Few art spaces critically and rigorously examine the climate crisis, extractivism and social injustice without leaving you emotionally drained for weeks. Only one comes to mind at the moment: Zone2Source, a “testing ground for art & ecology” located right in the middle of Amstelpark, a 30 minute ride from Amsterdam Central by public transport.

Thomas Thwaites, The Harmless Car

Elena Khurtova Soil Works

Too often, cultural events examining environmental concerns tend to be bleak and frustrating. Zone2Source, however, strikes a rare balance: it is thought-provoking yet uplifting, critical yet imaginative. Spread across pavilions, artist gardens and outdoor spaces, it invites artists and the public alike to reimagine the evolving relationship between nature and culture. Over the years, they have looked at issues as diverse as the role of sound in our understanding of landscapes, extractivism, gardening as artistic practice, molehills, tree protests, the hidden afterlives of plastic waste, a Travel Agency for internal experiential trips to the Earth, the portrayal of the colonised landscape, the importance of soil, ethnobotany, etc.

In this interview, I catch up with Alice Smits, curator, art historian and the initiator and artistic director of Zone2Source. In the conversation, she tells me about the early days of the project, its guiding ethos and the challenges of running a cultural space where animals and plants are active participants. I also got Smits to tell me about Zone2Source’s new adventure: ZOÖP Amstelpark. A ZOÖP is form of organisation that fosters the cooperation between human and nonhuman life and ensures that the interests of all forms of life are taken into account. The question at the heart of the Zoöp model is, “Can democracy be expanded to a system where not only the voices of people are heard, but also those of trees, animals, fungi and billions of other life forms?”

Robbert van der Horst, Universe

Hi Alice! How did you get to create to Zone2Source? How did the whole adventure in the Amstel Park begin?

I started Zone2Source as a curatorial research project around ecological enquiries in what I would like to call a site-responsive (rather than site-specific) space. In 2013, I was coming back to the Netherlands after living abroad for many years and I started wondering, “What should I do with my life now?” Around that time, I was invited with my music group Oorbeek to the Glazen Huis in the Amstelpark. I got to know it really well. A few weeks later, I saw a call in the local newspaper in which the municipality was looking for cultural proposals for three pavilions in the Amstelpark. The history of the park sparked my proposal for what is now Zone2Source, a testing ground for art and ecology.

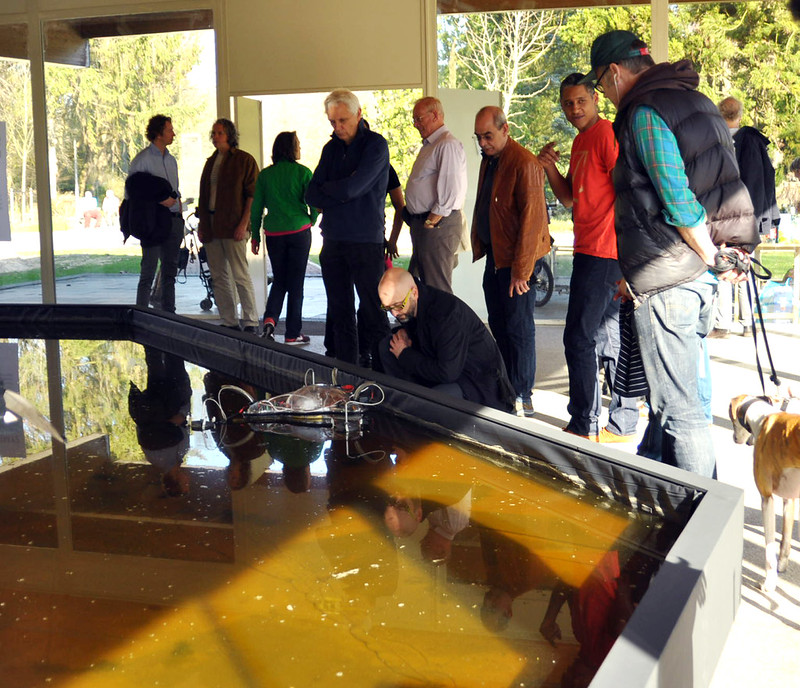

Jos Volkers, Bioremediating Missile

Špela Petrič, Fabulative Expeditions

Where were you before your return to the Netherlands?

