20% of the flowers in each patch only?

The idea of the experiment was to see how pollination succeeds (that is, pollen is spread from one flower to another) with different pollinator compositions. To follow the spread of pollen, we dyed it with fluorescent pigment. The pigment was put on approximately 20 % of the flowers so that we could see how many new flowers would have the pigment after the experiment. In the tents that had less muscid flies the pigment spread very little.

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Slot A1 at 0h, 2018

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Isolation Tents, 2018

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Dryas octopelata, 2018

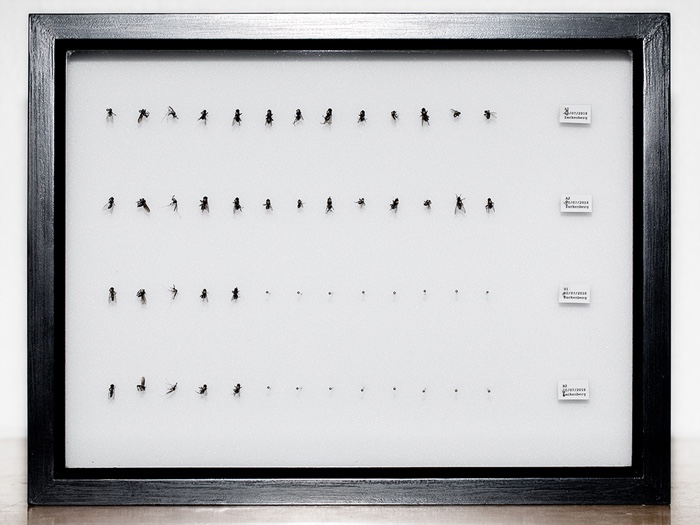

Paula Humberg, Dispersal, Test Assemblages, 2020

Why did you decide to include in the final artwork a collection of pollinators that were used for the test? What do their little bodies bring to the overall work?

As nature at Zackenberg is tightly protected, we were required to collect all traces of the fluorescent pigment. This meant also collecting and euthanising the pollinators. I definitely didn’t want to throw them away, but I also thought it might be a good idea to show what kind of pollinators were used. If you look closely, you can see some of the insect pins are empty; I wanted the collection to reflect what’s happening at Zackenberg.

Paula Humberg, Causes of Death, Untitled, 2016

Paula Humberg, Causes of Death, Untitled, 2016

Causes of Death deals with the human-induced threats to two endangered mammals, the Harbour porpoise (the Baltic Sea subpopulation) and the Saimaa ringed seal, through necropsy conducted on these animals. It’s not a series that is easy to look at. We know animals die, we’re just not used to seeing them dead. Unless it’s on our plates and then we can pretend they are just “meat”, not sentient creatures and that they have ended their life peacefully. Why did you choose to focus your project on Harbour porpoises and on Saimaa ringed seals?

I got interested in the harbour porpoise while I was writing my BSc thesis on the status of the species in the Baltic Sea. I realised not many people even knew what a porpoise is. It was quite surprising as they are the only whale species in the Baltic Sea. I was originally going to focus only on porpoises and the threats they face from fishing. However, I encountered some problems in Germany where, because of political reasons, I wasn’t allowed to photograph animals that had died from getting tangled into fishing nets.

I had to rethink the whole project. Since fishing is just one of the problems, I decided to emphasise more the complexity of the threats and the research work that follows. The Saimaa ringed seals also face human-induced threats but they are quite popular in Finland, and due to conservation efforts their population has been growing. So, in a way, their story is a more positive one, even though climate change continues to be a major threat.

Paula Humberg, Causes of Death, Untitled, 2016

Paula Humberg, Causes of Death, Untitled, 2016

What did you learn during these necropsies?

Every year just in the North Sea thousands of porpoises die because of fishing. However, because fishermen are worried for their livelihood, they can be reluctant about co-operating with researchers. Very many fishnet drownings never get reported. The researchers have to be quite discreet if they want to build better communication with the fishermen. I didn’t attend just the necropsies but also travelled with the research institute staff when they collected carcasses from local farmers. There are volunteers who collect and keep stranded corpses frozen until the institute staff picks them up. This system has helped with building trust between researchers and the public.

I also learned about the workflow – at the research institute in Germany the researchers go through a large number of carcasses and the work can be really hectic. The carcasses that are in best condition get examined more thoroughly. Porpoises are often loaded with parasites: they are in the lungs, stomach, ear canals, intestines and so forth. It’s suspected that pollution weakens their immune system, but unfortunately the institute’s budget doesn’t allow for regular analysing of environmental pollutants.

While reading the short text that accompanies your photos, i was particularly moved by the mention that one of the reasons why Harbour porpoises are endangered is disturbance from noise. Do you know anything about the sources of these noises? One would usually expect industrial pollution, overfishing, the presence of invasive species as reasons for the loss of a species. How bad are noise disturbances for the preservation of endangered (or non-endangered) species?

It’s still a topic that urgently needs further research. In the Baltic Sea the most common noise sources are traffic, construction and wind turbines. The Baltic Sea is very busy with cruise and cargo ships and other vessels which of course cause other problems beside noise too. Overall the cumulative effects of all threats are very worrying. For example, if the immune system is already compromised because of pollution, it can be more difficult for the animals to cope with any further stress.

And as far as you know, have measures been implemented to save those species since researchers have discovered the reasons for their slow disappearance?

The Saimaa ringed seal is doing a little better these days even though the population size is still small. Fishing is forbidden in the main breeding areas and some areas have been turned into conservation areas. When there’s not enough snow, volunteers help with plowing snow into piles in which the seals can nest. The harbour porpoise is in some ways a more difficult case. Things have been done but further action and collaboration from the Baltic nations are definitely needed.

Paula Humberg, Side Catch Collection I, 2015

Paula Humberg, Side Catch Collection II, 2015

Paula Humberg, Side Catch, Own Collection IV, 2015

I also found Side Catch strangely moving. The way you dispose of the insect bodies into the boxes gives them a life, even seems to reflect better their living conditions. Could you comment on some of them? Why is the earthworm in Own Collection IV all alone? Why are the harvestmen in Side Catch Collection II occupying the bottom of the box, for example?

The boxes look superficially similar to a scientific entomological collection but here and there the norms of traditional presentation are broken as I wanted the specimens to have a life (or death) of their own.

The series is in a way built around a comment from a beekeeper who gave me dead honeybees. She wanted to know how I would use the insects and was worried the queen would get separated from her workers. This made me decide the queen should be surrounded by her caring workers, but there is also another box with workers that appear “more dead”. Earthworm specimens are typically preserved in liquid. I pinned mine into its own box, as a kind of tribute to the ones that get constantly smashed under shoes or car tyres.

Any other upcoming events, fields of research or projects you could share with us?

I do have a very exciting field trip and project coming up! I’m travelling to a biological station in Peru and will work there for about one month. My current plan is to make video work that has to do with biodiversity decline and moths. I’ll try to use moth abundance as a proxy for biodiversity, and the final work will visualise how biodiversity is higher in primary than in intervened rainforest. This time I’m travelling alone but the final work will be done in collaboration with a researcher who studies machine learning.

Thanks Paula!