Inside Private Prisons. An American Dilemma in the Age of Mass Incarceration, by Lauren-Brooke Eisen.

Publisher Columbia University Press writes: When the tough-on-crime politics of the 1980s overcrowded state prisons, private companies saw potential profit in building and operating correctional facilities. Today more than a hundred thousand of the 1.5 million incarcerated Americans are held in private prisons in twenty-nine states and federal corrections. Private prisons are criticized for making money off mass incarceration—to the tune of $5 billion in annual revenue. Based on Lauren-Brooke Eisen’s work as a prosecutor, journalist, and attorney at policy think tanks, Inside Private Prisons blends investigative reportage and quantitative and historical research to analyze privatized corrections in America.

Publisher Columbia University Press writes: When the tough-on-crime politics of the 1980s overcrowded state prisons, private companies saw potential profit in building and operating correctional facilities. Today more than a hundred thousand of the 1.5 million incarcerated Americans are held in private prisons in twenty-nine states and federal corrections. Private prisons are criticized for making money off mass incarceration—to the tune of $5 billion in annual revenue. Based on Lauren-Brooke Eisen’s work as a prosecutor, journalist, and attorney at policy think tanks, Inside Private Prisons blends investigative reportage and quantitative and historical research to analyze privatized corrections in America.

From divestment campaigns to boardrooms to private immigration-detention centers across the Southwest, Eisen examines private prisons through the eyes of inmates, their families, correctional staff, policymakers, activists, Immigration and Customs Enforcement employees, undocumented immigrants, and the executives of America’s largest private prison corporations. (…) Neither an endorsement or a demonization, Inside Private Prisons details the complicated and perverse incentives rooted in the industry, from mandatory bed occupancy to vested interests in mass incarceration. If private prisons are here to stay, how can we fix them? This book is a blueprint for policymakers to reform practices and for concerned citizens to understand our changing carceral landscape.

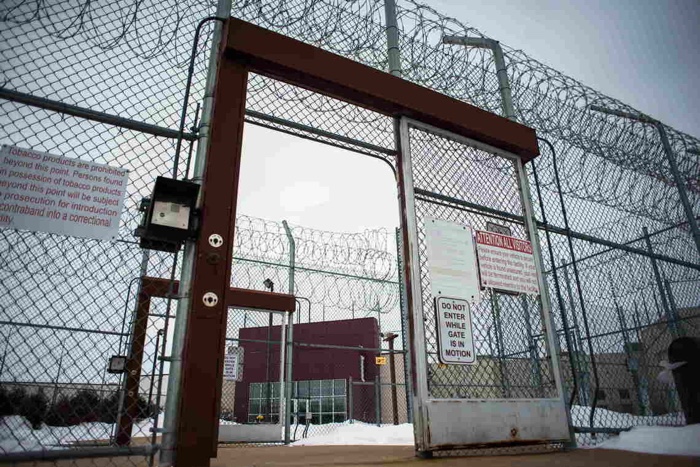

Prairie Correctional Facility in Appleton, Minn. Mark Vancleave/ZUMA. Via the marshall project

I’d never call myself an expert in incarceration but because i follow closely the Prison Photography blog, The Intercept and watch the odd documentary, i’ve known for long that the USA has one of the highest incarceration rates in the world (right after Seychelles apparently.) 693 people out of 100,000 find themselves behind bars. That is nearly five times Britain’s and 15 times Japan’s rate. Because of mass incarceration, the U.S. government is contracting private corporations to house and monitor inmates that cannot find a bed in overcrowded public prisons.