First, I was in New York for five years to work on a PhD proposal but ended up curating art exhibitions, which I have continued to do to this day, but always with an interest to combine theory and practice. Then I came back for a couple of years in Amsterdam, curating for an art space. After that, I spent nine years in Uganda, although I was still going back and forth, co-directing the Amakula Kampala International Film Festival. The festival focused on African and world cinema with many local cultural projects relating film to music, theatres, arts, storytelling and we ran a mobile cinema project around the region. If you’re in Africa, you’re far away from the European art scene, so when I came back to Amsterdam with two little children, I was wondering what my next move would be.

The Amstel Park was specifically designed in 1972 for the Floriade horticulture exhibition. It was conceived following a typical World Expo model of bringing together flora and fauna from all over the world in one place. Although a lot has changed in the meantime, many of the flora and typical cultural artefacts have remained. There’s still a Japanese garden, a Belgian cloister garden, the rhododendron valley, the native gardens, the shape gardens, etc. Within this typical modern and colonial space of a world exhibition, we are collaborating with artists to develop projects that challenge the ideas and paradigms presented at the 1972 World Expo. Our goal is to reimagine the relationship between nature and culture, offering new narratives, imaginations and connections through artistic research methods and art projects. We offer the park to artists as a kind of “living lab”, using our three glass pavilions, two artist gardens and the outdoors of the park for exhibitions, Park Studios, workshops, excursions, debates, etc.

1972 was actually a very interesting year! It was the year of the Club of Rome’s report, The Limits to Growth, and of Should Trees Have Standing by Christopher Stone. It marked the beginning of the international environmental movement. We’re using this narrative as well. This was the year when everything could and should have changed. For the first time, people around the world truly understood the limits of our planet and recognised the need for a new political direction. Yet, we failed to act. Even during the Floriade, critics pointed out that the event did not reflect the growing environmental awareness of the time. All of this makes Amstelpark an interesting space to develop this project.

For me, curating has always been about doing research and combining theory and practice. My work focuses on how we can turn theory into transformative action, the dynamic space between acting and thinking. With Zone2Source, I am not only interested in presenting artworks, but, as you could say, in putting art to work. I am interested in the foregrounding of artistic research and how to connect people to the methods and questions -often embodied and situated – which artists employ to reshape our role in ecosystems.

I often challenge artists to not just show the results of their research but to make the research part of the exhibition. I think that, as a format, the exhibition is a stage and not an end to the research in which the artwork is making encounters in the world. It can change in the course of time. I have always found artists to respond very positively to this proposal. They appreciate the space they are given for experiments and audience engagement. For me, the urgency of art-science in the field of ecology does not lie in the academisation of artistic research but in taking art out of studios and labs as an engaged public practice of collective meaning-making. How can we create public research communities that are artist-led? This is what we are trying to develop with Zone2Source in the Amstelpark.

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay, Polyphonic Landscapes. Image courtesy Zone2Source

Budhaditya Chattopadhyay, Polyphonic Landscapes. Image courtesy Zone2Source

What strikes me about Zone2Source is that it’s not an easy space to work with compared to a traditional gallery spaces. You have artworks in the park outside, where they are exposed to the elements, to different temperatures, to wildlife, to plants growing where you’re not expecting them to grow, etc. How do you deal with all these variabilities? Can you even control anything?

We do not control the park at all. We are located inside an urban park that is governed by the municipality of Amsterdam. We organise many events in the park, such as workshops, excursions, performances, sound walks that do not need actual material intervention in the park. But we’re not allowed to place anything in the park unless we go through permission procedures.

