If you ever find yourself in Milan this Winter. do head to the PAC, the Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea. Not only is it located next to what is probably the most hideous Christmas village in the entire universe but the art center also hosts an incredibly interesting exhibition about contemporary art from Argentina called Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day. The title of the exhibition is borrowed from Ce que la nuit raconte au jour (What the Night Tells the Day) , a novel by Argentine-born French author Héctor Bianciotti (1930 – 2012.) What the Night Tells the Day evokes the tensions between the obscure and the bright, between a country made of light and talents and a history that went through very dark episodes. The show explores some of the contrasts of Argentina by looking into its environmental struggles, relationship with religions, social inequalities, rurality, stories hidden under the official narratives, etc. There’s violence, beauty and you can’t help wondering how much Javier Milei’s will add to those layers of hope and suffering.

I liked the exhibition so much, i’ll visit it again in the coming weeks. Some highlights:

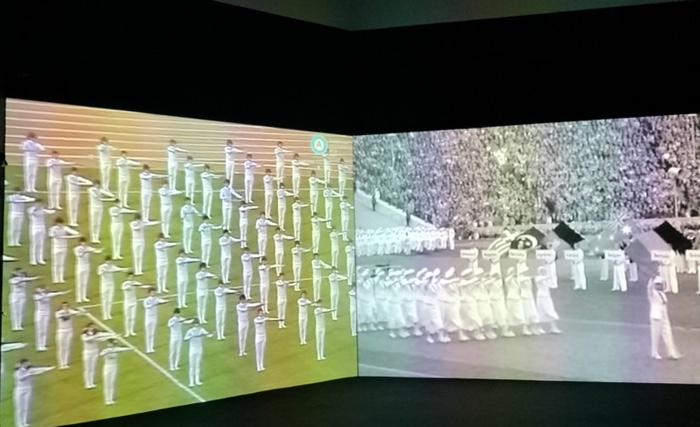

Adriana Bustos, Ceremonia Nacional, 2016

Adriana Bustos, Ceremonia Nacional, 2016. Installation view at PAC Milano

The video installation Ceremonia nacional (National Ceremony) shows side by side two key moments of fascist propaganda: an excerpt of the opening ceremony of the 1978 FIFA World Cup and an excerpt from Olympia, the documentary directed by Leni Riefensthal to glorify the Olympic Games held in Berlin in 1936. On the right side, black and white images bring us back to the political context of Nazi Germany. On the left side, Jorge Rafael Videla, the head of the military dictatorship that ruled Argentina from 1976 to 1983, presides over the ceremony.

Both sports events were marred by controversies and were used by the authoritarian governments as opportunities for nationalistic propaganda.

The juxtaposition highlights the models of fascist propaganda in the 20th century and the similarities between their formal and aesthetic structures. This non-linear vision of history takes an added chilling dimension in the light of Javier Milei’s downplay of some of the horrors that characterised Argentina’s military dictatorship.

Tomás Saraceno, exhibition view. Photo: PAC Milano

Tomás Saraceno, Fly with Pacha to the Aerocene, 2017-2023. Photo: Studio Tomas Saraceno

Tomás Saraceno, Fly with Pacha to the Aerocene, 2017-2023. Photo: Studio Tomas Saraceno

Over the past two decades, Tomás Saraceno has been engineering an “aerosolar” transportation system that would make flying sustainable and carbon-free. In January 2020, the artist’s Aerocene broke world records when pilot Leticia Noemi Marqués flew the black balloon above the white surface of the Salinas for 16 minutes. On the side of the balloon was a message that said, “Water and life are worth more than lithium,” in reference to the region’s environmental struggles.

Salinas Grandes is a large salt flat in central and northern Argentina that has been inhabited by indigenous communities for hundreds of years. Their lifestyles and livelihoods are now threatened by massive lithium extraction projects. With the arrival of mining companies in 2010, the communities –who make their living by herding animals, growing small crops, extracting salt and engaging in activities related to tourism– saw their historical rights over the use of salt imperiled. They united to protest and protect their territory.

