Artist and cultural anthropologist Leone Contini has been collecting seeds for over 10 years. Preferably seeds that were given to him by members of the foreign communities who have migrated to Italy in recents years, bringing with them seeds to grow familiar fruits and vegetables on unfamiliar land.

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers, 2018. Photo by Can Aksan

For the Manifesta biennial in Palermo back in 2018, Contini collaborated with migrant communities to plant the cucuzza (a type of pale, ultra long gourd sometimes nicknamed Serpent of Sicily) as well as similar types of squash that had traveled as seeds in the pockets of migrants from African and Asian countries. They grew together on a pergola in Palermo’s Botanical Garden. The work would be little more than an edible metaphor for harmonious coexistence if it didn’t allow for discussions about local food resilience in the face of the climate crisis.

One of the most interesting things that emerge from Contini’s work is that freshly arrived farmers have to revise their know-how and adapt it to the local climate and soil. They become pioneers of “displaced” and confused agriculture. Their resourcefulness and the knowledge they accumulate with each experiment might even turn useful to Italian farmers. As Contini notes, traditional local farming is challenged by an environment in constant mutation: unseasonable weather, soil erosion and other disruptions have turned local farmers into migrants onto their own land.

Leone Contini, Hǎocài, Carmignano, 2015

Leone Contini, 2009-2019

The artist’s interest in food and agricultural practices is rooted in long-term fieldwork across Italy. His inquest started when he moved to Prato, a city in Tuscany which hosts the second largest Chinese immigrant population in Italy. The majority of Chinese people in Prato work in the textile and fashion industry. During the financial crisis, a number of them started growing their own food, planting seeds from China and enriching the “biodiversity” of culinary ingredients available in the area. Having spent time with the Chinese farmers in Tuscany, the artist met other communities who use their spare time to grow food: the Senegalese gardeners in Veneto, the Bengali farmers living at the outskirts of Palermo, etc.

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers – Cucuzze a mare, 2018

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers – Translations, 2018

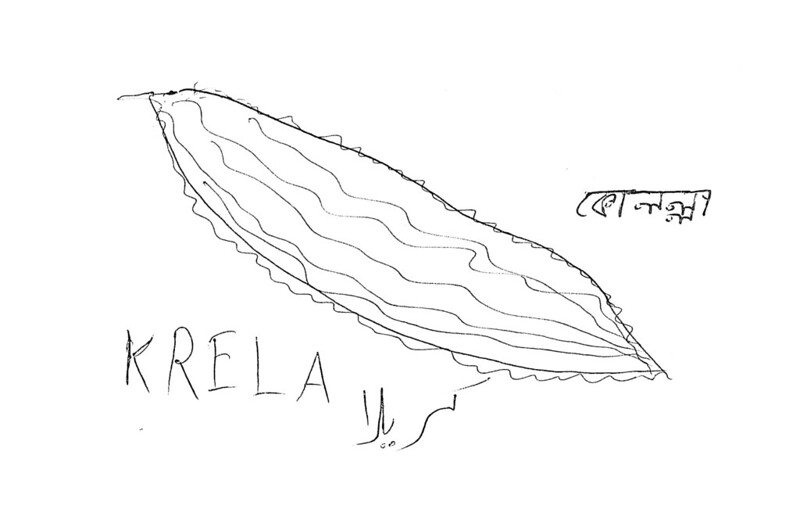

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers – Krela, 2018

Contini’s work makes it clear that seeds, plants, cultures, animals and people that migrate towards new lands are not threats to local ecosystems, they can also offer solutions to the challenges that await our planet, a planet that looks increasingly alien to its own inhabitants.

I interviewed the artist and anthropologist over email:

Hi Leone! You studied Philosophy and Cultural Anthropology at Università degli Studi di Siena. How much of your background as an anthropologist do you bring into your projects?

Of course my artistic practice is shaped by my background but I try to avoid the “discourse about the other”, the original sin of anthropology. Nevertheless this is also a concern of many anthropologists since cultural studies have finally deconstructed the colonial pillars of the discipline. Maybe I can rephrase my answer by saying that my practice takes place on the crossroad between art and anthropology, but faraway from both the academic shelter and the art market.

Moreover, the post (?) covid immobility revealed to me that I feel more (and more) comfortable here, in my neighbourhood, instead of working abroad, “in residency”, like I often did in the last 10 years. Maybe it’s because here I cannot escape the responsibility of representation, I cannot run away with the stories of the people in my pocket, as (we) artists-in-residency tend to do when, the day after the final exhibition-presentation, we jump on the first airplane toward the next site. This hectic appropriation is a consistent mode of production of contemporary art nowadays, a behaviour that seems rooted in the ethnographic practice – although ethnographers usually appropriate with less rush. We are all trapped in the same big game (unless we produce artefacts buried in a studio to be sold in galleries, then maybe we are part of another game), but how to inhabit this pattern is our challenge as cultural producers.

But as I said, for now I’m happy to work in my region-neighbourhood… “locals” and “migrants”, “us” and “them”… all these terms tend to lose their meaning, since here we are all part of the same, variegated community. No “informants” anymore, just neighbours.

