A School of School, the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial, closed two weeks ago and i’m still struggling to type down the final notes from my visit to the event. The past few weeks have been exhausting and exciting but the end of the tunnel is near! I’m really happy to sit down today and write about the work of Ebru Kurbak, a (super talented) Turkish artist and designer based in Vienna. She was showing three very strong projects in Istanbul. Each of them reflects her interest in the often invisible political nature of spaces and technologies, and in the way the design of the ordinary can help shape values, practices and ideologies.

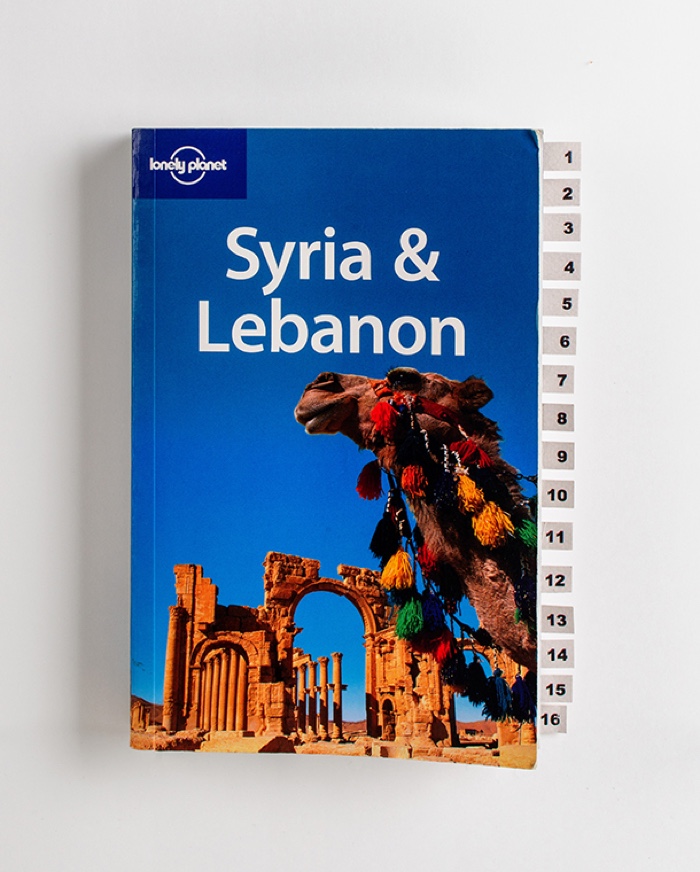

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet. Photograph by Kramar/Kollektiv Fischka

