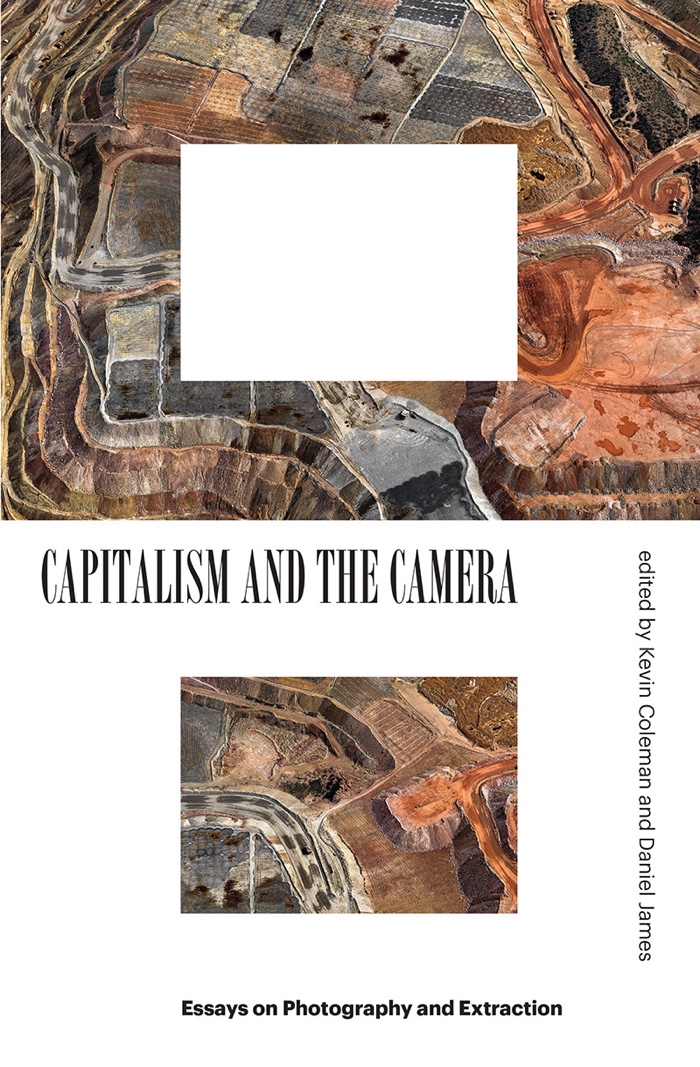

Capitalism and the Camera. Essays on Photography and Extraction, edited by Kevin Coleman and Daniel James. Published by VERSO.

On Verso’s page: Photography was invented between the publication of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels’s The Communist Manifesto. Taking the intertwined development of capitalism and the camera as their starting point, the essays collected here investigate the relationship between capitalist accumulation and the photographic image, and ask whether photography might allow us to refuse capitalism’s violence—and if so, how?

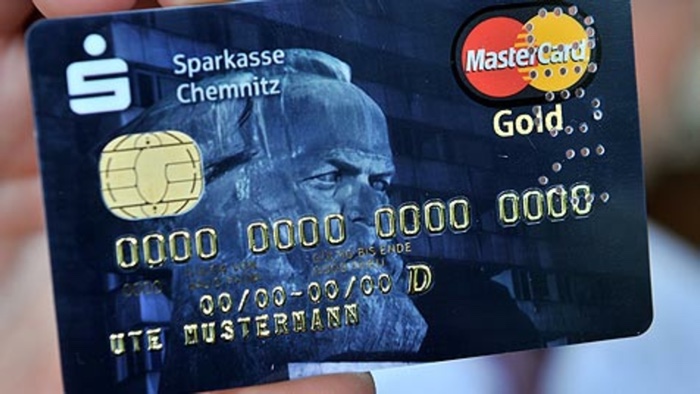

The 2012 card edition of the Sparkasse Chemnitz in Germany (photo)

A book that postulates and interrogates the connections between capitalism and photography, what’s not to like? Capitalism and the Camera is a collection of essays that challenge the idea that photography, and in particular documentary photography, is intrinsically good because it “raises awareness”. The exploitative nature of the camera manifests itself in different ways: it emerges with the physical origins of the medium, the polluting extraction processes and the hidden labour that remain off-camera; it continues with the encounter of the photographer and a photographed whose control over their own representation is often inexistent; and it persists with the museums, academia, visual media companies and archives that profit from the images.