Saraceno’s film Fly with Pacha to the Aerocene gives a voice to members of these communities but also to environmental lawyers and academics who ally with local populations and look for legal, academic and artistic strategies to achieve ecological and social justice.

The film is a compelling one. The story is a blueprint for the many examples of greedy, short-term exploitation of natural resources around the world. The ideas shared by the protagonists interviewed for the film, however, are not so well-known. They deserve to be spread widely. Sociologist Maristella Svampa, for example, criticizes the current model of the energy transition. Its conditions dictated by the North, the model ensures that richer countries benefit from green technologies while the most environmentally and socially damaging externalities are outsourced to countries in the South—especially Indigenous and rural communities. It is the usual colonial, extractivist method, only repackaged and meticulously greenwashed.

Far from being a litany of recriminations, the film calls for an intercultural conversation around energy transition that would include all concerned parties, including and especially the ones who don’t customarily have a say.

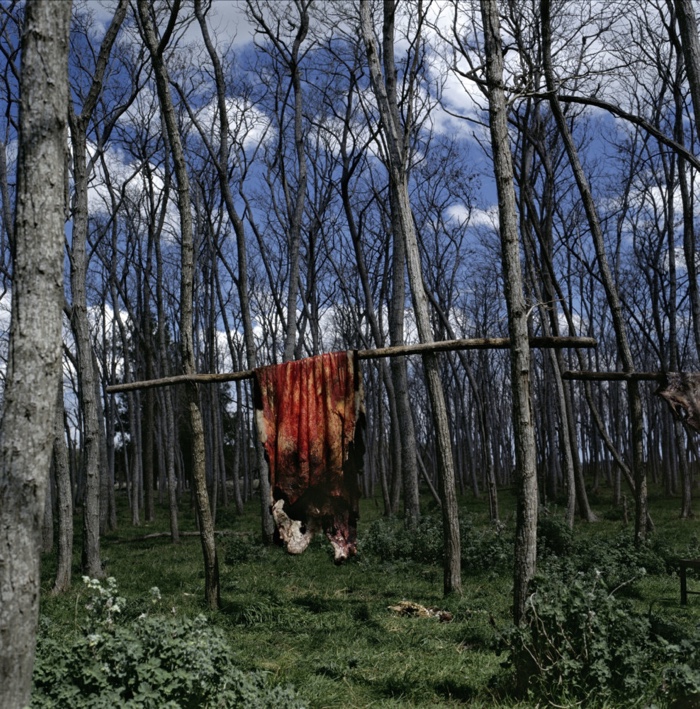

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day, exhibition view. Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Alessandra Sanguinetti, Untitled from the series En el sexto día / On the Sixth Day, 1996-2004

Alessandra Sanguinetti’s On the Sixth Day photo series captures the intimate but often very brutal relationships that humans weave with farm animals.

The images were taken on a farm outside Buenos Aires between 1996 and 2004. They show that, in contrast to industrialised farming where access to activities is severely restricted, the presence of death is there for all to see on small plots of land. Her photos make you realise that there’s only a thin line that separates the cute sentient being from that piece of flesh on your plate.

Even though the photographs are often violent, they also suggest that their author retains a deep sense of empathy for the animals and a deep respect for rural life.

I could barely look at some of the images in the gallery and i couldn’t get myself to publish some of them on this post. In an interview, Alessandra Sanguinetti explained how the public reacted to the first exhibition of these images: “The exhibition provoked rejection, or a lot of interest. There were people who asked me, a little anxious, why there was so much blood, so much cruelty. I’m surprised by this question because violence is all around us. Let me give you a very clear example: of all the images that could have been chosen of Jesus Christ, we went for the one of the cross, where he is bleeding. That’s the one everyone has above their bed.

Other people saw this work as a metaphor for human relationships. I liked that, because the concept of the work remains open. This is not a condemnation of the slaughter of animals or anything like that. I don’t want to give any answers to anything. In reality, I’m asking myself questions all the time.”