We use the space as if it were a living lab that we offer to artists to create a different narrative and imaginary around it. While working outdoors presents its share of challenges, embracing the unpredictable is central to the shift we aim to create. This situation brings about interesting questions. For example, in the Polyphonic Landscapes research programme, together with four artists, we explored questions such as, “How can we conceive sound art outside of the more controlled context of a museum?” “How do we create a soundscape that establishes a dialogue with what we hear outside?” You accept that things will slowly deteriorate when they are outside or that we depend on the availability of sun energy. This acceptance, this willingness to let things evolve and change, is at the heart of ecological thinking.

Of course, we have the pavilions, but even our main indoor exhibition space the Glass House exists within glass structures, not traditional white-walled galleries. This transparency creates a constant dialogue with the outside, making the surrounding park an integral part of the experience. Often our exhibitions establish not only visible but also material links to the outdoors.

Then there’s The Orangerie, our functioning greenhouse. When the potted plants are moved outside between mid-May and October, we use the space as a Park Studio where artists develop artistic research projects in direct connection with the park, and visitors can interact with artists at work and in presentations, workshops and other events. In recent years, we have been given the maintenance over two enclosed gardens that we run together with two artist collectives and activate through workshops. Much of our programming and many of the artworks are outdoors, exposed to the wind, the rain, to people damaging things, etc. Outdoor art is definitely a challenge unto itself for a small organisation like ours. On the other hand, it is exactly this engagement with the park that is exciting.

Elmo Vermijs, Parliament of Trees at zone2source

I would also like to hear more about the Zoöp in Amstel Park. I first heard about the concept of a Zoöp three or four years ago when the Dutch pavilion of the Triennale in Milan presented it. I immediately thought that the Zoöp idea was really fascinating. But because I discovered it in an art and design context, I assumed it was purely speculative. Brilliant but never meant to actually materialise. On the other hand, I realised that the proponents of the Zoöp were very, very serious. What was your experience with it? How did you implement Zoöp in the park?

We’re just at the beginning, with many experiences and adventures still ahead. The Zoöp organisation, originally developed by Klaas Kuitenbrouwer at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, is now independent and growing into a movement. Several Zoöps already exist, and any type of organisation can adopt their model. While cultural institutions and regenerative farms were the first to join, potentially even supermarkets or hospitals can become Zoöps.

I’ve known Klaas Kuitenbrouwer for many years, and we’ve had conversations about Zoöp for some time. This isn’t just theory or speculation. The model was developed in collaboration with lawyers and other experts to create a practical framework for organising ourselves differently, placing the interests of all species instead of humans alone at the heart of every decision.

I have been considering the idea of transforming Zone2Source into a Zoöp for some time. But since we operate in a public space that we have no control over, the question that really interests me is, “What kind of responsibility and ethics can we, as citizens of this planet, bring to the stewardship of public space?” Maybe it’s the activist part of me but I thought, “If we become a Zoöp, then I want to see if I can encourage or challenge the city of Amsterdam to govern the Amstelpark as a Zoöp together with us and with other partners.” That was the start of a long trajectory.

We have been working on becoming a testing site for art and ecology since 2013, with a particular focus on bridging our art-science projects with policymaking. There is a lot of writing and talking about the role of artists in shifting imaginaries and narratives but in practice, their influence remains very marginal. Artists are usually invited to the table at the end of projects, rather than from the outset like any of the other experts.

By launching the first public Zoop, I want to explore the role of art and artistic research in cultural transformation. A compelling example is Elmo Vermijs’s Parliament of Trees, a very interesting art-science project where the artist worked with scientists from Wageningen University and involved two environmental lawyers. Our Park Studio was turned into a public dendrological lab exploring the life of the then 50-year-old trees of the Amstelpark. It culminated in a one-day speculative outdoor trial, Parliament of Trees, which looked at the possibility that trees, from their individual biographies, could act as witnesses of climate change. It’s where speculation can become a kind of prefigurative politics, rehearsing possible scenarios for the system change we need.