I’ve always been very curious about an industry which financial well-being depends on keeping as many people behind bars as possible and for as long as possible. Lauren-Brooke Eisen‘s book sheds a compassionate, lucid and, she hopes, unprejudiced light onto the private prison industry. I wasn’t planning to review it but i learnt so much throughout the pages that i had to write something about the publication. I’ll start with a few facts and figures gleaned throughout the book:

– Private prisons “house 126,000 people in America, or 7% of state inmates and almost 18% of federal prisoners.” At the end of 2016 more than 40,000 undocumented immigrants were held in immigration detention facilities on any given day;

– between 1984 and 2005, a new prison opened every 8 and a half days;

– According to Adam Gopnik, more people are incarcerated America today than were imprisoned in Stalin’s gulags

– today Afro Americans are incarcerated at nearly 6 times the rate of whites Americans,

– 1 out of 9 state workers is employed in prison and today the country employs more correction officers than pediatricians, judges, court reporters and firefighters combined. Many states spend more in incarceration than they do on education;

– today, the for-profit industry manages 8% of prison beds across country but 62% immigration detention beds;

– 1 in every 28 children has a parent behind bars so children programme Sesame Street recently introduced a new character whose dad is imprisoned:

Alex, Sesame Street’s first-ever muppet with a parent in prison

The first chapters of Inside Private Prisons set the stage by looking at the history of prison in the U.S.A., the rise of the privatization of government services since the early 1800s, the long history of using captive labor for economic purposes, etc. The author then turns her attention to the many forms that the privatisation of the correction sector can adopt: from cigarettes especially designed for use in prison to technology that protects against civilian drones, from correctional trade shows to super lucrative prison telecommunication to enable families to converse over long distances.

JP4, the first tablet designed specifically for prisoners. Photo: Motherboard

A large section of the book also details how private-prison firms are attempting to ‘diversify’ and respond to the recent drive in being “smart on crime” rather than being “though on crime.” Criminal justice reformers are indeed looking for ways to safely reduce prison populations by investing in alternatives, by reforming sentencing laws, by reducing revocations to prison for violating probation or parole, etc. Policy makers have realized that more incarceration didn’t automatically translate into large crime-reduction benefits for the country and that the high rates of recidivism didn’t came about because of an increase in crime or because American citizens are inherently more prone to offend than others but because of policy choices adopted in previous decades.

The private sector is thus looking into ways to get involved into these alternatives to imprisonment and to make a profit out of the endeavours: they build halfway houses, drug or mental health treatment facilities, intermediate sanctions facilities, develop electronic-monitoring services and get involved more closely (and lucratively) into job training and other community-based operations that include rehabilitation. Carl Takei calls this trend ’the Wal-Martification of reentry.” The financial incentive in each of these operations is to keep people trapped in system for as long as possible.

Worryingly, it seems that nowadays, the biggest cash cow for the private prison industry is illegal immigration. Providing beds for immigrant detainees makes a lot of (financial) sense: these people have limited legal rights and are not guaranteed education programs, job training nor mental health and drug abuse counseling. They cost less and complain less.

Unsurprisingly, the election of Trump is a blessing for the whole industry: the new president favours rampant privatization and though on crime policies. And although he is notoriously ‘not racist‘, Trump is very keen on expanding the US immigrant detention infrastructure.

Throughout the book, people interviewed by the author conclude that even though private prisons have existed in US for almost 4 decades, there is still little evidence that they are cost saving and that they provide any substantial benefits for society. They also lack transparency and accountability. In the last chapter of the book, Eisen suggests 10 concrete requirements that would set the ground for a more robust state and federal government contracts with the private industry. But ultimately, she notes, the discussions around private prisons are a diversion from the real discussion about incarceration and punishment. I’ll end with a quote from her book:

The distinction between private and public prisons is not as important as the distinction between warehousing criminals and rehabilitating them.

Inside Private Prisons with Lauren-Brooke Eisen. A talk held at Revolution Books NYC, on 30 November 2017

Previous stories: 13th. Repackaging slavery, Prison Gourmet, YOUprison, Some thoughts on the limitation of space and freedom, Artissima: America’s Family Prison, etc.

Image on the homepage: Women at the Taconic Correctional Facility in Bedford Hills, N.Y., in 2012. Seth Wenig/Associated Press, via.