In 1895, Louis Lumière presented a private demo of what is often called “the first motion picture of cinematographic history”: La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (usually translated in English as Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory.) The 45 second film was shot by Lumière at the photographic factory he owned with his brother Auguste in Lyon-Montplaisir.

Louis Lumière, La Sortie de l’Usine Lumière à Lyon (All 3 Versions), 1895

The pioneering work puts workers, and the factory, at the core of cinematic history. The irony is that you never see the inside of the factory. Nor do you catch a glimpse of the employees at work. The primary aim was to show how the emerging technology captured motion. The workers themselves were little more than props. And because 19th century filming was a much more burdensome affair than now, the film was shot outside of the working hours, which not only highlights the power dynamics between Lumière and his employees but also highlights, right from the get go, the ambiguity of the camera lens.

Images at Work, a show curated by Laura Lux at Casino Luxembourg, takes the Lumière film as the starting point of an investigation into the uneasy liaison between the camera and labour.

The exhibition brings together experimental documentaries and artist films capturing the mechanics, manual routines and poetic experiences of labour in old and new sites of production, while they engage with the history of its representation through the moving image.

The films say very little about labour conditions themselves. Yet, they show how much has changed in the nature of labour, its conditions and its screen representation since the Lumière era. Industrial optimism is gone and the working class has been subjected to processes of globalisation, precarity and invisibilisation of human labour behind automation.

Some of the film shown at Casino de Luxembourg revisit the iconic trope of employees leaving their workplace. Others distance themselves from the mostly white and male blue collar workers and portray other communities as they engage with mechanised, artisanal and other forms of production. This review of the exhibition focuses on the former group of films, the ones that directly reference the Lumière film.

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory © Harun Farocki, 1995

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory © Harun Farocki, 1995

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory © Harun Farocki, 1995

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory © Harun Farocki, 1995

Harun Farocki, Workers Leaving the Factory © Harun Farocki, 1995

100 years after Lumière’s pioneering work, Harun Farocki investigated the history of the cinematographic representation of employer/employee relations. His video essay compiles footage —from feature films by D. W. Griffith, Fritz Lang, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Chaplin to silent newsreels and documentaries- that show workers leaving the workplace.

One of the questions that the artist asks is why processes of labour have so often remained on the fringe of cinema representation. In feature films especially, narratives about individual lives begin once work is over and the anonymous workforce dissolves into separate individuals. The film excerpts use the gates of the factory to signal both enclosure and liberation. They also show how the space in front of the factory gates has often been the scene of social conflicts. That is where strikes, pickets, evictions, and clashes between strikers and the police take place.

In Farocki’s collage, the images bear witness to the rise and fall in importance of industrial labour, declining after the unionised struggles of the 1960s and 1970s.

The film is 36 minutes long and wonderfully watchable.

Ben Russell, Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai) (film still), 2008

Ben Russell, Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai), 2008

Workers Leaving the Factory (Dubai) portrays in one long take the vast difference between labour in the Lumière era and the kind of labour that exists in today’s globalised world. The workers in Russell’s film are construction workers. They appear against the backdrop of half-built skyscrapers and are pointed towards unmarked buses that will probably drive them to a miserable workers’ housing block.

Just like in the era of the Lumière brothers, this is a world of class stratification and it is highly unlikely that they will ever step foot inside these high-rise buildings once they are finished. Unlike the Lumière’s employees however, these workers are all male and their home is far away. Most are migrants from Southeast Asia driven by the forces of global capital to a rich oil country and to “a neo-Fordist architectural production site that manufactures skyscrapers like so many cars.”

Sharon Lockhart, EXIT (Bath Iron Works, July 7-11, 2008, Bath, Maine)

Sharon Lockhart, EXIT (Bath Iron Works, July 7-11, 2008, Bath, Maine) (extract)

In a clear nod to the Lumière film, Sharon Lockhart filmed employees leaving the Bath Iron Works in Maine over the course of five working days in July 2008. This time, however, workers are filmed from the back and time stretches out to 41 minutes, lingering over the repetitive procession of anonymous individuals. Exit captures the temporal and physical “shift” from labour to rest and observes the subtle differences and symmetries that characterise the stodgy routine.