Together with artists, scientists and lawyers, we’re creating spaces to explore the kinds of laws and practices that can enable multispecies law and politics. These experiments sparked a public conversation to which we invited, amongst others, Rocco Piers, a politician from the municipality. We stayed in dialogue with him about how the Amstelpark – as a former Floriade site – could serve as a learning space for an eco-just city. While there was strong interest in our ideas, translating them into concrete action proved challenging. That’s when my discussions with Klaas led me to realise that the Zoöp model might offer the practical framework we needed. We held onto our original vision but adopted Zoöp’s methods and organisational structure to make it work. Instead of transforming Zone2Source into a Zoöp on our own, we chose to explore the potential of creating a public Zoöp—a collaborative effort with the city and other partners.

Klaas and I teamed up to advocate these ideas with the city. That’s when things really started to move. We organised a series of exploratory meetings with the municipality, bringing together politicians, civil servants and a wide range of interested organisations and individuals. These discussions culminated in an official initiative report that the municipality’s Department of Democratisation approved.

Which is interesting, because this isn’t just about being green or sustainable issues—it’s about radical democracy and species diversity in a city where all lives matter. Last year, Amsterdam marked its 750th anniversary, so we asked the municipality, “Can we govern Amsterdam in the next 750 years as a city for billions of lives rather than one million people?” “Can we use the Amstelpark as our testing site to experiment with citizens, civil servants, politicians and artists? What does this mean for politics, law, design, planning, etc.?”

The Zoöp model helped us get the city on board since Zoöps are already spreading across the country—it’s become a movement. The municipality agreed to a one-year experiment, and we launched Zoöp Amstelpark on October 4. The agreement was signed by Zone2Source and representatives of the city. They will evaluate it at the end of 2026 and, if deemed successful, the project will continue, which is our goal, but it will not stand or fall without the partnership of the municipality. We are framing this public Zoöp as a learning space where politicians, citizens and educational institutions can experiment together. In the meantime, the Amsterdam Sustainability Institute, a network platform from the Free University of Amsterdam and Yuverta, a vocational training school for applied biology and green cities, have joined Zoöp Amstelpark as well. Researchers and students in economics, life sciences and other fields are moving their research programmes to the Amstelpark, which is really exciting.

Since 2022, Zone2Source has been organising a School for MultiSpecies Knowledges, a programme we are now embedding within Zoöp Amstelpark. Our focus is on collective, engaged learning—moving beyond mere information transfer to develop a curriculum and artistic methods that foster transformative learning within the Zoöp. We are currently defining a few key themes for the first year; they bridge policymaking and maintenance of the park, research and public programming. It will be a huge challenge to bring together all the knowledge and ideas that will come out of this and connect the thinking and the acting.

I think the Zoöp is such a Dutch idea because it’s poetical, it’s a bit mad and it looks like it’s a completely impossible tas. But somehow the Zoöp team managed to ground it in reality and make it happen happen.

We’ve had an Party for the Animals for a very long time now! But I think the Zoöp can be seen as idealistic but also as very down-to-earth and realistic. We find ourselves in a very precarious situation where, as a species, we are destroying our own home. We even call that “pragmatic politics”! Finding ways to operate from an understanding of how we are dependent and entangled with all life is a very practical way to start learning how to become a positive species. The Zoöp is a bit different from the Rights of Nature movement. To me, Zoöp is a more urban form, centring on personal, ethical responsibility. It can be applied anywhere, even on a balcony in Shanghai. The Rights of Nature movement, on the other hand, often overlays Indigenous frameworks onto Western contexts, typically focusing on specific natural entities like rivers or mountains which come from close material and spiritual connections to these entities. This is not always the case in our societies. Besides, where does a river or a mountain end once we understand how everything is related to and affects everything else?