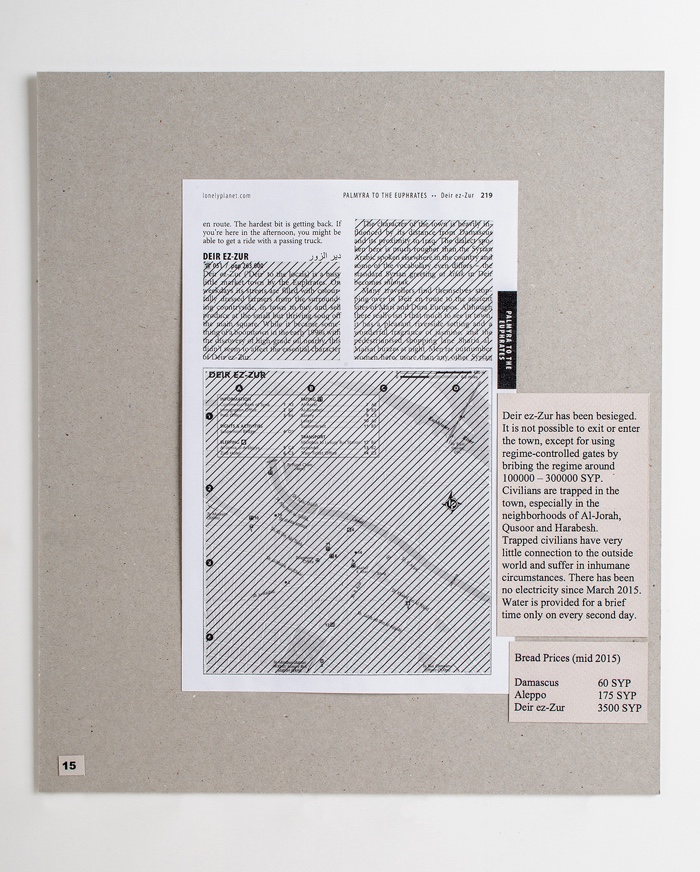

Lonely Planet was the work that moved me the most. This version of the touristic guide of Syria was revised and annotated not by savvy globetrotters but by the people who had lived there and had just fled the country. The result is a poignant overlay of landmarks that have been reduced to rubble, routes that can no longer be taken safely but also everyday realities that survive in some form or another despite the hardship. The work, under its unassuming aesthetics, brings nuances to a country that has, in the eyes of most foreigners, transformed from being “one of the most peaceful exotic travel destinations” to “one of the most dangerous places on the planet”.