Folclore Tosco-Cinese / TuscanChinese Folklore, 2013

Folclore Tosco-Cinese / TuscanChinese Folklore, 2013

You’ve spent several years interacting with the Chinese community in Prato. Your work explores how much these families of migrants have transformed local agriculture. Could you give us a few examples of these transformations?

Local agriculture was transformed in terms of a huge injection of new varieties, and this is important and desirable, at least in my perception, after a century marked by a constant erosion of biodiversity. Even though I don’t live in a cosmopolitan city I can access a wide range of vegetables from different origins, at a convenient price. My food choices at least doubled in the last 10 years, thanks to the Chinese farms.

In the long term this biodiversity will also transform the Italian cuisine, but so far the Italians are reluctant to try new vegetables, and if they approach them, it is only occasionally, out of a curiosity for the “exotic.”

While we, Italians, struggle around the topic of cultural mutations, these agricultural activities have already transformed the distribution chain, making it very short and directly connected with the territory: an “Italian” tomato on a supermarket’s shelf travelled hundreds of km after having probably been collected by an exploited worker in Apulia, while a dōng guā or any other “Chinese” vegetable was grown locally, in a family-based farm.

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers – Germinability, 2018

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers – Harvest, 2018

Leone Contini, TuscanChina, 2015

You write in the description of your work Km0: “Within the context of the Chinese Diaspora these gardening practices are crucial in terms of cultural identity, belonging and self-representation, the regional wenzhounese vegetable varieties being a sort of umbilical cord with the motherland.” I was very moved by that sentence because I grew up in Liège (Belgium) where there is a big community of families whose roots are in Italy. When their grand-parents arrived, they brought herbs, veggies, cheese, all sorts of knowledge about wild mushrooms and good coffee that must have looked very suspicious to Belgians back in the 1950s. Indeed there were tensions and unpleasant moments at the time but that seems to be so long ago now. Belgium recently had a Prime Minister (Elio di Rupo) whose father was from Abruzzo. So I see parallels between them and the communities that your projects talk about but am I a bit naive here? Are there limits to making these optimistic comparisons?

You are not naïve, on the contrary! My mother’s family is originally from Sicily, and in the 80s we used to grow Sicilian vegetables in the outskirt of Florence. Especially the “cucuzza”, a snake-shaped bottle gourd, unknown in Tuscany. By coincidence the owner of the first Chinese restaurant in town (the Chinese migration was still a small phenomenon) had a little garden near our cucuzzas: he cultivated Chinese cabbages and spring onions. All over around us the black Tuscan cabbage was ruling the fields.

When in the 2000s the first Chinese farms appeared on the plain between Florence and Prato… I think I “recognized” this bio-diversity as an archetype of my childhood. And I vividly remember when, for the first time after 20 years, I saw again a cucuzza, that I still regarded as strictly Sicilian: it was on the shelf of a Chinese shop, named pú guā, in Wenzhounese dialect, and as delicious as in my memories.

Thanks to Chinese farmers a dormant family tradition was therefore reactivated, and the trap of “otherness” defused. Like for the urban gardens of Villeurbanne (France), Solothurn (Switzerland) and Folkestone (UK), where I recently developed my projects, here the Sicilian snake cohabits with bottle gourds from Indochina (I was surprised by the use of this term), bitter melons from Nepal or Turkey, okra from Senegal… I feel comfortable in such places, where different origins interweave and prosper.

For a performance at Centro Pecci in Prato, you involved directly the Chinese community, transforming Chinese farmers into advisors for Italian people. Could you tell us how you got them on board and what happened during the performance?

The exhibition was financially supported by the Chinese Buddhist temple of Prato.

My project consisted in a display of Chinese vegetables, a sort of baroque natura morta, the mise en scène of an unknown local treasure of biodiversity. Among the audience many people were from the Temple, I was familiar with some of them. The Museum, as an institutional location, was answering their expectation to be recognised as part of the social fabric, and the beautiful vegetables were something to be proud of. These factors, I think (but we should ask them!), created a bond between them and my installation, aesthetically and emotionally, until the very moment when they appropriated it. It was unplanned! And what happened exceeded my most optimistic expectations: they started distributing the vegetables to the audience, explaining how to process and cook them, but also what their healthy properties were.

Leone Contini, Foreign Farmers, Workshop, 2018

Your practice is also looking at the circulation and exchange of seeds between countries from all over the world. Is there any official regulation around the importation of seeds from abroad? Can people plant whatever they want wherever they want?

Italy is a strange country, we accept the role played by organised crime in the food production and the exploitation of migrant labour, but if a Chinese family creates a little farm to fulfil the local demand… then all the rules are back, to be respected.

The repression of Chinese agricultural enterprises is a recurrent phenomenon in Tuscany, often resulting if the confiscation of the farms.

The irony of such policies is that, in an abandoned field, the plants can often manage to accomplish their reproductive circle, while usually they would be collected in an earlier stage, to be eaten. A confiscated farm is therefore able to spread in the environment millions of seeds, paradoxically self-fulfilling the xenophobe prophecy of the foreign invasion declined in botanic terms. Beside this, such varieties are perfectly legal in Italy.