The Zoöp is more about learning and experimenting how we, as humans, can become a constructive species on this planet. It poses a fundamental question: “How can we represent the interests of all life and not just humans?” After all, laws already protect the interests of companies—so why not extend that principle to all living beings? It’s not as radical or speculative as it might sound. But how does it work in practice? Do other life forms need someone to advocate for their interests? In every Zoöp, there is a “speaker for the living”, a role dedicated to voicing the needs of non-human life.

Kevin van Braak, Kebun Sejarah / Garden of History. Performance at Zone2Source

BetweenTwoHands — Erin Tjin A Ton and Gosia Kaczmarek, Ecognosis

You mean that there’s one speaker for all the living? Or is there a different one for animals, another one for plants, one for fungi, something like that?

In the Zoöp model, there’s one speaker for the living that is representing the interests of all life forms within your organisation. Of course you cannot focus on everything so there are always choices made on what you engage with at a given moment.

At Zone2Source, as the first public Zoöp, we wanted to have a council for speakers of the living. We started with two people: Teun Karelse, who has been working with Zone2Source and the Zoöp for years, and Anne de Andrade who just started as a speaker and has more of a decolonial approach. As speakers, they will, for example, join municipality meetings to represent other life forms on issues of park maintenance. At some point, we might also get a young person and somebody from the neighbourhood involved in being a speaker for the living. There is a lot of talk of nature inclusivity, but to me, it is really about human inclusivity, in the sense of reintegrating Western humans – who have in the last centuries placed themselves outside nature – to play a more positive role in ecosystems. It’s not about becoming less human; it’s about becoming more human: engaging fully with your whole body, senses, mind and intellect. This isn’t about making sentimental gestures or romanticising nature. It’s about radical engagement with life, taking responsibility for every choice we make.

Circus Andersom, Travel agency Earth (Aarde Reisbureau)

When I listen to you or when I see what you’re doing, there is this hope that we, as human, there’s a way to inhabit this planet in a way that is more respectful and more compassionate towards other beings. How do you manage to stay so full of energy and life in the face of a world where so many things are going wrong? Trump, our obsession with profit and exploitation, the EU Green Deal taking a beating, deforestation, etc.

As an environmental activist, I often feel pessimistic too in the face of recent events and increasing apathy towards the ongoing environmental destruction. Yet, what keeps me going is hope: the knowledge that countless others are also working to build a different kind of world, even when despair feels overwhelming.

I’ve been active in recent years with Scientist Rebellion, a movement that often focuses on protesting against harmful systems. While resistance is crucial, activism isn’t just about opposition; it’s also about building spaces where we can collaborate and test new possibilities.

We must continue to fight against the fossil fuel industry, toxic multinationals and the politicians who enable them. We need to keep pushing, obstructing, and raising our voices. Sometimes, I’m frustrated that we no longer see the kind of mass mobilisation we had in the 80s—when I was 14, protesting against nuclear weapons with half a million people in the streets. I still believe that if we could overcome cynicism, we could unleash that same collective power again.

For me, starting a public Zoöp with the city of Amsterdam is another form of activism. We are creating spaces where we can experiment and practice how to build a society where the interests of all living beings are cared for. That is also the philosophy of the Zoöp: to start where you are, to challenge yourself, to unlearn old habits and change the way we do things. It’s a commitment to building not just human solidarity, but multispecies solidarity.

de Onkruidenier, The Shadow Garden

Sometimes i despair and then i remember that I’m lucky enough to spend time among people like you, people who have wonderful imaginations and are always trying to fight back. I also try to remember that most people are ready to make an effort to have a greener planet, to live more sustainably.

Like you, I draw a lot of energy from collaborating with like-minded people. Today, there are far more artists and individuals engaged with art and ecology than there were in 2013, when I started. Of course, artists and thinkers have been exploring these themes for decades, but back then, the mainstream approach was often limited to big blockbuster exhibitions about nature—showcasing 150 artists from around the world, with little regard for the environmental cost of shipping and production. Now, ecology has moved to the centre of artistic, institutional and curatorial practices. The shift has been profound.

