Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology. Shaping Our Genetic Futures, edited by scholar, curator and poet Hannah Star Rogers.

Publisher The University of North Carolina Press writes: Evolution has gotten us this far. Design may take it from here.

Aimed at raising awareness about genetic engineering, biotechnologies, and their consequences through the lens of art and design, Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology: Shaping Our Genetic Futures is an art-science exhibition curated by Hannah Star Rogers and organized by the NC State University Libraries and the Genetic Engineering and Society Center and shown at the Gregg Museum of Art & Design, in the physical and digital display spaces of the Libraries and on the grounds of the North Carolina Museum of Art.

By combining science and art and design, artists offer new insights about genetic engineering by bringing it out of the lab and into public places to challenge viewers’ understandings about the human condition, the material of our bodies and the consequences of biotechnology.

The book is available as a free PDF so i’ll keep this review extra short.

The artists selected for Art’s Work in the Age of Biotechnology investigate genetic engineering technology, a discipline that often comes with the alarming reputation of “playing God with life”. The artworks, however, are grounded in both laboratory research and every day concerns (food safety, animal exploitation, gender borders, etc.) This combination of the mundane and the scientific reveals the possible ethical and cultural dimensions of the so-called genetic revolution. It might make for disquieting encounters sometimes but it also enables readers to understand that their genetic futures are not solely in the hands of forbidding people in white coats, they are still up for debate.

The catalogue contains the usual mix of artwork presentations and essays by experts of various disciplines. I was particularly fascinated by biologists Megan Serr and John Godwin’s account on an hypothetical use of a genetic contraception that would cause rodent populations to decrease on island where their massive presence threaten biodiversity. As for the artworks, they do trigger all kinds of questions, curiosity and concerns. Here’s my short list:

Charlotte Jarvis, In Posse (Extracting plasma from my blood for making semen.) Photo Credit: Miha Godec

Charlotte Jarvis, In Posse (Female semen half way through being made and fresh out the fridge.) Photo Credit: Miha Godec

Charlotte Jarvis, In Posse: Making ‘Female’ Sperm (Alternate Realties Summit)

Charlotte Jarvis has been busy collaborating with Prof Susana Chuva de Sousal Lopes and Kapelica Gallery / Kersnikova Institute to create female sperm from the stem cells of her blood and skin.

Ciara Redmond, We Make Our Own Luck Here, 2018-ongoing

We Make Our Own Luck Here explores the ways in which culture and biotechnology interact using the famous symbol for luck. Using traditional selective breeding methods, the artist have created white clover plants with high numbers of four-leaf clovers. “By exploring and modifying the genetics of a plant to create a ‘lucky’ specimen we can play with the ideas of fate and destiny, whether they be genetic or supernatural.”

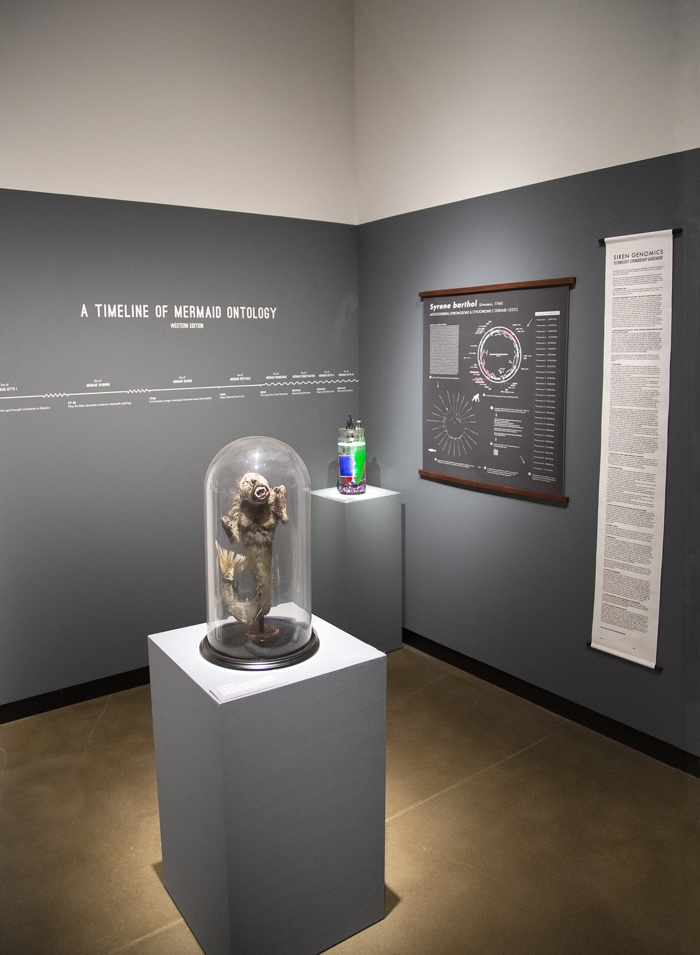

Richard Pell, The Mermaid De-Extinction Project

The Mermaid De-Extinction Project explores the possibility of giving life to a creatures we’ve dreamed about and written about for hundreds, even thousands of years. However, instead of creating a mermaid, the project aims at creates DNA that genetically resembles a mermaid. The work explores the tensions and debates raised by the many research projects around de-extinction and the kind of cultural beliefs and priorities that motivates them.

