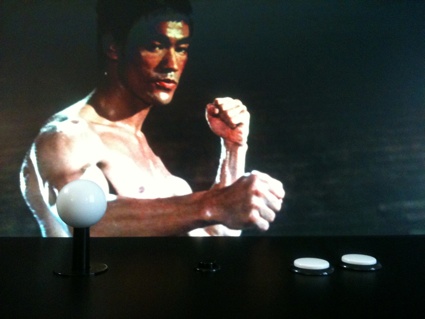

Still from Hold On, The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Still from Hold On, The Shining (Stanley Kubrick, 1980)

Installation view of Hold On at Festival Gamerz, Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en-Provence,2012. Photo courtesy EBMM

Installation view of Hold On at Festival Gamerz, Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en-Provence,2012. Photo courtesy EBMM

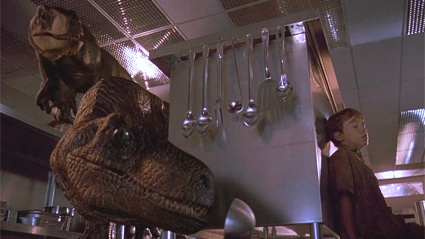

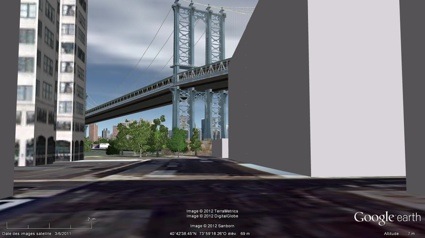

One of the best surprises of this year’s edition of the GAMERZ festival in Aix en Provence was a work that mixed clips from cult movies with video game dynamics. Using 2 buttons and a joystick, visitors could navigate inside movie sequences from The Shining, Jurassic Park, The Blair Witch Project, Old Boy and many more. The main actor becomes an avatar and you can delay the inescapable moment when the little boy in The Shining bumps into the evil-looking twins or you can give a couple of extra kicks and lengthen the fight that opposed Bruce Lee to Chuck Norris in Way of the Dragon.

Hold On, by Maxime Marion & Emilie Brout is pretty irresistible. You want to try all the movie sequences and then you want to try them once again to see how much more you can do inside the same movie clip.

There’s no video to demonstrate how the installation work. Not yet. In the meantime, i’ve asked the artists Maxime Marion & Emilie Brout to take us behind the scenes of their project:

Bonjour Emilie and Maxime! How did you chose the film sequences? Does any action movie work for example? What were you looking for exactly when selecting the extracts?

The idea behind Hold On is very simple, but its efficiency depends heavily on the choice of sequences, which proved to be more complicated than we initially thought! Many constraints have to be respected. For example, you need a main character at the center of the action so that he or she can immediately be identified as avatar. You also need homogeneous settings, lest you get shocking discrepancies as you move around. We are also looking for autonomous extracts, with an introduction, a conclusion and an issue to solve. There are many extracts we would have liked to use but we had to leave them aside because they wouldn’t work.

More generally, we’ve been looking for film sequences that have their own originality, often referring to famous video game genres, like in The Shining where the little Danny irresistibly evoques Mario Kart, or the puzzles that the dung beetle needs to solve in Microcosmos which evokes games such as Worms or Lemmings. We’ve made some 15 sequences so far, but for Gamerz we left aside the ones that didn’t fit this year’s theme. We will show Travolta’s incredible danse in Saturday Night Fever another time.

Still from Hold On, Microcosmos (Claude Nuridsany & Marie Perennou, 1996)

Still from Hold On, Microcosmos (Claude Nuridsany & Marie Perennou, 1996)

Still from Hold On, Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

Still from Hold On, Jurassic Park (Steven Spielberg, 1993)

It was amusing to watch people play with Hold On at GAMERZ. Some had reactions of surprise and tension because instead of diluting the suspense, the installation often increased it. Is this something you were expecting?

Indeed, the visitors’ reactions far exceeded our expectations. It was great for us to witness it. When people are allowed to navigate inside a movie, they have a feeling of freedom, of broader space and abolished temporality. Paradoxically, by losing these limitations of the views, you find yourself in a kind of maze, in a scary labyrinth.

The sensation is enhanced by the fact that it is far more engaging to embody an avatar than to just watch an actor on the screen, and we often know what to expect at the end. That’s another reason why we chose very famous movies. When you stop playing, the film simply proceeds till its -not alway happy- ending. Some people were thus playing as long as possible in order to delay the unescapable death in the final scene of The Blair Witch Project, or to avoid meeting the little girls of The Shining, which might occur after each turn in the corridors.