Zone2Source also has two artists gardens now. Here we can really dig into the soil. I invited artist collectives (de Onkruidenier and The Center for Genomic Gastronomy) to collaborate on developing these gardens, which are inherently long-term projects. Gardens introduce a different rhythm to ecological thinking, one that unfolds over seasons and years. We also had Future Gardening, an exhibition that explored gardening as an artistic practice in reshaping our relations with the environment. It challenges us to rethink what an intervention or what co-creation looks like when you’re working within a garden shaped not just by human hands, but by countless other species as well. In this context, gardening becomes a dialogue, a way to question and reimagine our relationship with the living world and the role we play in it.

One of the gardens is by the Center for Genomic Gastronomy who uses it to look at the futures of food. Introducing food into an urban park represents a paradigm shift—moving beyond the traditional role of gardens as purely aesthetic spaces. Historically, gardens have been defined by their separation from farming, but this project challenges that notion. The second garden, by de Onkruidenier, has a more philosophical approach investigating, for example, speculative taxonomies: if we change the way we order and classify the world, how would that change the way we act in it? Both are exploring gardening as an artistic tool to reshape and explore our role in ecosystems.

For me, art is not just a conveyor of new narratives and new imaginations, it is also a method of embodied knowledge, of situated knowledge, an opportunity to experience differently together with people that can lead to transformative culture. We experience time and again that just knowing something does not lead to change. I am interested in building what you could call co-research communities around the practices and questions that artists are raising around ecological concerns, in which thinking and acting come together while engaging people in alternative practices.

Ivan Henriques, Symbiotic Machine. Photo courtesy Zone2Source

Sissel Marie Tonn, Sensory Carthgraphies

What is next for Zone2Source? Apart from continuing to work on the Zoop, what are the next exhibitions, or what are your plans for the immediate future?

One project that might be interesting to look at is the Multispecies Assembly, with Elmer Vermeijs whom I mentioned before. It is a very good example of how artistic or speculative projects can play a part in the Zoöp.

We held the first Assembly as part of the launch of Zoöp Amstelpark was built around a case brought in by a municipal gardener who posed a profound question, “Can a tree still be a tree?” It was a striking reflection from someone whose work often requires cutting down trees for public safety. But what does safety mean when we look at it from a more-than-human perspective? The Multispecies Assembly was built outdoors, using tree trunks provided by the municipality. The gathering brought together artists, neighbours, lawyers and politicians—each offering a unique perspective. The gardener’s question became a practical exercise, focusing on the everyday issue of park maintenance in the Amstelpark. But this time, we approached it from a multi-species viewpoint, considering not just human needs, but also the interests of the trees and all the life they support.

We are further working on a group exhibition this spring around the topic of invasive species and migration with four Asian artists based in the Netherlands, and in the summer we present two indoor and outdoor projects focusing on the entanglement of biological and digital networks. As part of the international Soil Assembly, we organise our 2nd Gardeners Assembly in our artists gardens and we are participating in a six-year research consortium dedicated to climate justice and artistic research. I am also reflecting on the organisation itself and how we can organise ourselves differently by bringing in artists as paid researchers of the park through longer term commitments. The ultimate vision is for Amstelpark to evolve into a learning space for artists and researchers, “What happens when you enter Zoöp Amstelpark?” “How do we make visible and experiential that you enter a park that doesn’t just serve people, but actively includes and advocates for the care and creativity of all forms of life?”

Thanks, Alice!

Zone2Source, Our Living Soil

Related stories: “Have we met?” A multispecies approach to the planet, Machine Wilderness: a world of ecological robotics, The Bioremediating Missile, Trust Me I’m an Artist. Ethics surrounding art & science collaborations (part 1) and (part 2).