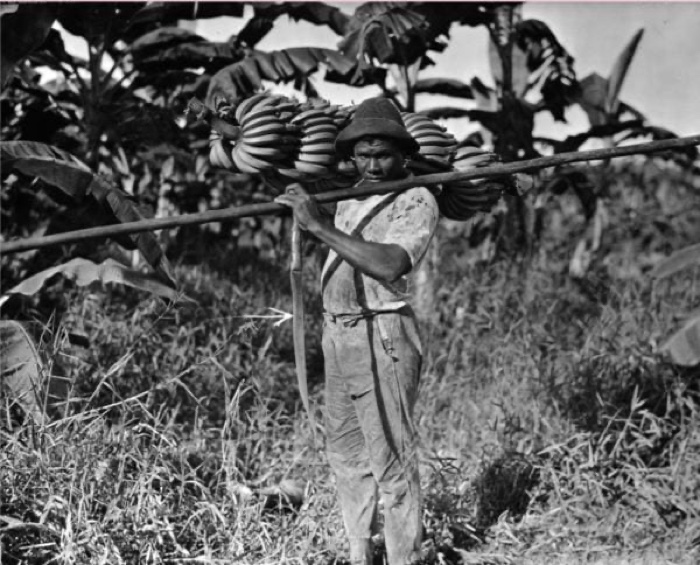

The textbook example of the exploitative dimension of photography is the United Fruit Company (now Chiquita.)

Handling bananas, backing the bunch, Colombia, 1924. Photo: Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School

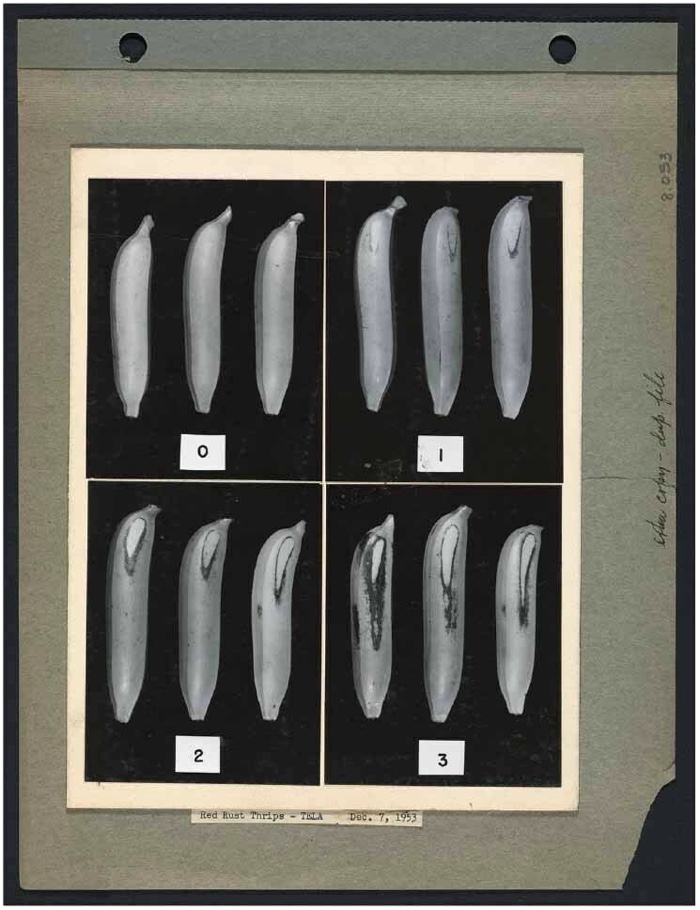

United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Baker Library, Harvard Business

As the extent of the United Fruit Company’s Photograph Collection at Harvard University (around 10,400 pictures) suggests, the camera played a key role in the company’s endeavours. Photography was not only used to advertise the production, it also helped the United Fruit Company present both shareholders and the public with a picture of perfect efficiency, documenting how it controlled nature at a distance, used science to analyse the ripening of bananas and the spread of disease, converted biodiverse forests into monocultures and monitored the productivity of its workers.

Other cases detailed in the book are even more disturbing.

In her essay, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay scrutinises the photographer’s complicity in ruthless practices by using examples such as three photos taken by Burt Glinn in 1956 in Palestine. The original caption “Palestinian Prisoners” adopt the imperial narrative without questioning its authority. These Palestinians, Azoulay notes, are not “prisoners.” They are being brutalised as they attempt to return to their homes or when Israeli occupying forces invade the new homes they were forced to create after expulsion in 1948. She suggests a more honest caption: “Burt Glinn, photos taken in 1956 of Palestinians persecuted by the State of Israel.”

Azoulay extends that complicity to museums, academia and archives whose wealth relies in part on photo collections connected to the exploitation of human beings. A notorious example of this issue is the daguerreotype of Renty Taylor. Forced to pose naked, the enslaved man was used by biologist Louis Agassiz as evidence to support his theory that Black people were biologically inferior. For almost 175 years, Harvard University and its Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology have owned the image. When his descendant Tamara Lanier filled a lawsuit to claim the daguerreotype as a relative rather than the private property of an institution, the judge decided that the legal right to the photos belonged to the photographer, not the subject. Still, Azoulay sees in Lanier’s request “a form of going on strike from imperial photography, a detailed account of unlearning.” Perhaps, one day, this “unilateral right to further abuse those dispossessed with the camera” will be reversible.