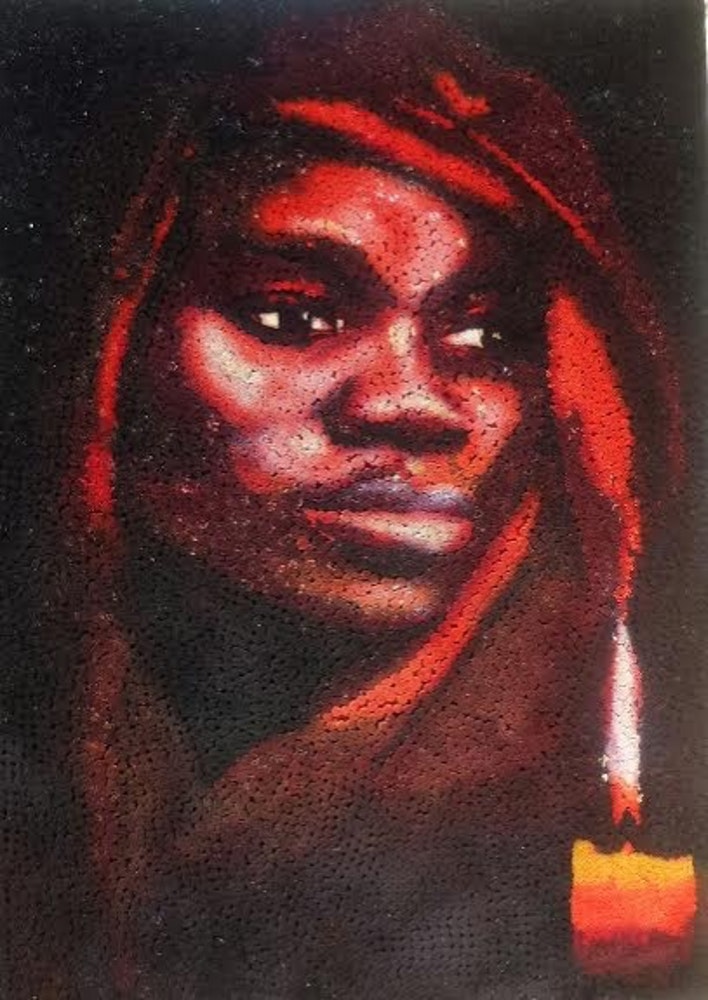

Emeka Ikebude, Fragments

Emeka Ikebude collected used toothpicks from mainly restaurants and dyed them with organic dyes.

The toothpicks retain human DNAs and microbiomes from the saliva, blood and food particles. Each of these tiny pieces of wood, alive with microbial forms, stands for a different human being. Combined together, the toothpicks depict a young man, an individual that came into being through the alliance of many living, anonymous and invisible entities.

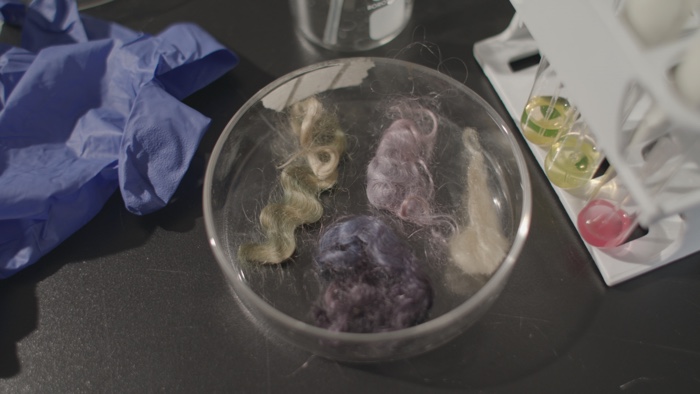

Diana Eusebio, Erin Kirchner, Grace Kwon, Rachel Rusk, Sydney Sieh-Takata, Kerasynth, 2018, synthetic fiber prototype garment

Diana Eusebio, Erin Kirchner, Grace Kwon, Rachel Rusk, Sydney Sieh-Takata, Kerasynth, 2018, synthetic fiber prototype garment

Diana Eusebio, Erin Kirchner, Grace Kwon, Rachel Rusk, Sydney Sieh-Takata, Kerasynth, 2018, synthetic fiber prototype garment

Kerasynth is a synthetically grown biological material that could replace all keratin-based animal fibres, eliminating thus the direct use of animals in the textile industry. It would be lab-grown but vegan and biodegradable. The team used tissue engineering to grow Hair Follicle Germ cells on devices that provide the cells with nutrients and remove waste, maintaining the integrity of the fiber without the animal’s direct involvement.