Adrián Villar Rojas, Untitled IV (From the series Rinascimento). Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Adrián Villar Rojas, Untitled IV (From the series Rinascimento), 2015-2021 Installation view al Hiding in Plain Sight, Pace Gallery, New York, 2021. Photo: Kyle Knodell

Adrián Villar Rojas created a still life inside the freezer compartment of a fridge. A kind of memento mori for a society that depends on technology, the composition remains fresh and edible thanks to the cold but, over time, it will eventually mutate and rot.

Graciela Sacco, Bocanada Composition

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day, exhibition view. Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Graciela Sacco’s Bocanadas occupy the balcony of the exhibition space. The series reproduces close-ups of mouths wide open. The repetition of these anonymous mouths evokes protests, hunger or calls for social change in Argentina and elsewhere.

The first Bocanada intervention took place in Rosario, Argentina, in 1993 when Sacco posted her images around the kitchen that prepared meals for local public schools. The kitchen staff was striking at the time and the movement affected the most underprivileged children for whom the school meals was often the only one they would get that day.

The artist later posted the images illegally on buildings, walls and palisades in Buenos Aires, Sao Paulo, New York, etc. Interfering with public space, the images short-circuit the messages of advertising and political campaign posters and bring attention to specific socioeconomic and political problems.

Leon Ferrari, La civilización occidental y cristiana / Western and Christian Civilization, 1965 Courtesy Colección Familia Ferrari, Acuerdo FALFAA – CELS Colección Familia Ferrari. Photo: Ramiro Larrain

Leon Ferrari’s “Western and Christian Civilization” is a near life-size Christ hanging crucified on a U.S. fighter jet hung nose-down, as if it were in free fall. The protest piece targets not only the Vietnam War and Western imperialism but also the abidingly Catholic culture of Argentina and its complicity with an increasingly repressive military regime.

In 2004, the piece was shown as part of a survey of the artist’s career in Buenos Aires. On that occasion, the local Archbishop, Jorge Mario Bergoglio —-now Pope Francis-— described it as “blasphemy” and “an embarrassment.”

More images from the exhibition:

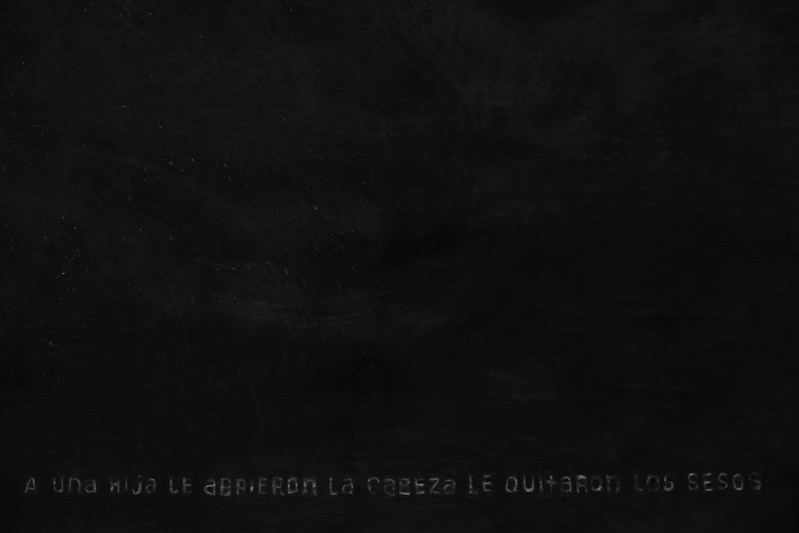

Ana Gallardo, Dibujos textuales, 2018

Mariana Bellotto, Trilogía pandémica

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day, exhibition view. Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Cristina Piffer, Doscientos pesos fuertes, dalla serie Las marcas del dinero, 2011. Installation view al MALBA – Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day, exhibition view. Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Miguel Rothschild, Atrapasueños IV, 2014. Courtesy Kuckei+Kuckei, Berlin /Palma

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day, exhibition view. Photo: Nico Covre – Vulcano Agency

Argentina. What the Night Tells the Day was curated by Andrés Duprat and Diego Sileo. The show remains open at PAC, Padiglione d’Art Contemporanea in Milan until 11.02.2024.