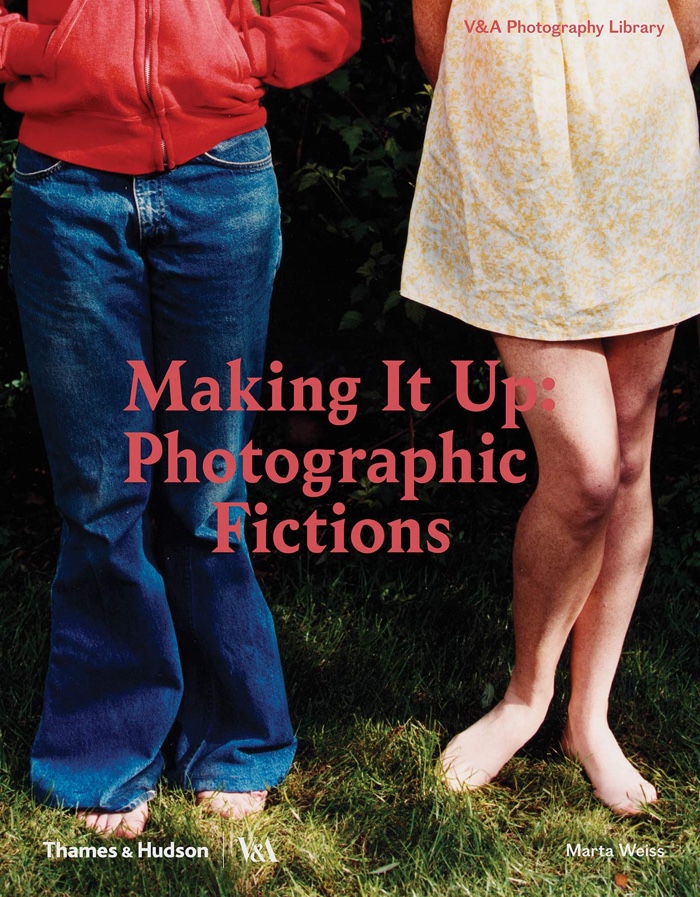

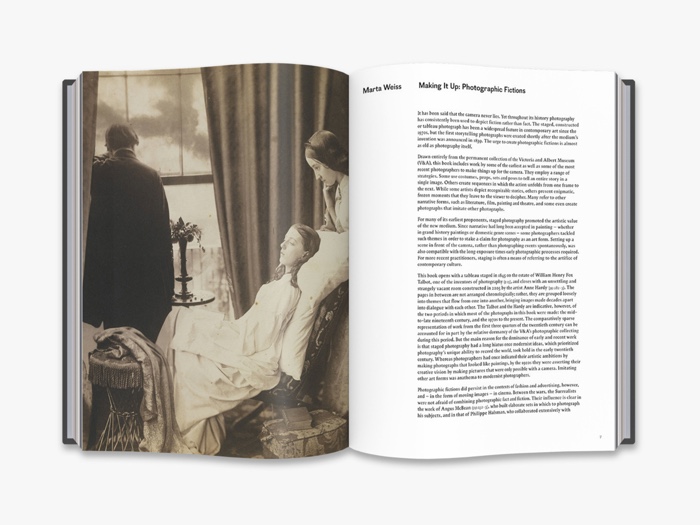

Making It Up: Photographic Fictions, edited by Marta Weiss, Curator of Photographs, Word & Image Department, Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

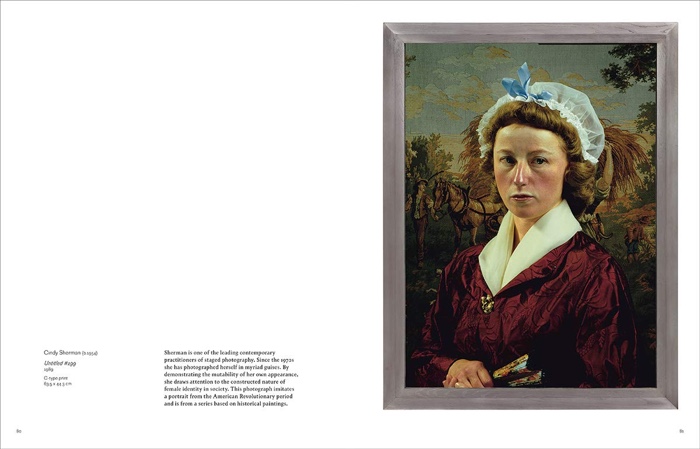

Publisher Thames & Hudson describes the book: Presenting work from the earliest through to the most contemporary of photographers, Making It Up: Photographic Fictions challenges the idea that ‘the camera never lies’. With over 130 photographs supported by extended commentaries and an introduction, the book illustrates that, though we often recognize the staged, constructed or the tableau as a feature of contemporary art photography, this way of working is almost as old as the practice itself. Remarkable in themselves, these photographic fictions, whether created by such early practitioners as Lewis Carroll or Roger Fenton, internationally renowned artists such as Cindy Sherman and Jeff Wall, or contemporary figures such as Hannah Starkey and Bridget Smith, find new and intriguing relevance in our so-called ‘post-truth’ age.