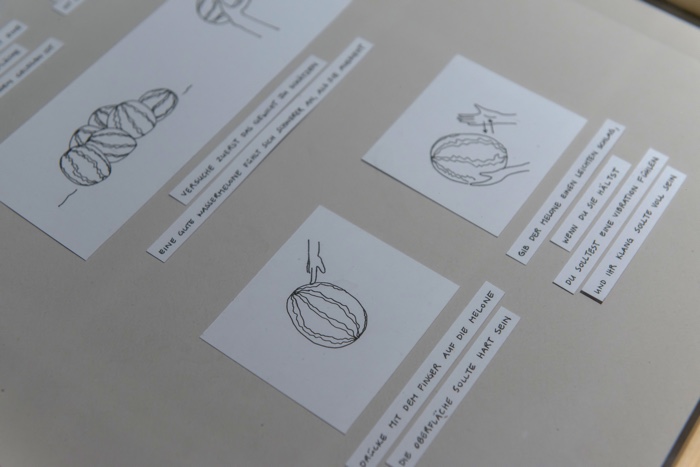

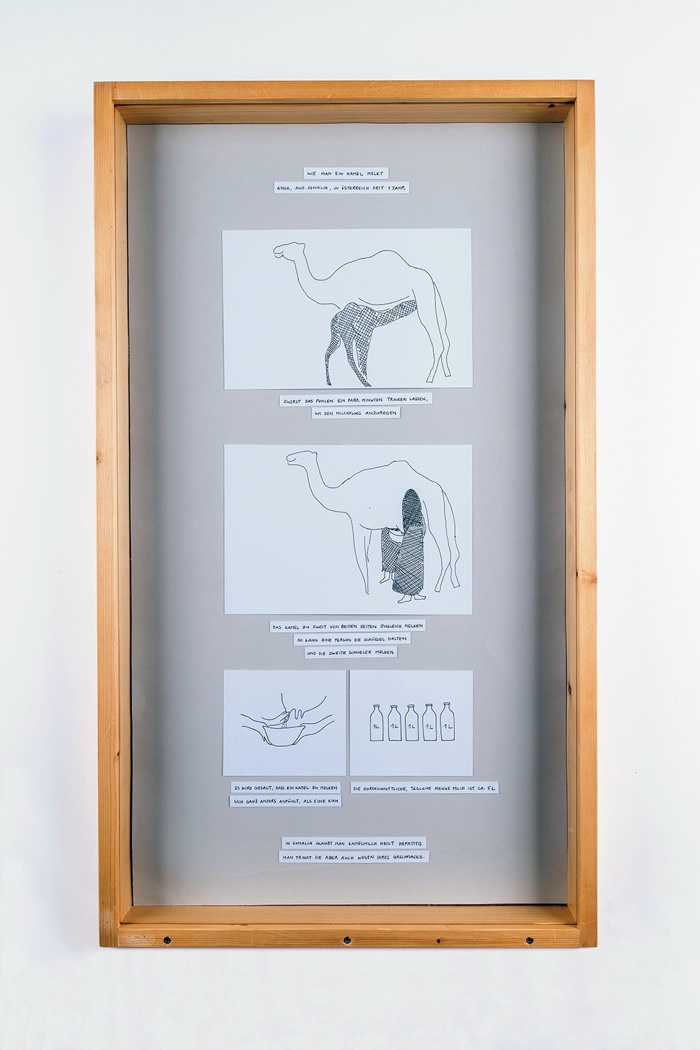

The artist and designer has also worked with migrants to create Infrequently Asked Questions, a series of workshops in which she asked just one question to people who had recently arrived in Austria, could barely speak German and had lost some self-confidence in front of all the new knowledge and skills they had to learn in order to get by in the new country: What are you good at? The work reveals the best way to milk a camel but also the fact that the values of things are social constructs, not absolute facts.

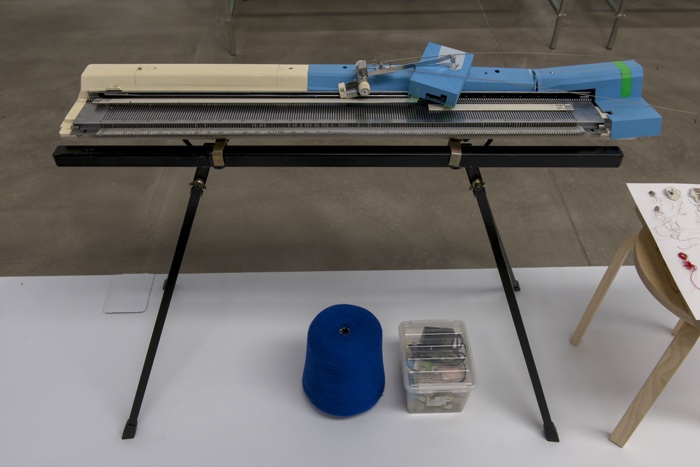

So Kanno and Ebru Kurbak, Yarn Recorder (Stitching Worlds), 2018. Photograph by Elodie Grethen ©Stitching Worlds