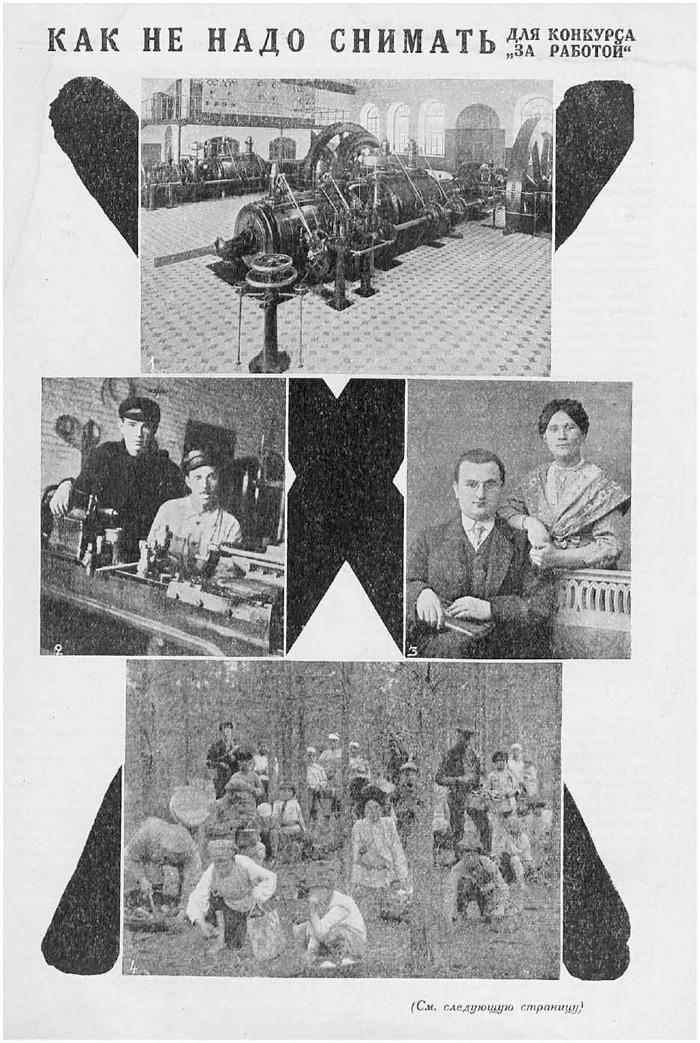

“How Not to Photograph for the Competition ‘At Work’”. Sovetskoe photo, 1927 (via)

Christopher Stolarski‘s text also stands out from the collection of essays. The scholar examines how, in the 1920s and 1930s, the Soviet Union reinvented the camera as an anti-capitalist tool. In the hands of Soviet citizens, the camera was an instrument of transparency, in the hands of capitalists, it was an instrument of opacity. Unsurprisingly, this ideal had to contend with the imperative for photographers to work in line with the dictates of the Communist Party.

Instead of being a medium for authenticity, photography had to adhere to a number of rules. Stolarski mentions the didactic sequence “How Not to Photograph for the Competition ‘At Work’” (January 1927) that defines its aesthetic against Tsarist poses. To portray the workforce transparently, editors were ordered to shoot candid, active images where people engaged with labour, “so that they are all in casual poses and NOT LOOKING AT THE CAMERA.”

The famous Stakhanovite “at work”, the posed portraits of manual labourers and other photo-reportages quickly became an administrative and marketing tool of Stalinism. It valorised the socialist economy by boosting consumer confidence and generating investment in the Communist state.

Edward Burtynsky, Chino Mine, Silver City, NM, 2012

Some of the essays examine the human labour and environmental damages required to transform minerals into boxes, sensors, lenses and other components.

Siobhan Angus, for example, highlights that photography and visual culture would not be possible without massive resource extraction. His thesis invites us to read the photograph as a material object—rather than as a piece of art or a function of technology.

Jacob Emery, however, is more nuanced when he explains that because copper elements of cameras and photographic plates come from mines like the ones depicted in Edward Burtynsky’s aerial panoramas of extraction sites, we can read his photograph not just as an aestheticisation of environmental destruction (an accusation his work often contends with) but as recording both the represented scene and the condition of its representability.

Several essays in Capitalism and the Camera also explore the role that photography could play in constructing and consolidating democratic societies.

An older owner-resident being projected on the ruins. He is among those who resist the developer and demand greater compensation. Photo by Tong Lam

Tong Lam, for example, takes the case of villagers resisting the violence of China’s urban transformation to demonstrate that photography can be used by the subjects being photographed to their own advantage. For the inhabitants of the Xiam Village, who were fighting against the destruction of their homes and way of life, it was important to use images made by themselves and others to counter state narrative and protect fellow villagers. Lam concludes that photographers need to engage the people and places that they are documenting.

I wasn’t convinced by every single essay in the book but I enjoyed their provocation, boldness and their invitation to cast a more critical eye at images. It is not a new idea of course but it reminds us that robust, unflinching media literacy should never be taken for granted. The other meaningful lesson from the book is that photography, in spite of its deep connection with capitalism, remains an important tool to counter capital’s violations of human rights and planetary life.