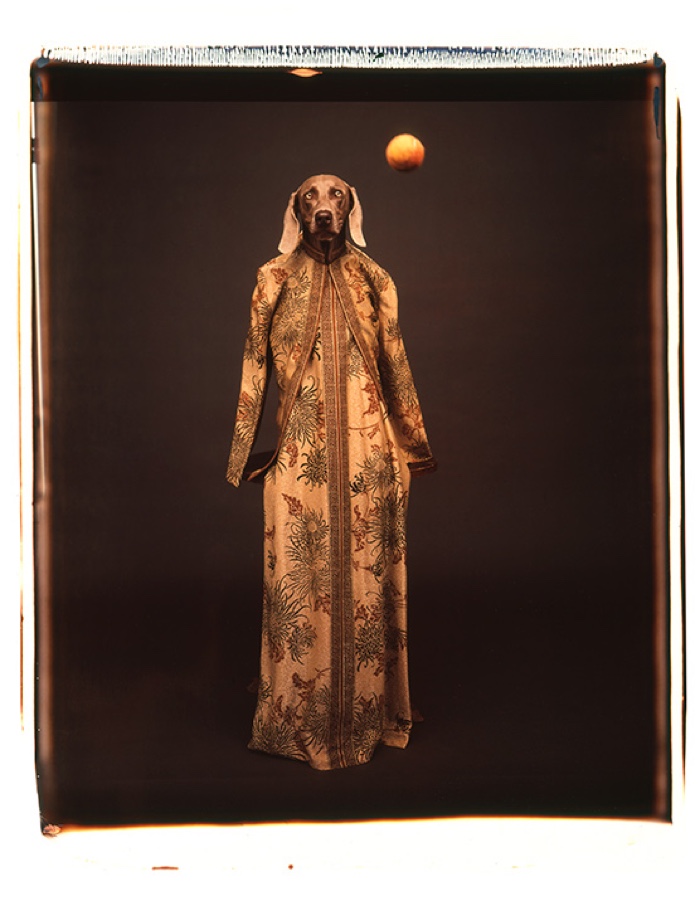

William Wegman, Dressed for Ball, 1988

The photographic medium has been used to fabricate fictions and fables almost ever since it was invented. Spontaneity, after all, wasn’t compatible with the long exposure times that early photography demanded. It was tempting to use the new medium not just to document reality but also to carefully orchestrate scenes and even narratives.

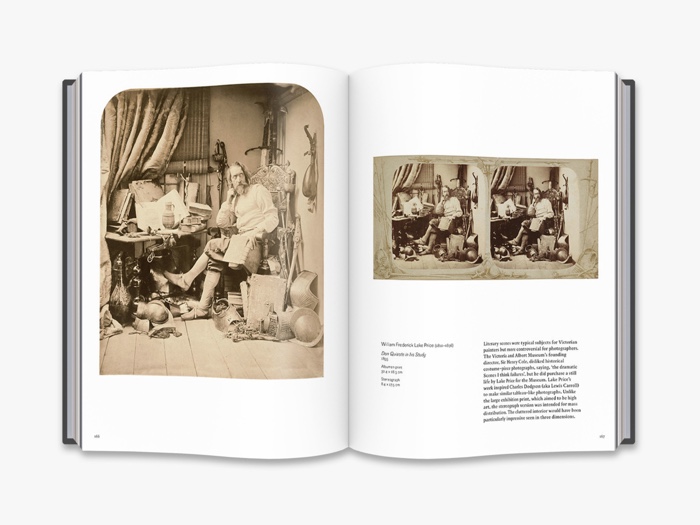

Some 19th Century photographers composed made-up tales as a social activity, little tableaux were then playfully staged to reproduce moments from history, to shape family stories or to fulfill the fantasies of an elite that dreamt of living a “simple”, working-class life for an afternoon. Other early photographers elaborated theatrical narratives in a bid to convince critics and other viewers that photography was an art form as respectable as painting.