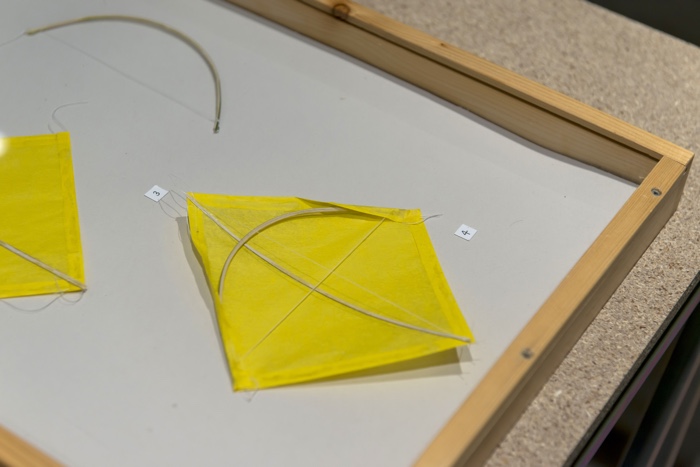

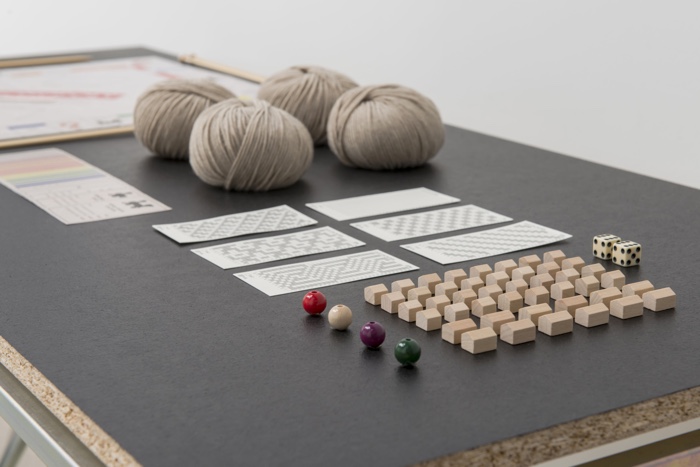

Finally, the biennial also presented Stitching Worlds, an investigation into how different technology would be if textile craftspeople were the catalyst to its industry. The collaborative project produced devices as diverse as a magnificent embroidered computer, an instrument that utilizes spools of yarns and threads to record and play sound, a board game that reflects on cryptocurrencies by requiring players to knit the money they need or a sweater that gives its wearer the ability to occupy electronic space by sending invisible radio transmission waves.

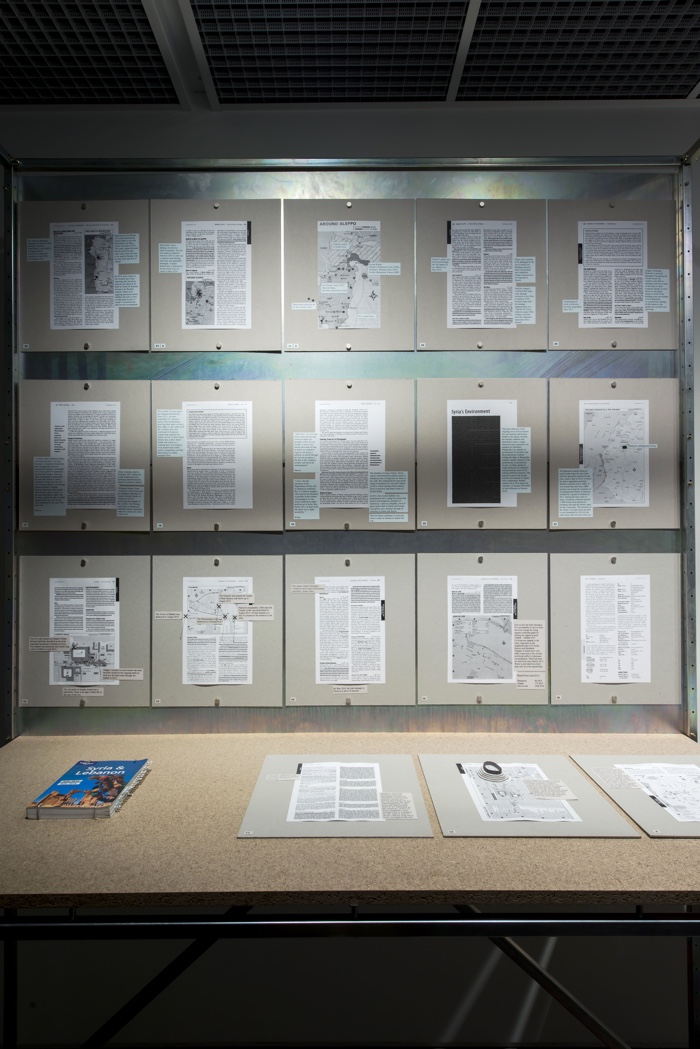

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet. Photograph by Kramar/Kollektiv Fischka

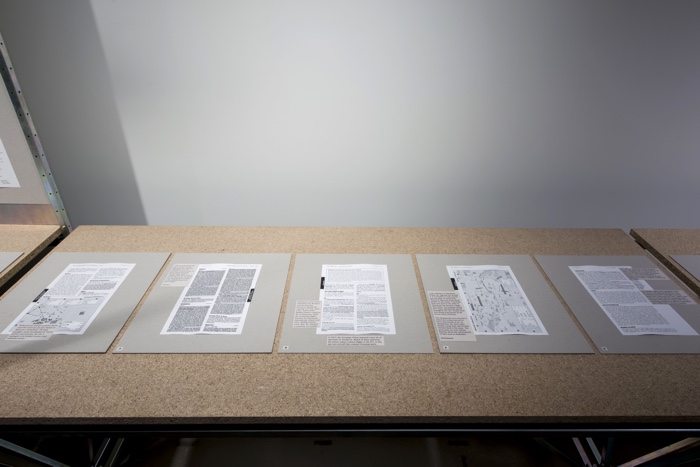

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet, exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

I talked with the artist shortly after my return from Turkey:

Hi Ebru! Your work Lonely Planet attempts to understand the present reality in Syria by editing a travel guide through interviews with people who recently fled from the country. How did you get the idea for this work? Did the initial idea emerge from discussions with people who have moved from Syria to Austria?