Yet, the workers are regarded as lucky. Their industrial jobs, while remaining the epitome of the “working class” electorate, are increasingly rare in the United States. As a result, the film acquires a vintage patina, it portrays a culture on the brink of extinction.

Andrew Norman Wilson, Workers Leaving the Googleplex, 2011

Andrew Norman Wilson’s Workers Leaving the Googleplex reveals the class system that partitions Google’s employees and the anachronistic caste model behind the supposedly revolutionary company.

In 2007, Wilson was working as a video producer for Google at their headquarters in Mountain View, California. As an employee with a red ID badge, Wilson enjoyed the perks offered by Google: massages, yoga classes, gourmet meals, snacks à gogo. However, he soon noticed that along with the white badges of full-timers, the red badges of contractors, the green badges of the interns, there were yellow badges worn by a class of workers. Mostly Black and Latino, these individuals were denied the privileges that mostly white and Asian employees got access to on the Google campus. Most of them were supposedly involved in the labour of digitising information.

One day, at lunch time, Wilson set up a camera and tripod in a few places around the campus and recorded white, red and green badged employees coming and going. The next day, he filmed the exit of the yellow-badged workers. The day after, he introduced himself to a few of them, saying that he was a colleague and wanted to incorporate their perspectives into the video.

The day after shooting the last video, the film maker was fired.

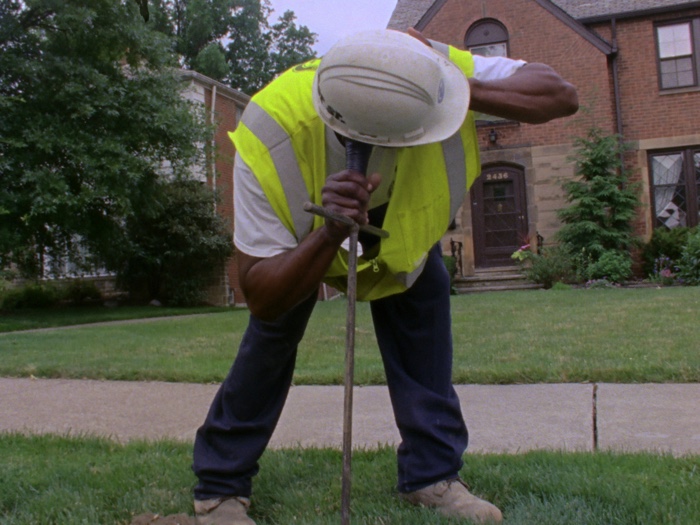

Kevin Jerome Everson, Sound That (production still), 2014

Kevin Jerome Everson, Sound That, 2014

And i’ll end withe a few lines about one of the videos on show that didn’t quote the Lumière film but that highlight gestures, tasks and skills that usually go unnoticed. Kevin Jerome Everson. Sound That portrays Cleveland Water Department employees hunting for underground leaks. The process looks somewhat magical: the mean plant metal rods and listen to what lies beneath. They are workers who make sure that the critical infrastructure that we all take for granted function. Some of them were briefly made visible during the pandemic but they’ve since faded again into the background.

More works from Images at Work:

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Marché Salomon (film still), 2016

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Marché Salomon (film still), 2016

Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, Marché Salomon, 2016

Rehana Zaman, Alternative Economies, 2021

Rehana Zaman, Alternative Economies, 2021

Rehana Zaman, Alternative Economies (excerpt), 2021

Kevin Jerome Everson, The Barrel

Siegfried A. Fruhauf, La Sortie, 1998

Images at Work, vue de l’exposition au Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain. Photo : Lynn Theisen

Morgan Quaintance, Repetitions (film still), 2022

Céline Condorelli & Ben Rivers, After Work, 2022.

Images at Work was curated by Laura Lux. The exhibition remains open at Casino Luxembourg – Forum d’art contemporain until 28 April 2024.

Related stories: On the obsolescence of cognitive and creative labour, Crises of labour, language and behaviour. An interview with Jeremy Hutchison, Indolence and other strategies to resist the 24/7 work culture, The Chronocyclegraph, Capitalism and the Camera. Essays on Photography and Extraction, An exhibition about labour: can we still want it all?, etc.