Gohar Dashti, Iran, Untitled, 2014

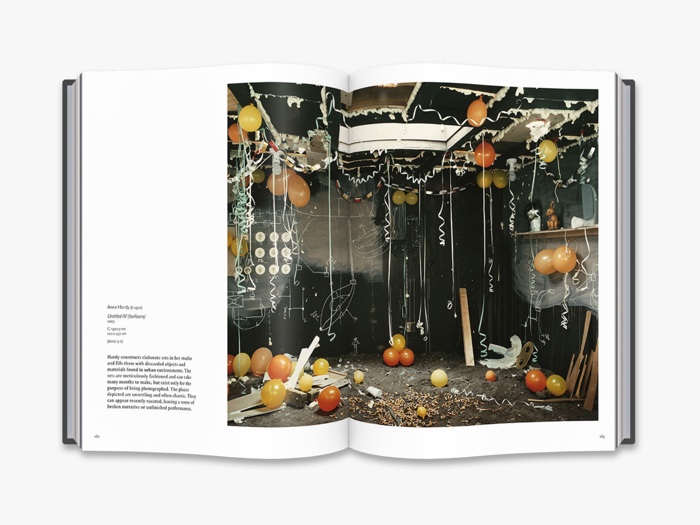

Today’s photographic tools allow for unplanned and instinctive snapshots. Yet, carefully choreographed tales haven’t lost any of their appeal. Story-telling nowadays comes with other aspirations though. Some artists use fiction to critically reflect on their medium of choice or to comment on current social and political conditions.

I grabbed Making It Up: Photographic Fictions because i had visited and enjoyed an exhibition of the same name a few years ago at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The book is not really a catalogue of the show but a publication that expands on it, with more details, more examples and more space to reflect on the use of photography to compose stories. All the photos in the book are drawn from the permanent collection at the V&A. Instead of presenting the images in chronological order, curator Marta Weiss plays with themes and aesthetics and makes early photography converse with works by contemporary artists.

I found the book as eye-opening, entertaining and fascinating as the exhibition. Here’s some of my favourite photos and stories from the publication:

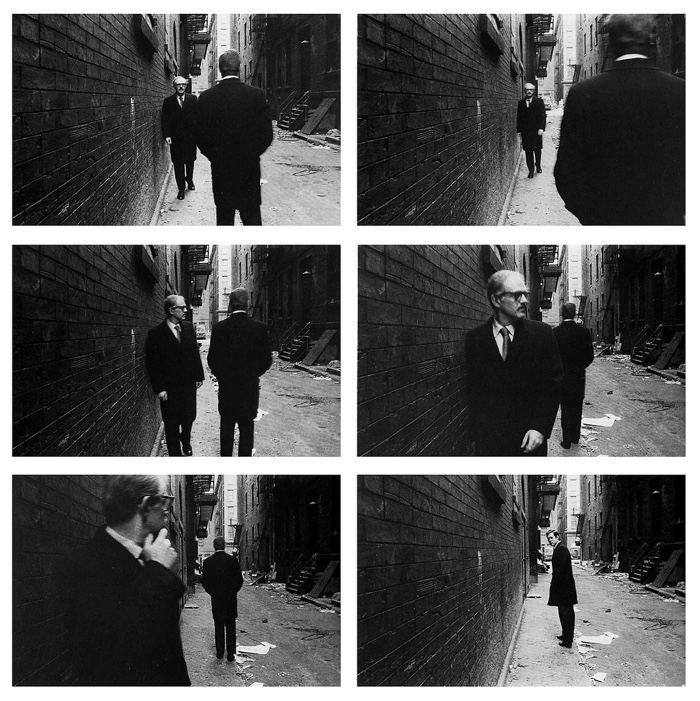

Duane Michals, Chance Meeting, 1972

Duane Michals’s sequences of photographs suggests a narrative. Two men in suits pass in an alleyway, exchange a glance and walk on. Nothing else happens but the encounter seems loaded with significance and perhaps danger. It’s one of the first works in which Michals addressed what it is to be gay in a homophobic world.

Henry Peach Robinson, The Story of Ridinghood, 1858. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

When Henry Peach Robinson exhibited his series that reconstructs key moments of the Little Red Riding Hood in 1858, some critics found it charming. Others, however, believed that fictitious photographs like these were an inappropriate use of a medium perceived as realistic and truthful.

Henry Peach Robinson, Fading Away, 1858

Robinson was also an early proponent of the photomontage. Fading Away combines five separate negatives to produce the intimate scene of a grieving family gathered around a young woman dying of tuberculosis.

Although the scene was imaginary, some viewers felt that it was too painful to be tastefully rendered by a medium as ‘literal’ as photography. The controversy, however, made Robinson famous in England where he was one of the leaders of pictorialism, a movement which promoted photography as an art form rather than a mere visual record of reality.