My impression is that these campaigns are driven by demagogic tactics, to achieve political consensus. The message is “we keep the decency of our territory”, to quote a local magazine. It is a racist message, within a racist set of mind. The outcome of this attitude is an attempt to froze the vital forces of human societies, and more specifically the becoming both of agriculture and food, which is also a way to deny Italian history. A little anecdote to make this more clear: the bean “Fagiolo Fico di Gallicano” is now a pillar of the food industry in the area of Lucca. But this beans variety was informally introduced in Italy by a migrant, returning back home from the Americas: he crossed the borders with few seeds hidden in his hat.

I love how, during your talk at HKW in Berlin two years ago, you talked about the fact that climate change had made us foreigners in our own house and how we might need to rely more on knowledge coming from the other side of the world than we’d like to admit. Could you develop on that? What can these “foreign farmers” you met in Prato, Palermo, Piedmont and elsewhere teach us?

Climate mutations have turned all of us into sort of foreigners, whether we stayed home or fled. What I learned from the farmers is that we need new types knowledge to be created with the scattered fragment of others’ experience. In Palermo, my garden suffered an unusual humid and cold springtime and a tropical storm at the end of the Summer, also unseen. For the pergola to survive, including the eradication of diseases without using chemicals, I had to combine information from different backgrounds, as if every traditional set of knowledge taken separately was not able to “solve” this type of vegetal entanglement. Each plant embodied a different degree of adaptation to a new environment, which was meanwhile undergoing a process of mutation: some seeds that I planted in the botanic garden of Palermo had arrived in Tuscany in 2005 from the rural areas near Wenzhou; a Senegalese hibiscus had been growing near Venice for 5 years, while bottle gourds from Bangladesh had already made Sicily their home, interweaving their vines with the local cucuzza, landed from Africa a long time ago.

There were no landlords in my shelter, and there was no room nor logic to deploy a useless dominant knowledge.

Leone Contini, Confiscated Chinese farm in Tuscany, Springtime 2020

Leone Contini, Confiscated Chinese farm in Tuscany, Springtime 2020

I’d like to come back to the Chinese communities in Prato for a moment because I suspect they’ve been terribly hit by the coronavirus crisis. From what i could read in local news, they quarantined very early and counted very very few cases of COVID19 but I suspect that many people in Prato might have resented their presence and held them responsible for the pandemic. Do you know something about how things are going for the community over there? Are they resorting to farming like they did during the financial crisis of 2008?

At the beginning of the epidemic populist propaganda blamed the Chinese community in Prato, spreading the fear of a potential COVID outbreak in the city. Very soon, however, it appeared that the infection in Prato was lower than the average numbers in Tuscany, and this narration was defused. A surreal if not ridiculous event was reported by local news a few days before the lockdown: the local police was preventing the quarantine of Chinese people who had returned home from China, blaming that this behaviour was “not regular”.

To answer your second question, the way COVID has transformed this local system of production would deserve a proper survey. I can only answer about a specific farm, near my house, which was confiscated in January and totally abandoned during the lockdown. I was there a few days ago: what was a flourishing family-based enterprise and a site of food production is now a neglected space. I walked across overgrown vegetation and destroyed greenhouses like in a post human scenario, until I met an old Chinese man, collecting the native plants, unknown to me, which had taken the place of the Chinese vegetables. Then I saw another man, bent under the weight of bag full of herbs. In the COVID aftermath the farmers turned into foragers, out of necessity, in order to eat. The general impoverishment has hit the community violently, especially the elders, especially in this rural context. I was admiring their strength and capability to put in place strategies and unexpected knowledge about the native flora, but I was also sad.

What have you been working on recently? And where can we learn more about what you’re up to?

I was always interested in our relation, as humans, with the wild flora. But during the lockdown this topic became central, since I started sourcing my daily food in the nearby forest (and just a few days ago I realised that, during these harsh months, my Chinese neighbours were doing the same). I would never have suspected the presence of such an amount of food in the radius of 500 meters around my home; moreover the herbs that I was able to recognise are just a fraction of the edible ones, since apparently the Chinese are collecting varieties not used in the local tradition. Unlike the seeds of a domesticated variety, which can cross the borders out of the human agency, the wild flora often travel despite the humans, or at least despite their intentions, proving that migration is an primal pattern of life.

Last summer I developed a project in a village near Matera, in the region of Basilicata (southern Italy). The village was founded centuries ago by refugees that fled the West Balkans: their descendants preserved their culture and language through many generations, until today. My project focused on the local wild flora, entirely named in an ancient Albanian dialect. Also here, like for the Chinese in Tuscany, the native-migrant-plants reconnect a scattered community with their home, by revealing that home is everywhere.

Thanks Leone!

Related stories: The Seed Journey to preserve plant genetic diversity. An interview with Amy Franceschini, Vegetation as a Political Agent, The ‘farmification’ of a joystick factory, The Manifesto for Rural Futurism, Super Meal, etc.