The initial idea actually emerged before I met the people. Back in 2016, the University of Applied Arts Vienna had dedicated one of their vacated buildings as temporary a shelter for people who just arrived from Syria. I was working there at the time when over a thousand people started residing in the building neighboring my workspace. When the University decided to put together an exhibition on this subject, the curator Işın Önol asked me whether I would contribute with a new participatory work. The idea for Lonely Planet was one of the few ideas I came up with early in the process and discussed with Işın before I set foot at the shelter.

I think the questions this work asks have a lot to do with my own experiences growing up. I grew up in Turkey receiving constant news about the Iran-Iraq war in the 80s and the Gulf war in the 90s. These were the “officially declared wars,” so to say. But, although not always recognized as such, there have always been conflicts in Turkey as well, and fragments of what one can easily call war.

“War” or “no war” is not always something that changes from one day to another, as the tourist guides depict. There is some daily life that continues, even if the amount might fluctuate over time. But, apart from the official declarations, when exactly do individuals acknowledge that they are in war? The research I did for the work was an attempt to understand how people in Syria experienced this merged reality of ordinary life and war. People that fled from the country must have identified critical moments, which made them take that difficult decision.

The tourist gaze implied with the travel guide also relates to the shame and sorrow I felt about not having been to Syria before and about how surprisingly little I had known about the country. The process taught me a lot of things that I wish I had known and seen before.

But then again, as said, editing a travel guide was only one of the few vague ideas I had in mind. As soon as I started talking to people at the shelter, they made it clear for me that this was going to be it. The people had just arrived to Austria and were eager to talk about where they used to live, how they used to live, what happened and what changed, as much as I was eager to listen. The guidebook gave us an objective framework to start from and our conversations flew smoothly and naturally from there. This made working on this particular idea more interesting for all of us.

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet, exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak, Lonely Planet, exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

How was the whole re-writing process of the guide like? I suspect it must have been a very emotional experience. Is what we can see/read at the biennial in Istanbul and on your website the result of long debates and discussions? Or did the participants all agree on what had changed and how in Syria?

It was emotional. Especially editing the first pages in May 2016. And, it was not only because we talked about painful things. It was a time when everything was very recent and all of us were in some sort of shock or even disbelief. I remember Mohammed, one of the people who helped me the most, pointing at the map in the guide and showing me where he had last parked his car some days ago. And I remember unthinkingly asking him what was going to happen with the car, and waking up with the fact that he did not seem to care. It was hard to grasp that people had truly left things behind—both physically and mentally. Seemingly casual things like that proved the immediacy and reality of everything.

The edits in the pages are results of long talks. But, there was no agreement sought among participants. I spoke with everyone in private, at separate times and places, as people were still quite worried about their opinions to be openly known by others in the shelter. All came from different places and had fought for different political views. Their experiences were different from each other and they relied on different sources for news. So, the work captures rather a collection of multiple realities than one objective truth.

The project relies more on text than on shock images, its immediate visual appeal is thus not obvious. Yet the ability of your Lonely Planet work to convey the shock of what Syria was before and what it is now is very powerful. More perhaps than the newspaper photos we got so used to. Was it something you realised right from the start? Did you know that this subtle and visually unspectacular strategy would be so impactful? Or have you, at any point, been tempted to add photos and colourful graphics to the work?