Tom Hunter, Woman Reading a Possession Order, 1997

Woman Reading Possession Order, is part of a series of work Tom Hunter made of a group of people experiencing housing problems in his neighbourhood of Hackney in London. The composition, light and colours echo Vermeer’s painting Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window, 1657, giving composure and dignity to the main protagonist.

Richard Polak, The Artist and His Model, 1914. © Victoria and Albert Museum

Dutch photographer Richard Polak built sets that reproduced the domestic interiors seen in the paintings of 17th century painters Johannes Vermeer and Jan Steen. He then photographed actors dressed in attires typical of that time.

Yinka Shonibare CBE, Diary of a Victorian Dandy: 11.00 hours, 1998

Yinka Shonibare’s Diary of a Victorian Dandy series depicts a day in the life of a fictional dandy, from his late morning rise, to his afternoon business and social activities, to an orgy at 3 a.m. The photographs resonate with William Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress (1735), which chronicled the squandering of the prodigal son of a rich merchant. Devoid of the moralizing message of Hogarth’s paintings, Shonibare’s work inverts the stereotypical roles of the time: the dandy is a black gentleman (a role played by Shonibare), his entourage is white.

The work seems to echo Shonibare’s own experience as an outsider who uses his flamboyance, wit and style to penetrate levels of society which would otherwise be closed to him.

The photographs required an elaborate production. Shonibare employed professional actors, a make-up artist, a stylist, a photographer and the director of BBC costume dramas for a shoot ‘on location’ at a stately home.

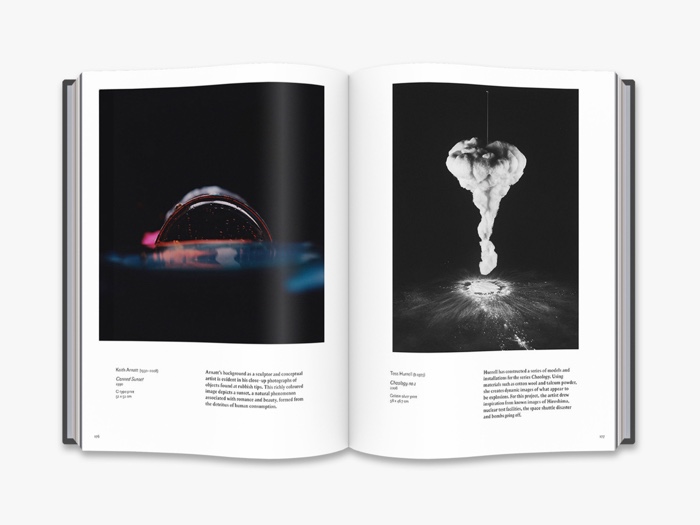

Tess Hurrell, Chaology no. 1, 2006

Tess Hurrell recreates in her studio atomic bomb blasts, space shuttle disasters and other explosions. She sculpts the scenes using cotton wool, talcum powder and string and then captures them on film.

Bridget Smith, Glamour Studio (Locker Room), 1999

Glamour Studio depicts an empty stage set used in the porn industry. The photo is part of a series that catalogues architectures of desire.

James Elliott, Mary, Queen of Scots. A Prisoner, c. 1860. © Victoria and Albert Museum

As in today’s period dramas, the sets, props and costumes used to imagine and stage this scene would have transported viewers to another time. The tableau was seen in three dimensions through a stereoscope (the Oculus Rift of Victorian times!), making the experience even more immersive.

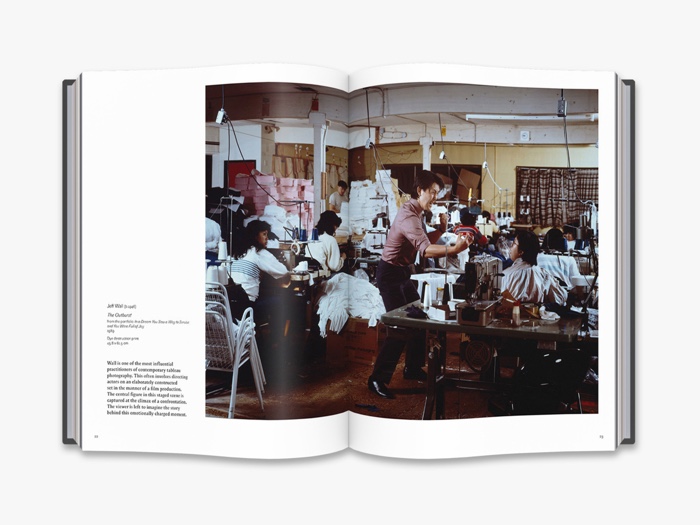

Inside the book:

Previously: Making It Up: Photographic Fictions.