We are also happy to have been able to reproduce faithfully classic game controls, such as in the fight between Bruce Lee and Chuck Norris in The Way of the Dragon, its game play is identical to the Street Fighter 1: we’ve seen some pretty enthusiastic otakus. And seeing how much fun people were having, sharing with them this fantasy of ‘getting inside’ a movie was probably what mattered the most.

Installation view of Hold On at Gamerz, Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en-Provence,2012. Photo by Luce Moreau

Installation view of Hold On at Gamerz, Fondation Vasarely, Aix-en-Provence,2012. Photo by Luce Moreau

You developed the work Hold On during a residency with M2F Creations in Aix-en-Provence. Can you tell us something about the residency? What you found there, how it went on?

We first had the idea of the project in 2006 and its form has evolved ever since, but we needed an impuse to make it come into existence. That’s exactly what M2F Créations gave us. We also needed some technical support, especially regarding the responsiveness of the HD video that had to react under 40 ms, plus some electronics for the interface.

So last May we were invited to the Maison Numérique, which Quentin Destieu & Sylvain Huguet are developing more and more. While we benefited from the invaluable technical skills of artists such as Stéphane Kyles and Grégoire Lauvin, we also found that the residency provided us with a fantastic space for exchange and sharing where we’ve built long lasting relationships. We particularly enjoyed M2F’s innovative approach which enables experimental practice while fostering research. In a nutshell, this is a residency we highly recommend!

Still from GEM, Fellini’s Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972)

Still from GEM, Fellini’s Roma (Federico Fellini, 1972)

Still from GEM, Once upon a time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984)

Still from GEM, Once upon a time in America (Sergio Leone, 1984)

Most of your other works show how fascinated you are by cinema. I particularly like Google Earth Movies. What did you learn from this transposition of cult movie sequences into the Google Earth software?

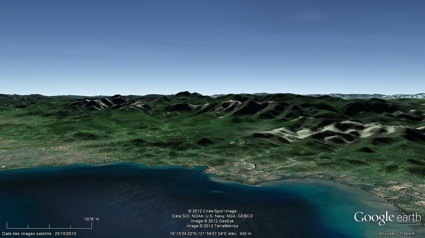

Cinema plays indeed an important part in our works. The concept of GEM is to transform a mapping tool into a filmic object, to use Google Earth as if it were VLC. The software allows you to manage many factors when you enter the code, such as tilting, or the focus that enabled us to recreate the famous Jaws Shot.

Google Earth Movies – Jaws (beach panic scene with vertigo effect)

As we were trying to reproduce as faithfully as possible inside Google Earth the movements of the cameras on the real shooting locations, we realized how complex and subtle these movements can be. It was a real lesson of cinema. For example, we recreated the scene of the death of Dominic in Once Upon a Time in America. As the child falls after the shot, the camera follows him, gently going down. Then, as he dies, the camera goes up, a metaphor for “ascending to heaven.” So although there is no visible character in GEM, you understand the whole action. In Apocalypse Now, you almost see the helicopters performing their massacre.

Still from GEM, Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

Still from GEM, Apocalypse Now (Francis Ford Coppola, 1979)

While adjusting the light, determining the year, the month and the time with an accuracy of 5 minutes in some cases, we also realized that some scenes that seemed to follow each other perfectly had been shot at different moments (because of the quality of the light.) But this only serves to reproduce a cinematographic feeling for viewers who can discover by themselves the off-screen landscape by turning the camera around.

Still from Dérives, La Piscine (Jacques Deray, 1969)

Still from Dérives, La Piscine (Jacques Deray, 1969)

Hold On, as you wrote in the presentation text, does the opposite of a machinima, it uses cinema for gaming purposes. But would you use games to make a film? I’m not talking about machinimas but about a film, experimental or not, that would use the dynamics of a game or its interactivity? Is this something that already exists or that you are planning to do at some point?

This is an angle that interests us but it is also different from what we do because it entails some real directing work. Our approach involves the use of found footage, and remaining in reality which triggers so much fascination, rather than in purely synthetic images. At the beginning of Hold On, we had worked on Rashomon by Akira Kurosawa, which tells the same story under four different perspectives. We wanted to make a kind of total movie/game that would allow you to create your own story. But the result was too complex to use. The current version is far more efficient because the simplicity of the controls does not disturb the immersion of the player (a big problem with interactive films) and that is what matters.

But it is true that we are very interested in the dynamic aspect. The work Dérives, for example, uses more than 1500 film clips that represent water and, by constantly renewing the editing, it generates a kind of infinite meta-film. Dérives is not interactive but it is dynamic and generative so it’s not cinema anymore. It is almost impossible to cover it all. There’s still a lot to do with captured images and generative effects.

Merci Emilie et Maxime!

The festival GAMERZ is over alas! but Google Earth Movies is currently part of the show UPLOLOLOAD – In praise of a diminished reality in Paris.