Thanks so much for this comment. I found it a very difficult task to work with such an emotional topic. A tragedy that involves millions of people in first person… I got terrified of unintentionally creating an inappropriate spectacle. No, I did not ever consider using imagery or graphics. But, I had not planned the calm aesthetics to add an extra impact either. It was my intuitions that brought the work to this point, which, luckily, I still feel comfortable with.

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. How to cook Ashak, by Zarifa.Photograph by Marcell Nimführ/Kollektiv Fischka for Vienna Design Week

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. How to build an Aqal, by Amina

The project Infrequently Asked Questions (iFAQ) reflects your own experience as an immigrant. When you arrived in Austria from Turkey, you had the feeling that the skills you had gathered while growing up in Turkey had no value in your new country. What were these skills exactly? And conversely, are there skills you learnt in Austria that are useless to you when you go to Turkey?

There are many practical examples that come to my mind, such as coping with snow in winter, or, riding a bike in the city. But, frankly, the most difficult skills I had to learn were about human relations. “Wiener Schmäh,” the local and slightly insulting sense of humor referred to as the “Viennese Charm” was exceptionally difficult to get for me, for instance. Before I moved to Austria, I had not realized how much I was influenced by the Anatolian culture. And there is indeed a huge difference between the two cultures in terms of how people generally relate to and communicate with each other. It took me a while until I could recognize how hard-coded my own assumptions and expectations were, particularly about personal relationships. This was an eye-opening experience. But, it was and still is a challenge to tune those assumptions down. I guess this is a pretty common feeling among people who migrate to cultures that are unlike their own. It takes many unnecessary disappointments until one is able to read some of the intentions behind unfamiliar gestures. The skills I learnt here are not as useless when I go back to Turkey though. They might not be useful literally, but they help me identify our unquestioned habits in Turkey and look at them critically.

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Photograph by Kramar/Kollektiv Fischka

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz. Photograph by Kramar/Kollektiv Fischka

Some of these skills and knowledge shared in iFAQ are indeed not very useful in Europe. How to milk a camel for example. Others are. How to recognise a good watermelon for example. I also like the turmeric face mask. What did the experience of working on this project with you brought to the participants? Did they emerge with more self-esteem? A better idea of who they are? A greater understanding of how different cultures can be from one another?

I wanted to highlight that having to learn new skills at a new home does not necessarily mean one is unskilled or undereducated in general. It just means that they had to spend their lives acquiring a totally different set of skills. So, actually, I tried to excavate and display the least useful skills to make my point clear. Later on, when I exhibited the work, I did notice many visitors taking a picture of the watermelon one in particular, saying how useful that information was!

Yet, for me, the work is neither about learning from newcomers, nor about repurposing skills and finding new ways for them to provide for their families.

I intended the work to address the local audience and decision makers more than the participants. I wanted to intervene in the widespread perceptions about the situation. But, the process did also bring us all to a greater understanding of how different cultures can be. The participants were very surprised and entertained by what knowledge and skills I found exciting. Also, in scope of the Vienna Design Week, I organized workshops taught by the migrant women. Local people from Vienna could register for the workshops and learn new skills.

The immigrant women told me they really enjoyed those workshops. It was a totally different social experience for them in which they interacted with local people on a different basis than they are able to do in their ordinary lives.

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Did you work only with women? And if yes, why?

Yes, but not exclusively. The Vienna Design Week had commissioned this project and linked me to the Caritas Lernsprung adult education program as partner. I ended up working mostly with women because it was mostly immigrant women who went through a long and exhaustive voluntary education process at the Caritas Lernsprung. The courses were in fact open for men as well. But when I asked why there were no men around, I was told that men were not as open as women to visiting classes at older ages. At the time of my visits, there were two classes of women, one class from Somalia and one class from Afghanistan, who first were going to learn how to read and write in their own languages. Then, they were going to continue the courses by learning German. After that there comes information about basic necessities of daily life such as way-finding in the subway or being able to use a cash machine. The biggest motivation for the women I met was them wanting to support their children at school. There are a few skills in the exhibition that were collected from men, whom I interviewed during the project but at other places than the classes.