Joe Davis, Lucky Mice, 2019

Lucky Mice explore the possible correlations of serendipity and genetics through the creation of a mouse-operated dice-throwing apparatus and in vivo selective breeding of “lucky mice.” Mice that have the best outcome are selected and bred together (without any use of performance-enhancing drugs or genetic modifications.) The work not only comments on the use of live mice in art and science but also questions modern understandings of genetics and heritability.

Paul Vanouse (with Solon Morse, scientific collaborator), The America Project, 2016

The America Project is centred around the so-called DNA Fingerprinting, a process which Paul Vanouse appropriated to produce images of power—such as a crown, warplanes, a flag, etc. The DNA used is the one that visitors literally spit in a spittoon (glad to learn that such thing exists!)

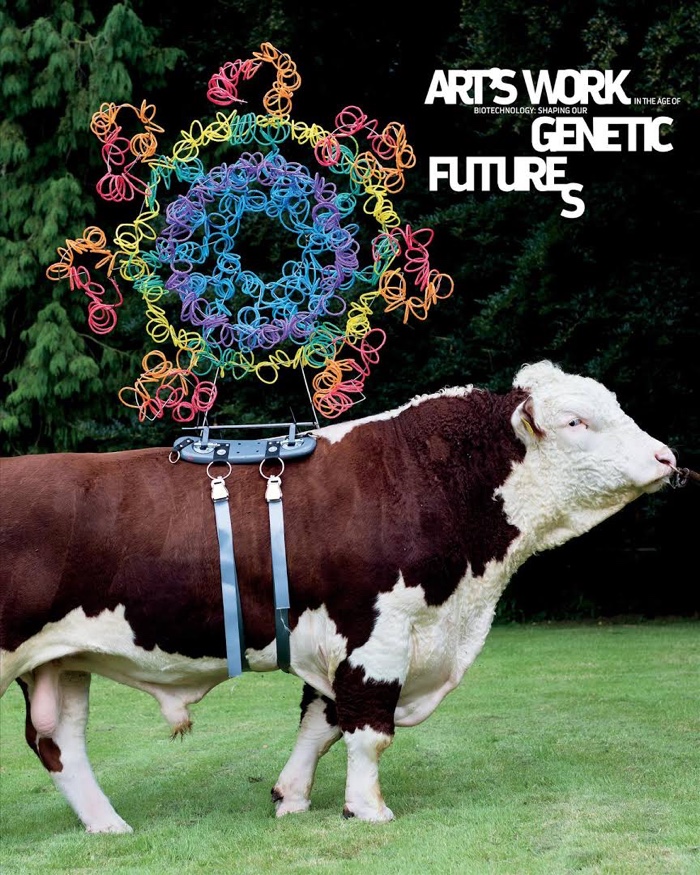

Maria McKinney, Management Polled, Doon just the job, 2016. From the series Sire

Maria McKinney, Environmental Footprint/Cornucopia, Bivouac (CH221). From the series Sire

The colourful sculptures on the back of the pedigree bulls above are made from semen straws. These plastic straws are storage receptacles used in the process of artificially inseminating cows. They come in a variety of colours to help distinguish between different bull’s semen while being stored in liquid nitrogen.

Each straw sculpture has been specifically crafted by artist Maria McKinney for the animal whose genetic signature it denotes.

McKinney‘s project Sire (a “sire” is a bull used specifically for breeding purposes) investigates genetics in cattle breeding. Through these sculptures and their photographic documentation, the artist not only explores the past and future of humanity’s efforts to shape nature but she also reveals the hidden systems behind beef and milk production.

Edward Steichen with delphiniums (c. 1938), Umpawaug House (Redding, Connecticut). Photo by Dana Steichen. Edward Steichen Archive, VII. The Museum of Modern Art Archives

I’ll add one artwork that i discovered in one of curator Hannah Star Rogers‘ short but incredibly informative essays about the relationship between art and biotechnology over time. In the text, she explains how she regards Edward Steichen as being a pioneer of art and genetics. A curator, painter and photographer, Steichen was also a keen breeder of delphinium, experimenting on the mutation in the plants to create new varieties. In 1936, the plants were the subject of the first flower exhibition ever held at MOMA.

Related stories: Tomorrow’s tailor-made cows, Proceed at Your Own Risk. Tales of dystopian food & health industries, etc.