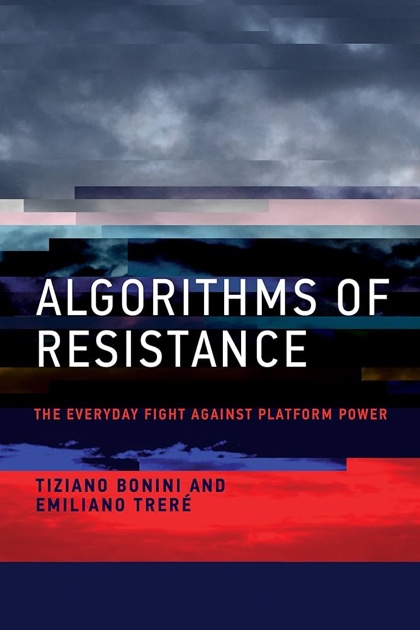

Algorithms of Resistance. The Everyday Fight against Platform Power, by Tiziano Bonini, associate professor of Sociology of Culture and Communication at Università di Siena, and Emiliano Treré, Reader in Data Agency and Media Ecologies at Cardiff University and Codirector of the Data Justice Lab. The book is published by MIT Press and available in Open Access and in paperback.

Algorithms of Resistance. The Everyday Fight against Platform Power, by Tiziano Bonini, associate professor of Sociology of Culture and Communication at Università di Siena, and Emiliano Treré, Reader in Data Agency and Media Ecologies at Cardiff University and Codirector of the Data Justice Lab. The book is published by MIT Press and available in Open Access and in paperback.

Countless essays detail how algorithms discriminate, exploit and oppress. Fewer investigate how users appropriate and subvert algorithms for their own benefit. Drawing on their own fieldwork and interviews with workers and on case studies from Europe, Latin America, the US, North Africa and Asia, Tiziano Bonini and Emiliano Treré analyse the many tactics that ordinary people develop to evade (even if only temporarily) the constraints of algorithmic power and pursue their own political, economic, cultural or social agendas.

Algorithms of Resistance focuses on three categories of platform defiers: gig workers (in particular food delivery workers), consumers and creators of cultural content, and political activists.

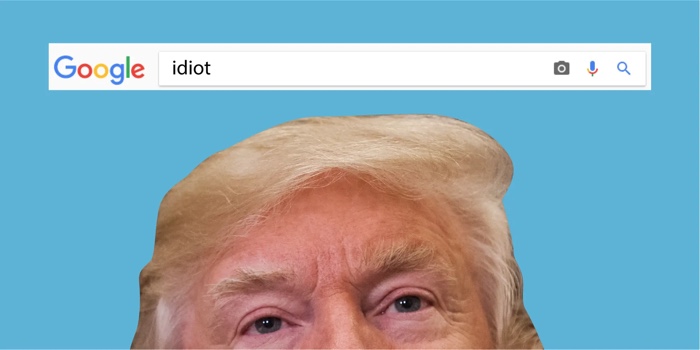

Protesters are gaming Google’s algorithm so photos of Trump come up when you search ‘idiot’. Photo: Zach Gibson/Getty; Shayanne Gal/Business Insider

Casa del Rider in Naples. Photo

In the chapter dedicated to delivery workers, Treré and Bonini show how drivers explore loopholes and cheat their algorithmic bosses in an attempt to regain some agency, improve working conditions, organise forms of collective action and build solidarity bonds. Their practices of everyday microresistance can be put to the service of different intentions, some of which are not necessarily positive or morally acceptable to the majority. More often than not, however, couriers have developed practices of cooperation and solidarity that challenge the neoliberal logic and competitive behaviour encoded in algorithms. The forms of mutualism not afforded by the apps range from online private chat groups where workers exchange information, coordinate collective actions and provide mutual support to platform cooperativism which emerged a few years ago as an alternative to commercial platforms.

I Made My Shed the Top Rated Restaurant On TripAdvisor. Photo by Theo McInnes

In the field of cultural industries, the most valuable currency is visibility. The section about cultural content creators focuses on Instagram “engagement groups”, or pods, where users attempt to artificially gain visibility by exchanging “likes”, comments and other forms of engagement with each other’s content. Some content creators even manage to secure greater agency by joining an independent union. The YouTubers Union (YTU), for example, was founded in 2018 to improve the working conditions of YouTubers. A year later, it teamed up with IG Metall, the largest trade union in Europe.

While digital visibility is paramount in the cultural industry, it is a double-edged sword for political activists. Visibility can mean recognition and greater capacity to tell your stories, but it also involves increased surveillance and control. In the chapter looking at algorithmic politics, Bonini and Treré study how both institutional and civil society actors appropriate and act upon algorithms in an attempt to reach their political objectives. The authors made an important point when they mentioned the importance of looking at the workforce behind digital propaganda and manipulation, not as brainless paid trolls, but as precarious, underpaid workers who are part of their domestic media industries.

Johanna Burai, World White Web, 2015

Simon Weckert, Google Maps Hacks, 2020

There are many reasons why i would recommend this book. The first is its nuanced and honest analysis of the power struggle between apps and their users. As the authors explain, having less power than digital platforms does not automatically mean being one of the “good guys.” Couriers and influencers, for example, can devise new hacks that benefit them alone, at the expense of others. And the same algorithms used by Black Lives Matter and other organisations to advance their socio-political causes can also be appropriated by racist, homophobic and misogynistic movements, or by authoritarian regimes.

I also appreciated the cautious optimism that the authors express regarding the possible emergence of a platform working class. While they welcome these acts of microresistance and place them within the long history of workers’ protests, Treré and Bonini also note that they only represent the first step in a process of awareness-raising among a multitude of actors whose position is subordinate to the power of platforms.

According to the authors of the book, as long as the people who use these platforms every day to work, consume, communicate, inform themselves and engage in political activity do not realise the full extent of data extractivism, their agency will remain severely restricted.

Related stories: Augmented Exploitation. AI, Automation and workers who fight back, More than a Glitch. Confronting Race, Gender and Ability Bias in Tech, On the obsolescence of cognitive and creative labour, Race After Technology. Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, Training Humans. How machines see and judge us, etc.