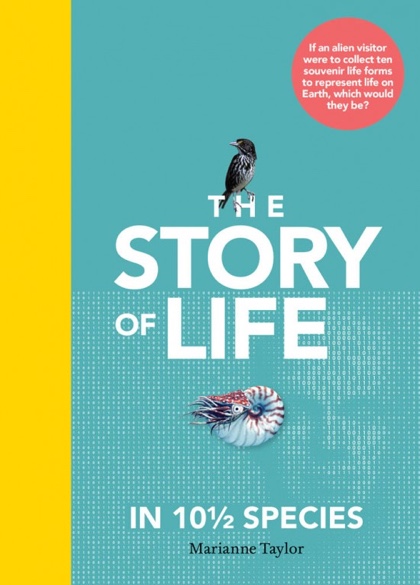

The Story of Life in 10 1/2 Species, by author, illustrator and photographer Marianne Taylor, must be the most interesting, beautifully designed and enlightening book about biology I’ve ever read. Packed with colourful illustrations, graphics and photos, it is also firmly rooted in rigorous science and doesn’t shun complexity.

The Story of Life in 10 1/2 Species, by author, illustrator and photographer Marianne Taylor, must be the most interesting, beautifully designed and enlightening book about biology I’ve ever read. Packed with colourful illustrations, graphics and photos, it is also firmly rooted in rigorous science and doesn’t shun complexity.

The premise of the book is surprising: “If an alien visitor were to collect ten souvenir life forms to represent life on earth, which would they be?” Taylor uses soft-shelled turtle, Darwin’s finches, the giraffe and other living organisms as a springboard to survey the long evolution of life on Earth and break down the intricacies -and in some cases the subjectivity- of taxonomy.

The fern, for example, opens up observations about the formation of oxygen in the atmosphere, about chlorophyll and the fact that “before there was life there was chemistry.”

Nautiluses have changed very little over the past 500 million years. Taylor explains how these “living fossils” survived 5 catastrophic mass extinctions. And yet, today they need to be protected from human activities. Already threatened by pollution and climate change, the molluscs are also hunted for sale as live animals or for their shells.

Act Wild for Lord Howe Island Stick Insects

The chapter about humans is a humbling one. It comes after the chapter on sponges, animals that have no organs, no circulation, no digestive systems, no distinct body parts. The human species has all of the above, plus an impressive list of evils: it is hyper-predatory, obsessed with domestication and it thrives at the expense of all other living things. The section also rehabilitates Neanderthal men. They were great apes too and were as quick-thinking and as societally advanced as we are today.

The chapter on the stick insect of Lord Howe Island does restore a tiny bit of faith in humanity. The story of the massive insect offers lessons about Lazarus species (organisms thought extinct and rediscovered), life in ultra hostile environments and the phenomena of island gigantism and island dwarfism but it also shows that many surviving species are dependant on human conservation efforts. If we disappear the least adaptable will fall into the “evolutionary dead-en” category.

The giraffe (Latin name: Camelopardalis!) tells about the inbreeding depression. A low population is accompanied by a drop in genetic diversity which can concentrate harmful genetic mutations that further weakens the population as a whole and slows down its potential rate of evolution.

Roelant Savery, Edward’s Dodo, 1626

The author uses the dusky seaside sparrow and the many, unsuccessful programs put in place to save it from extinction, as an opportunity to look at cloning technologies, genetic engineering and other tools at the disposal of conservationists to “rebuild” a species that is extinct or about to be extinct.

The “half” species in the title is artificial intelligence. That section is a bit of an odd one. It crams together the “artificial selection” imposed on cultivated crops and domesticated animals, genetic engineering, cybernetics, the marriage of living tissue to non-living components, etc. Its conclusion suggests a planet in the throes of mass extinction and powered by flying robot pollinators and artificial photosynthesis. Nothing to be cheerful about but Taylor keeps such a good balance between reasons to despair and reasons to keep the hope alive that I almost forgot to be angry about what we’re doing to the other inhabitants of planet Earth.