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

If I understood correctly, the opening question for the workshops was “what are you good at?” I find it incredibly difficult to answer that one myself. Was it obvious for the participants to pinpoint what they were good at?

No, not at all! It took us quite some time before the process really started rolling. The first time I visited the class I was welcomed with amazing local food the women had prepared and brought with them. They also had brought a few beautifully handcrafted objects and laid them on their desks. I was extremely surprised and humbled by this gesture. Apparently, their teacher had told them that they would get a visitor and explained roughly what I was up to. The next time I visited, I cooked a pot of stuffed vine leaves based on a recipe from my hometown and brought it to them. Instead of bringing handcrafted objects, I shared examples about the most mundane knowledge and skills I could think of. For example, I gave them a recipe for home made hair removal wax, which was common knowledge among Turkish women during my childhood. Such mundane examples helped us move our focus off food and handcrafts onto more daily knowledge and skills. I asked them what daily skills I would have to learn if I moved to their village. They started coming up with the most amazing ideas on what to teach me.

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak, Infrequently Asked Questions, 2015-2016. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

I liked the way you present the participants’ contributions. They are delicately framed like valuable artefacts. What is the motivation behind the particular way in which you present these skills?

Most of the visualizations and objects in those frames had been created in the process of collecting the skills. The participants and I did not really have a common language to speak. Their teachers helped us translate things but we mostly had to speak in broken German. I made models and drawings to help us communicate more precisely about the skills. I kept all those materials that were created during the interviews and later on integrated them in the instructional frames I designed. The instructions include plenty of visual information besides German texts because I wanted the participants to be able to follow and understand them as much as the local visitors of the exhibition were. When the participants saw the frames, they were able to identify which frame depicted the skill they personally taught me and check the accuracy of what I had gathered from our conversations.

I’d also love an iFAQ book in which you’d gather some of the skills and knowledge collected during these workshops. Have you thought about it?

Yes. With this work I received the Erste Bank MoreValue Design Prize, which came with a project budget for the designers to continue the work in the way they want. An iFAQs book was one of the ideas I had when I was pondering on how I would like to continue. In the end, I decided to rather expand the scale of the project first with more skills and exhibit it a year later. The exhibition took place at the Austrian Museum of Folk Life and Folk Art, which has a quite local visitor profile that was amazing to reach. We also created a small catalogue on the whole project, together with Vienna Design Week, Erste Bank and Caritas. The booklet includes some of the collected skills, but also articles on the topic and process, and interviews with the participants. The idea about an iFAQs skill-book is somehow stuck in my mind. I am still collecting skills as I come across them and might pick up on that book idea in the future.

Ebru Kurbak and Irene Posch, The Embroidered Computer (Stitching Worlds), 2018. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak and Irene Posch, The Embroidered Computer (Stitching Worlds), 2018. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak, Stitching Worlds, 2018. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

Ebru Kurbak, The Knitcoin Edition (Stitching Worlds), 2018. Exhibition view at the Istanbul Design Biennial. Photo: Kayhan Kaygusuz

What’s next for you? Any upcoming projects, events, fields of research you’d like to share with us?

Well, there are a few commissioned exhibition projects I am running in parallel. But, I have been mostly busy with wrapping up another long-term and large-scale artistic research project titled Stitching Worlds. The project questions the politics of invention in terms of how it influenced societal evaluation of skills. We looked at textile crafting techniques as alternative ways to create electronic technologies and spent about four years on making technological research in the marginalized space of often-undervalued women’s work. The project recently ended with an exhibition and a book, but also opened up a few new exciting research topics that I’m currently looking into. I’m very curious to see where those ideas will lead me to!

Thanks Ebru!

Ebru Kurbak’s projects Lonely Planet, Infrequently Asked Questions and Stitching Worlds were part of A School of School, the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial, curated by Jan Boelen and organised by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV). The exhibitions closed on 4 November 2018.

Also part of the biennial: Staying Alive. A “wunderkammer” of disaster solutions, Halletmek. The Turkish art of speeding up design processes and Genetically Modified Generation (Designer Babies).